Editorial note: Certain information has been redacted from this judgment in compliance with the law.

IN THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA

(EASTERN CAPE LOCAL DIVISION, PORT ELIZABETH)

Case Number: 3429/2013

In the matter between:

A K Plaintiff

and

MINISTER OF SAFETY AND SECURITY First Defendant

RONALD KOLL Second Defendant

MATABATA MADUBEDUBE Third Defendant

ADINE SOLOMAN Fourth Defendant

JUDGMENT

SEPHTON AJ:

INTRODUCTION

This is an action against the Minister of Police for alleged negligence on the part of his employees. This is also an action against certain named member of the South African Police Services for their alleged negligence.

The plaintiff is an adult female businesswoman who grew up in Port Elizabeth but was living in Johannesburg. The first defendant is the Minister of Safety and Security. The remaining defendants are employees of the first defendant, sued in their personal capacity. I will hereinafter refer to the defendants collectively as the “SAPS” except where it is necessary to deal with them individually.

The plaintiff instituted this action for damages against the defendants as a result of an incident which took place on 9 to 10 December 2010 and what followed thereafter.

The plaintiff was in the Eastern Cape for business purposes in December 2010 but also used the opportunity to finalise the purchase of a house for her mother. Having a few hours to spare before flying back to Johannesburg, she decided to take advantage of the perfect weather conditions and go for a walk on Kings Beach. She parked her car in the Kings Beach parking lot at about 2pm. The plaintiff was due to return to her mother’s home prior to her departure back to Johannesburg to collect her friend who would go with her to the airport.

The plaintiff set off along the beach in an Easterly direction. In broad daylight she was assaulted, robbed of her personal belongings and dragged into the bushes which abut the inland side of the beach by an unknown man. The man instructed her to walk with him to the sand dunes. In desperate fear of her life, she complied.

The plaintiff’s life was spared but at a price. When they got to the dunes, the assailant instructed her to take off her clothes, blind-folded her with them and raped her. For the rest of the afternoon, she was consistently raped. At the time, she thought it was the same man who was simply changing his pants between the rapes; later she came to believe that it had been more than one assailant and that she had in fact been gang-raped.

At around sunset the original assailant returned. The plaintiff knew this because he spoke to her and she recognised his voice. He remained for the rest of the night throughout which he continued to rape her. And he continued to threaten her life. She remembered things she had read about other women who had survived similar ordeals. She decided to do whatever she needed to do to survive. She engaged him in conversation in the hopes of dissuading him from raping her further and in the hopes of dissuading him from killing her.

Although there was initially some doubt about whether there was one or more assailant, nothing turns on this as the parties agree that regardless of whether there was one or more assailant, the plaintiff endured an extremely traumatic event at the hands of one or more persons. During the trial the assault, abduction, subsequent captivity and rape was referred to by both parties as “the traumatic incident”.

The plaintiff managed to escape from her abductor(s) in the early hours of 10 December 2010 and sought the assistance of a group of men who were out for an early morning jog. She was escorted back to King’s Beach parking lot and then to the Humewood police station by Mr Britz, one of the joggers. Altogether, she had been held captive in the sand dunes and consistently raped over a period of approximately fifteen hours.

When the plaintiff failed to return home to collect her friend who would accompany her to the airport, and missed her flight she was reported missing by a Mr Majwa a member of her extended family. An alert went out from the SAPS Radio Control Room, 10111.

At approximately 23h30, the plaintiff’s car was found at the King’s Beach car park by members of the Humewood SAPS. It had been broken into.

The relevant police units were activated and the investigation into the incident commenced.

According to the defendant a search (a ground search with a dog and later a helicopter search) commenced in the immediate area. The plaintiff does not dispute that the ground and air searches took place but disputes that the search took place in the entirety of the relevant area.

The plaintiff was not found, despite a search which lasted some three hours.

In the course of the investigation, which remained active for more than two years, some arrests were made, but the suspects were eventually cleared by DNA evidence. One suspect (“Jakavula”) who was arrested on the day after the plaintiff was found, was convicted of theft of the plaintiff’s personal belongings from her vehicle. However, in respect of the rape, no-one was ultimately tried and there were consequently no convictions. The plaintiff’s abductor and rapist/s have to this day not been found.

The plaintiff’s action for damages against the defendants is based on the alleged negligence of the defendants in respect of both the search for her on the night of 9 and 10 December 2010 and the subsequent investigation. This action was launched in November 2013.

Evidence was led over a 5-week period, commencing in February 2018 and resuming in July 2018 with the parties presenting their final arguments on 15 August 2018.

The plaintiff alleged that SAPS wrongfully and negligently breached its duty to investigate the crimes committed against the plaintiff; alternatively, if they did so investigate, they failed to do so with the skill, care and diligence required of reasonable police officers. As a result of this the plaintiff contended that the SAPS have caused her psychological injury and are liable to pay her damages.

Expert evidence was led which showed that the traumatic incident has had a debilitating effect on the plaintiff and that every aspect of her life has been changed by it. It is not in dispute that because of the traumatic incident, the plaintiff has suffered a severe and enduring psychological injury. It is also not in dispute that because of the perceived or actual paucity of the investigation and delay in finalising the investigation and bringing the perpetrator(s) to book, the plaintiff’s psychological injuries have been exacerbated.

THE GENERAL CONSTITUTIONAL OBLIGATIONS OF SAPS AND THEIR RELATIONSHIP WITH THE PUBLIC

Before proceeding to the specifics of the claim, it is pertinent to note that what happened to plaintiff is an all too common occurrence in South Africa, and especially in the Eastern Cape. South Africa is a country of great beauty with a mild climate that lends itself to recreational and sporting outdoor activity, both of which contribute to mental and physical health. Large numbers of the population avail themselves of this opportunity, especially in the Eastern Cape’s coastal cities.

The threat of sexual violence to women is indeed as pernicious as sexual violence itself. It is said to go to the very core of the subordination of women in society. It entrenches patriarchy as it imperils the freedom and self-determination of women. It is deeply sad and unacceptable that few women or girls dare to venture into public spaces alone, especially when it is dark and deserted.1

According to a Statistics South Africa report released in June 2018, the rape of South African women is among the highest in the world. The report shows that “a total of 250 out of every 100 000 women were victims of sexual offence, compared to 120 out of every 100 000 men”. Using the 2016-17 South African Police Service statistics, in which 80% of the reported sexual offences were rape, together with Stats SA’s estimate that 68.5% of the sexual offences victims were women, it can be estimated that the number of women raped is 138 per 100 000. This figure is among the highest in the world.2

The number of women who experienced sexual offences also jumped from 31 665 in 2015-16 to 70 813 in 2016-17 – an increase of 53%. “These are drastic increases in less than 24 months,” the report said.3 One of the sad things about these figures is that the situation is almost definitely worse than the statistics show. The respected journal “The Economist” recently estimated that one in every nine rape cases go unreported, which means that someone in South Africa is being raped every 2 minutes.4

Our Constitution, national legislation, formations of civil society and communities across our country have all set their faces firmly against this horrendous invasion and indignity imposed on our women and girl-children. It is to these civil society organisations that the plaintiff turned, seeking assistance in trying to get her case properly investigated and have the perpetrator(s) convicted. It follows that the state, through its foremost agency against crime, the police service, bears the primary responsibility to protect women and children against this prevalent plague of violent crimes.5

These are rights that the state is under a constitutional obligation to respect, protect, promote and fulfil (Section 7(2) of the Constitution.) A vital mechanism through which this is to be done is the police service.6

THE PRESENT CASE

In order to succeed, the plaintiff has the burden of proving the facts in support of her claim, namely actions/omissions on behalf of the defendants and that such actions/omissions:

were wrongful;

were negligent;

caused the damage (“damnum”) suffered by the plaintiff; and

that such damage (in the instant matter psychiatric illness or psychopathology) in turn gave rise to her entitlement to a claim for damages.

