Page | 17

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA

IN THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA,

GAUTENG DIVISION, PRETORIA

CASE NO.: 29067/2022

(1) REPORTABLE: YES / NO (2) OF INTEREST TO OTHER JUDGES: YES/NO (3) REVISED. ………………………... ………………………... DATE SIGNATURE

In the matter between:

MTHEMBU NTETHELELO Plaintiff

and

ROAD ACCIDENT FUND Defendant

JUDGMENT

INTRODUCTION

[1] This is a damages action relating to injuries sustained by the plaintiff, who was a pedestrian when he was run down by a motor vehicle on 13 June 2020. At the time, the plaintiff was a first-year student at the University of Johannesburg, studying towards a Diploma in Public Relations and Communications. He discontinued his studies after the collision. The collision happened during the June recess and at the time, he had written the first semester examinations and completed four modules: Media, Communication Management, Public Relations, and Professional Writing Skills.

[2] The plaintiff reportedly suffered immediate loss of consciousness when he was hit by the insured vehicle. He sustained a Grade 3 concussion as a subset of mild head injury with neuropsychological fallout, scalp lacerations and bruises to his right knee. He continues to suffer the discomfort of chronic pain from the right knee and complains about intermittent frontal headaches, poor memory, and concentration difficulties.

[3] Following the collision, the plaintiff was admitted to the Charles Johnson Memorial Hospital, where he received hospital and medical treatment. He received analgesia, anti-tetanus toxoid injections, and his wounds were cleaned, sutured, and dressed. X-rays were taken. He was discharged the same day.

[4] The plaintiff lodged a claim with the defendant (“the RAF") in terms of the provisions of the Road Accident Fund Act, No. 56 of 1996 (“the Act”) claiming damages resulting from the injuries sustained in the collision.

[5] There is no evidence that the RAF raised an objection to the claim, and the plaintiff later issued summons against it. Summons was duly served on the RAF, but it failed to file a notice of intention to defend. The action then found its way to this Court, sitting as the Default Judgment Trial Court and was set down to be heard on 10 April 2024. After hearing argument, the matter stood down to 11 April 2024 to hear the evidence of the plaintiff.

[6] When the matter was called, there was no appearance for the RAF, despite due notice of the trial date being given to it. The matter proceeded on a default basis.

[7] Counsel for the plaintiff proceeded to present his case in respect of all issues of liability and quantum [excluding the claim for general damages, for reasons set out later].

[8] After hearing the evidence of the plaintiff and argument by counsel, I reserved judgment.

LIABILITY

[9] The plaintiff bears the onus to prove that the RAF is liable under the provisions of the Act, to compensate him for damages suffered because of the injuries sustained in the collision. This includes the onus to prove that the driver of the insured vehicle negligently caused the collision.

[10] The plaintiff was the only witness who testified. In short, the plaintiff testified that he was walking on the shoulder of the road, with a friend, where one would ordinarily not expect vehicles to travel. He was facing oncoming traffic. The insured vehicle, that approached from the front, then somehow moved over towards the plaintiff, and collided with him, where he was still walking on the shoulder of the road.

[11] He testified that he could not avoid the collision. As a result, he suffered bodily injuries. He confirmed the date and place of the collision as pleaded in the particulars of claim. The hospital records referred to by some of the experts also confirm that the plaintiff was involved in the collision and that he was injured as a result.

[12] I am satisfied that the plaintiff established negligence on the part of the insured driver. His evidence proves at least one of the grounds of negligence as pleaded in the particulars of claim. It is obvious that the insured driver did not keep a proper lookout. If this was done, the collision would not have occurred. There is no suggestion that the plaintiff sustained injuries because of some other event. The collision is the sole and direct cause of his injuries.

[13] Because the defendant is in default and did not enter appearance to defend the action, there is no version of the insured driver, or a pleaded case that the plaintiff negligently caused or contributed to the collision. It is for the defendant to allege and prove contributory negligence on the part of the plaintiff.

[14] I am also satisfied that the plaintiff substantially complied with the provisions of the Act in lodging his claim and later instituting this action.

[15] In the circumstances, I find that the defendant is liable for 100% of the damages suffered by the plaintiff that may be causally linked to the collision.

