Taxonomies

- Collections > Environmental Law

- Case indexes > Environmental

- Case indexes > Environmental > Actors in environmental law

- Case indexes > Environmental > Actors in environmental law > Role of state in relation to environment

- Case indexes > Environmental > Criminal offences in environmental law > Criminal offences relating to the environment

- Case indexes > Environmental > Flora and fauna > Animal welfare and rights

- Case indexes > Environmental > Flora and fauna > Plants, forests and forestry (flora)

- Case summary

-

The application was brought by the first applicant, The Humane Society International – Africa Trust (“HSI-Africa”), dedicated to, inter alia, the protection of wild animals. The First Respondent is the Minister of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (“Minister”). The Minister is the National Management Authority responsible for the allocation of quotas in terms of the Regulations published under the National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act 10 of 2004 (“NEMBA”) in respect of The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (“CITES Regulations”), which Regulations were published in 2010.

The current position in South Africa is that the permissible hunting of black rhinoceros, leopard and elephant for trophy purposes is strictly controlled via a permit system. The Minister fixes the quotas for such hunting.

In October 2021, the Minister gave notice that she intended to consult on the 2021 quota for the export of hunting trophies of elephant, black rhinoceros and leopard. In February 2022, the Department issued a press release, announcing the Minister’s determination of the quotas for the year 2022.

HSI-Africa argued, in particular, that the Minister’s decision to roll over the 2021 decision to 2022 was not authorised under the CITES Regulations and thus unlawful.

HSI-Africa contended that the ultimate purpose of the review is to ensure that the Minister complied with her statutory functions under NEMBA. The interim interdict in turn would ensure that the publication of her decision is effected in line with the process, which it suggests is prescribed by the NEMBA. The Minister’s decision should thus be held in abeyance while the legality thereof is determined by the reviewing court.

In considering the application for an interdict, the court considered the criteria of irreparable harm and balance of convenience. It held that, should the interdict be granted, the lives of these animals who will be hunted, will be spared. It held that the irreparable harm is thus the difference between life and death. It further found that the balance of convenience also favoured the applicant.

The court ordered that the decision of the Minister to allocate a hunting and export quota for elephant, black rhinoceros and leopard for the year 2022 is interdicted from being implemented.

IN THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA

WESTERN CAPE DIVISION, CAPE TOWN

REPORTABLE

CASE NO: 6939/2022

In the matter between:

THE TRUSTEES FOR THE TIME BEING OF THE

HUMANE SOCIETY INTERNATIONAL – AFRICA TRUST First Applicant

BERNARD ORESTE UNTI N.O. Second Applicant

GEORGE THOMAS WAITE III N.O. Third Applicant

ANDREW NICHOLAS ROWAN N.O. Fourth Applicant

DONALD FRANK MOLTENO N.O. Fifth Applicant

CRISTOBEL BLOCK N.O. Sixth Applicant

ALEXANDRA GABRIELLE FREIDBERG N.O. Seventh Applicant

and

THE MINISTER OF FORESTRY, FISHERIES

AND THE ENVIRONMENT First Respondent

THE DEPARTMENT OF FORESTRY, FISHERIES

AND THE ENVIRONMENT Second Respondent

Bench: P.A.L. Gamble, J

Heard: 18 & 23 March 2022

Delivered: 21 April 2022

This judgment was handed down electronically by circulation to the parties' representatives via email and release to SAFLII. The date and time for hand-down is deemed to be 12h30 on 21 April 2022.

JUDGMENT

____________________________________________________________________

GAMBLE, J:

INTRODUCTION

-

This opposed application for an urgent interdict pending the review of a decision taken on 31 January 2022 by the first respondent (“the Minister”) to fix a quota for the number of leopard, elephant and black rhinoceros that may be lawfully hunted in the Republic of South Africa and later exported abroad as trophies by foreign hunters during 2022, was initially heard by this Court in the Fast Track of the Motion Court on 18 March 2022.

-

After further remote hearings of the matter on 23 and 25 March 2022, judgment was reserved with the Minister furnishing the Court with an undertaking that she would take no further steps to implement her decision pending the Court’s decision on the interdict pendent lite. Subsequent to those hearings the Minister filed an explanatory affidavit dated 28 March 2022 to which reference will be made later.

-

At those hearings the applicant was represented by Mr. L.J. Morison SC and Mr. B. Prinsloo, while the Minister was represented by Mr. S. Magardie. The Court is indebted to counsel for their helpful submissions (both written and oral) which have facilitated the delivery of this judgment. The court would also like to thank the Minister for delivering a detailed answering affidavit under significant time constraints.

THE PARTIES

-

The application was brought by the first applicant, The Humane Society International–Africa Trust (“HSI-Africa”), which is an international organization represented locally through a trust registered under the Trust Property Control Act, 57 of 1998, with the second to seventh applicants as its duly appointed trustees. It has its principal place of business within this Court’s jurisdiction in Mowbray, Cape Town.

-

The deponent to the founding affidavit, Mr. Anthony Gerrans, who is its executive director, informed the Court that –

“HSI-Africa is an organization dedicated to the protection of animals, the improvement of the conditions of farm animals, the protection of wildlife, the reduction of the use of animals in biomedical and cosmetic testing and the better protection of companion animals. HSI-Africa’s work ranges from education and training to political and legal advocacy within, inter alia, the Republic.”

As its name suggests, HSI-Africa is evidently the local chapter of an international body.

-

Further it is said by Mr. Gerrans that –

“HSI-Africa comprises of members who are animal protection advocates, academics and professionals, all of whom are concerned with all matters relating to the governance and regulation of biodiversity and wildlife. HSI-Africa has been campaigning for the enforcement of environmental and animal welfare laws, in line with a decade of precedent holding that animals are sentient beings capable of suffering and experiencing pain and deserving protection of their interests. HSI-Africa contends that animal welfare and the suffering of animals should in and of itself always be a factor to be considered when an act of public power is exercised which affects an animal.”

Mr. Gerrans relies on NSPCA1 for the latter submission

-

Citing s24 of the Constitution, 19962 it is further claimed that –

“The suffering of animals, the conditions under which animals are kept and the conservation of animals are all a matter of public concern and the respect for animals and the environment is a constitutional prerogative.”

-

With reference to the statutory process embarked upon by the Minister in this matter, purportedly exercising her powers under the National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act, 10 of 2004 (“NEMBA”), Mr. Gerrans points out that HSI-Africa –

“(H)as routinely been engaging in the consultative process for leopard hunting and export, elephant hunting and export and black rhino and export prior to 2022. Amongst other matters, HSI-Africa submitted substantive comments to the Minister on these issues in the years 2017, 2019 and 2021, and HSI-Africa submitted its comments on the draft Norms and Standards for Trophy Hunting of Leopards. HSI-Africa also sits on various Wildlife Consultative Forums.”

-

In the result, HSI-Africa’s locus standi to bring this application in its own interest, on behalf of its members and in the public interest under ss38(a),(d) and (e) of the Constitution3 is not in issue. Nor is its entitlement to seek to protect the environment and enforce the provisions of a specific environmental management act as contemplated under s32 of the National Environmental Management Act, 107 of 1998 (“NEMA”)4 disputed.

