21

IN THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA

(EASTERN CAPE DIVISION, GQEBERHA)

Case No.: 1922/2018

In the matter between:

SHERILLEE MORRIS Plaintiff

and

DR NICO VAN NIEKERK Defendant

JUDGMENT

ZIETSMAN AJ:

[1] On 28 May 2015 the defendant, a specialist surgeon, performed a laparoscopic repeat Nissen fundoplication1 on the plaintiff, causing a near fatal injury to her supra-hepatic inferior vena cava (“IVC”), and further complications. The plaintiff, Ms Morris, instituted an action in this court against the defendant for damages arising from the allegedly negligent conduct of the defendant, Doctor Nico van Niekerk

[2] The trial proceeded on the merits and quantum, but during the course of the trial the parties reached agreement on the quantum, subject to this court finding in favour of the plaintiff. The agreed amount is R2 160 548.00.

[3] The defendant admitted the contract as well as the duty of care which was in existence between the plaintiff and himself.

[4] The plaintiff pleaded various grounds of negligence in her particulars of claim.2 The plaintiff’s counsel,3 in their opening address and heads of argument, abridged the various grounds by explaining that the succinct issues to be determined are, whether the defendant was negligent:

“4.1. in not submitting the plaintiff to adequate preoperative conservative treatment, and in performing laparoscopic repeat Nissen fundoplication (“the redo surgery”) on the plaintiff in the absence of adequate proof that said conservative treatment had/would have failed;

4.2. in his planning and execution of the redo surgery;

4.3. in his treatment, planning and execution of the further surgery in respect of the plaintiff’s incarcerated hernia on 7 June 2015;

4.4. generally, with regard to his treatment of the plaintiff, by failing to act with such professional skill as is reasonable for a specialist surgeon;

and whether any of the above caused the plaintiff to suffer damages”.

[5] These four grounds involve an examination of the reasonableness of the clinical judgments made by the defendant. This exercise occurs in a mainly uncontested background, mostly because of the defendant’s admissions in his plea and also by reason of his failure to testify.4

[6] The factual context follows.

[7] It is common cause that during 2009 the defendant submitted the plaintiff for an endoscopy5. Considering the results of the endoscopy, the defendant performed a laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication procedure6 (“the primary procedure”) on the plaintiff.

[8] About three years later, in 2012, the plaintiff again consulted the defendant, complaining of heartburn. The defendant undertook another endoscopy, the result being that he observed grade A oesophagitis and a three centimetre recurrent hiatus hernia.

[9] Again three years later, on 12 May 2015, the plaintiff consulted the defendant with complaints of heartburn, reflux and nocturnal awakening. It is common cause that the defendant did not refer the plaintiff to a gastroenterologist after the consultation, for further investigations and a possible regime of conservative treatment such as proton pump inhibitors (“PPI”), and he also did not submit her for any other tests, such as an endoscopy, barium contrast study, a Barium meal 24 pH or any other motility studies,7 at any time, prior to taking the decision to perform the redo surgery on 28 May 2015.

[10] The defendant then, on 28 May 2015, without any of the mentioned further investigations being conducted, performed the redo surgery on the plaintiff, causing a near fatal injury to the plaintiff’s IVC, causing blood loss of approximately 1 300 millimetres. A cardio-thoracic surgeon was called to perform an emergency left-sided thoracotomy, failing which the plaintiff would have bled to death, due to the blood loss which caused her to be critically ill from hypovolemic shock.

[11] The plaintiff had to undergo further surgery to repair her incarcerated hiatus hernia on 7 June 2015, which surgery the defendant performed laparoscopically, as opposed to an open approach. During this surgery he caused a tear in the plaintiff’s stomach.

[12] The plaintiff suffered an ischaemic injury/bilateral watershed infarct as a result of excessive blood loss (haemorrhaging).

[13] The defendant, in his amended plea, admits that on 28 May 2015 he caused an injury to the plaintiff’s IVC, but denies that he was negligent in causing the injury. He also denies that his conduct fell short of the professional skill and care as is reasonable for a specialist general surgeon.8 The defendant also admits that he caused a tear in the plaintiff’s stomach during the surgery conducted on 7 June 2015, which occurred during the laparoscopic mobilisation of the stomach.9

[14] In addition to the above,10 the defendant admits that the plaintiff (on 28 May 2015) experienced sudden and severe bleeding into the thoracic cavity intra-operatively. He also admits that she was in need of a cardio-thoracic surgeon to perform a left sided thoracotomy to repair the injury to the IVC and that she lost approximately 1 300 millimetres of blood during the surgery. He further admits that the plaintiff required post-operative ventilation and was hospitalised in the Intensive Care Unit (“ICU”) of Netcare Greenacres Hospital from 28 May 2015 to 7 June 2015, required further blood transfusion, was critically ill from hypovolemic shock and had to undergo further surgery on or about 7 June 2015 as a result of herniation of her stomach into the left thoracic cavity. Also, he admits that following the last mentioned surgery, the plaintiff was again transferred to the ICU where she was put on full ventilation and intubation, and that she required further hospitalisation in the ICU from 7 June 2015 to 13 July 2015. She was transferred to the General Ward on 13 July 2015, and remained admitted there until 27 July 2015. The defendant however denies that all of the aforementioned were as a result of his breach of the contract with, or duty of care owed to, the plaintiff.