THE DEFAULT JUDGMENT APPLICATION

[16] Application was made in terms of Rule 38(2) of the Uniform Rules of Court that I hear evidence on affidavit, as it would be expedient to do so. The affidavits deposed to by all the expert witnesses are filed on record.

[17] Havenga v Parker 1993 (3) SA 724 (T), confirmed by the Supreme Court of Appeal in Madibeng Local Municipality v Public Investment Corporation 2018 (6) SA 55 (SCA), found it is permissible to place expert evidence before the Court by way of affidavits in terms of Rule 38(2). Accordingly, that application was granted.

[18] The plaintiff substantially complied with the requirements set out in the Practice Directives of this Court and the Uniform Rules of Court, entitling him to proceed on a default basis.

[19] The plaintiff is claiming general damages and filed the required RAF4 forms in support thereof. However, there is no indication that the RAF formed a view on the seriousness of the injuries sustained by the plaintiff.

[20] Counsel for the plaintiff conceded that the decision whether the injuries of the plaintiff are serious enough to meet the threshold requirement for an award of general damages, was conferred on the RAF and not on the Court. The assessment of damages as “serious” is determined administratively in terms of the manner prescribed by the RAF Regulations, 2008, and not by the Courts. Accordingly, the plaintiff’s claim for general damages will be separated from the other heads of damages and postponed.

[21] The only remaining issue to be determined is the claim for loss of earnings. The plaintiff presented this claim as a direct loss of earnings, on the basis that the injuries sustained rendered him totally unemployable.

[22] I had regard to all the evidence filed on record. What follows is a summary of the evidence in respect of the plaintiff’s claim for loss of earnings.

The plaintiff’s education and employment history

[23] The plaintiff currently 23 years old and is his highest qualification is Grade 12 that he obtained in December 2019. He passed Grade 12 with admission to further his studies at a tertiary institution. Proof of this is filed on record. The plaintiff then enrolled for Diploma studies at the University of Johannesburg. Proof of this is also filed on record. He completed the first semester. The results obtained for the modules he attended during the first semester were, however, not filed on record.

[24] Following the collision, the plaintiff returned to university, but after about two months decided to quit. He has since not returned to university and is not employed. There is no evidence that the plaintiff failed any test or examination in any subject once he returned to university.

[25] There is no evidence that the plaintiff made any attempt to seek employment. Or, for that matter, that he was unsuccessful in his endeavors to do so.

[26] He has no employment history, following the collision.

The impact of the injuries on the plaintiff’s future education and employment

[27] The expert evidence and hospital records proves that the plaintiff sustained the following injuries as a direct result of the collision:

27.1. A Grade 3 concussion as a subset of mild head injury with some neuropsychological fallout.

27.2. Post-traumatic stress disorder and depression.

27.3. Scalp lacerations, and

27.4. Blunt trauma to his right knee.

[28] The orthopedic surgeon, Dr Tladi, reports that the plaintiff reported intermitted pain in the right knee. This is exacerbated by prolonged walking. Physical examination of the right knee revealed small scars. X-rays of the right knee were normal. The plaintiff still has normal ranges of movement of the right knee, all ligaments are intact, and there is no deformity or atrophy. Dr Tladi concludes with an opinion that the plaintiff “may later develop post traumatic osteoarthritis of the knee joint that may progress to warrant knee replacement that may need revisions due to implants failure. The life span of knee replacement is between 10-15 years.” Dr Tladi deferred to an occupational therapist and industrial psychologist for discussion about the plaintiff’s future work capacity, future employability and earning capacity.

[29] The neurosurgeon, Dr Mosadi, confirmed that the plaintiff sustained a concussive type head injury with reported loss of consciousness. When the plaintiff was admitted to hospital, his GCS was 15/15. On examination, there was no injury to the plaintiff’s spine. There is no neurophysical fallout. The plaintiff’s motor system and nervous system remains intact. He now suffers from post-concussion headaches. Dr Mosadi deferred to other experts to determine the consequences of the concussion.

[30] The clinical psychologist and neuropsychologist concluded their report by stating that the plaintiff’s cognitive functioning may have been slightly affected by the collision. This indicates that he may still cope academically with support, even though his moderate psychological functioning could have interfered with his “less cognitive functioning”. These conclusions were made, also considering that the plaintiff now presents with depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. According to the neuropsychologist, the plaintiff’s cognitive functioning “may have been slightly affected” by the injuries sustained in the collision.