-

The Minister is cited in these proceedings in her official capacity as the member of Cabinet responsible for environmental affairs and, more particularly, as the so-called National Management Authority responsible for the allocation of quotas in terms of Reg 3(2)(k) of the Regulations published under NEMBA in respect of “The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora” (“CITES Regs”). These regulations were published on 5 October 2010 in Government Gazette 33002 under Government Notice R 173 and are of full force and effect. The Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (“the Department”) has been cited as the second respondent, seemingly for the sake of good order. No relief is sought against the Department herein.

UNDERSTANDING CITES

-

CITES is a multilateral international treaty which was adopted by 21 countries in Washington DC on 3 March 1973. It was ratified by South Africa thereafter and it entered into force on 13 October 1975. The overall purpose of CITES is to regulate the worldwide trade in endangered species of, inter alia, wild animals and plants.

-

As the Minister points out in her affidavit,

“25. Thousands of species of plants and animals are subject to CITES regulations, which are designed to protect endangered species of fauna and flora from over-exploitation by strictly regulating or prohibiting their international trade.

26. CITES works through the listing in Appendices of species of wild flora and fauna whose conservation status is threatened by international trade. The level of protection accorded to the species depends upon which Appendix of CITES it is listed. Once listed, imports and exports of the species concerned are subject to a permit system implemented by state management authorities.

27. CITES therefore depends for its implementation on a national working regulatory and permitting system and for its enforcement, on inter alia a working system of inspection and border controls to ensure that imports and exports of listed species only take place subject to the required permits.”

-

The purpose of the three categories of Appendices that form part of CITES is set out in the Fundamental Principles contained in Article II of the Convention.

“1. Appendix I shall include all specimens threatened with extinction which are or may be affected by trade. Trade in specimens of these species must be subject to particularly strict regulation in order not to endanger further their survival and must only be authorized in exceptional circumstances.

2. Appendix II shall include:

(a) all species which although not necessarily now threatened with extinction they become so unless trade in such specimens of such species is subject to strict regulation in order to avoid utilization incompatible with their survival; and

(b) other species which must be subject to regulation in order that trade in specimens of certain species referred to in sub-paragraph (a) of this paragraph may be brought under effective control.

3. Appendix III shall include all species which any Party identifies as being subject to regulation within its jurisdiction for the purpose of preventing or restricting exploitation, and as needing the co-operation of other Parties in the control of trade.

4. The Parties shall not allow trade in specimens of species included in Appendices I, II and III except in accordance with the provisions of the present Convention.”

Articles III, IV and V individually regulate the trade in the specimens of species included in the three categories of Appendices while Article VI deals the procurement of permits for authorised trade under CITES.

-

In terms of Article XI of CITES, the signatory parties meet from time to time in conference and take decisions which then become binding on such member states affected thereby, as the case may be. Such meetings are termed a “Conference of the Parties” (“COP”) and are referred to as such, usually with reference to the city where, and year when, it was held. The Minister explains the COP system further.

“28. COP is one of the main institutions established by CITES. The COP meets every two to three years to consider amendments to Appendices I and II of CITES, review progress in the conservation of listed species and to make recommendations for improving the effectiveness of the Convention. The provisions of CITES have to be read in the light of the interpretations and guidance set out in the resolutions adopted by the COP.”

-

Article IX of CITES (“Management and Scientific Authorities”) requires each participating state party to designate one or more management authorities with the competence to grant permits or certificates on behalf of that state and, further, to designate one or more scientific authority to perform the functions required by such body under CITES.

-

With the promulgation of the CITES Regs, the Minister of Environmental Affairs automatically became the National Management Authority contemplated under Reg 3, with the specific duties allocated to her in Regs 3(2) (a) to (k). These include, for instance, the duty –

“(a) to consider and grant permits and certificates in accordance with the provisions of CITES and to attach to any permit or certificate any condition that it may deem necessary…

(e) to coordinate national implementation and enforcement of the Convention and these Regulations and to co-operate with other relevant authorities in this regard;

(f) to consult with the Scientific Authority on the issuance and acceptance of CITES documents, the nature and level of trade in CITES-listed species, the setting and management of quotas, the registration of traders and production operations, the establishment of Rescue Centres and the preparation of proposals to amend the CITES Appendices…

(k) to coordinate requirements and allocate annual quotas to provinces.” (Emphasis added)

-

Under Reg 3(4) each of the nine provincial MEC’s in the relevant provincial department responsible for nature conservation constitutes the Provincial Management Authority for CITES, with similar powers as exercised by the National Management Authority but devolved in accordance with provincial requirements and obligations.

PROTECTED SPECIES AND “TOPS”

-

On 23 February 2007 in GNR 151 the erstwhile Minister of Environmental Affairs and Tourism gazetted regulations under NEMBA in which certain fauna and flora were listed in a schedule according to the categories “critically endangered”, “endangered”, “vulnerable” and “protected” species. In the schedule to those regulations,

(i) The Black Rhinoceros was listed as “endangered”, meaning that it was an “(i)ndigenous species facing a high risk of extinction in the wild in the near future, although (it) was not a critically endangered species”;

(ii) The Leopard was classified as “vulnerable” meaning an “(i)ndigenous species facing a high risk of extinction in the wild in the medium-term future, although (it) was not a critically endangered species or an endangered species”; and

(iii) The African Elephant was classified as “protected” meaning that it is an “(i)ndigenous species of high conservation value or national importance that requires national protection”.

-

On the same day, in GNR 152, the erstwhile Minister gazetted a second set of regulations under NEMBA, the “Threatened or Protected Species Regulations,” colloquially referred to by counsel as the “TOPS Regs”. These regulations were intended to address a wide range of issues relating to the protection of listed fauna and flora as contained in GNR 151, including the control of the captive breeding of wild animals, the issuing of a host of permits for the control of, inter alia, game farms and hunting associations, and the hunting and protection of the wild populations of the protected species listed in GNR 151. The TOPS Regs also proscribe a number of hunting methods of, inter alia, the said threatened and protected species.

-

The position then is that the permissible hunting of black rhinoceros, leopard and elephant for trophy purposes is strictly controlled within South Africa via a permit system. The Minister fixes the quotas for such hunting, while the MEC’s have the authority to issue individual permits. All such hunting must comply strictly with the hunting methods listed in the TOPS Regs.

THE CITES QUOTAS IN CASU

-

In addition to their local protection under NEMBA, all three of the aforementioned species are listed in Appendix I of CITES. The respective quotas for purposes of international trade in the trophies of such species after they have been hunted locally under the TOPS Regs are as follows.

LEOPARD (Panthera Pardus)

-

The leopard was included in the original CITES Appendix I of 1975. At COP 4 (Gaberone, 1983) member States adopted the first resolution to sanction trade in leopard skins. The Minister points out in her affidavit that this resolution recognized that the leopard was not endangered throughout its range and COP 4 thus considered it acceptable to establish export quotas and a tagging system for leopard skins from seven countries. From the outset, South Africa was allocated an annual quota of 150 leopard trophies under COP 4.

-

At COP 14 (The Hague, 2007) the attending states recognized that in some sub-Saharan countries the population of leopard was not endangered and accordingly recommended a review of the established quotas. South Africa’s leopard quota remained static at 150 animals per annum which, according to the Minister, is still the annual quota. I should point out that the leopard quota in several other African countries is significantly higher than that in South Africa. For example, the current annual leopard quotas in Ethiopia, Tanzania and Zimbabwe are each 500 animals, in Zambia it is 300 and Namibia it is 250. These quotas were confirmed at COP 16 (Bangkok, 2013).