[15] The plaintiff adduced the evidence of Professor Sandie Rutherford Thomson, a specialist surgical gastroenterologist, and Doctor De Wit, a clinical neuropsychologist. The defendant adduced no evidence. I return to this later.

[16] Professor Thomson confirmed that he was reliant upon the defendant’s clinical notes, theatre notes and x-ray reports for his evidence and opinion. The correctness and the content of the aforementioned medical records were not placed in dispute.

[17] Professor Thomson testified that there was no indication in the defendant’s clinical note of 12 May 2015 that he placed the plaintiff on a course of PPI treatment prior to making a decision to perform the redo surgery. PPI usually presents a positive outcome for patients with reflux in which case they are not required to undergo surgery. In his opinion, the defendant should have referred the plaintiff to a gastroenterologist for a multidisciplinary treatment plan prior to considering revisional surgery. In his words, “gastroesophageal reflux disease is not life-threatening and there should never be a rush to embark on this type of revisional surgery”.11 Therefore, the redo surgery was performed prematurely and in the absence of the defendant, at least, instituting a proper trial of conservative medical treatment.12

[18] It is common cause that redo anti-reflux surgery is a complex operation.

[19] Professor Thomson testified that:

19.1. With regard to the planning of the redo surgery, he was adamant that the defendant should have referred the plaintiff for preoperative investigations such as an endoscopy and a barium contrast swallow prior to making the decision to perform the redo surgery. Not only does he consider these tests mandatory, but the various academic literature that he referred to also confirmed this to be the case. He went as far to state that these tests were the “absolute minimum” that one would do before revisional surgery.13

19.2. The defendant could not rely on the plaintiff’s endoscopy from 2012 to make the decision to perform the redo surgery, or to plan for it, in 2015.

19.3. In fact, in one of the articles provided by the defendant, the following is stated with regard to preoperative evaluation and investigations:14

“Patients who were candidates for reoperative antireflux surgery underwent a comprehensive evaluation, with a complete history and physical examination; investigations performed included barium esophagram, esophagogastroduodenoscopy,15 oesophageal manometry, pH testing, and gastric emptying studies”.

[20] Under cross examination, Professor Thomson confirmed that a medical practitioner needs contemporaneous investigations when the situation is dynamic. In casu, the plaintiff’s situation was dynamic, because she put on weight and the hernia could have become larger. Therefore, up to date information was necessary before proceeding with the operation.16

[21] It is common cause that the plaintiff did not receive any preoperative testing prior to the defendant taking the decision to perform the redo surgery on 28 May 2015.

[22] Despite it being common cause that the redo surgery is a complex operation, the defendant was the only surgeon in the theatre, assisted by one nurse and a general practitioner, the latter of which sole function was to operate the video camera. Professor Thomson has conducted similar surgery himself, which surgeries they always involved two specialists. Thus, there would be four individuals present during the redo surgery, being two specialist surgeons who have done this type of procedure before, or a surgical gastroenterologist and a camera man, a separate camera man and a scrub sister.17 There should also be a plan to convert from laparoscopic surgery to a thoracic open surgery should difficult adhesions be encountered.18