[31] The educational psychologist concluded that pre-collision, the plaintiff would have been able to complete his qualification [with reference to the diploma studies]. Now, having regard to the injuries sustained in the collision, however:” It can thus be concluded that Mr Mthembu's academic performance may have been immensely impacted by the accident under review. He may not be able to complete his diploma. His ability to learn appears to have been affected by the accident under discussion”. This conclusion is mainly based on the diagnosis of PTSD and poor concentration now experienced by the plaintiff.

[32] The occupational therapist, R. Mashudu reports that the plaintiff retained residual physical capacity for low range heavy work category. Further:” Additionally, due to experienced pain within the right knee, Mr. Mthembu has been rendered an unfair competitor within the medium work category and will have to rely on sympathetic accommodations in order to productively complete work tasks. Should he develop the envisaged right knee post-traumatic arthritis, his work parameters will be further narrowed. At the time, he will be suited for sedentary and occasional light work category, with increased need for reasonable accommodations”.

[33] The industrial psychologist, T Kalanko, had regard to all expert reports and formed the opinion that:” The writer highlights that, he has not been to secure any form of employment since this accident. It is highly likely that Mr. Mthembu may be prone to extended periods of unemployment in the open labour market as currently the case, and consequently remain unemployed for the remainder of his life”. The plaintiff apparently discontinued his diploma studies because he experienced difficulties coping with his academic demands due to the sequalae of the injuries sustained in the collision. The case is thus based on the plaintiff being totally unemployable.

LAW ON EXPERT EVIDENCE AND LOSS OF EARNINGS

[34] Meyer AJ (as he then was) held in Mathebula v RAF (05967/05) [2006] ZAGPHC 261 (8 November 2006) at para [13]:

“An expert is not entitled, any more than any other witness, to give hearsay evidence as to any fact, and all facts on which the expert witness relies must ordinarily be established during the trial, except those facts which the expert draws as a conclusion by reason of his or her expertise from other facts which have been admitted by the other party or established by admissible evidence. (See: Coopers (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd v Deutsche Gesellschaft für Schädlingsbekämpfung MBH, 1976 (3) SA 352 (A) at p 371G; Reckitt & Colman SA (Pty) Ltd v S C Johnson & Son SA (Pty) Ltd 1993 (2) SA 307 (A) at p 315E); Lornadawn Investments (Pty) Ltd v Minister van Landbou 1977 (3) SA 618 (T) at p 623; and Holtzhauzen v Roodt 1997 (4) SA 766 (W) at 772I).”

[35] In Michael and Another v Linksfield Park Clinic (Pty)Ltd and Another (2002) 1 All SA 384 (A), the Supreme Court of Appeal had the following to say regarding the approach to be adopted in dealing with the expert evidence:

"[34] . . . . . . . As a rule, that determination will not involve considerations of credibility but rather the examination of the opinions and the analysis of their essential reasoning, preparatory to the court's reaching its conclusion on the issues raised."

[36] That being so, what is required in the evaluation of such evidence is to determine whether and to what extent their opinions advanced are founded on logical reasoning. . . .”

[36] In Twine and Another v Naidoo and Another (38940/14) [2017] ZAGPJHC 288; [2018] 1All SA 297 (GJ), the court had the following as a guide in approaching the expert evidence:

“Para 18: a. The admission of expert evidence should be guarded as it is open to abuse, c. The expert testimony should only be introduced if it is relevant and reliable. Otherwise, it is inadmissible. ." r. A court is not bound by, nor obliged to accept, the evidence of an expert witness: "It is for (the presiding officer) to base his findings upon opinions properly brought forward and based upon foundations which justified the formation of the opinion." s. The court should actively evaluate the evidence. The cogency of the evidence should be weighed "in the contextual matrix of the case with which (the Court) is seized. If there are competing experts, it can reject the evidence of both experts and should do so where appropriate. The principle applies even where the court is presented with the evidence of only one expert witness on a disputed fact. There is no need for the court to be presented with the competing opinions of more than one expert witness in order to reject the evidence of that witness. 2023 JDR 1213 p11 t.”