-

The Minister annexed to her affidavit an extract from a resolution adopted at COP 10 (Harare, 1997) which is referenced “Conf.10.14 (Rev.CoP 16) Quotas for leopard hunting trophies and skins for personal use.” As I understand it, the annotation “Rev.CoP16” indicates that the issue was dealt with and revised accordingly at COP 16 in Bangkok.

-

In any event, the document referenced “Conf.10.14” concludes with the following recommendations by the COP of 1997 held in Harare.

“(I)n reviewing applications for permits to import whole skins or nearly whole skins of leopard (including hunting trophies), in accordance with paragraph 3 (a) of Article III, the Scientific Authority of the State of import approve permits if it is satisfied that the skins being considered are from one of the following States, which should not authorize the harvest for export of more of the said skins during any one calendar year (1 January to 31 December) than the number shown under ‘Quota’ opposite the name of the State, understanding that the skins may be exported in the year of harvest or in a subsequent year (for example, a country with a quota of 250 leopard skins for 2010 may authorize export of 50 leopard skins taken in 2010 during 2010, 150 of the leopard skins taken in 2010 may be exported during 2011, and 50 of the leopard skins taken in 2010 may be exported in 2012)…

In the table which follows that recommendation, South Africa’s quota was reflected as 150 leopard.

BLACK RHINOCEROS (Diceros bicornis)

-

The Minister points out further that the black rhinoceros was included in Appendix I in 1977. She says that at COP 13 (Bangkok, 2004) the parties approved an annual export quota of 5 black rhinoceros trophies from South Africa to deal with the problem of surplus male black rhinoceros and also to enhance demographic or genetic diversity goals. The Minister deals further with debates which took place at various COP’s thereafter which noted that in certain parts of sub-Saharan Africa, the black rhinoceros population had stabilized and was even increasing in some countries.

-

In the result, at COP 18 (Geneva, 2019) a proposal by South Africa to increase its black rhinoceros quota was accepted and the Republic is now permitted to export the trophies of “a number of adult male black rhinoceros not exceeding 0.5% of the population in South Africa in the year of export.” The proposed increase in the quota was scientifically motivated in some detail and was based, inter alia, on the increase in the population of black rhinoceros and the suggestion that an increase in the number of trophies for export would bring in additional revenue which might be put towards the expense associated with the upsurge in anti-poaching measures necessary to preserve the species overall in South Africa.

AFRICAN ELEPHANT (LOXODONTA AFRICANA)

-

The Minster notes that the African elephant was listed in Appendix I of CITES in 1990. Evidently, the interest in elephant trophies focusses on tusks which might be exported for the use of their ivory. In this regard the Minister points out that at COP10 (Harare 1997), it was recommended that member states which wished to authorize “the export of raw ivory as part of their elephant hunting trophies… should establish as part of its management of the population, an annual quota expressed as a maximum number of tusks and implement the provisions and guidelines in Resolution Conf. 14.7 (Rev. COP15) on Management of Nationally Established Export Quotas.”

-

As a consequence of the deliberations at COP 10 (Harare 1997) and as later revised at COP 18 (Geneva 2019), South Africa currently has an annual CITES quota for African elephant of 300 tusks from 150 animals.

THE 2021 QUOTA PROCESS

-

On 8 October 2021 the Minister gave notice in Government Gazette No. 45924 under Government Notice 1022 that she intended consulting on the 2021 quota for the export of hunting trophies of elephant, black rhinoceros and leopard. Given its centrality in this litigation, I recite the notice in full.

“I, Barbara Dallas Creecy, Minister of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment, hereby, in terms of section 99 and 100 of the National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act, 2004 (Act No. 10 of 2004), consult on the annual quota for hunting and/or export of elephant (Loxodonta africana), black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis) and leopard (Panthera pardus) hunting trophies for the 2021 calendar year, determined in accordance with subregulation 3(2)(k) of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) Regulations, 2010, published under Government Notice No. R173 in Government Gazette No. 33002 on 5 March 2010, as set out in the Schedule.

Members of the public are invited to submit to the Minister, within 30 days from the date of the publication of this notice in the Government Gazette, written representations on, or objections to, the proposed annual quota for hunting and/export of elephant, black rhinoceros and leopard hunting trophies for the 2021 calendar year to any of the following addresses…”

-

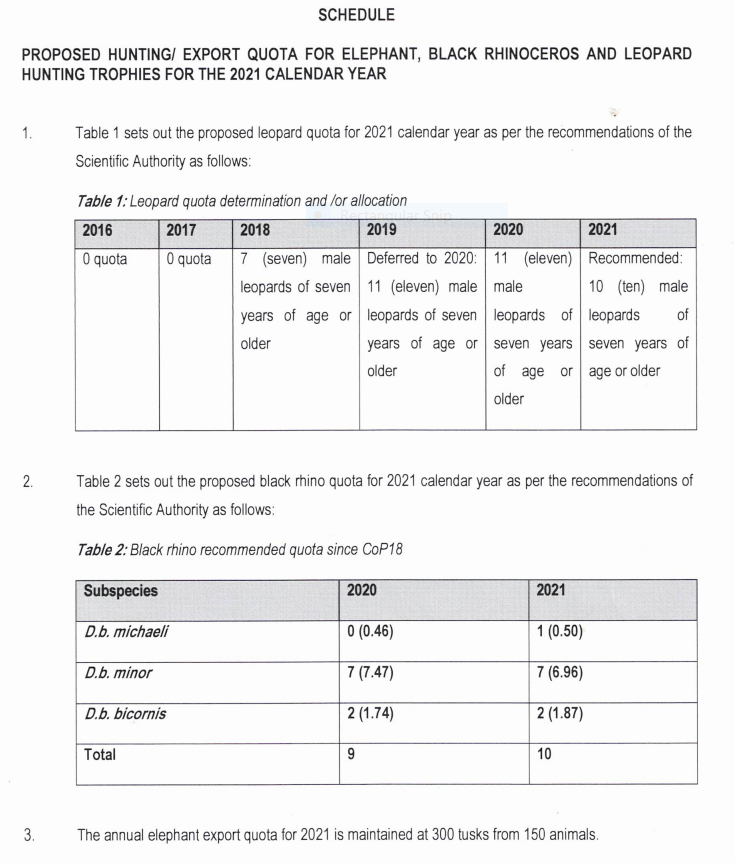

A

nnexed to the Minister’s notice was the following schedule which reflects details of the proposed quotas for each species in respect whereof consultation was invited.

nnexed to the Minister’s notice was the following schedule which reflects details of the proposed quotas for each species in respect whereof consultation was invited.

PUBLIC PARTICIPATION

-

As the founding affidavit reflects, HSI-Africa participated in the consultative process initiated by the Minister and, along with various other parties, delivered detailed objections to the proposed quotas: its representations are incorporated in the Minister’s answering affidavit and run to some 40 pages. The Minister was urged by HSI-Africa to apply a zero-based approach to the 2021 quotas in respect of all three species. The representations are detailed and comprise extensive scientific data and argument. Save for that which follows, HSI-Africa’s representations and its submissions on the merits of the review are not relevant for consideration of the interim relief sought under Part A of the notice of motion herein.