PRELIMINARY PROCEDURAL MATTER – SEPARATION OF ISSUES

Initially plaintiff brought an application to separate the issues so that the elements of unlawfulness, wrongfulness and negligence were decided prior to the issues of causation and damages. This application was brought in terms of rule 33(4) and opposed by the defendants. At the same time the defendants brought an application to postpone the trial which was due to commence on Monday 19 February 2018. This was opposed. After hearing argument on 6 February 2018, Mageza AJ granted judgment in favour of the plaintiff and the issues were separated accordingly. SAPS application for a postponement was dismissed with costs. The costs of this application were awarded to the plaintiff.

At the commencement of the trial I did not reconsider whether it was appropriate to separate the issues as requested and the trial commenced on the basis of the order granted by Mageza AJ.

When the proceedings resumed on 16 July 2018 I was advised that the parties had revisited the separation of the issues as decided by Mageza AJ and had concluded it would be more convenient for the trial court to decide the issues of negligence and causation but not quantum. Clearly having commenced the trial and then having an opportunity to carefully consider the course of the litigation as a whole, the parties agreed that the issues should not have been separated.

Having considered the evidence which needed to be led by both parties to prove and disprove the factual issues at stake, I concluded that this would indeed be the most appropriate manner of dealing with the trial and made an order to this effect. The parties did not agree on how to deal with the costs of the separation application and postponement application which were awarded to the plaintiff. This issue was left for argument on finalisation of the trial. In closing submissions the parties agreed that the costs of the application awarded to the plaintiff on 6 February 2018 should follow the costs of this action.

PRELIMINARY MATTER – WHETHER MAJOR ENGELBRECHT IS AN EXPERT WITNESS

The plaintiff’s first witness was Major Johan General Harold Godfrey Engelbrecht. He is a former police officer and investigator. The defendants objected to Major Engelbrecht being called as an expert witness. The defendants’ first objection being that Major Engelbrecht was not an expert and secondly that his evidence was merely an opinion, not expert evidence.

The defendants argued that the Court should not allow his evidence as the court must decide on the issue of negligence from the witnesses, standing orders, policemen and judgments on how dockets should be handled and investigations completed. The defendants further objected to Major Engelbrecht’s evidence being led because if it emerged that he is not an expert the court will not be able to ignore its very harsh findings.

The regulated procedure requires the parties to give notice of their intention to call the witness and in that notice to lay the basis on which the court can determine whether he is suitably qualified to express an opinion and to put out a summary of the opinion.

According to the notice Major Engelbrecht was a policeman for 43 years. He has since retired and is now a consultant. At time of retirement he was a major general. Although Mr Mouton for the defendants cautioned me that there would be “chaos” in our courts if evidence of his nature was allowed, I decided that prior to ruling on the value of his evidence as an expert I must first hear his evidence. I accordingly overruled the defendant’s objections.

The evidence of Major Engelbrecht was tendered on the basis that he was an expert in police search and rescue operations and in subsequent criminal investigations. He was to assist the court in regard to the alleged deficiencies in the manner in which the SAPS searched for the plaintiff and in the manner in which the investigation was conducted.

Major Engelbrecht’s qualifications are set out in his curriculum vitae accompanying the Rule 36 notice. He has a national diploma in police administration and a degree in police science. During this time he studied criminology, criminal law and criminal procedure but he also studied crime investigation. He testified that a study of criminal investigation involves how one should conduct an investigation from the beginning to the end when you end up testifying in court. His curriculum vitae reflected that he received many medals, awards and achievements.

Since qualifying, Major Engelbrecht has attended multiple courses including training courses and detective training courses. These all assisted him in his development as a detective. Major Engelbrecht has also developed training courses for the police, written lectures on crime scene investigation and case management. Because of his experience he could investigate massacres, mass murderers and violent crimes. He was involved in the development of a serious violent crime course, developed the curriculum for the murder and robbery unit members, and did substantial research to develop such courses.

As a policeman, Major Engelbrecht was involved in serious and violent crimes. He was an investigator and a commander, guiding those serving under him and training senior officers. Major Engelbrecht testified that as an investigator he investigated the crime of rape on many occasions as both a junior and senior investigator and as a commander in charge of a policemen investigating rape.

Major Engelbrecht testified that he has experience in searching for missing persons, conducting searches with dogs whilst he was the acting commander of the dog training SAPS Pretoria West 1994-95 and conducting searches accompanied by helicopters.

Having established his expertise based on his qualifications and experience, Major Engelbrecht proceeded to comment on the manner in which Ms K’s rape was investigated and dealt with. For the purpose of forming his opinion he was provided with the plaintiff’s bundle of documents and this included the docket.

Major Engelbrecht commenced with setting out how a ground search with a sniffer dog and an air search with a helicopter should have been conducted. He concluded that it was highly unlikely that W/O Gerber conducted the ground search with his dog Kojak or that the helicopter searched the area.

He testified that if the police dog and police vehicle had searched the area in question, it is likely that the plaintiff would have run out to the police and been found because in his opinion this commonly occurs in about 99% of the cases he is aware of.

He gave evidence on the use of a helicopter with a night sun. He had flown in a helicopter with a night sun several times. It was strong enough to view rabbits and small animals on the ground. In his opinion it is so effective in illuminating terrain that had the SAPS used it they should have found the plaintiff.

On the basis that the SAPS did not find the plaintiff either with the ground search or helicopter search he concluded that the SAPS did not in fact undertake either search and on those grounds they were grossly negligent.

Major Engelbrecht then gave his opinion on how he thought a proper investigation should take place.

He commenced with criticising the undue delay of the SAPS in responding to the call from the joggers.

He criticised Solomons for the manner in which she compiled the identikit.

He detailed deficiencies in the manner in which SAPS had conducted the investigation. Because of the findings I make, it is not necessary to detail these deficiencies at this stage.

