- Flynote

-

Trade Marks Act 193 of 1994 – shape mark in respect of a water bottle – whether such is distinctive as a trade mark as envisaged in s 9(2).

Passing-off – likelihood of confusion between appellants’ water bottle and that of first respondent.

THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEAL OF SOUTH AFRICA

JUDGMENT

Reportable

Case No: 636/2021

In the matter between:

DART INDUSTRIES INCORPORATED FIRST APPELLANT

TUPPERWARE SOUTHERN AFRICA (PTY) LTD SECOND APPELLANT

and

BOTLE BUHLE BRANDS (PTY) LTD FIRST RESPONDENT

COMPANIES AND INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY

COMMISSION SECOND RESPONDENT

Neutral citation: Dart Industries Incorporated and Another v Botle Buhle Brands (Pty) Ltd and Another (636/2021) [2022] ZASCA 170 (1 December 2022)

Bench: DAMBUZA, MAKGOKA and GORVEN JJA and GOOSEN and MASIPA AJJA

Heard: 6 September 2022

Delivered: 1 December 2022

Summary: Trade Marks Act 193 of 1994 – shape mark in respect of a water bottle – whether such is distinctive as a trade mark as envisaged in s 9(2).

Passing-off – likelihood of confusion between appellants’ water bottle and that of first respondent.

___________________________________________________________________

ORDER

___________________________________________________________________

On appeal from: Gauteng Division of the High Court, Pretoria (Louw J, sitting as a court of first instance):

1 The appeal against the order of the high court upholding the first respondent’s counter-claim is dismissed with no order as to costs.

2 The appeal against the order of the high court dismissing the appellants’ claim based on passing-off is upheld with no order as to costs.

3 The order of the high court is set aside and replaced with the following order:

‘1 The applicants’ application in respect of trade mark infringement is dismissed;

2 The respondent’s counter-application for the cancellation of the trade mark registered in the name of the first applicant, succeeds.

3 It is ordered that the South African trade mark no. 2015/25572 is to be cancelled in the Register of Trade Marks;

4 The applicants’ claim based on passing-off succeeds.

5 The respondent is restrained and interdicted from passing off its water bottle as being the first applicant’s Eco bottle, and/or part of the Eco bottle range and/or as being connected with the first applicant’s Eco bottle by making use of its water bottle or any other bottle shape confusingly similar to the first applicant’s Eco bottle.

6 Each party shall pay its own costs.’

___________________________________________________________________

JUDGMENT

___________________________________________________________________

Makgoka JA (Dambuza and Gorven JJA and Goosen and Masipa AJJA

concurring):

[1] This is a trade mark dispute about a shape of a water bottle. In the Gauteng Division of the High Court, Pretoria (the high court), the appellants sought to interdict the first respondent from infringing their registered trade mark for a water bottle. In turn the first respondent, counter-applied for the cancellation of registration of the trade mark. The high court granted the first respondent’s counter-application and ordered the cancellation of the mark. Consequently, it found it unnecessary to decide the infringement issue. The high court also dismissed the appellants’ claim based on passing-off. The appeal is with the leave of the high court.

[2] The first appellant, Dart Industries Incorporated, and the second appellant, Tupperware Southern Africa (Pty) Ltd, are part of the Tupperware group of companies, with Tupperware Brands Corporation, a United States of America (USA) entity, as the ultimate holding company. The first appellant develops and manufactures a range of products which includes plastic preparation, storage, kitchen, and home serving products under the well-known trade mark, Tupperware. The second appellant is its South African representative and the licensee of its intellectual property rights in this country. It also manufactures and sells Tupperware products in South Africa.

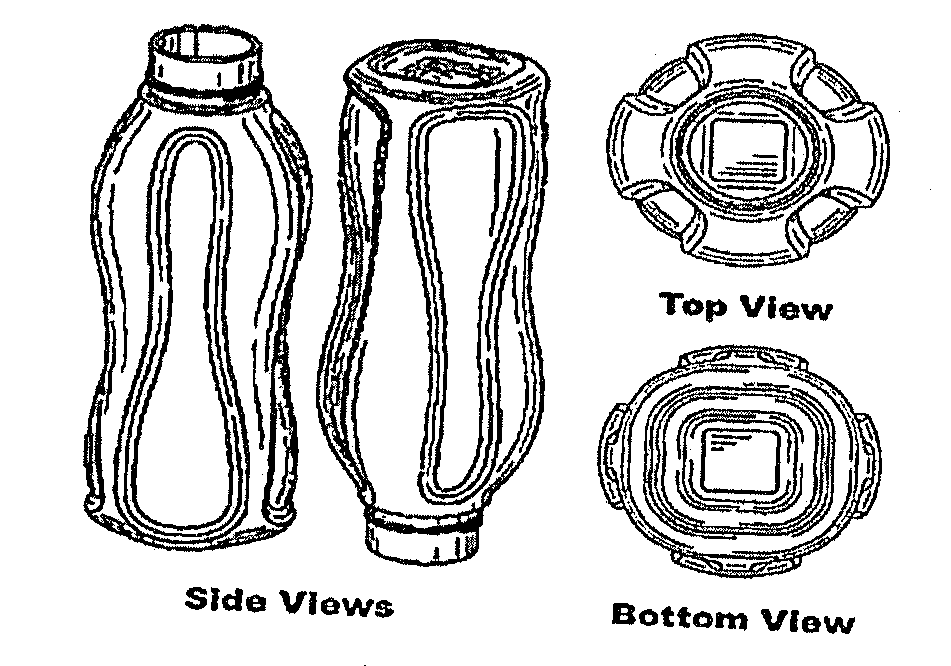

[3] The first appellant is the registered proprietor of South African trade mark registration no 2015/25572 ECO BOTTLE in class 21, with the effective date of the trade mark as 10 September 2015. The mark is registered for ‘household containers; kitchen containers; water bottles sold empty; insulated bags and containers for domestic use; beverage ware; drinking vessels.’ It is endorsed as consisting of ‘a container for goods’, and its representation in the trade marks register is as follows:

[4] It is convenient to refer to the first and second appellants jointly as ‘Tupperware’. Since 2011, Tupperware has been selling a plastic bottle that has the shape of the registered mark, and marketed as the ‘Eco bottle’, in South Africa. In 2019, the first respondent, Botle Buhle Brands (Pty) Ltd (Buhle Brands), a South African company that sells ‘homeware, cosmetics, toiletries, health and wellness, and fashion products,’ started to market and sell the allegedly infringing water bottle. Here is the depiction of Buhle Brands’ bottle:

[5] Tupperware considered the Buhle Brands’ bottle to infringe its registered trade mark. Accordingly, it applied to the high court seeking to restrain Buhle Brands from infringing its registered mark in terms of ss 34(1)(a) and 34(1)(c) of the Trade Mark Act 194 of 1993 (the Act). In addition, Tupperware sought a restraining order based on passing off. In response, Buhle Brands launched a counter-application for the removal of Tupperware’s trade mark registration based on several sections of the Act, namely: (a) s 10(2)(a) – that it was not capable of distinguishing Tupperware goods from those of other traders and was therefore, an entry wrongly made and/or wrongly remaining on the trade mark register in terms of s 24 of the Act; (b) s 10(4) – that the mark was registered without any intention of using it as such in relation to the goods for which it was registered; (c) s 10(11), the mark was likely to limit the development of any art or industry; and (d) s 27(1)(a) – that there was no bona fide intention to use the mark in relation to Tupperware’s goods.

[6] In the end, the high court decided the matter on the basis of the first ground, ie s 10(2)(a). Section 10, titled ‘Unregistrable trade marks’, provides a list of unregistrable marks. If such a mark is registered, it shall be liable to be removed from the register. One such mark is one which ‘is not capable of distinguishing within the meaning of section 9,’ which provides as follows in sub-section 1:

‘In order to be registrable, a trade mark shall be capable of distinguishing the goods or services of a person in respect of which it is registered or proposed to be registered from the goods or services of another person either generally or, where the trade mark is registered or proposed to be registered subject to limitations, in relation to use within those limitations.’

[7] The high court found that the registered trade mark was neither inherently distinctive nor had acquired distinctiveness as a result of prior use, as envisaged in s 9(2). Consequently, it dismissed Tupperware’s application and granted Buhle Brands’ counter application for the removal of Tupperware's trade mark from the trade mark register. This finding made it unnecessary for the high court to decide the infringement issue, or Buhle Brands’ grounds for removal based on ss 10(4), 10(11), and 27(1)(a). As regards the relief based on passing off, the high court found that although the bottles were virtually identical, there was no likelihood of deception or confusion, given the sales model used by both parties.

[8] Like the high court, I find it convenient to consider first, whether the shape of Tupperware’s Eco bottle as a mark is liable to be removed from the register in terms of s 10(2)(a) as being incapable of distinguishing within the meaning of s 9(2). The latter section provides as follows:

‘A mark shall be considered to be capable of distinguishing within the meaning of subsection (1) if, at the date of application for registration, it is inherently capable of so distinguishing or it is capable of distinguishing by reason of prior use thereof.’

[9] Thus, the sub-section provides for two forms of distinctiveness: inherent distinctiveness and acquired distinctiveness. A mark is inherently distinctive if, by its very nature, it identifies the goods or services in relation to which registration has been applied for as originating from a particular undertaking, and thus distinguishing those goods or services from goods or services of other undertakings. As regards acquired distinctiveness, a mark that is not inherently distinctive can acquire distinctiveness by reason of prior use.

[10] As explained in Beecham v Triomed1 (Beecham), the enquiry envisaged in sub-section 9(2) is a factual one, which is done in two stages. The first is whether the mark, at the date of application for registration, was inherently capable of distinguishing the goods of one trader from those of another person.2 If the answer is no, the next inquiry is whether the mark is presently so capable of distinguishing by reason of its use to date.3 Whether a mark possesses inherent or acquired distinctiveness is a question of fact that must be determined with regard to all the circumstances of each case. The relevant circumstances include ‘the nature of the mark and of the goods or services, the industry in which the mark is used’, and, ‘the perception of the average consumer in that industry.’4

[11] Was Tupperware’s mark inherently distinctive? To answer this question, it is well to bear in mind that the function of a trade mark is to indicate the origin of the goods or services.5 Thus, the public perception of a shape mark is crucial. In Beecham this Court accepted that members of the public must regard the shape of the particular goods as a guarantee of the source of those goods. This would be the case where a shape is markedly unique or extensively used. There are two instances here: on the one hand, the public might simply recognise a product by its shape. This is not sufficient for the shape to play the role of a trade mark. On the other, the public might rely on the distinctiveness of the shape as an indicator of the source of goods. It is the latter instance that denotes the shape as a trade mark.