[37] It is trite that the plaintiff bears the onus to prove how the injuries have affected him in respect of his earning capacity.

[38] There is a difference between the question whether the plaintiff has suffered an impairment of earning capacity, and the question whether the plaintiff will in fact suffer a loss of income in the future.

[39] The latter question is one of assessment in respect of which there is no onus in the traditional sense. It involves the exercise of quantifying as best one can the chance of the loss occurring.

[40] It is now trite that any enquiry into damages for loss of earning capacity is by nature speculative. All the court can do is estimate the present value of the loss whilst it is helpful to take note of the actuarial calculations, a court still has the discretion to award what it considers right.

APPLYING THE FACTS TO THE LAW

[41] The experts all conclude that the plaintiff is not the person that he used to be. He has been compromised by the injuries sustained in the collision. The plaintiff has discharged the onus on a balance of probabilities, proving that he suffered an impairment of earning capacity.

[42] However, I am not convinced that the plaintiff has been rendered totally unemployable. He certainly retained not only the capacity to work but also the capacity to study (be it with difficulty). All in all, he has been slightly compromised by the injuries sustained.

[43] The orthopedic surgeon does not provide any factual or statistical basis why it should be accepted that the plaintiff may, in future, “develop post traumatic osteoarthritis of the knee joint that may progress to warrant knee replacement that may need revisions due to implants failure”. The basis for his opinion is not provided. Absent a reasonable basis, I cannot find that the aforesaid opinion is founded in logical reasoning. This is an important issue, as all the other relevant experts rely on this future knee replacement to conclude that the plaintiff is now totally unemployable. Nobody knows if and when this knee replacement will be required. Significantly, current testing and examination by the orthopedic surgeon, show that the plaintiff’s knee function is normal.

[44] The psychologists say that the plaintiff is only slightly compromised and may well still be able to study. Further, that the plaintiff’s cognitive functioning “may have been slightly affected”. The educational psychologist did not consider the results obtained by the plaintiff during his first semester of studies. This is relevant to the postulation that the plaintiff would have obtained his diploma, was it not for the collision. There is a clear contradiction between the opinion of the educational psychologist and the psychologists: the former holds the opinion that the plaintiff will not cope with studies, and the latter, that the plaintiff will be able to study and is has only been slightly affected by the injuries. The educational psychologist did not adequately address this in the report. There is also no evidence as to what percentage of students progress from the first to second year and from second to third year. This has bearing on the period over which the undermentioned actuarial calculation has been made.

[45] The industrial psychologist did not adequately consider any other form of employment for which the plaintiff may be suited for, or any other form of tertiary education that may be pursued. The witness failed to adequately consider the possibility that the plaintiff may enter the informal sector, or pursue a trade qualification, for instance. The doomsday scenario is preferred without recognizing or even considering other possible outcomes. Long periods of unemployment are postulated, without any factual basis. No reference was made to studies or statistics that would support this opinion. The industrial psychologist did not interrogate the reasons why the plaintiff is still unemployed or any attempts made by him to secure employment.

[46] I am not bound by the opinions of the various experts regarding the plaintiff’s future loss of earnings. I am not persuaded that the injuries left the plaintiff totally unemployable, and therefore do not accept the opinions that promote such a case.