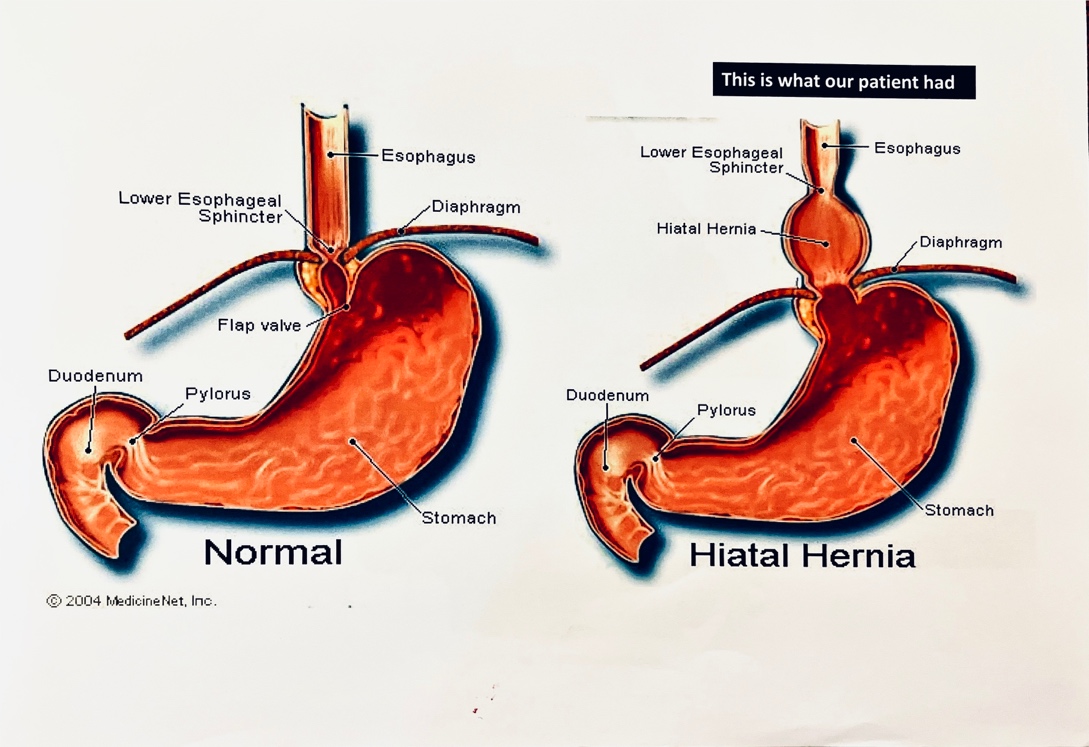

[23] Professor Thomson referred to some anatomy drawings. I find it apposite in the circumstances to include two of the drawings. He explained that the area where the injury occurred was just above the diaphragm, and, in order to explain the orientation, referred to the following drawing.

[24]

[25] The drawings above indicate where the hernia would have been prior to the primary operation. The aim of the primary operation was to put the hernia back into the abdomen and close any muscle defect. This is achieved by taking a piece of stomach, that is lying just under the diaphragm, and wrapping it around the piece of oesophagus, which is then moved into the abdomen. The result is to help stop the reflux of acid. That is what would have occurred in the 2009 operation.

[26] As stated by Professor Thomson, the same situation would pertain in 2015, except one would be unsure as to what exactly is in the chest, whether it is part of the stomach that has been wrapped around the oesophagus (also referred to as “the wrap”) or just the hernia itself. As I understood him, this uncertainty is one of the reasons why the planning of the redo surgery is so important.