The difficulty that I have with Major Engelbrecht’s opinion is that he expressed an opinion based on facts which were conveyed to him by the plaintiff and her legal advisers. It was to a large extent based upon facts of which there was no proof. In turn, as there was no proof of the facts on which his opinions were based, those opinions were irrelevant and inadmissible. His evidence was tendered on the basis that he was an expert witness and qualified to express an opinion.

It is necessary therefore, in considering his evidence relative to the question of the search and subsequent investigation to consider when a witness may give evidence as an expert and what constraints operate in relation to such evidence. Major Engelbrecht’s evidence can then be measured against those standards.

Nugent JA dealt extensively with opinion evidence in the Price Waterhouse Coopers case.7 In this matter he said that opinion evidence is admissible ‘when the Court can receive “appreciable help” from that witness on the particular issue’.8 That will be when:

‘… by reason of their special knowledge and skill, they are better qualified to draw inferences than the trier of fact. There are some subjects upon which the court is usually quite incapable of forming an opinion unassisted, and others upon which it could come to some sort of independent conclusion, but the help of an expert would be useful.’9

As to the nature of an expert’s opinion, in the same case, Wessels JA said:10

‘… an expert's opinion represents his reasoned conclusion based on certain facts or data, which are either common cause, or established by his own evidence or that of some other competent witness. Except possibly where it is not controverted, an expert's bald statement of his opinion is not of any real assistance. Proper evaluation of the opinion can only be undertaken if the process of reasoning which led to the conclusion, including the premises from which the reasoning proceeds, are disclosed by the expert.’

These principles confirm the point made by Diemont JA in Stock11 that:

‘An expert … must be made to understand that he is there to assist the Court. If he is to be helpful he must be neutral. The evidence of such a witness is of little value where he, or she, is partisan and consistently asserts the cause of the party who calls him. I may add that when it comes to assessing the credibility of such a witness, this Court can test his reasoning and is accordingly to that extent in as good a position as the trial Court was.’

Nugent JA in the same judgment considered the following passage from the judgment of Justice Marie St-Pierre in Widdrington12

‘Legal principles and tools to assess credibility and reliability

“Before any weight can be given to an expert’s opinion, the facts upon which the opinion is based must be found to exist”

“As long as there is some admissible evidence on which the expert’s testimony is based it cannot be ignored; but it follows that the more an expert relies on facts not in evidence, the weight given to his opinion will diminish”.

An opinion based on facts not in evidence has no value for the Court.

With respect to its probative value, the testimony of an expert is considered in the same manner as the testimony of an ordinary witness. The Court is not bound by the expert witness’s opinion.

Major Engelbrecht’s opinion in relation to the ground and air search has no value for the Court because he bases his opinion on facts that are not in evidence, which is that the ground and air search did not take place at all. Similarly his evidence in regard to delay in attending to the plaintiff when the SAPS were called by the joggers and the manner in which the identikit was compiled ,has no value at all because his opinion is based on facts not in evidence.

CONSTITUTIONAL OBLIGATIONS OF THE STATE AND THE POLICE AND THEIR RELATIONSHIP WITH CITIZENS

The State has constitutional obligations to respect, protect and promote the citizen’s right to dignity, and to freedom and security of the person.13

Equally relevant is the state’s establishment of a police service for the efficient execution of its constitutional obligations to prevent, combat and investigate crime, to protect and secure the inhabitants of the Republic and their property, and to uphold and enforce the law14.

The trust that the public is entitled to repose in the police also has a critical role to play in the determination of the Minister’s liability in this matter15.

The SAPS admits that it had a duty to search for the plaintiff and to investigate the complaint that she had been raped.

It is also common cause that the SAPS had a duty to:

carry out a search for the plaintiff with the care, diligence and skill required of reasonable police officers;

investigate the allegation of rape by her with the care, diligence and skill required of reasonable police officers.

What this court must decide after having heard all of the evidence is whether SAPS complied with this obligation in respect of the plaintiff.

NEGLIGENCE

It is most convenient to begin with a discussion of negligence. The well-known test for negligence is set out by Holmes JA in Kruger v Coetzee16. This test prescribes that negligence would be established if.

‘(a) a diligens paterfamilias in the position of the defendant –

(i) would foresee the reasonable possibility of his conduct injuring another in his person or property and causing him patrimonial loss; and

(ii) would take reasonable steps to guard against such occurrence; and

(b) the defendant failed to take such steps.

This test has been applied by this Court for some 50 years. Requirement (a) (ii), whether a diligens paterfamilias in the position of the person concerned would take any guarding steps at all and, if so, what steps would be reasonable, must always depend upon the particular circumstances of each case.

The plaintiff testified in detail about the night of 9 and 10 December 2010, the impact of that traumatic incident on her life, her perception of the police search and subsequent police investigation and its perceived shortcomings and how her life has changed to the extent that it has. I will discuss her evidence in the paragraphs below dealing with the search and the subsequent investigation.