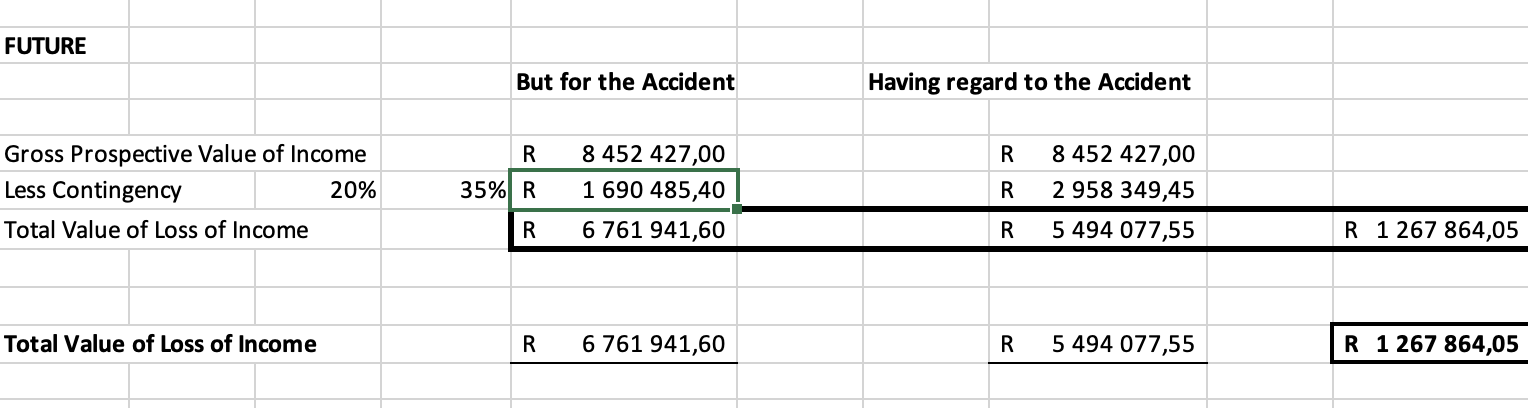

[47] An actuarial calculation was filed on record, based on the assumption that the plaintiff has been rendered unemployable. Without the application of contingencies, the calculated loss of earnings amounts to R8 452 427,00.

[48] For purposes of quantifying the plaintiff’s loss of earnings, I will accept that his pre-and post-collision earnings will be the same [R8 452 427,00]. This is done as the plaintiff failed to provide any alternative method to determine the loss. I must do the best I can with available evidence to come to a just award.

[49] With reference to the actuarial calculation, the correct contingency to be applied to the uninjured scenario, in my view, is 20%. Having regard to the facts of the matter, I accept that the plaintiff still retains the ability to study and to be gainfully employed in the open labour market, albeit with some difficulty. But then one must account for the fact that the plaintiff’s earning ability has been compromised. To provide for the loss of earning ability, I am of the view that a contingency deduction of 35% should be applied to his injured earnings.

[50] In accordance with section 17 (4A) (a) of the Act, for collisions on or after 1 August 2008, a claim for loss of income may not exceed a Gazetted amount ('the Cap') on an annual basis. The actuary confirmed in his report that the Cap does not apply in this matter. It will thus not be necessary for the actuary to prepare a new calculation, applying the aforesaid contingencies.

[51] By application of the aforesaid contingencies, the loss of earnings amounts to R1 267 864,05, as follows:

[52] I issue the following order:

52.1. The Defendant shall pay to the plaintiff the amount of R1 267 864,05 in respect of the claim for loss of earnings.

52.2. The amount of R1 267 864,05 shall be paid to the plaintiff within 180 (ONE HUNDRED AND EIGHTY) Court days of the date of this Court Order.

52.3. In the event of the aforesaid amount not being paid timeously, the defendant shall be liable for interest on the amount a tempore morae, calculated 14 (FOURTEEN) days after the date of this Order to date of payment, as set out in Section 17(3)(a) of the Road Accident Fund Act 56 of 1996.

52.4. The claim for general damages is separated from all other issues of quantum, and is postponed sine die.

52.5. The defendant shall pay the plaintiff’s taxed or agreed party and party costs on the High Court scale C, including the costs of and consequent to the employment of Counsel on trial for 10 and 11 April 2024, and the reasonable costs of expert reports delivered, within the discretion of the taxing master.

52.6. The amounts referred to above will be paid to the plaintiff’s attorneys, MASHAMBA ATTORNEYS, by direct transfer into their trust account, details of which are the following:

BANK NAME: ABSA BANK

ACCOUNT NAM: MASHAMBA ATTORNEYS

ACCOUNT NUMBER: 407-358-4708

BRANCH: PRETORIA

BRANCH CODE: 632 005

51.7 The Defendant shall issue an undertaking in terms of Section 17 (4) (a) of the Road Accident Fund Act as amended.

51.8 The Plaintiff shall allow the Defendants 180 days to make payment of the taxed costs from date of settlement or taxation thereof.

JM KILIAN

Acting Judge

High Court of South Africa

Gauteng Division, Pretoria

For the plaintiff:

Adv LB MAPHELELA

Instructed by:

MASHAMBA ATTORNEYS

For the defendant:

No appearance

Date of hearing: 10 and 11 April 2024

Date of Judgment: 23 April 2024