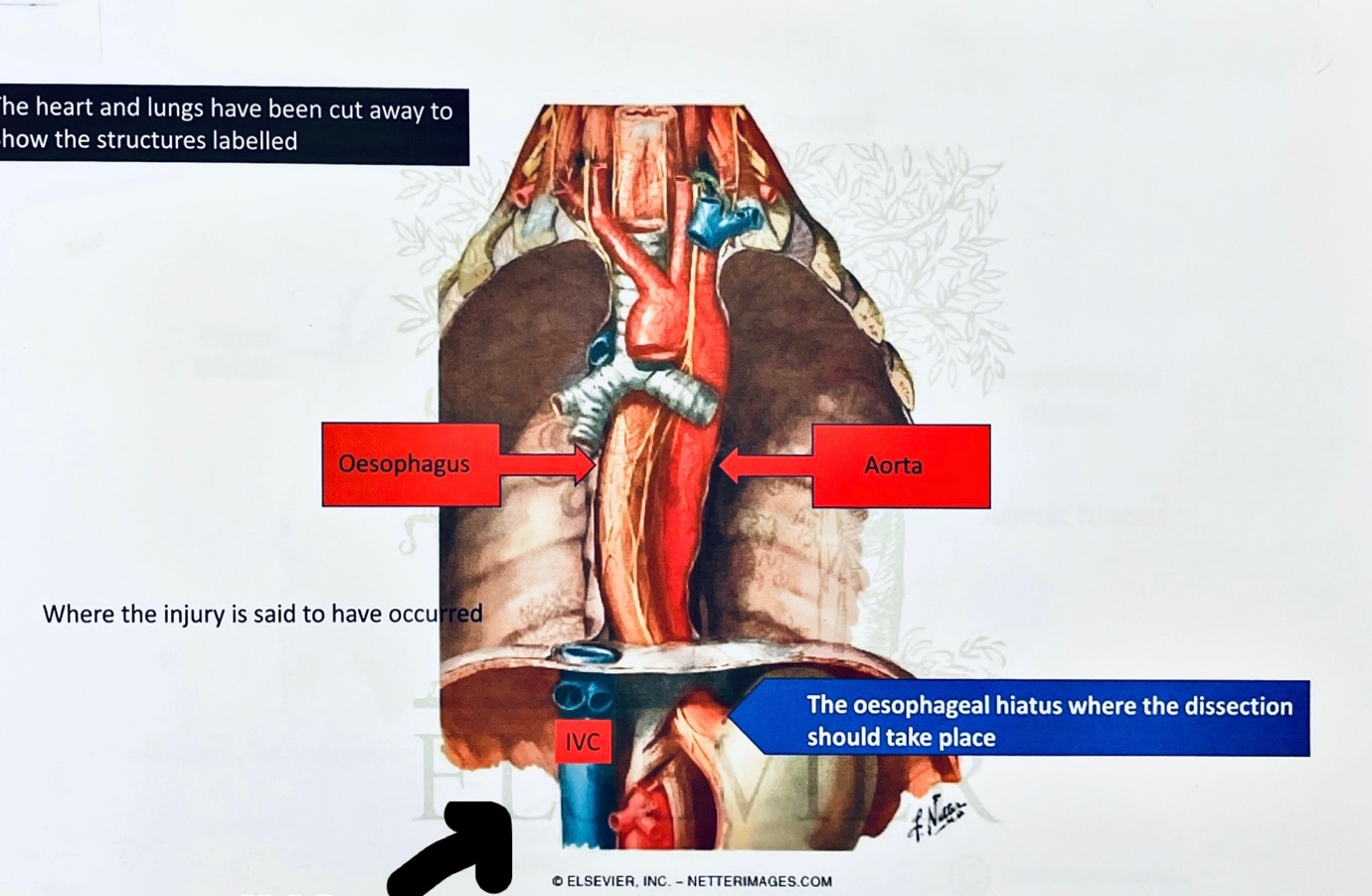

[27] This second drawing indicates where the injury is said to have occurred (the left side of the body is on the right in the drawing, and the right side on the left):

[28] In this drawing the heart and lungs have been excluded. The location of the IVC is evident from the drawing (also indicated with an arrow, which I inserted). It enters the diaphragm and then there is about 2 centimetres of it, a very short distance, before it enters the heart.

[29] Professor Thomson explained that in a primary procedure, a surgeon will start operating on the right hand side, but in a redo procedure a surgeon, knowing that the anatomy will be distorted on the right hand side as a result of the primary procedure, will start operating from the left hand side, to avoid the majority of distortions, before working his way across the right crura.19

[30] Professor Thomson explained how limited your peripheral vision would be through a laparoscopic camera, inserted into a person’s abdomen, by referring to the following analogy. When attending his daughter’s school concert and taking a video of her singing, in a group, his wife would prod him against his head and ask if he was certain that he is taking a video of their daughter. Since his view was focused through the lens, he realised that he should have been focusing somewhere else. That is what you want to avoid during an operation using a laparoscopic camera, the misconception that you might be looking at the right area, whereas you are not.

[31] Professor Thomson then explained that, whilst readily acknowledging throughout his evidence that he was obviously not present during the operation and emphasising that there is no operative note, for the defendant to have caused the injury to the IVC, presumably after he was through the crura and somewhere in the chest, the defendant must not have realised where he was. This is because, had he known, he would not have cut, or injured, the IVC.20

[32] I pause to mention that while injuries to the IVC are recognised complications, during primary and revision hernia surgery, it is, according to Professor Thomson’s uncontested evidence, extremely rare.21 Professor Thomson has not come across an injury to the IVC during his career.22

[33] After injuring the IVC, the defendant was required to enlist the assistance of a cardio-thoracic surgeon to perform an emergency left-sided thoracotomy, failing which the plaintiff would have succumbed by bleeding to death. During the time the defendant waited for the cardio-thoracic surgeon to repair the injury, the plaintiff lost a substantial amount of blood, approximately 1 300 millilitres, and was hypotensive. According to the defendant’s clinical notes, he was not in a position to control the bleeding and repair the plaintiff’s IVC. The reasons for that would be, according to Professor Thomson, that he was performing this complex redo surgery, without the assistance of another surgeon.23

[34] In his opinion, the fact that the site of the injury required a thoracotomy to stop the plaintiff from bleeding to death, suggests that the defendant had lost his way during the process of mobilising the recurrent hernia in the posterior mediastinum. Changes in the dimensions of the hernia and prior inflammation would be contributing factors to getting lost.

[35] According to Professor Thomson, the prior assessments would not necessarily have had any bearing on the actual injury as such, but it would have had a bearing on the planning and correct timing of the redo surgery.24 In his words: “The barium and to some extent possibly the gastroscopy, depending on how big the hernia looked in 2015, not in 2012, might have facilitated planning the operation. If the operation had been better planned the injury might not have occurred”.25 In other words, the planning might have helped to reduce the risk of the injury. And the defendant ought to have known this.

[36] Professor Thomson testified that it was obvious that complications might occur after the redo surgery, but more so in this instance because the intended procedure was not completed by the defendant since the procedure eventually became an emergency and they had to remove the laparoscopic equipment and prepare for the open operation. The hernia was still in the chest.26

[37] On 7 June 2015 the defendant, assisted by another general surgeon, conducted the repair of the plaintiff’s very current incarcerated hiatus hernia (the fundoplication). The defendant admits that he caused a tear in the plaintiff’s stomach during this surgery, which occurred during the laparoscopic mobilisation of the stomach. It is Professor Thomson’s opinion that this could in all probability have been avoided by a thoraco-abdominal approach, which would have allowed a better repair of the large hiatus defect.