-

In regard to the trophy hunting of black rhinoceros, HSI-Africa commented that a critical scientific report was missing. It points out that in terms of Reg 6(3)(c) of the CITES Regs, a permit may only be granted for the export of any specimen listed in Appendices I and II once the scientific authority has evaluated the proposed quota, and, importantly, has made an NDF (“Non-Detriment Finding”). In regard to the 2021 quota for leopard, HSI-Africa accepts that the scientific authority has reported but it is critical of the evaluation of that report by the authorities and the Minister. In regard to black rhinoceros, HSI-Africa says that, while a draft was circulated earlier, no final NDF was submitted by the scientific authority for the 2021 quota.

SCIENTIFIC AUTHORITY

-

In terms of Article III.2 (a) of the Convention, an export permit for any species included in Appendix I “…shall only be granted when…a Scientific Authority of the State of export has advised that such export will not be detrimental to the survival of that species.”

-

The Scientific Authority is defined in the CITES Regs as the national scientific authority established under the TOPS Regs, which in turn cross-references the scientific authority referred to in s60 of NEMBA. In terms of s60(1) of NEMBA, the Minister is obliged to establish “a scientific authority for the purpose of assisting in regulating and restricting the trade in specimens of listed threatened or protected species and species to which an international agreement regulating international trade applies.”

-

S61(1) of NEMBA lists the several functions of the scientific authority which include,

(i) the monitoring of trade in listed threatened species (s61(1)(a);

(ii) making recommendations to the Minister on applications for permits sought under S57(1) of NEMBA – to hunt specimens protected under CITES (s61(1)(c)); and

(iii) the making of “non-detriment findings [NDF’s] on the impact of actions relating to the international trade in specimens of listed threatened or protected species and species to which an international agreement regulating international trade applies, and must submit those findings to the Minister” (s61(1)(d).

-

In terms of s61(2) the scientific authority is directed (“must”) to consult widely – with organs of state, the private sector, NGO’s, local communities - and then base its “findings, recommendations and advice on a scientific and professional review of available information.” The importance of the scientific authority’s NDF findings is highlighted in s62 of NEMBA which provides for the publication thereof by the Minister in the Government Gazette and the opportunity for a public participation process in relation thereto.

NDF FINDINGS

-

There is no criticism in the founding affidavit regarding the failure of the scientific authority to submit an NDF in respect of elephant. While Mr. Gerrans has much to say regarding for the case for a zero quota for elephant, the absence of an NDF is not alleged to be the basis therefor. It must thus be assumed for the purposes of this application that there is no objection by the scientific authority in terms of an NDF to the proposed trophy quota for elephant.

-

In regard to black rhinoceros, Mr. Gerrans says that, while the Minister published a draft NDF in respect of this species in 2019, no final document was issued. He thus asserts that there is no NDF in respect of black rhinoceros and that the Minister’s quota was thus determined in the absence of the mandatory report required under NEMBA. The absence of this report, it is said, renders the decision unlawful on the basis of the following dictum by Kollapen J in NSPCA.

“[23] Thus in broad terms the Minister is required to set an annual export quota but before doing so must consult the Scientific Authority who in turn must both make a non-detriment finding as required by NEMBA as well as base its findings, advice or recommendations on a broad level of public consultation as well as a scientific and professional review of available information.”

-

In respect of the proposed leopard quota, Mr. Gerrans says the following in the founding affidavit in regard to the mandatory requirement for an NDF.

“65. An NDF for leopard was issued but it was issued with specific conditions which have not been satisfied and so, the NDF is invalid.

66. In 2015 an NDF in respect of Leopards was published. However, the NDF stated that ‘recent research suggestions (sic) that trophy hunting may be unsustainable in Limpopo, KwaZulu Natal and possibly North West.’ The NDF identified significant threats to leopard populations, which included: habitat loss, ‘excessive off-takes5 (legal and illegal) of putative damage-causing animals (DCAs); poorly managed trophy hunting; the illegal trade in leopard skins for cultural and religious attire; incidental snaring and the unethical radio-collaring of leopards for research and tourism’ and ‘a lack of reliable monitoring of leopard populations.’

67. The NDF found that:

In conclusion, the non-detriment finding assessment (Figure 1) undertaken for Panthera pardus (leopard), as summarized in the analysis of the key considerations above, demonstrates that legal local and international trade in live animals and the export of hunting trophies at present poses a high risk to the survival of this species in South Africa (Figure 2A). This is mostly due to poor management of harvest practices and a lack of reliable monitoring of leopard populations.

68. On the Department’s own admission, hunting and export of leopard trophies poses threats to the survival of the species. These threats have not been mitigated against as required by the NDF.”

CERTAIN OF HSI-AFRICA’S SUBMISSIONS

-

In its 40-page submission document in response to the ministerial invitation to consult on the quotas, HSI-Africa said, inter alia, the following.

“Inadequate Timeframe for Adequate Management and Oversight

As there is less than two months remaining in 2021 and, allowing for adequate consideration of submissions regarding the hunting quota, the quota (be it zero or not) will be announced weeks after the comment submission due date (08 Nov 2021). This will result in only about a month remaining in the year to issue leopard hunting permits. This is insufficient time to allow for adequate administration and oversight of the leopard hunting quotas and increases the propensity of the permits being abused and/or conditions not being complied with. Hunts will be hastily completed and there is an increased likelihood that inherent welfare harms, identified above, will be exacerbated.”

-

HSI-Africa further noted that the Minister had not set out any criteria for her determination of the preferred quota for leopard trophies, thus allegedly rendering comment by interested parties difficult. After referring to certain guiding principles in ss2(1) and 2(4)(a) to (c) of NEMA (which is the over-arching legislation from whence NEMBA derives its principial approach to management of the environment), the submission by HSI-Africa concludes with the following remark.

“These principles mandate that activities creating environmental harm should only be allowed in special circumstances - where there is a great need for the activity to occur or, at the very least, where there is massive benefit accruing from the allowed activities. Given the small number of leopards hunted and the small amount of economic conservation benefits accruing from the leopard hunting (and considering the potential for social and economic harm, as well), as discussed above, it is unclear how the Minister could have adequately considered these [NEMA] principles and still allow a leopard hunting quota. The harm can be avoided and/prevented - there is no desperate need for leopard trophy hunting to occur in South Africa. The Minister must publish a zero leopard hunting quota for 2021 in order to avoid contravening the foundational NEMA principles.”

THE MINISTER’S DECISION

-

In the founding affidavit, Mr. Gerrans referred to a press release issued by the Department on 25 February 2022 announcing the Minister’s determination of the quotas on which she had called for consultation in October 2021. At that stage HSI-Africa assumed that this was the extent of the Minister’s decision for purposes of an application for review under the provisions of PAJA6 and the papers were drawn accordingly.

-

In her answering affidavit the Minister did not refer expressly to any document issued under her hand determining the quotas which preceded the issuing of the press release. Rather, in para 65 of her affidavit, the Minister obliquely alluded thereto in confirming the contents of the press release as “record(ing) the terms of a decision which I made in the exercise of my powers as the National Management Authority under regulation 3(2)(k) of the CITES Regulations to allocate annual quotas to provinces.”