[12] In terms of s 2(1) of the Act, a ‘mark’ is defined as ‘any sign capable of being represented graphically, including a device, name, signature, word, letter, numeral, shape, configuration, pattern, ornamentation, colour or container for goods or any combination of the aforementioned’. Thus, it is permissible to register a shape as a trade mark. In Bergkelder Bpk v Vredendal Koöp Wynmakery6 (Bergkelder) this Court considered a trade mark dispute about a container mark in the form of a wine bottle. It was pointed out that shape and container marks ‘do not differ from any other kind of trade mark’, and that ‘the criteria for assessing their distinctive character . . . are no different from those applicable to other categories of trade mark.’7 However, ‘from a practical point of view they stand on a different footing’8 because ‘average consumers are not in the habit of making assumptions’ about the origin of products based on shapes.9

[13] Emphasising the weakness of shape marks as indicators of origin, the Court referred to a passage in Bongrain SA’s Trade Mark Application [2005] RPC 14, where Jacob LJ said:

‘… [t]he kinds of sign which may be registered fall into a kind of spectrum as regards public perception. This starts with the most distinctive forms such as invented words and fancy devices. In the middle are things such as semi-descriptive words and devices. Towards the end are shapes of containers. The end would be the very shape of the goods. Signs at the beginning of the spectrum are of their very nature likely to be taken as put on the goods to tell you who made them . . . But, at the very end of the spectrum, the shape of goods as such is unlikely to convey such a message.’

[14] This Court in Bergkelder went on to survey a number of leading American, English and European Union authorities on shape and container marks. I distil the following broad principles from the authorities referred to in paras 7-10 of Bergkelder: First, the public is not used to mere shapes conveying trade mark significance. Containers are usually perceived to be functional and, if not run of the mill, to be decorative and not badges of origin. Second, merely because a product shape is both new and visually distinctive, and likely to be recognised as different to others on the market, does not mean that it would convey that it was intended to be an indication of origin or that it performed that function. Third, even a very fancy shape is not necessarily enough to confer on it an inherently distinctive character. In other words, just because a shape is unusual for the kind of goods concerned, the public will not automatically take it as denoting trade origin, as being the badge of the maker.

[15] Lastly, since containers are not usually perceived to be source indicators, a container mark must, in order to be able to fulfil a trade mark function, at least differ ‘significantly from the norm or custom of the sector’.10 Only a shape which departs significantly from the norm or customs of the sector and thereby fulfils its essential function of indicating origin, has a distinctive character. However, the mere fact that it so differs does not necessarily mean that it is capable of distinguishing, as the question remains whether the public would perceive the container to be a badge of origin and not merely another vessel.

[16] The essence of these authorities is that there are considerable difficulties in the path of traders who contend that the shape of their goods itself has trade mark significance. It is against these principles that the enquiry as to whether Tupperware’s mark is inherently distinctive should be undertaken. Tupperware contended that its Eco bottle ‘departs significantly’ from the shape of other water bottles in the market and that the use of an hourglass shape with indentations was unique and unknown to the market when it launched the Eco 10 bottle in South Africa. There are three steps in deciding whether the mark differs significantly from the norms and customs of the sector. The first step in the exercise is to determine what the sector is. Then it is necessary to identify common norms and customs, if any, of that sector. Thirdly it is necessary to decide whether the mark departs significantly from those norms and customs.11

[17] In the present case, the evidence reveals that at the time of the launch of the Eco bottle, other traders were marketing their water bottles with an hourglass shape – the shape of the registered trade mark, albeit of varying configurations. Tupperware submitted that the Eco bottle was markedly different from any of those on the market. It conceded, though that at least two of them were virtually identical to Tupperware’s Eco bottle, and that steps were being taken against the proprietors of those bottles. The high court said the following of those bottles:

‘What is, however, clear from the annexures to [Buhle Brands'] answering affidavit is that there is a substantial amount of different shaped water bottles with hour-glass shapes and indentations which were registered on the trade marks register before [Tupperware] applied to register its mark in 2015. Even if it is accepted that Tupperware's ECO water bottle was at the date of application for registration of the mark significantly different from other water bottles with hour-glass shapes and indentations, the public would, in my view, not perceive [Tupperware’s] ECO water bottle to be a badge of origin, but would merely see it as just another water bottle.’

[18] I cannot fault this reasoning. The Eco bottle does not represent a significant departure from the norms and customs of the water bottle sector. What is more, there is no evidence that the average consumer appreciates that the bottle conveys trade mark significance. Applying some of the general principles distilled from Bergkelder, I do not think that customers would regard the shape of the Eco bottle alone as a guarantee that it was produced by Tupperware, as ‘containers and shapes generally do not serve as sources of origin.’ The Eco bottle is certainly visually distinctive, and would be recognised as different to other bottles on the market. But this does not mean that it would ‘convey a message that it was intended to be an indication of origin or that it performed that function.’

[19] Having compared the Eco bottle to what was on the market when Tupperware applied to register its mark in 2015, I do not consider the mark to ‘differ significantly’ from the norm or custom of the sector to be able to fulfil a trade mark function in the manner required by the authorities referred to in Bergkelder.’ I think that the average consumer would see the shape of the Eco bottle as representing no more than a fancy, trendy or more appealing, water bottle. The shape was within the norms and customs of the water bottle sector and was merely a variant of common shapes for water bottles. An average consumer would not distinguish the Eco bottle from those of other entities in a trade mark sense. The high court was therefore correct to hold that the Eco bottle did not have an inherently distinctive character.