[38] Professor Thomson reasoned that the further surgery on 7 June 2015 was unduly delayed. This is because there was undoubted evidence, having regard to the x-ray reports, of a septic source in the left chest already on 2 June 2015. This was most likely associated with a complication of the fundoplication and should have been investigated and explored earlier. The delay may have prolonged the ICU stay of the plaintiff considerably. Also, it is apparent from the records that the defendant was absent during the period 4 to 6 June 2015, which would have contributed to the delay in investigating the plaintiff’s condition, the drain in her chest was draining significant amounts of fluid, and delayed the re-intervention on 7 June 2015 to repair the hernia.

[39] Before I turn to the evidence of Doctor De Wit, I will refer to the plaintiff’s current neurological condition, which is common cause.

[40] The plaintiff’s current neurological condition is outlined in the admitted opinion and prognosis contained in the medico-legal report of Doctor Britz, neurologist.27

[41] The plaintiff’s neurological sequelae following the incident in May 2015 is summarised by Doctor Britz to be:

“Mild cognitive impairment – vascular type, with associated complaints of dysphasia and word selection anomia (word finding difficulty); mild dys-calculi; and a very severe post-traumatic stress disorder. The plaintiff’s neurological deficit is rather in keeping with the so-called watershed infarct (bilaterally) that occurred during the episode of hypotension (haemorrhaging). The neurological deficits (complaints of mild cognitive impairment and dysphasia) are most likely permanent in nature”.

[42] Doctor De Wit testified that the following primary diagnosis can be made on the plaintiff. Firstly, mild neurocognitive disorder due to possible brain injury as a result of possible prolonged sedation and/or oxygen deprivation following respiratory failure as a result of the complications of the procedure on 28 May 2015. Secondly, the plaintiff also qualified on the DSM-V28 for a diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder.29 The plaintiff’s persistent difficulties resulted in her being continuously retraumatised by her lack of ability to function at her pre-morbid levels.

[43] Doctor De Wit further testified that during her assessment of the plaintiff, it was apparent that the plaintiff struggled with word finding and often used tangential speech, requiring long explanations to describe basic concepts, and she used words interchangeably. Doctor de Wit explained that this is caused by damage to the area of the brain responsible for speech, causing extreme difficulty forming words and sentences. The condition is called Broca’s aphasia. The aphasia is exacerbated by anxiety.30 There is no treatment for this and it is a debilitating and devastating injury.31

[44] The plaintiff was easily overwhelmed and prone to anxious decompensation. On the Brief Psychiatric Inventory Test, the plaintiff scored a 6 for anxiety, which indicates that her anxiety is severe, (since a score of 7 is the highest and would indicate that a person should be institutionalised).32 As a result, Doctor De Wit diagnosed the plaintiff with chronic anxiety.

[45] Doctor De Wit concluded that, taking into account the plaintiff’s various diagnoses, she would not be able to give evidence. However, she conceded, when it was put to her in cross examination, that the plaintiff would be able to testify with accommodations. This was, unfortunately, not further explored. It is therefore not clear what these accommodations would entail.

[46] That concluded the evidence adduced on behalf of the plaintiff.

[47] In Member of the Executive Council for Health & Social Development, Gauteng v TM obo MM33 the court held that:

“[125] The cogency of an expert opinion depends on its consistency with proven facts and on the reasoning by which the conclusion is reached. In Coopers (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd v Deutsche Gesellschaft für Schädlingsbekämpfung MBH this Court held: ‘[A]n expert’s opinion represents his reasoned conclusion based on certain facts or data, which are either common cause, or established by his own evidence or that of some other competent witness. Except possibly where it is not controverted, an expert’s bald statement of his opinion is not of any real assistance. Proper evaluation of the opinion can only be undertaken if the process of reasoning which led to the conclusion, including the premises from which the reasoning proceeds, are disclosed by the expert.’” (My own emphasis).

[48] There is, in my view, no reason to doubt the veracity of the evidence of Professor Thomson and Doctor De Wit.

[49] The defendant adduced no evidence and closed his case. Although the defendant took the stand, the plaintiff’s counsel objected to the defendant giving expert testimony without having filed a notice and summary in terms of Uniform Rule 36(9)(a) and (b).

[50] In terms of rule 36(9)(a) and (b):

“(9) No person shall, save with the leave of the court or the consent of all parties to the suit, be entitled to call as a witness any person to give evidence as an expert upon any matter upon which the evidence of expert witnesses may be received unless—

(a) where the plaintiff intends to call an expert, the plaintiff shall not more than 30 days after the close of pleadings, or where the defendant intends to call the expert, the defendant shall not more than 60 days after the close of pleadings, have delivered notice of intention to call such expert; and

(b) in the case of the plaintiff not more than 90 days after the close of pleadings and in the case of the defendant not more than 120 days after the close of pleadings, such plaintiff or defendant shall have delivered a summary of the expert’s opinion and the reasons therefor”.

[51] It is trite that rule 36(9) is designed to avoid a litigant being taken by surprise in relation to matters in respect of which they would in the normal course of events be unable, before trial, to prepare their case effectively so as to meet that of their opponents.34

[52] The defendant’s counsel contends that “the defendant attempted to lead the evidence of Dr Van Niekerk, but was eventually precluded from doing so on the basis that an expert summary had not been filed on his behalf and that he was attempting to give evidence of an expert nature in that his testimony involved facts and knowledge which a lay person would not possess”.