It is apparent from this comment that there had been an earlier decision taken.

-

During his address on 18 March 2022, the Court pressed Mr. Magardie on the existence of any formal document presented by the Department to the Minister for authorization of the quotas. After the lunch adjournment, counsel handed up a detailed document of 20 pages which had been signed by the Minister on 31 January 2022, from which such authorization appeared. It was said that the Minister would confirm the applicability of that determination under oath later. After production of this document by counsel, it became common cause that the 31 January 2022 determination constituted the ministerial decision relevant to this matter.

-

In the result, on 31 January 2022 the Minister fixed the following quotas for the export of hunting trophies in accordance with the Schedule to the 8 October 2021 notice to consult.

-

10 male leopard of 7 years or older, to be hunted in the following Provinces, in the following numbers –

(i) Limpopo – 7;

(ii) KwaZulu Natal – 1; and

(iii) North West – 2.

-

10 black rhinoceros;

-

300 tusks from 150 elephant.

No provincial allocation or limitation was specified in respect of rhinoceros and elephant.

-

At the conclusion of her determination, the Minister made the following remark –

“The hunting/export quotas mentioned herein were published for public consultation with the expectation that they will be utilized in 2021. However, due to time constraints, I have decided to defer the implementation of these quotas to 2022.”

INTERIM ORDER OF 25 MARCH 2022

-

After the further hearing of the matter on 23 March 2022, the Court made an interim order on 25 March 2022 pending the handing down of this judgment. While the parties were encouraged to agree the terms of that interim order, they were unable to reach complete agreement and after hearing the parties briefly (and virtually) in chambers on that day the Court adopted the draft put up by HSI-Africa. In that order, the Minister’s decision of 31 January 2022 was suspended pending the delivery of this judgment and HSI-Africa was directed to draw the contents of the interim order to the attention of the various MEC’s responsible for the environment in each Province in the Republic.

-

The Minister was further directed to formally lodge her decision with the Court through a supplementary affidavit to be filed by 28 March 2022 and HSI-Africa was afforded an opportunity to file a further affidavit in response to the Minister’s supplementary affidavit by 8 April 2022, and to amend the relief sought herein in the event that it was considered necessary.

-

The Minister duly filed the affidavit as directed in the order of 25 March 2022 and confirmed that she had made her quota decision on 31 January 2022 in terms of the document which had been handed up earlier by Mr. Magardie, a copy whereof she annexed to her supplementary affidavit. The Minister indicated that she would deal further with the decision-making process in her affidavit in answer to the Part B relief – the review itself. In the result, HSI-Africa elected to file no further papers nor did it seek to amend its notice of motion.

-

Pursuant to subsequent correspondence directed to the parties by this Court’s registrar, HSI-Africa’s attorneys filed an affidavit confirming compliance with para 4 of the order of 25 March 2022 – furnishing proof of the fact that the 9 MEC’s in the various provinces charged with environmental compliance had been informed of the existence of this litigation.

INTERIM RELIEF SOUGHT

-

As the papers presently stand HSI-Africa seeks the following relief, in addition to prayers for urgency, costs and alternative relief.

“PART A

1…

2. Pending the determination of the relief sought in part B hereof:

2.1. The decision of the first respondent on or about 25 February 2022 to allocate a hunting export quota for elephant (Loxodonta africana), black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis) and leopard (Panthera pardus), for calendar year of 2022 is interdicted from being implemented or given effect to in any way.

2.2 The first respondent is interdicted from publishing in the Government Gazette or in any other way issuing a quota for the hunting and/or export of elephant (Loxodonta africana), black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis) and leopard (Panthera pardus).

2.3 The first respondent or any person so-delegated is interdicted from issuing any permit for the hunting and export of elephant (Loxodonta Africana), black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis) and leopard (Panthera pardus)…

AND, IN RESPECT OF PART B...

5. The decision of the first respondent on or about 25 February 2022 to allocate a hunting and export quota for elephant… black rhinoceros… and leopard for the calendar year 2022 is declared unlawful, reviewed and set aside.

6. The first respondent is directed to reconsider the allocation of a trophy hunting permit for elephant… black rhinoceros…and leopard for 2022 after engaging in a consulting process in compliance with Section 100 of the National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act 10 of 2004…”

THE REQUIREMENTS FOR AN INTERDICT PENDENTE LITE

-

The requirements for the granting of an interim interdict pendent lite are by now trite.7 The following dictum by Corbett J in LF Boshoff8 provides a useful summary of the correct approach.

“Briefly these requisites are that the applicant for temporary relief must show –

(a) that the right which is the subject matter of the main action and which he seeks to protect by means of interim relief is clear or, if it is not clear, is prima facie established, though open to some doubt;

(b) that, if the right is only prima facie established, there is a well-grounded apprehension of irreparable harm to the applicant if the interim relief is not granted and he ultimately succeeds in establishing his right;

(c) that the balance of convenience favours the granting of the of interim relief; and

(d) that the applicant has no other remedy.”

-

These criteria are all subject to the court’s overriding discretion. In his seminal work9, CB Prest notes the following.

“In every case of an application for an interdict pendent lite the court has a discretion whether or not to grant the application. It exercises this discretion upon consideration of all the circumstances and particularly upon a consideration of the probabilities of success of the applicant in the action. It considers the nature of the injury which the respondent, on the one hand, will suffer if the application is granted and he should ultimately turn out to be right, and that which the applicant, on the other hand, might sustain if the application is refused and he should ultimately turn out to be right. For though there may be no balance of probability that the applicant will succeed in the action, it may be proper to grant an interdict where the balance of convenience is strongly in favour of doing so, just as it may be proper to refuse the application where the probabilities favour the applicant, if the balance of convenience is against the grant of interim relief.

The exercise of the court’s discretion usually resolves itself into a nice consideration of the prospects of success and the balance of convenience - the stronger the prospects of success, the less the need for such balance to favour the applicant; the weaker the prospects of success, the greater the need for the balance of convenience to favour him.” (Internal references omitted.)

THE PRIMA FACIE RIGHTS RELIED UPON BY HSI-AFRICA FOR INTERIM RELIEF

-

In his address Mr. Morison SC referred to only two of the rights which HSI-Africa intended to rely on at the review hearing for the Part B relief in due course and which it was said had been established at the prima facie level for interim relief. Both of these rights were procedural in nature and counsel did not deal in any detail with the merits of the issues to be further argued at review.

-

Firstly, it was argued that the Minister was not statutorily permitted to advertise for consultation in relation to the fixing of a quota in a particular year and then apply the determination of the outcome of that consultative process in a subsequent year. This was dubbed the “roll over” process and I shall likewise refer to it thus.

-

The second prima facie right relied on related to the method of publication of the Minister’s decision. It was said, with reference to the interplay between NEMBA and the CITES Regs, that the ministerial quota decision in casu only acquired binding legal effect once the decision had been submitted to Parliament and it was thereafter published in the Government Gazette. It was for this reason that HSI-Africa originally formulated its notice of motion in the form of relief seeking to interdict the implementation of the decision reflected in the press release. Once the decision of 31 January 2022 was disclosed, the argument was adjusted accordingly.