The Search

Initial foot search

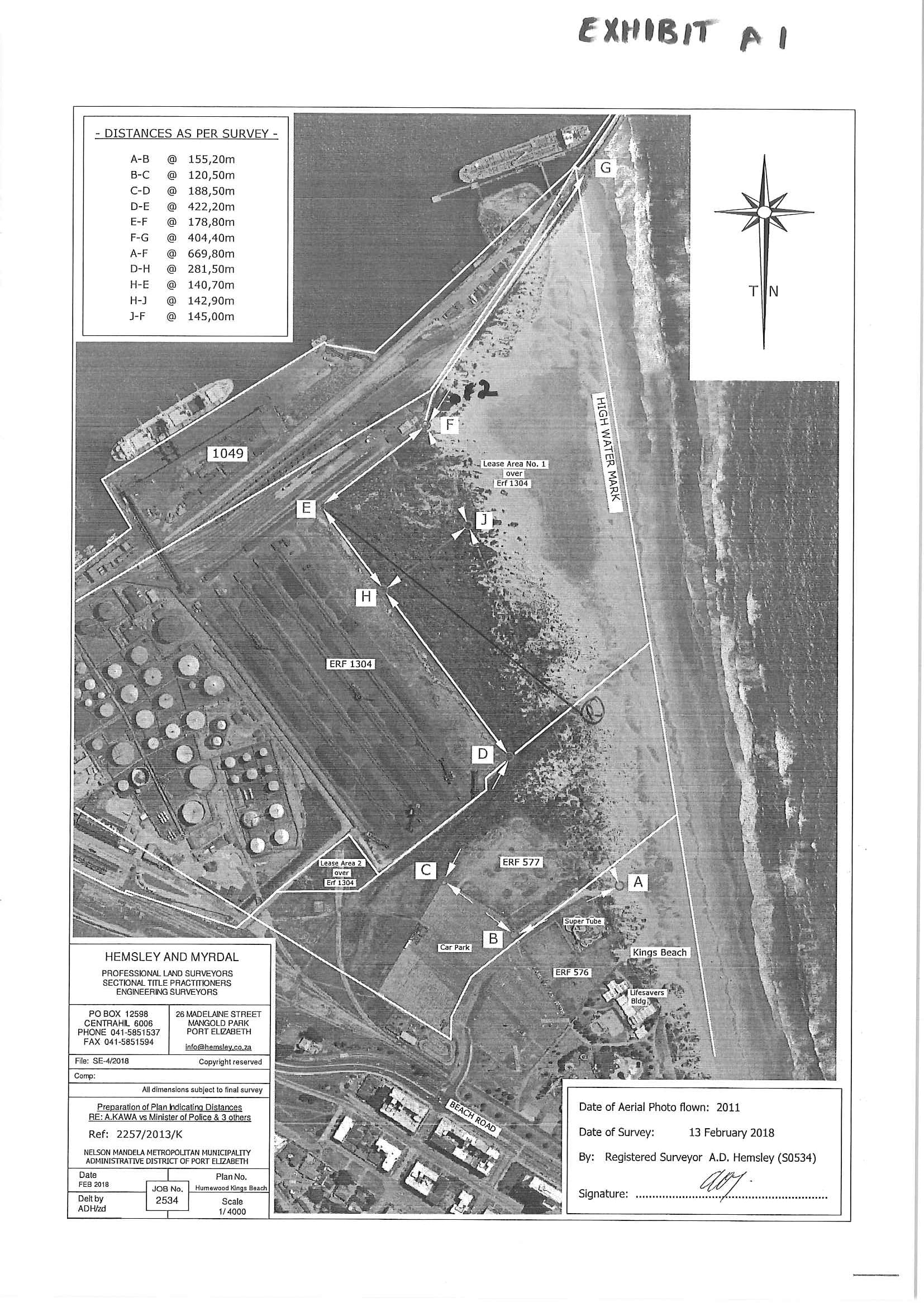

At the commencement of the trial the court and the parties attended an inspection in loco. A minute of this meeting was filed and Exhibit A1 was prepared which is an aerial view of Kings Beach parking lot, the beach and the dunes up to the harbour wall. Various points were marked on this exhibit and both parties referred to it extensively at trial. I have for ease of reference included this map below.

Although initially disputed between the parties, agreement was reached as to the exact location that the plaintiff was held overnight, duly marked on Exhibit A1 as point “F2”.

The police discovered the plaintiff’s car in the car park at Kings Beach at approximately 23h30 on the night of 9 December 2010. Radio Control was alerted, as well as the plaintiff’s family, some members of whom shortly thereafter attended at the scene.

Mr Majwa, was alerted to the finding of the plaintiff’s car. He testified that he arrived at Kings Beach parking lot before 24h00. There were six SAPS members in attendance when he arrived. Shortly afterwards, another four arrived.

A first responder, W/O Rae of the K9 Unit, attended on the scene. W/O Rae deemed it necessary to alert the K9 Search and Rescue Unit. W/O Gerber of this unit, received this call at 00h25 and attended at the scene at approximately 00h45. On arrival at the scene, W/O Rae and also Sergeant Pretorius briefed W/O Gerber on the situation. W/O Gerber did not recall any other policemen being present at that time.

W/O Gerber testified that from W/O Rae’s briefing, it appeared that the SAPS members who were at the scene before he arrived had not searched the beach area on foot. They had instead called for called for W/O Gerber’s assistance. This accords with Mr Majwa’s evidence that when he arrived at the beach the SAPS members were in the car park and were not out searching for the plaintiff.

None of the SAPS officers who were present at the scene before W/O Gerber arrived were called to give evidence. Thus, W/O Gerber’s is the only evidence about what the ground crew did before he arrived. There is no evidence before this court to show that any of the SAPS members who first arrived on the scene conducted even a cursory search for the plaintiff.

The Dog Search

W/O Gerber was tasked with searching the area with his search and rescue dog, Kojak.

Mr Olivier, called by the plaintiff as an expert, is a former officer and captain in the South African Police Service. During his tenure he was instrumental in the development of the SAPS dog unit and the research and training of the SAPS dogs and their handlers. He testified that search and rescue dogs are trained to conduct two types of searches, ground searches and air-borne searches.

The latter type of search is conducted when there is no visible ground track. The dog follows an air-borne scent, namely scent molecules from the victim, which are distributed by the wind. The scent is distributed in a cone or “V” shape, with the source (the victim) at the tip of such. The wind then distributes the scent in a cone or “V” shape away from the victim. Thus, it is extremely important for the dog handler to conduct the search into the wind, in other words towards the direction from which the wind is blowing.

When the dog handler reached the scene, he would normally be briefed by the “first responders” who would inform him what they had already found, in other words, where they had already searched. The dog handler would then plan his search before he conducted it. The dog handler decided where the dog searched. W/O Gerber confirmed that this was the approach he took.

A weather report of the night in question indicated that the wind was gentle and was blowing from the sea towards the iron ore camp. In those conditions, it would have been most effective to have conducted a “Z” or “zig-zag” search. This is a search pattern in which the dog handler walks in a pattern that resembles a capital letter “Z”.

It was necessary for the SAPS dog handler to search the area marked “F” to “G” on Exhibit “A1”, because it was necessary to search the whole area. Mr Olivier testified further in this regard that even if he had not known that the area continued beyond “F”, in other words, if the area “F” to “G” did not form part of this original plan, he would have added to his search when he reached “F”. This was because it was necessary to search the whole area.

With reference to Exhibit “A1”, he testified further that if the SAPS dog handler walked from “F” to “G”, he would definitely have found the plaintiff if she was being held in the area that is marked “F2”.

Mr Olivier’s expert opinion on the prospects of success of a dog search, if conducted properly was as follows:

“The experience that I have gained yesterday, the shrubs are not that thick either; I am not sure what the shrubs then was but although, even if it was more dense than yesterday, it not a very difficult search area and a trained dog which is up to standard…the dog will not miss”

W/O Gerber who conducted the search that night for SAPS was an experienced policeman and dog handler. He had been in the SA Police Service for 25, which 23 of those years would be at the K9 Unit. He testified as follows:

He confirmed Mr Olivier’s evidence that before a dog handler begins to search, he needs to plan his search and decide on the area to be searched.

Before he began his search, he drove his vehicle up the beach, along the shoreline, until he was approximately 50 metres away from the harbour wall. He stopped just short of the harbour wall because the lights from his vehicle illuminated the area right up to the wall and he could see that there was no one there. He then turned back.

He then conducted an initial search of the patch of dunes to the south of the car park, this is where he found three bush-dwellers. He had no more than a cursory conversation with the bush-dwellers. He did not record their names or take a statement from them or request one of his colleagues to do this.

Following this he moved his search to the western side of the car park towards the harbour wall. He conducted his search in a “saw tooth" fashion which is the same as the “zig zag” pattern that Mr Olivier recommended. W/O Gerber confirmed that he searched the dune area between “D” and “E” and “F” and back along the red line to point “R”. The search commenced at point “D”.