[53] After the plaintiff’s counsel raised the objection to the defendant giving expert testimony, and having heard argument from the plaintiff and defendant’s counsel, I made the following ruling. That, if I were to find that the evidence constitutes expert evidence, or opinion evidence, I would have to exclude it. Accordingly, the defendant had to elect what he intended to do; proceed without having filed a summary, alternatively, he had to indicate whether he wanted to consider his position. I specifically stated that some of the defendant’s evidence, up to that stage, constituted expert testimony.

[54] The defendant’s counsel then requested that the defendant’s evidence be interposed by the evidence of his expert, Doctor Marais.

[55] I considered the request and referred the parties to the judgment of HAL obo MML v MEC for Health, Free State,35 where the court held as follows:

“[211] … Until the factual basis for the experts’ evidence had been established their opinions were inadmissible.

[214] There may be cases where it is permissible, or even necessary in order to set the scene for the court to appreciate the issues, for experts to give evidence at the outset of the proceedings when the factual evidence on which they base their opinions may still need to be led. That will ordinarily be so where the factual dispute is narrow and clear-cut and the expert can properly express an opinion on all relevant factual scenarios, without relying on disputed facts. This was not such a case and nor are most similar cases.

[215] Where the facts are central to the opinions of the experts, courts should require that those facts be led in evidence before the experts express their opinions. Primarily that is for the benefit of the court, which is thereby placed in a position where the expert’s opinion can be assessed, and, if need be, queried or elucidated, in the light of the factual material before it.”

[56] I therefore made a further ruling that since the factual basis for the expert’s evidence had not been established, in other words the defendant’s evidence, I would not be acceding to the request that the defendant’s evidence be interrupted by the evidence of Doctor Marais.

[57] The defendant’s counsel thereafter placed on record that the defendant, “under protest”, closes his case. It is not apparent, in the circumstances, what was meant by “under protest”. The word “under protest” is defined in the Oxford Dictionary as “unwillingly and after making protests”. Self-evidently, the defendant made the conscious and deliberate decision, in consultation with his experienced legal representatives, to close his case.

[58] I want to make it clear, the defendant was not precluded from adducing evidence. He was precluded from adducing expert evidence, without first complying with the provisions of rule 36(9). The plaintiff had already closed her case and the prejudice to her was obvious.

[59] This court is therefore faced with the scenario of an unconscious patient who has suffered an admitted injury, and further admitted complications. The spectre of negligence on the part of the defendant looms large.36 Still, the onus was on the plaintiff to prove her case on a balance of probabilities.

[60] The approach for establishing the existence or otherwise of negligence was formulated by Holmes JA in Kruger v Coetzee37 as follows: 38

“For the purposes of liability culpa arises if—

(a) a diligens paterfamilias in the position of the defendant—

(i) would foresee the reasonable possibility of his conduct injuring another in his

person or property and causing him patrimonial loss; and

(ii) would take reasonable steps to guard against such occurrence; and

(b) the defendant failed to take such steps.

. . .

Whether a diligens paterfamilias in the position of the person concerned would take any guarding steps at all and, if so, what steps would be reasonable, must always depend upon the particular circumstances of each case. No hard and fast basis can be laid down.”

[61] As alluded to above, although the onus was on the plaintiff to prove her case, the defendant had a duty to adduce evidence to combat the prima facie case made out by the plaintiff. The defendant had to advance an explanatory account of the injury on 28 May 2015, and the further complications thereafter. He failed to do so.39

[62] The conduct of the defendant is to be judged against the standard of the reasonable surgeon performing a repeat Nissen fundoplication, unfortunately, this court is unable to judge the defendant’s conduct, on his version, since he failed to testify.

[63] With regard to the defendant’s failure to testify, the following was said in Ex parte the Minister of Justice: In re Rex v Jacobson and Levy:40

“Prima facie evidence in its usual sense is used to mean prima facie proof of an issue, the burden of proving which is upon the party giving that evidence. In the absence of further evidence from the other side, the prima facie proof becomes conclusive proof and the party giving it discharges his onus.”

[64] In other words, prima facie proof is evidence calling for an answer.

[65] The defendant should have foreseen the possibility of his conduct, in proceeding with the redo surgery in the absence of the plaintiff having received preoperative conservative treatment and his failure to refer the plaintiff for preoperative investigations, resulting in injury to the plaintiff and causing her loss. He failed to take reasonable steps to guard against the rare complication of injuring the plaintiff’s IVC and causing further complications. The result of which was that the defendant had to enlist the assistance of another surgeon, a cardio-thoracic surgeon, which he should have done in the first place.

[66] It has been recognised that while the precise or exact manner in which the harm occurs need not be foreseeable, the general manner of its occurrence must indeed be reasonably foreseeable.41

[67] It is astonishing that the defendant decided to simply proceed with redo surgery in circumstances where the last endoscopy, done by him, was done three years prior. Also, knowing his anatomy, he ought to have known that the situation is dynamic and requires up to date information before proceeding with this complex surgery.