THE “ROLL- OVER” ARGUMENT

-

In his address on 18 March 2022, Mr. Magardie fairly conceded that there was potential merit in the roll-over argument and preferred to focus his argument rather on the issues of balance of convenience and irreparable harm. I understood counsel to accept that the roll-over argument thus established (at least in part) the prima facie right contended for by HSI-Africa and I shall thus deal with it briefly.

-

It will be noted from the resolution of Conf. 10.14 referred to earlier that at Harare in 1997 the COP stressed the importance of ministerial quota decisions being restricted to individual calendar years. This has importance, so it would appear, in ensuring that the authorization for the hunting of a particular species is reviewed annually, inter alia, in the context of what the future effect on the species might be with due regard to historical quota determinations and general conditions affecting the species concerned.

-

In the passage quoted above, the COP at Harare explained, for the information of participating states, that the implementation of a quota fixed in a particular year may be spread over that and subsequent years. So, for example, in respect of a quota of say 20 leopard fixed in 2021, the hunting of that number may take place in 2021 (say 10 animals), 2022 (say 5 animals) and 2023 (the remaining 5 animals). This would be in addition to further quotas notionally fixed in the subsequent years (say 2022 and 2023).

-

But the approach sanctioned by CITES involving a partial postponement of the implementation of a quota for a specific period does not suggest that it is competent for the National Management Authority fixing a quota for 2021 to summarily postpone the entire implementation thereof to the following year, or for that matter to an even later period in time. The issue here turns on the procedural fairness to the parties participating in the quota determination for the calendar year of 2021 being told, after the completion of the process, that their objections and submissions were being considered and applied in a calendar year in respect whereof they had not been asked to comment. The prejudice to the public participants, which will no doubt include scientists and experts in conservation, of such an exercise is obvious, particularly in circumstances where there may be differing considerations from year to year.

-

I would imagine that it cannot be ignored, for example, that certain species have specific breeding seasons during the year which might be affected by natural disasters such as floods, drought and bush fires or an outbreak of a particular disease. One thinks here, for example, of an anthrax epidemic which might impact on the elephant population or a ravaging veld fire which wipes out large numbers of game.

-

Certainly in respect of elephant and rhinoceros, it is a notorious fact of which a court surely may take judicial knowledge that the poaching of these species (and in particular rhinoceros) in South Africa is rife. Whether there has been an uptick or decline of such poaching in a particular period is no doubt a consideration which might be raised by a participant in the public process. I must not be understood here to be suggesting any scientifically based assumptions relevant to this case, but rather a common sense approach impacting on the consideration of the status of a particular species, which might conceivably differ from one year to the next.

-

HSI-Africa complains, in particular, that the Minister’s decision to roll over the 2021 decision to 2022 was not only not authorized nor contemplated under the CITES Regs and thus unlawful, but that it violated the common law principle of legitimate expectation and was thus capable of review under PAJA. As to the former, there is, I believe, sufficient evidence before this Court to sustain a legality/lawfulness argument at least at the prima facie level.

-

Regarding the issue of legitimate expectation, it is true, as submitted by Mr. Magardie, that there is only a limited reference in para 90 of the founding affidavit to this fundamental pillar of procedural fairness in administrative law. But, an expectation of procedural fairness in a statutorily mandated process, where there has been a call for consultation, accords with the approach I have advocated above. It seems to me to be manifestly unfair to a party to invite it to consult on an issue (e.g. should permits be issued for trophy hunting of black rhinoceros in 2021) in which the decision-maker is statutorily time bound and then for her to apply that participative process to a time period in respect whereof there has factually been no consultation (e.g. should permits be issued for trophy hunting of black rhinoceros in 2022). Essentially, it means that there was no proper consultation in respect of the quota for 2022.

-

In her latest edition of the authoritative work on administrative law, Hoexter10 notes that the approach to the principle of legitimate expectation has undergone significant judicial interpretation and tweaking over the years since the seminal judgment of Corbett CJ in Traub11 and has consequently benefited from a more flexible approach in some cases. It may be that the reviewing court is persuaded by HSI-Africa to venture further down this broader path. I need say no more than that at this stage.

THE GOVERNMENT GAZETTE ARGUMENT

-

The second point put up on behalf HSI-Africa in relation to the establishment of a prima facie right on review relates to the purpose behind publication in the Government Gazette. In a well-reasoned argument, Mr. Prinsloo took the Court through the web of statutory provisions and regulations in order to demonstrate that such publication is essential to give statutory validity to the Minister’s quota decision. The submission posits that until the intended CITES quota has been referred to Parliament for the mandated 30-day period and then published in the Gazette as a regulation and not just for public information, the decision is of no force and effect.

-

Mr. Magardie, on the other hand, submitted that the gazetted notice contemplated by the Minister was purely for purposes of informing the public of the outcome of the process and that the decision already has legal validity. It was said that the official position in relation to publication is to be found in the Minister’s decision of 31 January 2022, in which she approved the recommendations by the Director General of the Department that she should –

“5.3 approve the attached media statement, informing members of the public about the deferral of the 2021 quotas and allocation of 2021 CITES hunting/export quotas for African Elephant, Black Rhino and Leopard trophies…

5.5 sign the attached Government Notice to be published in the Government Gazette, informing members of the public about the deferral of the 2021 quotas and allocation of 2021 hunting/export quotas for African Elephant, Black Rhino and Leopard.” (Emphasis added)

-

While the issue may at first blush seem somewhat arcane, there is material importance in the argument put forward by HSI-Africa. With reference to s97(3A) of NEMBA, it is suggested that before the decision can be published in the Government Gazette, it must have been submitted to Parliament 30 days prior to such publication and the failure to do so raises material separation of powers concerns.

-

Central to the HSI-Africa argument is the question whether, when the Minister makes a quota determination, she acts only under the CITES Regs or whether her power to regulate the quota is sourced in NEMBA. It is not necessary at this stage to make a definitive finding on this issue: the question is only whether a prima facie case has been made out to show that the point is arguable on review.

-

The point of departure is s97 of NEMBA which deals, inter alia, with the Minister’s power to make regulations under that Act. In terms of s97(1)(b)(iv) the Minister is empowered to make regulations relating to -

“the facilitation of the implementation and enforcement of an international agreement regulating international trade in specimens of species to which the agreement applies and which is binding on the Republic.”

As the preamble thereto reflects, the erstwhile Minister acted under that section of NEMBA when she made the CITES Regs.

-

However, HSI-Africa contends that the ministerial power to fix a quota such as that in question is not sourced in the CITES Regs but in s97(1)(b)(viii) of NEMBA which permits her to make regulations in relation to –

“the ecologically sustainable utilization of biodiversity, including –

(aa) limiting the number of permits for a restricted activity”

-

This subsection must be read in the context of the definitions contained in s1 of NEMBA which provide that the meaning of a “restricted activity” includes

“(a) in relation to a specimen of a listed threatened or protected species, means –

(i) hunting, catching, capturing or killing any living specimen of a listed threatened or protected species by any means, method or device whatsoever, including searching, pursuing, driving, lying in wait, luring, alluring, discharging a missile or injuring with intent to hunt, catch, capture or kill any such specimen…

(v) exporting from the Republic, including re-exporting from the Republic, any specimen of a listed threatened or protected species…”

-

The term “specimen” is defined widely in s1 of NEMBA to include –

“(a) any living or dead animal…

(c) any derivative of any animal...