[20] I turn to consider whether the Eco bottle has acquired distinctiveness as a result of prior use. Section 9(2) carves out an exception to allow the registration of marks which lack inherent distinctiveness, if by reason of prior use, a mark has acquired distinctiveness. The question therefore arises: how does an inherently non-distinctive mark acquire distinctiveness such that it does function as a trade mark? The applicable test for acquired distinctiveness is by no means settled. There are mainly three tests in this regard. Tsele12 sums it up neatly:

‘There are those who advocate for a test which asks whether consumers “recognise” the mark and “associate” it with the trade mark claimant’s goods. This is what we can call the recognition-and-association test. On the opposite end of the spectrum lies what has been called “the reliance test”, which requires proof that a relevant class of consumers “rely” on the (shape) mark as an indicator of the source of the goods. But there seems to be a third — intermediate — test that proponents call “the perception test”. There is yet another, fourth test, styled “the identification test”, which one court has suggested.’13

[21] The ‘reliance’ test was seemingly applied by this Court in Beecham, where the dispute was about a trade mark for the shape of a pharmaceutical tablet. Beecham had registered a trade mark for the shape of a tablet called Augmentin. The registered mark was of a biconvex, oval shape of a tablet. Triomed, the respondent, was the importer of a pharmaceutical with the same composition as Augmentin and sold it under the name Augmaxil, which had the same shape and white colour as the Augmentin tablets. However, whereas the name ‘Augmentin’ was embossed upon the one side of Beecham’s tablets, the Augmaxil tablets were blank.

[22] On whether the shape mark of the tablet was distinctive, the Court determined that it was not - either inherently or having been acquired. As to the latter, the Court acknowledged that because of the massive production of the Augmentin tablets, ‘the average pharmacist will probably recognise an Augmentin tablet as such.’14 However, no pharmacist would regard the shape alone as a guarantee that the tablet comes from Beecham. I understand the word ‘regard’ in the preceding sentence to signify ‘rely on’. Thus, the ‘recognition-association test’ was not considered adequate. Beecham was cited with approval by the Singapore Court of Appeal in Nestlé SA v Petra Foods Ltd,15 where the ‘recognition-association’ test was expressly rejected.16

[23] However, ‘the recognition-association test’ was adopted by this Court in Nestle v International Foodstuffs17 (Nestlé South Africa). The dispute was about Nestlé’s four-finger wafer and two-finger wafer shape mark held by Nestlé in the ‘Kit Kat’ chocolate bar, marketed and sold by it. Nestlé alleged that the physical shape, as well as the name of a chocolate bar marketed and sold by the respondent, Iffco, infringed its four-finger wafer shape mark in respect of the Kit Kat chocolate bar. Iffco, in turn sought the expungement of that mark.

[24] This Court held that Nestlé’s shape mark had acquired distinctiveness. It pointed to the fact that Nestlé had marketed and sold the Kit Kat chocolate bar in South Africa for 50 years and that extensive use had been made of its shape for promotion and advertising purposes.18 The Court accepted two consumer surveys presented by Nestlé, on the basis of which it concluded that the ordinary consumer was able to recognise the shape of the Kit Kat chocolate bar, and associate such shape with Nestlé and the Kit Kat brand.19 Consequently, Iffco was found to have infringed Nestlé’s four-finger wafer shape mark. (emphasis added.)

[25] Almost at the same time that Nestlé South Africa was decided, the trade mark battle in respect of Nestlé’s four-finger chocolate bar, was taking shape in the United Kingdom between Nestlé and Cadbury. In a trilogy of decisions – Nestlé SA v Cadbury UK (Nestlé UK I);20 Nestlé SA v Cadbury UK (Nestlé UK II),21 and Nestlé SA v Cadbury UK (Nestlé UK III)22 – the English courts firmly rejected the ‘recognition-association’ test. On almost similar facts presented in Nestlé South Africa, the English courts concluded that Nestlé’s four-finger shape mark had not acquired distinctiveness. This was despite the fact that: the four-finger Kit Kat was one of the most popular chocolate products on the market; products in the shape of the trade mark had been on the market for 75 years prior to the date of the application; substantial sums had been invested in promoting Kit Kat; and, in the survey, at least half of the respondents thought that the picture shown to them depicted a Kit Kat.23

[26] The brief background to the Nestlé trilogy is this. The Registrar of Trade Marks had refused to register the trade mark on the basis that it lacked distinctive character – inherent or acquired. In an appeal to it, the UK high court in Nestlé UK I held that in relation to acquired distinctiveness, it was necessary to seek a preliminary ruling from the Court of Justice of the European Union (the CJEU) in order to determine Nestlé’s appeal. It accordingly referred the following question to the CJEU:24

‘In order to establish that a trade mark has acquired distinctive character following the use that had been made of it . . ., is it sufficient for the applicant for registration to prove that at the relevant date a significant proportion of the relevant class of persons recognise the mark and associate it with the applicant’s goods in the sense that, if they were to consider who marketed goods bearing that mark, they would identify the applicant; or must the applicant prove that a significant proportion of the relevant class of persons rely upon the mark (as opposed to any other trade marks which may also be present) as indicating the origin of the goods?’

The UK high court offered its preliminary view that an applicant must show that a significant proportion of the relevant class of persons rely upon the trade mark (as opposed to any other trade marks which may also be present) as indicating the origin of the goods.25

[27] The CJEU subsequently delivered its judgment in Nestlé SA v Cadbury UK26 (the CJEU judgment) in which it considered the question referred to it. The CJEU reformulated the question, and after a survey of the authorities on acquired distinctiveness, it answered the (reformulated) question as follows:

‘. . . [i]n order to obtain registration of a trade mark which has acquired a distinctive character following the use which has been made of it . . . the trade mark applicant must prove that the relevant class of persons perceive the goods or services designated exclusively by the mark applied for, as opposed to any other mark which might also be present, as originating from a particular company.’27

[28] The matter reverted to the high court for determination. Arnold J, who had referred the matter to the CJEU lamented the fact that the CJEU had reformulated the question he had referred, and after referring to various ‘pointers’, he said:

‘Accordingly, I conclude that, in order to demonstrate that a sign has acquired distinctive character, the applicant or trade mark proprietor must prove that, at the relevant date, a significant proportion of the relevant class of persons perceives the relevant goods or services as originating from a particular undertaking because of the sign in question (as opposed to any other trade mark which may also be present).’28

[29] The high court applied the above test and concluded that Nestlé’s four-finger-shaped Kit-Kat chocolate bar had not acquired distinctiveness. The appeal to the England and Wales Court of Appeal turned on whether, on the facts, the test as established by the CJEU was correctly applied. Nestlé contended that the Registrar of Trade Marks and the high court had, instead, applied the reliance test, which according to Nestlé, was different from the ‘perception’ test formulated by the CJEU. Kitchin LJ, who wrote the main judgment,29 disagreed. He acknowledged that the CJEU had not used the term ‘reliance’ in its judgment. However, the court said, given the essential function of a trade mark, perception by consumers that goods or services designated by the mark originate from a particular undertaking, means they can rely upon the mark in making or confirming their transactional decisions. In this context, ‘reliance is a behavioural consequence of perception.’30 The appeal court went on to endorse the test formulated by the CJEU and adopted by Arnold J, referred to in paras 27 and 28 above.31

[30] The appeal court emphasised the inadequacy of the ‘recognition and association’ test to determine whether a mark has become distinctive by prior use. ‘[I]t is not sufficient for the trade mark owner to show that a significant proportion of the relevant class of persons recognise and associate the mark with the trade mark owner’s goods.’32 Kitchin LJ then said the following:

‘[T]o a non-trade mark lawyer, the distinction between, on the one hand, such recognition and association and, on the other hand, a perception that the goods designated by the mark originate from a particular undertaking may be a rather elusive one. Nevertheless, there is a distinction between the two . . . [which] is an important one.’33

Applying the ‘perception test’, it was found that Nestlé’s four-finger Kit-Kat chocolate bar had not acquired distinctiveness. Accordingly, the appeal was dismissed.

[31] This brings me to Tupperware’s shape mark. There is simply no evidence that the purchasers of the Eco bottle perceive the shape of the bottle to indicate that it originates from a particular source, let alone from Tupperware. A careful perusal of its promotional material shows that Tupperware at no time promoted, marketed or sold the Eco bottle with reference to its shape. It is always marketed with reference to the Tupperware trade mark, and as part of the Tupperware range of products. In other words, the reference is never to the shape of the Eco bottle as a trade mark, but to the Eco bottle as part of the Tupperware range of goods. Viewed in this light, it may well be that the apparent popularity of the Eco bottle is due to it being part of the popular Tupperware range of goods. That, more than its shape, seems to be the attractive force to the Eco bottle.

[32] And, as mentioned already, the Eco bottle is used in conjunction with the Tupperware trade mark, which is embossed on the side, though subdued and would not easily be visible from a distance. In other words, the relevant sector of the public might have come to perceive the Eco bottle bearing the mark as originating from Tupperware because of its well-known trade mark, and not because of the shape of the bottle. As pointed out by Floyd LJ in Nestlé UK III (at para 102) where a mark has been used in combination with other marks, the task of establishing acquired distinctiveness inevitably becomes more difficult.

[33] This is because it is necessary to isolate the perception of the mark applied for, and not other marks used in combination with it.34 Thus, the fact that Tupperware ensured that its logo is embossed on the Eco bottle, points to two possibilities: (a) a clear recognition that consumers did not rely upon the shape in the trade mark sense, and that they in fact relied upon the Tupperware trade mark; (b) that Tupperware did not trust the shape of its Eco bottle on its own to identify the trade source.

[34] In the end, the shape of the Eco bottle, to use the language in Beecham,35 ‘did not distinguish it from [water bottles] sold by others but, distinguishes them somewhat from other [water bottles].’ In addition, there were many water bottles on the market with the ‘identical or substantially identical shape, albeit not necessarily with the same size’ as the Eco bottle.

[35] The shape of the Eco bottle as a trade mark falters even on the low threshold ‘recognition and association’ test, or the reliance test. As is clear from the authorities, even if one accepts that a significant proportion of consumers in the water bottle sector recognise Tupperware’s Eco bottle and associate it with Tupperware, this would not be sufficient for the shape to denote the origin or authenticity of the bottle. As to the reliance test, there is no evidence that purchasers of the Eco bottle relied upon its shape to confirm its origin or authenticity. Tupperware’s Eco bottle is therefore not distinctive, and the high court was correct to uphold Buhle Brands’ counterclaim by ordering the cancellation of the registered mark. It is not necessary to consider Buhle Brands’ other trade mark challenges.

[36] I now turn to Tupperware’s passing off claim. Passing-off consists in a representation by one person that the goods or services marketed by him or her are from another or that there is an association between such goods or services and the business conducted by the other.36 There is a caveat. The law against passing-off is not designed to grant monopolies in successful get-ups. A certain measure of copying is permissible, provided that the imitator ‘makes it perfectly clear to the public that the articles which he is selling are not the other manufacturer’s, but his own articles, so that there is no probability of any ordinary purchaser being deceived.’37

[37] In passing off proceedings, the court must consider all extraneous factors in reaching a conclusion that confusion is likely. The entire get-up of the respective products is compared, including the shapes, the markings and the decorations on the products, as well as how the respective trade marks are applied to the products.