[68] With regard an inference of negligence, in Goliath v MEC for Health, Eastern Cape42 the court concluded as follows:

“[19] Thus at the close of Ms Goliath's case, after both she and Dr Muller had testified, there was sufficient evidence which gave rise to an inference of negligence on the part of one or more of the medical staff in the employ of the MEC who attended to her. In that regard it is important to bear in mind that in a civil case it is not necessary for a plaintiff to prove that the inference that she asks the court to draw is the only reasonable inference; it suffices for her to convince the court that the inference that she advocates is the most readily apparent and acceptable inference from a number of possible inferences (AA Onderlinge Assuransie-Assosiasie Bpk v De Beer 1982 (2) SA 603 (A); see also Cooper and Another NNO v Merchant Trade Finance Ltd 2000 (3) SA 1009 (SCA)). That being so, the MEC, in failing to adduce any evidence whatsoever, accordingly took the risk of a judgment being given against him. After all, it was open to the MEC to adduce evidence to show that while Ms Goliath was undergoing surgery, reasonable care had indeed been exercised by his employees. That he did not do.”

[69] Returning to the four summarised grounds of negligence advanced on behalf of the plaintiff, the evidence lends support to a finding that the defendant was negligent in not submitting the plaintiff to adequate preoperative conservative treatment, and in performing the redo surgery on the plaintiff in the absence of adequate proof that said conservative treatment had/would have failed.

[70] I also find that the defendant was negligent in his planning (or lack thereof) and execution of the redo surgery without the assistance of another specialist.

[71] On a conspectus of all the evidence presented, I find that the defendant was also negligent in his treatment, planning and execution of the further surgery in respect of the plaintiff’s incarcerated hernia on 7 June 2015.

[72] Causally, the defendant’s conduct caused the injuries and complications to the plaintiff whilst having regard to the boni mores, such action was clearly unlawful. The defendant failed to act with such professional skill as is reasonable for a specialist surgeon.

[73] The defendant criticised the plaintiff for not having testified. What would she have testified about? She was unconscious when the defendant operated on her and the facts are mostly common cause, and the quantum has been agreed upon.

[74] I therefore find that the defendant’s unlawful and negligent conduct caused the plaintiff damages, the amount which has already been agreed upon.

[75] With regard to costs, the merits involved complex and technical issues. By its very nature, the action involved specialist medical knowledge and expertise. The experts involved, by both parties, come to twenty three. I am therefore satisfied, on a consideration of the relevant factors, that the employment of two counsel by the plaintiff was justified in this case. There is also no reason why costs should not follow the result.

[76] One final comment, I would like to extend my gratitude to both the plaintiff and defendant’s counsel for their comprehensive sets of heads of argument.

[77] The following order is issued:43

77.1. the defendant shall pay to the plaintiff an amount of R2 160 548.00 as damages;

77.2. payment of the amount in paragraph 74.1 above shall be made directly to the plaintiff’s attorneys of record, Meyer Inc.’s trust account, the details of which are as follows:

Name: Meyer Inc.

Bank: Standard Bank

Branch: Port Elizabeth

Branch code: 050017

77.3. the defendant shall pay interest on the amount referred to in paragraph 1 above a tempore morae from date of judgment to date of final payment;

77.4. the defendant is to pay the plaintiff’s taxed, alternatively agreed costs of suit, such costs are to include:

77.4.1. the costs of the reports and supplementary reports, if any, of:

77.4.1.1. Dr M Locketz

77.4.1.2. Dr P Pretorius

77.4.1.3. Dr P Potgieter

77.4.1.4. Dr F Naude

77.4.1.5. Dr D Meintjies

77.4.1.6. Dr F Visser

77.4.1.7. Dr C Rossouw

77.4.1.8. Dr H Vawda

77.4.1.9. Dr Z Gani

77.4.1.10. Dr M Marais

77.4.1.11. Dr O Shenxane

77.4.1.12. Dr H Prinsloo

77.4.1.13. Dr RJ Keeley

77.4.1.14. Professor PC Bornman

77.4.1.15. Dr E de Wit

77.4.1.16. Ms A van Zyl

77.4.1.17. Mr D Pretorius

77.4.1.18. Arch Actuaries

77.4.1.19. Professor SR Thomson;

77.4.2. the qualifying and reservation fees and expenses, if any, of:

77.4.2.1. Dr M Locketz

77.4.2.2. Dr P Pretorius

77.4.2.3. Dr P Potgieter

77.4.2.4. Dr F Naude

77.4.2.5. Dr D Meintjies

77.4.2.6. Dr F Visser

77.4.2.7. Dr C Rossouw

77.4.2.8. Dr H Vawda

77.4.2.9. Dr Z Gani

77.4.2.10. Dr M Marais

77.4.2.11. Dr O Shenxane

77.4.2.12. Dr H Prinsloo

77.4.2.13. Dr RJ Keeley

77.4.2.14. Professor PC Bornman

77.4.2.15. Dr E de Wit

77.4.2.16. Ms A van Zyl

77.4.2.17. Mr D Pretorius

77.4.2.18. Arch Actuaries

77.4.2.19. Professor SR Thomson;

77.4.3. the testifying and attendance fees of:

77.4.3.1. Professor SR Thomson

77.4.3.2. Dr E de Wit;

77.4.7 the costs of the employment of two counsel, where so employed;

77.5. the defendant is to pay interest on the plaintiff’s taxed or agreed costs at the prevailing prescribed interest rate per annum calculated from 14 (fourteen) days after allocator or, written agreement, to date of payment.