The dog was off leash; they are trained to search off leash, which means the dog would be roughly 20 to 25 metres ahead of W/O Gerber.

W/O Gerber testified that he moved from point “D” towards point “E” but that he did not walk right up to point “E” because as soon as the dog reached the boundary of the area that he had decided to search, W/O Gerber called the dog, turned around and walked the next leg. As soon as W/O Gerber saw the dog make contact with the fence he called the dog and turned around. At this point only the dog and not his handler will have made contact with the fence.

He would then have done the second leg of the search in a south easterly direction from “E” to “R” and then the third leg of the search was back up towards point “F”.

According to W/O Gerber the dog reached the fence which was a high palisade fence near point “F” but he confirmed that he himself did not walk right up to the fence. He was not aware that there was a kink in the fence at this point and that the bushes extended beyond point “F”. As far as he was concerned when the dog reached point “F” he had completed that leg of the search and he turned around and walked with his dog back to his vehicle.

It is common cause that the plaintiff was not found during the search by W/O Gerber. It only became common cause late in the trial that the plaintiff was actually held captive at point “F2” on Exhibit “A1”, being a point along the northern palisade fence in the dense bushes north-east of point “F” on Exhibit “A1”.

W/O Gerber made a contemporaneous note of his search recording the following:

“I decided to search the nearby sand dunes and shoreline with the dog. The search was done and only three bush dwellers were found by the dog. It was decided to call air support for assistance.”

The plaintiff argues that because W/O Gerber and his dog did not find the plaintiff and because of his contemporaneous note, he did not in fact search the area to the north of the car park and he only searched the nearby sand dunes to the left of the car park and that he then called out the helicopter to search the dunes to the left of the walkway. The plaintiff suggests that the reason why W/O Gerber did not search the area to the left of the dunes is that he was concerned for his own safety. The plaintiff says her view is fortified by the fact that in his evidence he confirmed that he had searched the sand dunes and the shoreline and that as he had not found the plaintiff she could not have been there. He was adamant that had she been in the area he had searched he would have found her.

W/O Gerber’s explanation as to why he did not find the plaintiff is that the wind was blowing directly east on the night in question and his dog Kojak, only searched up to the fence in the vicinity of point “F”. When his dog reached this point, W/O Gerber called him back and continued the search back in the direction of the car park. It was established that the plaintiff had been held at point “F2”, the wind would have blown the “scent cone” past the dog’s nose.

I accept W/O Gerber’s explanation as to why he did not find the plaintiff. I do not accept the suggestion by the plaintiff that he did not find her because he did not search the area “D”,”E” “F” to “R” and only searched the area to the right of the car park. I found W/O Gerber to be an honest witness. He clearly articulated the manner and method used to search for the plaintiff. There is no reason to believe that his entire evidence was fabricated and that he did not conduct the search which he says he conducted. The plaintiff’s suggestion that he did not conduct the search is based only on the fact that he did not find her. But his explanation as to why he did not find her is plausible and demonstrates the short comings in the manner in which he undertook his search and he made significant admissions against his own interest.

The Helicopter Search

W/O Smith (“Smith”) testified that the helicopter received the call from 10111 at 01:30 to report to Kings Beach. It took off at 01:45. This is confirmed by the record.

The search was conducted with a Messerschmitt B0-105. The helicopter was fitted with a light known as the “night sun” and it was not fitted with a “fleur”, which is a camera with infrared imaging that would have been able to detect the heat from a person located near it.

W/O Smith is a member of SAPS and was on duty on the night of 9/10 December 2010. He was the air law enforcement officer (ALEO) in the helicopter that night. In his words, he was an extra set of eyes and ears for the pilot. He operated the west night sun and would have operated the fleur camera if they had one.

It appears that the helicopter requested at 01h30 took off at 01h45. On arrival at Kings’ Beach the pilot and W/O Smith were briefed by W/O Gerber and requested to search the area “D”,”E”,”F” to “R” on the corner.

The flight team decided to commence their search with a search of the shoreline. From the point “B”, along the shore up to the harbour wall. The reason for this decision was to exclude a possible “drowning”.

Smith testified that the helicopter flew about 30-50 metres above the ground. He had a clear view of the ground. The search lasted approximately 20 minutes. The “night sun” has the illumination of approximately 20 million candles, it can be set so that the light is cast wide or it can set to a pin point. On the night in question the light was set to about half way between a pin point and a full circle as the helicopter was flying low. The illuminated search area would be about 15 to 20 metres and the air crew had a clear view of the ground.

The helicopter then searched the areas marked ‘“D”,”E”,”F” to “R”. W/O Smith explained that the area from “E”, “F” to “G” was a non-fly zone, i.e. beyond the perimeter fence. They were not allowed to cross it. They went close to the line but not across it. However, they went close enough to see the road on the other side of the fence and the area before the fence.

In cross examination Smith indicated that the helicopter would not have come within 15 metres of “F2” because of the no-fly zone.

W/O Smith also conceded that he was briefed by W/O Gerber to search the area but not specifically instructed to search “F” to “G”. This despite the fact that W/O Gerber had just completed his search and failed to search this area. He also testified that even had they flown over the plaintiff it was unlikely that he would have seen her if she had been hidden under the bushes.

W/O Smith confirmed that he was aware that there were bushes and dunes along the harbour wall area, but he did not recall whether they angled the lighting so that, although they were not able to fly right up to the harbour wall due to the ‘no go’ zone, they would be able to see along the line of dunes and bushes along the harbour wall. He confirmed that if they had shone the light towards a particular area, clearings in the bush would be illuminated by the “night sun”. In the circumstances had they hovered above the area marked “F2” and had there been blankets or towels in the clearing they would have been seen from the helicopter.

W/O Smith conceded further that although he was in radio control with the SAPS members on the ground he did not inform them that the helicopter was unable to fly close to “F” or “G”. Nor did he report this after the search was completed.

After about 20 minutes, the search was terminated. Smith’s reasons for terminating the search were that the mist was thickening and there was an incoming aircraft. They were not allowed to have two aircraft in the air at the same time and were requested to land. The air search ended without the plaintiff being found.

The flight’s GPS’s records were not available to the parties for trial as they are not stored and are deleted from time to time.

The plaintiff testified that she was under a sleeping bag or blanket in a clearing in the bushes. When she heard the helicopter, she in fact asked to be allowed to urinate and did so close to the sleeping bag so that she would have an excuse to move the sleeping bag closer to the clearing, which she did. Thus, if Smith had searched the bushes at “F2”, he would have seen her.

She also testified that she heard the helicopter in the distance but not above her. She was also at no stage aware of the “night sun”, which she would have seen, even through her blind fold. She also specifically asked her perpetrator whether he could hear the helicopter to try and gauge his reaction to it, but he was completely unperturbed by it. I do not accept that the only reasonable inference is that the helicopter did not fly near where the plaintiff was being held captive. There were many inconsistencies in the plaintiff’s evidence and many details of the night in question which she did not accurately recall. I accept the evidence of the police about the path of the search that they took. They made significant concessions about the shortcomings of their search, against their own interest.