[38] In the present case, the shape of the Eco bottle is that of an hourglass. The bottle is manufactured from a transparent, or at least translucent, plastic material, and is available in a range of colours. The well-known ‘Tupperware’ trade mark is embossed in an almost inconspicuous manner on the upper side of the bottle, and the mark ‘Eco bottle’ is embossed on the lid. It includes a flip-top or screw-top, and may have a handle. The cap is made from solid plastic, which may or may not be the same colour as the bottle. Bohle’s bottle is also made from transparent or translucent plastics material with an hourglass shape, with a similar colour range as the Eco bottle. The words ‘Botle Buhle’ are embossed on the side of the bottle and on the cap in the same manner as on the Eco bottle. The resemblance between the two bottles is evident. The respective parties’ water bottles look like this:

Tupperware Eco bottles

Botle Buhle bottles

[39] There are three requirements for a successful passing off action. The first is proof of the relevant reputation.38 The second is that there is a reasonable likelihood that members of the public may be confused into believing that the business of one is, or is connected with, that of another.39 The third is damage. The requirements were usefully summarised in Pioneer Foods v Bothaville Milling40 as follows:

‘. . . [P]assing off occurs when A represents, whether or not deliberately or intentionally, that its business, goods or services are those of B or are associated therewith. It is established when there is a reasonable likelihood that members of the public in the marketplace looking for that type of business, goods or services may be confused into believing that the business, goods or services of A are those of B or are associated with those of B. The misrepresentation on which it depends involves deception of the public in regard to trade source or business connection and enables the offender to trade upon and benefit from the reputation of its competitor. Misrepresentations of this kind can be committed only in relation to a business that has established a reputation for itself or the goods and services it supplies in the market and thereby infringe upon the reputational element of the goodwill of that business. Accordingly proof of passing off requires proof of reputation, misrepresentation and damage. The latter two tend to go hand in hand, in that, if there is a likelihood of confusion or deception, there is usually a likelihood of damage flowing from that.’41

[40] The nature of the reputation that a claimant such as Tupperware has to establish was stated in Reckitt & Colman v Borden:42

‘[H]e must establish a goodwill or reputation attached to the goods or services which he supplies in the mind of the purchasing public by association with the identifying 'get-up' (whether it consists simply of a brand name or a trade description, or the individual features of labelling or packaging) under which his particular goods or services are offered to the public, such that the get-up is recognised by the public as distinctive specifically of the plaintiff’s goods or services.’43

[41] As to how the requisite reputation is to be established, that may be inferred from extensive sales and marketing,44 and may be proved by evidence regarding the manner and scale of the use of the get-up.45 In the present case, the high court found that Tupperware had established the necessary reputation in the Eco bottle, based on sales and marketing of the bottle. I am of the view that the high court was correct in this conclusion. The sales figures for the ECO bottle were substantial. Having been first sold in India in 2009, the Eco bottle quickly became one of Tupperware’s top-selling products.

[42] The undisputed figures provided by Tupperware show that over a period of four years between 2015 and 2018, the total sales figure in South Africa was R590 246 845. This shows exponential growth in total sales: R68 355 693 in 2015; R144 957 695 in 2016; R195 116 603 in 2017; and R181 816 854 in 2018. In addition, the high court considered that the Eco bottle had been promoted extensively on various platforms, including in Tupperware’s catalogues and newsletters. Hard copies of the promotional leaflet and catalogues are distributed to the authorised distributors on a monthly basis who then distribute them to the consultants.

[43] The high court considered that in view of Tupperware’s ‘substantial sales’ of the Eco bottle, it can be inferred that the get-up of the Eco bottle will be regarded by those members of the public who have attended a Tupperware party, especially those who have purchased an Eco bottle at such a party, as being distinctive of Tupperware’s goods. The high court therefore concluded that Tupperware had succeeded in proving the requirement of distinctiveness in the get-up as a whole. In my view, the high court’s reasoning and finding in this regard are unassailable and undoubtedly correct.

[44] Before I consider how the high court approached the issue of the likelihood of confusion, I refer briefly to the high court’s observation that Buhle Brands’ water bottle and the Eco bottle were ‘virtually identical.’ I share this view. This behoved Buhle Brands to make it clear to the public that its water bottle is not Tupperware’s, but its own. In this regard, the only significant difference between the competing bottles is the embossing of the words ‘Tupperware’ and ‘Botle Buhle’ on the side and on the cap of the respective bottles. But these, as mentioned already, are inconspicuous, and do little or nothing to distinguish the two products.

[45] In Weber-Stephen v Alrite Engineering46 this Court had to consider whether the respondent had complied with a court order to distinguish its virtually identical product from the appellant’s Weber One Touch Barbecue Grill, which the high court had found passed off as the appellant’s product. Its effort to distinguish was in the form of four large notices (two in English and two in Afrikaans) attached to the outside of the grill. The English notices read as follows: ‘This MIRAGE braai/oven is an all South African product by ALRITE and has NO CONNECTION WITH the “One Touch Barbecue Grill” of WEBER-STEPHENS CO of America.’ This Court held that the notice had done nothing effectively to eliminate the confusion created by the shape and configuration of the respondent's product, and accordingly found that the respondent had breached the interdict.

[46] The manner in which the names of the two traders are embossed on their products in the present case is directly opposite to what occurred in Schweppes Ltd v Gibbens.47 There two rival traders marketed soft drinks sold in similarly embossed bottles of very similar shape, design and colour scheme, and wording in a similar layout and font. However, the products respectively bore the distinctively different brand names ‘SCHWEPPES’ and ‘GIBBENS’ prominently on the label. The prominent display of the brand names was considered sufficient to distinguish between the products.