______________________

T. Zietsman

ACTING JUDGE OF THE HIGH COURT

Appearances:

For plaintiff: Adv. OH Ronaasen SC with adv. B Westerdale, instructed by Meyer Incorporated

For defendant: Adv. HB Ayerst instructed by BLC Attorneys

Dates heard: 15, 16, 17 and 18 March 2021, 6 and 8 June 2022, 31 October 2022 and 20 November 2022

Date delivered: 25 April 2023

1 Wrapping the top part the stomach around the oesophagus and moving into the abdomen, sometimes known as a “wrap” – see record 15/03/2021 at p 86 lines 19 to 25 and p 87.

2 Particulars of claim (as amended) paras 7.1 to 7.15.

3 The plaintiff was represented by Senior and junior counsel.

4 This aspect will be more fully dealt with hereinafter.

5 Also referred to as a gastroscopy or oesophago-gastro-duodenoscopy (OGD), which is a procedure used to visually examine a person’s upper digestive system – record 15/03/2021 at p 42 lines 18 – 23.

6 Anti-reflux surgery.

7 Which includes: pH metrimetry (to confirm whether acid reflux was occurring) and manometry (to establish whether the patient has difficulty swallowing, which is called dysphagia) – see record 15/03/2021 at p 45 line 14 to p 46 line 16.

8 Particulars of claim para 7.12 read with the defendant’s plea para 17.1.

9 Particulars of claim para 7.14 read with the defendant’s plea para 19.

10 Particulars of claim paras 8 and 8.1 to 8.12 read with the defendant’s plea para 21.

11 Record 15/03/2021 at p 38 lines 16 to 25.

12 Record 15/03/2021 at p 38 lines 16 to 25 and p 116 lines 16 to 20.

13 Record 15/03/ 2021 at p 77 lines 23 to 25.

14 Exhibit A at p 144.

15 Another term for endoscopy.

16 Record 17/03/2021 at lines 21 to 25.

17 Record 15/03/2021 at p 80 line 24 to p 82 line 11; and p 101 lines 7 to 18.

18 Record 15/03/2021 at p 108 lines 11 to 25 and p 110 lines 8 to 12.

19 Two muscles which wrap around the oesophagus (which are, according to Professor Thomson, like reinforced muscle).

20 Record 15/03/2021 at p 96 line 23 and p 97 line 7.

21 Record 16/03/2021 at p 11 lines 16 to 17.

22 Record 18/03/2021 at p 13 lines 19 to 20. Professor Thomson qualified as a surgical gastroenterologist in 1999 and has been involved in the academia and public service ever since.

23 Record 15/03/2021 p 98 at lines 6 to 9, and p 99 lines 8 to 23.

24 Record 16/03/2021 at p 13 lines 15 – 18.

25 Record 16/03/2021 at p 14 lines 16 – 21.

26 Record 15/03/2021 at p120.

27 Exhibit G.

28 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th Edition (DSM 5) requires clinicians to list symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) according to five criteria and in terms of the presence or absence of symptoms.

29 Record 08/06/2022 p 18 lines 18 to 21 and p 19 lines 1 to 13.

30 Record 08/06/2022 p 6 lines 24 to 28, p 7 and p 8 lines 1 to 19.

31 Record 08/06/2022 p 53 lines 12 to 25; p 54 lines 1 to 9.

32 Record 08/06/2022 p 23 lines 13 to 24.

33 [2021] JOL 50880 (SCA) at para 125 (footnote omitted).

34 Erasmus Superior Court Practice at D1-486.

35 2022 (3) SA 574 (SCA).

36 As was the case in Myers v MEC Department of Health, Eastern Cape 2020 (3) SA 337 (SCA) at par 74.

37 1966 (2) SA 428 (A).

38 See also Oppelt v The Department of Health Western Cape 2016 (1) SA 325 (CC) at paras 69 to 74.

39 Meyers at par 74.

40 1931 AD 466 at 478.

41 Sea Harvest Corporation (Pty) Ltd and Another v Duncan Dock Cold Storage (Pty) Ltd and Another 2000 (1) SA 827 at paras 21 to 22.

42 2015 (2) SA 97 (SCA) at par 19.

43 Submissions were made on behalf of the plaintiff, that an order as set out herein should be made, which order is not unusual.