The plaintiff gave evidence as to how distressed she was when she realised that the helicopter search was not going to find her and she heard it fading into the distance. She realised then that she was probably going to be held captive much longer and that help was not at hand.

Conclusions in Respect of the Search

The plaintiff alleged in her original particulars of claim that the SAPS “refused” to enter the area where she was held captive. In her amended particulars of claim she alleges that they “failed and/or refused” to do so. The plaintiff submitted that the only reasonable conclusion which this Court can draw is that SAPS was negligent in the manner in which it conducted its search.

The evidence demonstrates that while a search was in fact conducted, the actions of the SAPS officers at all times fell below the standards reasonably expected of them.

None of the SAPS officers who were present at the scene before W/O Gerber arrived, were called to give evidence. W/O Gerber’s is the only evidence about what the ground crew did before he arrived. Thus, the only reasonable conclusion that the Court can draw is that the SAPS officers who were at the scene before Gerber arrived did not conduct a search whilst waiting for him to arrive.

SAPS members could have, but did not, conduct the most basic of foot searches. Thus they did not walk up the beach with their torches and search the sparse dunes to the right of the walkway or the dunes from “F” to “G”. This is the least that would have been expected of reasonable SAPS officers in their position.

Thus, if the SAPS members had conducted such a search, they may have walked into the plaintiff and her perpetrator. Given the restricted size of the area, it would in all likelihood not have taken the SAPS members longer than an hour to conduct such a search. The Plaintiff would have been found by 01h00.

The plaintiff was also let down by both the dog unit and the helicopter search because they inexplicably both failed to search beyond point F and did not search the area between point “F” up to point “G”.

W/O Gerber was aware of the northern boundary of Kings Beach, namely the palisade fence and the harbour wall, and of the fact that there were sand dunes along this boundary. W/O Gerber conceded this:

“You were aware of the harbour wall, you have said that before. So you must have been aware that the harbour wall extended all the way from the sea inland, not so? Correct, yes.

And you say that you didn’t yourself check what was in front of the harbour wall?

...I know what was in front of the harbour wall

What was in front of the harbour wall?

It is all these big rocks and dolosse that comes from the wall up to inland and then you have got the sand dunes running at the top, yes.”

…

“And so what you became aware of as you have already told us was the harbour wall area and the area in front of it all the way up, you must have been aware of this dune area with the vegetation which would have been to your left as you face the harbour wall, not so?

I was aware there were dunes, yes.”

Yet despite this, W/O Gerber elected to end his search when his dog reached point “F”. He conceded in this regard that he made the decision not to walk from “F” to “G”. It was a significant and glaring omission in his investigation that he did not search the area where she was held captive “F2” on Exhibit “A1”, being a point along the northern palisade fence in the dense bushes north-east of point “F” on Exhibit “A1”.

He was negligent in that he stopped his search 20m short of point “F”. He should have walked up to point “F” to make certain that there was no point beyond this to search. Had he done so, given that his trained sniffer dog was ‘off lead’ and, as per the evidence from him, would have been 20m ahead of him, it would probably have found the plaintiff. This would have been at approximately 1am on 10 December 2010 thus reducing the further trauma experienced by the plaintiff of hearing the helicopter fly over, and fly away, and further violations in the form of rape over the next number of hours.

Had W/O Gerber conducted himself in this manner, which one is entitled to expect of a reasonably competent police officer duly exercising his skills, he would also have realised that the area did not end at point “F” and that there was a greater area to cover right up to the harbour wall. It was not reasonable of him to end his search where he ended it. The evidence in fact showed that he was aware that the area extended further, as he had earlier driven up the harbour wall and noticed that there were “dollos”, bush and dunes against the harbour wall. Despite this, he did not search this area.

Similarly, I am of the view that the helicopter search fell short of what was required from a helicopter search and rescue operation. The plaintiff would not concede that the helicopter flew over the whole dune area, but it is clear from all the evidence that it did search the area with a very strong “Night Sun” search light. Unfortunately the evidence is equally clear that the helicopter did not conduct an effective search beyond point “F” on Exhibit “A1” and I can only conclude that they did not find the plaintiff because they did not fly over where she was held at point “F1” on the map, or they did not hover close to that area and direct the “night sun” towards the bushes in the ‘no-fly’ zone.

W/O Smith said that the search was terminated because there was a second aeroplane coming in to land. It was clearly terminated early and a critical part of the area remained unsearched by both W/O Gerber with his dog and W/O Smith with the helicopter.

Smith’s evidence serves to confirm that there was no proper command and control of the search and no communication and co-ordination between the various SAPS units. It is my finding that this in itself constituted negligence on the part of SAPS.

It also serves to highlight the extreme indifference on the part of SAPS in relation to ensuring that the area was properly and effectively searched. From the ground crew to W/O Gerber to the SAPS helicopter crew – all simply went through the motions of searching without conducting a reasonably effective search, or indeed anything vaguely resembling such, at all.

The Investigation

The plaintiff’s particulars of claims set out a number of grounds upon which she claims the defendants acted in breach of their duty of care in the investigation after she escaped.

I will deal with each ground as set out in the particulars of claim.

Delay in responding to the initial call from Mr Britz

The plaintiff alleged that the police delayed in responding to a call by one of the joggers who had assisted the plaintiff after she had been found on the beach after the rape ordeal. It is evident from the docket and evidence presented to this court that W/O Andrews had received a call at approximately 07h15 to attend to the matter at Kings Beach and that he arrived there at approximately 07h25 – 07h30. The plaintiff did not persist in her claim that there was an inordinate delay in responding to Mr Britz and the call from the joggers. I accept the evidence that the SAPS responded as soon as it was reasonably possible for them to do so.

Delay in searching for and taking statements from possible suspects and/or witnesses and failure to take reasonable steps to identify suspects and/or witnesses

The plaintiff alleged that the SAPS failed or delayed in interviewing or taking statements from Mr Britz. Both W/O Andrews and W/O Madubedube omitted to obtain a statement from Mr Britz. They should have done so as this is what a reasonable investigating officer would have done. I agree though that their failure to do this was in itself not a material factor contributing to any negligence on the part of the investigation.

However, I agree with the plaintiff’s allegation that the SAPS failed or delayed in searching the area for “bush dwellers” living in the sand dunes in the vicinity of Kings Beach and failed to round up and/or photograph those bush dwellers to enable the plaintiff to attempt to identify her abductor or to take statements from them or to interview them on the morning of 10 December 2010 or thereafter.

W/O Gerber found three bush dwellers when he commenced his foot search in the early hours of the morning of 10 October 2010. They were not taken in for questioning and neither were their names recorded by him or any other SAPS member present at the time. While it cannot be expected that W/O Gerber would delay his foot search by questioning the bush dwellers and taking their statements, it is reasonable to expect the other SAPS members in attendance at the time would do this. These bush dwellers could have had critical evidence which would have been valuable in terms of both finding the plaintiff and identifying her assailant.