[47] As mentioned already, in the present case, Buhle Brand’s embossed name is inconspicuous and lacks the necessary prominence to distinguish its water bottle from the Eco bottle. My own impression, gleaned from the pictures in the record, is that of striking similarities between the Eco bottle and Buhle Brands’ bottle. It seems to me that the overall design of the Buhle Brands’ water bottle was not to distinguish it from that of Tupperware, but rather to associate the two. In other words, Buhle seems to have strained every nerve to associate its water bottle with the Eco bottle. The upshot of this is that the assessment of the likelihood of confusion should be undertaken on the footing that the two water bottles are virtually identical.

[48] I return to the high court’s consideration of the likelihood of confusion. It concluded that given the sales model, there was no likelihood of confusion. This is how the high court reasoned. The Eco bottles are not sold in retail stores but through a direct marketing strategy and sales model of ‘Tupperware parties.’ These ‘parties’ are organised by a Tupperware consultant who would invite potential customers into their homes to view the Tupperware product range. There are 32 authorised Tupperware distributors geographically spread throughout the country. The authorised distributorships buy the products directly from Tupperware and resell the products to the consultants, comprising 690 000 individuals. Buhle Brands conducts a similar sales model. Given the above, the high court reasoned:

‘The difficulty for [Tupperware] is that the sales model used by [it], which is also used by [Buhle Brands], excludes the possibility of confusion or deception. A consumer purchasing the respondent's water bottle at a party hosted by one of [Buhle Brands’] consultants, or just seeing it on [its] catalogue at such a party, will not be deceived into thinking that it is an ECO bottle marketed by [Tupperware]. She or he will know that it is a water bottle marketed by [Buhle Brands].’

[49] In my judgment, the high court erred in confining the enquiry into the likelihood of confusion and deception, to the Tupperware parties. It is correct that a member of the public who had attended such a party would have become aware that the Eco bottle is a Tupperware product. But this is not decisive, as suggested by the high court. The key issue is whether the relevant members of the public would likely make a business connection between the two traders in respect of their respective bottles. Where a potential customer encounters a consultant who sells both products, they may end up making an association between the two products. The consultant may even offer the consumer the Buhle Brands’ bottle because it is cheaper, instead of the Eco bottle.

[50] The high court also ignored the evidence that the two products are also marketed online by sales consultants, and that some of those consultants sell both Tupperware and Buhle Brands products. In some instances, they have the two catalogues depicted side by side. This, in my view, sows the seeds for the likelihood of confusion between the two products. Thus, a potential customer who had attended a Tupperware party may wish to purchase the Eco bottle online. They would search for it by name. Another potential customer may have seen the Eco bottle at the office, school or church. They would likely search for it by shape.

[51] In both instances, the potential customer would likely encounter the Eco bottle and the Buhle Brands bottle side by side. In either case, because of the similarities between the two products, they make the association between them. This association is even more likely to be made online with no one to explain the distinction between the two bottles. Because of the similarities, the consumer is likely to perceive the two bottles to be associated. This type of confusion, which results in consumers purchasing one product thinking that it is the one they know, or is associated with it, is at the heart of the action of passing-off. Therefore, the likelihood of confusion exists.

[52] To sum up, Tupperware has established that it had acquired goodwill deriving from the reputation it had built in respect of its Eco bottle since 2011. The reputation was such that potential customers who attended Tupperware parties identified the Eco bottle by its general get-up, and as being the product of Tupperware. Those customers would perceive the virtually identical water bottles as being of the same provenance. The similarities are such that a substantial number of consumers would likely create a connection between the two products. In addition, by adopting the same marketing strategy as Tupperware, Buhle Brands had sought to associate its product in every respect, with that of Tupperware. This would enable Buhle Brands to trade its water bottle upon and benefit from the reputation of Tupperware’s Eco bottle. The damage to Tupperware is inevitable. Accordingly, Tupperware’s passing-off application should have succeeded.

[53] There remains the issue of costs. Both parties have achieved some success on appeal. Buhle Brands has succeeded in its trade mark counter-application, and Tupperware in its passing-off claim. A fair costs order would be that each party bears its own costs.

[54] In the result I make the following order:

1 The appeal against the order of the high court upholding the first respondent’s counter-claim is dismissed with no order as to costs.

2 The appeal against the order of the high court dismissing the appellants’ claim based on passing-off is upheld with no order as to costs.

3 The order of the high court is set aside and replaced with the following order:

‘1 The applicants’ application in respect of trade mark infringement is dismissed;

2 The respondent’s counter-application for the cancellation of the trade mark registered in the name of the first applicant, succeeds.

3 It is ordered that the South African trade mark no. 2015/25572 is to be cancelled in the Register of Trade Marks;

4 The applicants’ claim based on passing-off succeeds.

5 The respondent is restrained and interdicted from passing off its water bottle as being the first applicant’s Eco bottle, and/or part of the Eco bottle range and/or as being connected with the first applicant’s Eco bottle by making use of its water bottle or any other bottle shape confusingly similar to the first applicant’s Eco bottle.

6 Each party shall pay its own costs.’

__________________

T MAKGOKA

JUDGE OF APPEAL

APPEARANCES:

For appellants: P Ginsburg SC (with him LG Kilmartin)

Instructed by: Adams & Adams, Cape Town

Honey Attorneys, Bloemfontein

For first respondent: G Marriott

Instructed by: Bouwers Inc., Johannesburg

Hill, McHardy & Herbst Inc., Bloemfontein.

1 Beecham Group plc and Another v Triomed (Pty) Limited [2002] ZASCA 109; [2002] 4 All SA 193 (SCA) (Beecham) para 20.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 G C Webster et al Webster and Page: South African Law of Trade Marks (Service Issue 19, 2015) at 3-48(7) para 3.40.2.