(d) any goods which –

(i) contain a derivative of an animal…”

-

Consequently, so it is argued, when the Minister issued the CITES quota for the “hunting/export” of the 10 leopard, the 10 black rhinoceros and 150 African elephant contemplated in this case, she was in fact authorizing 170 permits for both the hunting of the species and the subsequent export of the trophies thereof (in the form of derivatives of the leopard etc. so hunted). It was further contended that, while the CITES Regs placed the functional duty to determine the quota on the Minister, the statutory power to do so was sourced only in s97 of NEMBA. Each individual quota decision is thus said to be the subject of an individual regulation to be made by the Minister under NEMBA.

-

Expanding on that argument, counsel observed that the CITES Regs do not provide for any consultative or public participation process to be embarked upon by the Minister when determining a quota. That process is stipulated in s97(3) of NEMBA which provides that –

“Before publishing any regulations in terms of subsection (1), or any amendment to the regulations, the Minister must follow a consultative process in accordance with sections 99 and 100.”

And, if regard be had to the Minister’s notice to consult reflected above, it is apparent that she correctly (it was submitted) purported to act in terms of the said ss 99 and 100.

-

The submission went on to note that once she had so consulted and had made her quota determination, the Minister was required to observe s97(3A) of NEMBA which requires that

“Any regulations made in terms of this Act must be submitted to Parliament 30 days prior to the publication of the regulations in the Gazette.”

While NEMBA does not expressly state the reason therefor, it would appear that the Legislature wished to expressly provide for parliamentary oversight of the Minister’s regulatory functions under that Act.

-

In the result, HSI-Africa contends that the ultimate purpose of the review is to ensure that the Minister complied with her statutory functions under NEMBA. The interim interdict in turn would ensure that no publication of her decision is effected in the Government Gazette otherwise than in accordance with the process which it suggests is prescribed by NEMBA. In other words, the Minister’s decision is to be held in abeyance while the legality thereof is determined by the reviewing court in due course.

-

Given the relatively low bar which is set for the establishment of a prima facie right – and which according to Corbett J’s dictum may be open to some judicial doubt at this stage - I am satisfied that HSI-Africa has cleared the hurdle in setting up such a right on the Gazette argument as well. Put otherwise, I cannot say at this stage that the argument is devoid of merit.

ISSUES RELATING TO THE MERITS

-

Aside from the two prima facie rights which I have dealt with, there are various substantive issues raised in the founding papers which more properly fall for determination under the Part B relief sought at review. I shall deal with just two such issues.

-

Firstly, and as foreshadowed above, it is said that the scientific authority had failed to address the requisite NDF requirements for black rhinoceros, while the report in relation to the NDF status of leopard was seriously flawed. If these allegations are correct, they would certainly provide a basis for mounting a substantive attack on the validity of the 2021 quota determination.

-

Further, there is the complaint by HSI-Africa that the Ministerial notice announcing consultation was defective in that it did not provide sufficient information under s100(2)(b) of NEMBA –

“to enable members of the public to submit meaningful representations or objections.”

Reference was made in argument in this regard to Kruger12 and Fly Fishers13. While this Court is not in a position to resolve this issue, it must be said at this stage that it cannot be said that the review is without merit on the complaint of non-compliance with NEMBA. I say no more than that the point appears to be arguable.

IRREPARABLE HARM AND BALANCE OF CONVENIENCE

-

It is convenient to consider these criteria together. In the event that no interdict is granted pending finalisation of the review proceedings, of the order of 170 animals will be hunted during 2022, their respective trophies mounted by local taxidermists and thereafter exported overseas. The primary beneficiaries of these killings will be the wealthy, foreign hunters who may wish to adorn their homes, man-caves, offices, club houses and the like with the hubristic consequences of their expensive forays into the wilds of southern Africa. If the interdict is granted, those animals will be spared death at the hands of the hunters. The irreparable harm is thus the difference between life and death. It is, to use the vernacular, “a no brainer” in the test for an interdict pendent lite.

-

The Minister says in her answering affidavit that irreparable harm will be caused to the hunting industry by virtue of the lost opportunities in circumstances where hundreds of thousands of US Dollars would have been paid by those hunting for trophies. That argument is refuted by HSI-Africa in its reply, firstly, on the basis that the Minister’s contention as to the loss of financial opportunities is based on flawed data and, secondly, on the basis that South Africa has an unblemished international reputation for wildlife tourism and that the sums generated in that regard significantly outweigh the alleged income from trophy hunting.

-

In my view, the current impasse falls to be resolved in terms of the balance of convenience. The inconvenience to the Minister is that permits for the 2021 calendar year quota will not be issued by the MEC’s pending the hearing of the review. That does not mean that the financial considerations flowing therefrom are lost forever and a day. In the event that the review fails, the quota for 2021 will stand and be capable of implementation. In addition, the Minister would be permitted, for instance, under the aforementioned decision taken at Harare in 1997, to split that allocation over ensuing years.

-

Further, there is nothing precluding the Minister from forthwith abandoning the 2021 “roll-over” decision and commencing the process for 2022 afresh. There are still 8 months left in the calendar year and given the speed with which the previous exercise was conducted, it is conceivable that a valid quota for 2022 might be taken with something like 5 months or more available for its implementation, as opposed to the 6 weeks or so which were considered too short for the 2021 quota decision.

-

In finding that the balance of convenience favours the applicant here, I can do no better than to quote from the founding affidavit of Mr. Gerrans.

“92. The balance of convenience clearly favours the granting of the relief. If the interdict is not granted, the black rhino, elephant and leopard population may be irreversibly affected, the welfare of individual elephants, black rhino and leopards will have been harmed and the rights claimed above will have been lost. No permits have, to HSI-Africa’s knowledge, been issued as of yet because the quota has not yet been published. There are accordingly no parties who have claimed permits and relied thereon as of yet.”

And, in any event, as I have said, if the review is unsuccessful, the desire of the fortunate few who can afford to hunt protected animals exclusively for the purpose of transporting their trophies for display overseas will not have been lost, only delayed. So too the much vaunted inflow of foreign currency into South Africa’s hunting industry.

OUTA

-

The last point that must be dealt with in relation to the balance of convenience is the Minister’s reliance on the judgment of the Constitutional Court in OUTA14. The submission by Mr. Magardie was to the effect that a court considering whether to grant a temporary restraining order on the exercise of statutory power must, when evaluating the balance of convenience, consider the harm that may be caused to the separation of powers principle. The preferred approach was stated as follows by Moseneke DCJ-

“[26] A court must also be alive to and carefully consider whether the temporary restraining order would unduly trespass upon the sole terrain of other branches of Government even before the final determination of the review grounds. A court must be astute not to stop dead the exercise of executive or legislative power before the exercise has been successfully and finally impugned on review. This approach accords well with the comity the courts owe to other branches of Government, provided they act lawfully…

[47] The balance of convenience enquiry must now carefully probe whether and to which extent the restraining order will probably intrude into the exclusive terrain of another branch of Government. The enquiry must, alongside other relevant harm, have proper regard to what may be called separation of powers harm. A court must keep in mind that a temporary restraint against the exercise of statutory power well ahead of the final adjudication of a claimant’s case may be granted only in the clearest of cases and after a careful consideration of separation of powers harm. It is neither prudent nor necessary to define “clearest of cases”…

[66] A court must carefully consider whether the grant of the temporary restraining order pending a review will cut across or prevent the proper exercise of a power or duty that the law has vested in the authority to be interdicted. Thus courts are obliged to recognise and assess the impact of temporary restraining orders when dealing with those matters pertaining to the best application, operation and dissemination of public resources. What this means is that a court is obliged to ask itself not whether an interim interdict against an authorised state functionary is competent but rather whether it is constitutionally appropriate to grant the interdict…” (Internal references omitted)

-

This Court is mindful of the fact that the granting of the order sought by HSI-Africa may trench upon the Minister’s internationally mandated executive power to fix a quota for trophy hunting of protected species during 2021. However, in weighing up the balance of convenience, I have concluded that the effect of allowing the determination to stand and be implemented in 2022 will totally destroy the number of animals affected by that determination and, most crucially, there is nothing that can be done to replace that destruction in future if the review is successful.