There is no evidence to suggest that W/O Andrews who was on duty on 10 December 2010 sought any assistance in following up on the plaintiff’s description of her assailant(s), or that he or any other SAPS members searched the beach area for possible suspects. There is no record of W/O Andrews having made any effort to obtain or to view the CCTV footage from 10 – 12 December 2010 to try and identify suspects or witnesses. W/O Andrews was not called to testify and no explanation has been provided for these omissions. W/O Andrews as a reasonable investigator should at the very least have done this.

W/O Andrews did arrest one dweller, Jakavula, for being in possession the plaintiff’s clothing. The bush dweller Mancane was also arrested. It is evident from his statement and that of W/O Andrews, that he was arrested because he was connected to Jakavula and to the plaintiff’s clothing. It is also evident that, on his version, he was asleep in the Kings Beach bushes on the night of 9 – 10 December 2010.

Thus, he ought to have been considered a suspect in respect of the abduction and rape of the plaintiff until eliminated.

Other than arresting Jakavula, W/O Andrews, did not do anything else to try and identify other suspects. In particular, he did not carry out an investigation of bush dwellers from Kings Beach and neighbouring beaches.

The case was handed over to W/O Madubedube on 13 December 2010. W/O Madubedube conceded that when investigating violent crimes against women it was important to act quickly. The faster you acted, the more likely you were to apprehend suspects. He knew this both from courses which he had attended and from his practical experience with investigating violent crimes against women. Common sense also dictates that this is a critical period for the investigation.

It is clear from the evidence that the first time the bush dwellers were rounded up was on 15 December 2018, five days later, when this was done by the municipality in preparation for the Christmas season. The rounding up of the dwellers was organised by the municipality and not SAPS.

W/O Madubedube was informed of this and made an arrangement for the plaintiff to attend an informal identification parade.

W/O Madubedube knew that Mancane had been arrested and released. He also knew that he had been arrested because he was connected to Jakavula and the plaintiff’s stolen clothing. He also knew that DNA analysis would be crucial in the plaintiff’s case and that Mancane had been released without his blood being drawn for the purposes of DNA testing. Yet, from 13 – 14 December 2010, he did nothing to try and find Mancane in order to interview him and to draw blood from him for DNA analysis.

W/O Madubedube’s explained that he did not do this because W/O Andrews had already excluded Mancane as a suspect and that his hands were consequently tied. It was apparent that W/O Andrews had excluded him as a suspect in relation to the theft out of the plaintiff’s vehicle and had not considered him as a suspect in regard to the rape. W/O Madubedube knew that Mancane was a bush dweller who was there on the night that the rape took place, and yet chose not to track him down take a statement from him to test his statement to W/O Andrews that he knew nothing about the rape.

W/O Madubedube was now the investigating officer and was under a duty to carry out a reasonably effective investigation regardless of who W/O Andrews had or had not excluded as a suspect. His second explanation is that the plaintiff did not point him out as a suspect. Clearly the onus was not on the plaintiff to point out Mancane before W/O Madubedube could interview him.

W/O Madubedube’s failure to take statements from witnesses and to follow up on relevant information provided to him by witnesses

The plaintiff alleges that there were a number of ways in which W/O Madubedube was negligent by failing to take statements and following up on information provided to him by witnesses. For example, one of the grounds of complaint against W/O Madubedube is that he failed to take statements from the car guards called Francis and Eldridge whose details the plaintiff had given him and who she believed knew who her abductors and associates were.

W/O Madubedube’s “investigation done” note in the docket shows that as early as 15 December 2010 he had already:

(i) appointed Eldridge Ruiters as an informer;

(ii) circulated the identikit prepared by Sergeant Solomons;

(iii) Eldridge (so he testified) had told him that the identikit compilation appeared to represent an image of “Xolani” (later changed to “Bongile”);

(iv) identified possible suspects who were “gossiping” (apparently when they were under the influence of liquor), amongst whom were one “Prince”, sometimes called “Chris”, as well as Xolani;

“Mancane” (Themba Mauopa) was also a suspect;

Jakavula had been arrested and was also a suspect;

He had spoken and obtained the contact details of all the relevant officials from Security Services and the Beach Co-ordinating Office of the Municipality;

He had made contact with the Humewood CID to help him in his search for the perpetrators;

He had the details of Mr Rampo at the Humewood Fire Station and indicated that he had already interviewed Mr Rampo at that stage;

He had the contact details of Mr Majwa.

SSG private investigators were appointed on behalf of the plaintiff in February 2011 to assist in the police investigation. SSG specifically recorded that “several informants” had been tasked by the SAPS to assist in tracing the perpetrators.

In both the aforesaid investigation note and in the investigation diary W/O Madubedube recorded that he had tasked official informers at Kings Beach, as well as unofficial ones, such as Eldridge Ruiters, to assist with his investigation. This included a certain Mr Mpumlo who worked at the Municipal Beach Office and who claimed that he knew all the bush dwellers around Kings Beach.

In evidence and having reference to his pocket book, W/O Madubedube also confirmed the chronology of the tasks that he performed on 15 December 2010 as follows:

He attended a formal identity parade at St Albans prison at which the plaintiff was asked whether she could identify her assailant;

Thereafter at approximately 10.20 he has a meeting with a meeting with informers. The informers who he spoke to were Mr Eldridge Ruiters, Mr Robile, Mr Mpumza and Mr Rampo;

W/O Madubedube knew that Mr Ruiters worked in the Kings Beach area, that he was in the King’s Beach area on 9 - 10 December 2010 and that he knew the bush dwellers who lived at Kings Beach;

Mr Ruiters gave him information about five suspects, who he informed W/O Madubedube were “gossiping under the influence”, in other words, talking about having been involved in the plaintiff’s rape when drunk. The five suspects were “Bongile”, “Chris/Prince”, “Xolani”, Mancane and Jakavula;

W/O Madubedube showed Mr Ruiters an ID kit photo previoulsy prepared with the plaintiff by Sergeant Solomons on 12 December 2010. Mr Ruiters identified the person in the ID kit photo as “Bongile”. It is common cause between the parties that the reference to “Bongile” was in fact a reference to Sibongile Lawrence.

W/O Madubedube also testified that, apart from drunken gossip related to him by various informants, he never obtained any “tangible evidence” from Ruiters or any other informant for that matter, which assisted him in tracing the perpetrators. It is submitted by the defendants that Madubedube’s professional opinion as an experienced detective, that he received no information from Ruiters or anyone else on which he could reasonably and lawfully arrest anyone, was vindicated by subsequent events.