5 Scandecor Developments AB v Scandecor Marketing AV & Others [2001] UKHL 21, [2002] FSR 122 (HL), cited with approval in AM Moolla Group Ltd and Others v Gap Inc and Others [2005] ZASCA 72; [2005] 4 All SA 245 (SCA) para 38.

6 Bergkelder Bpk v Vredendal Koöp Wynmakery and Others [2006] ZASCA 5; 2006 (4) SA 275 (SCA); [2006] 4 All SA 215 (SCA).

7 Ibid para 7 (footnote excluded).

8 Ibid.

9 Bergkelder para 8, citing Bongrain SA’s Trade Mark Application [2005] RPC 14 para 26.

10 Ibid para 9.

11 The London Taxi Corporation Ltd (t/a the London Taxi Company) v Frazer-Nash Research Ltd & Anor [2017] EWCA Civ 1729 para 45.

12 M Tsele Shape Up or Ship Out! — On Establishing That a Shape Has ‘Acquired Distinctiveness’ for Trade Mark Purposes (2020) 137 SALJ 528.

13 Ibid 535-536.

14 Beecham para 24 (emphasis added.)

15 Société des Produits Nestlé SA v Petra Foods Ltd [2016] SGCA 64.

16 Ibid para 45.

17 Societe Des Produits Nestle SA and Another v International Foodstuffs Co and Others [2014] ZASCA 187; [2015] 1 All SA 492 (SCA) (Nestle South Africa).

18 Ibid para 13.

19 Ibid para 14.

20 Société des Produits Nestlé SA v Cadbury UK Ltd [2014] EWHC 16 (Ch).

21 Société des Produits Nestlé SA v Cadbury UK Ltd [2015] ETMR 50.

22 Société des Produits Nestlé SA v Cadbury UK Ltd [2017] EWCA Civ 358.

23 Nestlé UK III para 29.

24 Member states of the European Union may refer questions of law to the CJEU. In terms of Article 256(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union the decisions of the CJEU are binding on European Union (EU) member states only as regards the questions of law posed. Likewise, Article 58 of Protocol (No 3) on the Statute of the Court of Justice of the European Union provides that appeals from the General Court to the CJEU shall be limited to points of law. Courts in member states must still adjudicate factual disputes. At the time when the Nestlé cases were decided, the United Kingdom was still a member of the EU.

25 This Court in Nestlé South Africa (at para 33) declined to follow the preliminary view expressed by the UK high court on the basis that ‘[t]he views do not constitute findings of the court’ and did not ‘require further consideration.’

26 Société des Produits Nestlé SA v Cadbury UK Ltd Case C-215/14 [2015] ETMR 50.

27 Ibid para 67.

28 Nestlé UK II para 57.

29 Sir Geoffrey Vos Ch and Floyd LJ concurred and wrote concurring in separate judgments.

30 Nestlé UK III para 82.

31 Ibid para 84.

32 Ibid para 77 (emphasis added.)

33 Ibid.

34 Ibid para 102.

35 Beecham para 24.

36 Capital Estate and General Agencies (Pty) Ltd and Others v Holiday Inns Inc and Others 1977 (2) SA 916 (A) at 929C-E; Williams t/a Jenifer Williams & Associates and Another v Life Line Southern Transvaal 1996 (3) SA 408 (A) at 418F-H (Williams).

37 Pasquali Cigarette Co Ltd v Diaconicolas & Capsopolus 1905 TS 472 at 479.

38 Hoechst Pharmaceuticals (Pty) Ltd v The Beauty Box View Parallel Citation (Pty) Ltd (in liquidation) and Another 1987 (2) SA 600 (A) 613FG; Brian Boswell Circus (Pty) Ltd and another v Boswell Wilkie Circus (Pty) Ltd 1985 (4) SA 466 (A) 479D.

39 Williams 418H.

40 Pioneer Foods (Pty) Ltd v Bothaville Milling (Pty) Ltd [2014] ZASCA 6; [2014] 2 All SA 282 (SCA).

41 Ibid para 7.

42 Reckitt & Colman Products Ltd v Borden Inc and Others [1990] RPC 341 (HL) 406.

43 Ibid lines 26-31 and referred to with approval in Caterham Car Sales and Coachworks Ltd v Birkin Cars (Pty) Ltd and Another [1998] ZASCA 44; 1998 (3) SA 938 (SCA); paras 21 and 22.

44 Hollywood Curl (Pty) Ltd and Another v Twins Products (Pty) Ltd 1989 (1) SA 236 (A) at 249J; Adidas AG and Another v Pepkor Retail Limited [2013] ZASCA 3 para 29.

45 Adidas AG fn 5 para 29.

46 Weber-Stephen Products Co v Alrite Engineering (Pty) Ltd 1992 (2) SA 489 (A).

47 Schweppes Ltd v Gibbens (1905) 22 RPC 601 HL.

Cited documents 6

Judgment 6

- AM Moolla Group Ltd and Others v Gap Inc and Others (123/2004) [2005] ZASCA 72 (9 September 2005)

- Adidas AG and Another v Pepkor Retail Ltd (187/2012) [2013] ZASCA 3 (28 February 2013)

- Beecham Group Plc and Others v Triomed (Pty) Ltd (100/2001) [2002] ZASCA 109 (19 September 2002)

- Bergkelder Bpk v Vredendal Koöp Wynmakery and Others (105/2005) [2006] ZASCA 5 (9 Maart 2006)

- Caterham Car Sales and Coachworks Ltd v Birkin Cars (Pty) Ltd and Another (393/1995) [1998] ZASCA 44 (27 May 1998)

- Societe Des Produits Nestle SA and Another v International Foodstuffs Co and Others (100/2014) [2014] ZASCA 187 (27 November 2014)