-

On the other hand, as I have suggested, the temporary suspension of the implementation of the 2021 quota will not operate unduly harshly if the review does not succeed: the designated number of each species will still be available to be hunted in such event. Further, the order sought will not operate to restrain the Minister from taking her mandated decision for the 2022 calendar year.

-

Furthermore, it is not in dispute that the purpose of this application is to advance the constitutionally protected interests which HSI-Africa enjoys under the s24 (b) of the Constitution. When the Minister’s compliance with her obligations under NEMBA and the CITES Regs are ultimately considered this provision of the Constitution will similarly come into play through the principle of subsidiarity. Consequently, her decision will be evaluated with reference to, inter alia, both animal welfare and the interests of trophy hunters.15

-

Given the potential for the permanent consequences of the violation of HSI-Africa’s s24 rights in the event that the 2021 decision is permitted to be implemented, I consider that the concerns addressed by Moseneke DCJ in OUTA are adequately addressed and that the grant of an interim interdict in the present matter will not violate the separation of powers principle. This Court is, I believe, dealing with what the Constitutional Court has termed a “clear case.”

NON-JOINDER

-

Lastly, there is the question of non-joinder. In argument Mr. Magardie submitted that there had been a failure to join the nine MEC’s responsible for issuing the CITES permits in the respective Provinces. The point was stressed that these were the functionaries responsible for the implementation of the ministerial quota and that they were thus entitled to be informed of the litigation and be heard if they so wished. Mr. Morison argued that the purpose of the interdict was to nip in the bud the implementation of the Minister’s decision before it devolved to the level of provincial implementation. To this extent, it was said, the MEC’s had no interest in the matter at this stage.

-

In her answering affidavit the Minister referred to a letter from the KwaZulu-Natal environmental department in which it was suggested that the Province might suffer financial hardship if it was not allowed to issue CITES permits in respect of elephant trophy hunting in 2022. The Minister’s concerns were ultimately addressed by the parties in the agreed portion of the draft order of 25 March 2022 in which provision was made for HSI-Africa’s attorneys to formally inform the MEC’s in writing of the litigation. These attorneys subsequently filed a supplementary affidavit confirming compliance with this part of the order.

-

As pointed out above, under Reg 3(5)(m) of the CITES Regs, the MEC’s as the Provincial Management Authorities have the power to intervene in proceedings such as these and, notwithstanding due notice, no MEC has elected to participate in this application. There is therefore no merit in the non-joinder argument and, in any event, no demonstrable prejudice that has been occasioned by the formal non-joinder of the Provincial Management Authorities.

CONCLUSION

-

In the light of the aforegoing I conclude that a proper case has been made out for the relief sought. Mr. Morison suggested that the costs of these proceedings should stand over for determination by the Court hearing the Part B relief. I agree.

IN THE CIRCUMSTANCES THE FOLLOWING ORDER IS MADE:

-

A. The forms, service and time periods provided for in the Rules of this Court are dispensed with and this application is heard on an urgent basis in terms of Rule 6(12)(a).

-

B. Pending the determination of the relief sought in part B of the notice of motion dated 10 March 2022, filed under the abovementioned case number:

-

(i) The decision of the first respondent on or about 31 January 2022 to allocate a hunting and export quota for elephant (Loxodonta africana), black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis) and leopard (Panthera pardus), for the calendar year of 2022 is interdicted from being implemented or given effect to in any way.

-

(ii) The first respondent is interdicted from publishing in the Government Gazette or in any other way issuing a quota for the hunting and/or export of elephant (Loxodonta africana), black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis) and leopard (Panthera pardus).

-

(iii) The first respondent or any person so-delegated is interdicted from issuing any permit for the hunting and export of elephant (Loxodonta africana), black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis) and leopard (Panthera pardus).

-

C. The issue of costs shall stand over for consideration during the hearing of part B of the relief sought.

__________________

GAMBLE, J

APPEARANCES

For the applicants: Mr. L.J.Morison SC, with him

Mr. B.Prinsloo

Instructed by Lopes Attorneys Inc.

Johannesburg

c/o Assheton – Smith Ginsberg Inc.

Cape Town.

For the respondents: Mr. S.Magardie

Instructed by The State Attorney

Cape Town.

1NSPCA v Minister of Environmental Affairs and others 2020 (1) SA 249 (GP) at [57] et seq.

224. Environment

Everyone has the right –

(a)…

(b) to have the environment protected, for the benefit of present and future generations, to reasonable legislative and other measures that –

(i)…

(ii) promote conservation; and

(iii) secure ecologically sustainable development and use of natural resources while promoting justifiable economic and social development.

338. Enforcement of rights.

Anyone listed in this section as the right to approach a competent court, alleging that a right in the Bill of Rights has been infringed or threatened, and the court may grant appropriate relief, including a declaration of rights. The persons who may approach the court are –

(a) anyone acting in their own interest…

(d) anyone acting in the public interest; and

(e) an association acting in the interest of its members.

432. Legal standing to enforce environmental laws.

(1) Any person or group of persons may seek appropriate relief in respect of any breach or threatened breach of any provision of this Act, including a principal contained in Chapter 1, or of any provision of a specific environmental management Act, or of any other circuitry provision concerned with the protection of the environment or the use of natural resources –

(a) in that person's or group of person’s own interest…

(d) in the public interest; and

(e) in the interest of protecting the environment.

5Evidently a scientific synonym for ‘killing’.

6The Promotion of Administrative Justice Act, 3 of 2000.

7See generally in that regard, Erasmus, Superior Court Practice Vol 2 at D6-1 et seq.

8LF Boshoff Investments (Pty) Ltd v Cape Town Municipality 1969 (2) SA 256 (C) at 267A-F

9The Law and Practice of Interdicts at 79

10Hoexter and Penfold Administrative Law in South Africa, 3rd ed at 576 et seq

11Administrator, Transvaal and others v Traub and others 1989 (4) SA 731 (A)

12Kruger and another v Minister of Water and Environmental Affairs and others [2016] 1 All SA 565 (GP)

13The Federation of South African Fly Fishers v The Minister of Environmental Affairs [2021] ZAGPPHC 575 (10 September 2021)

14National Treasury and others v Opposition to Urban Tolling Alliance and others 2012 (6) SA 223 (CC) at [26], [46] – [47] & [65] – [66]

15NCPCA at [74]