The allegation by the plaintiff that Ruiters clearly knew her assailant was not supported in evidence, since several of the persons he named were eventually cleared by DNA evidence. However, the fact that several of the persons named by Mr Ruiters were found with the plaintiff’s clothing and belongings, did suggest that he had pertinent information about the attack on the plaintiff that was important to investigate.

W/O Madubedube conceded that he in effect took no steps to track down the persons whom Mr Ruiters identified as possible suspects on 15 December 2010. He made no attempt to track down the suspects “Chris/Prince” or “Xolani” other than to speak to informers at the beach which from his pocketbook he did on two occasions only, namely 15 December 2010 (when Mr Ruiters first provided with the information regarding the possible suspects) and on 7 February 2011.

He made no attempt to track down “Bongile”, whom Mr Ruiters had in fact identified as the person in the ID kit photo, other than speaking to his informants.

He ultimately had no explanation for his failure to follow up on the information that Mr Ruiters provided to him, save that in relation to Mancane, the information was “hearsay” and that he could therefore not act upon it.

Furthermore, W/O Madubelube failed to effectively follow up on the information received from Ruiters in the informal identity parade.

The municipal security officers informed W/O Madubedube that they were rounding up the beach dwellers from the area. They suggested that he contact the plaintiff and request her to come to Kings Beach for an informal identity parade. He did so.

He testified that he arranged for the bush dwellers to be lined up and asked the plaintiff to try and identify her assailant. He knew that after the line up the municipality intended to remove them from the bush area and therefore he should have known that he may never see the bush dwellers or have the opportunity to interact with them again. He did not take the names and details of the bush dwellers. He did not ask any of them whether they knew Sibongile, Xolani, Prince/Chris or Mancane. He did not ask Mr Ruiters whether any of these suspects, whose names he had just provided him with, were amongst the bush dwellers present at the informal identity parade. He also did not ask Mr Mpumlo.

He pasted the ID kit photo at the municipal offices at Kings Beach, but he did not ask the municipal officers, including Mr Mpumlo, whether they knew or recognised the person depicted in it. It was not clear from his evidence whether or not he asked the bush dwellers whether they recognised the person in the identity kit photo. His response was evasive and he simply said that he had distributed it amongst the bush dwellers. This is not supported by any entry in his investigation diary or pocket book.

In any event, even if W/O Madubedube did do so, it does not assist him. This is because, on his own version, he distributed the ID kit photo to the bush dwellers but did not follow up with the bush dwellers in any way. Having distributed the ID photo amongst the bush dwellers, he did not ask them whether they recognised the person depicted in it. He failed to do so, despite knowing that they were about to be forcibly removed from the beach front and that he may never see them or have the opportunity to interact with them again.

A voice identification parade could also have been conducted as the plaintiff had been blindfolded for most of the night. This was not done.

W/O Madubedube’s failure to obtain and view CCTV footage

The plaintiff also alleged that W/O Madubedube “failed to obtain CCTV footage from the municipal street cameras and instead indicated to the plaintiff that she would have to obtain it herself” and that he “never viewed the footage and also failed to act on the footage given to him by the plaintiff”.

On 13 December 2010, W/O Madubedube contacted the plaintiff and asked her to meet him at the Humewood Fire Station in order to view the CCTV footage. The Plaintiff was accompanied by Mr Majwa. They both testified that W/O Madubedube met them at the Fire Station, introduced them to the person who operated the monitors and left shortly afterwards without viewing any footage with them. W/O Madubedube admitted leaving the plaintiff and Mr Majwa at the fire station but said that he only did this towards the end of the viewing period. It is not necessary for me to make a finding as to when W/O Madubedube left the fire station.

The first time that W/O Madubedube, or any other SAPS officer for that matter, had viewed all of the relevant footage was shortly before his testimony at trial. Until W/O Madubedube testified, SAPS’ version was that the CCTV footage had been viewed and that nothing of value could be seen on it.

Yet, during cross examination W/O Madubedube admitted that until the day before he testified, he was wholly unaware of the fact that the CCTV video footage of 10 December 2010 depicts a man, walking in the vicinity of Kings Beach and later on, loitering around the Kings Beach parking lot. Even if it is doubtful whether or not this man is a good match for the description of the plaintiff’s assailant, W/O Madubedube had not known of his existence and had done nothing to follow up on him being a potential assailant or witness.

The defendants’ submission that most of the footage would have been of no use in the sense that it would not have led to any tangible evidence which could lead to the identification of the plaintiff’s assailant is of no consequence. W/O Madubedube did not view the full CCTV footage which was available to him, as he should have.

I make no finding on whether or not W/O Madubedube obtained the CCTV footage from Rampo or via SSG. What is relevant is that he did not view all of this footage. While it is difficult to understand why the plaintiff who had appointed (and paid for) SSG to assist the police with their investigation, chose not to view the footage in an effort to try and make an identification of her assailant, it is not necessary for this court to have any regard to this in order to make a finding on whether Madubedube should have viewed the CCTV footage.

The defendants cannot rely on the assertion that it would have been a reasonable assumption on the part of W/O Madubedube that the plaintiff would look at that footage provided to her by SSGs to identify the assailant. This is a task he should have facilitated and followed up with the plaintiff on. He did not do so.

The only reasonable inference that the Court can draw is that W/O Madubedube’s inaction in relation to the CCTV footage was grossly negligent:

From the evidence at trial it can be concluded that, at most, he spent under four hours viewing the sixty hours of CCTV footage. The bulk of this time (three out of the four hours) was spent on 10 February 2011, which was an unreasonably long time after the incident occurred. W/O Madubedube missed critically important footage, namely the footage of a potential suspect. If W/O Madubedube had viewed the footage earlier on in the investigation he could have used it to try and trace the suspect, for example by showing still images of the footage to Mr Ruiters and to the bush dwellers who were rounded up by the Municipality on 15 December 2010. In addition, he could have shown it to the plaintiff in order to see whether she recognised the man who is visible on the footage of 10 December 2010.

I accept that the plaintiff’s assailant may never be found. It is not clear that she can positively identify her assailant. Whilst this may be true, it does not exonerate W/O Madubedube or W/O Andrews from their failure to view the full CCTV footage. It is clear that W/O Madubedube did not view the full CCTV footage immediately after the incident and follow up on all possible leads. The plaintiff does not need to prove that had W/O Madubedube viewed the CCTV footage it would necessarily have lead to an arrest and conviction of her assailant. She has shown that that W/O Madubedube did in fact fail to take all reasonable steps to follow up on possible leads to identify her assailant.

Failures to test DNA evidence found at the crime scene

Constable de Wal recorded that when he conducted the investigation of the crime scene, the body fluid dog was available but was not used. During his forensic investigation of the crime scene on the morning of 10 December 2010, Constable de Wal collected a number of exhibits. One those was Exhibit “A”, a piece of newspaper, which he noted had “possible blood stains on it for DNA analysis”.

On 14 December 2010, Constable de Wal addressed a letter to the Forensic Science Laboratory (“FSC”) in Port Elizabeth in relation to his forensic investigation of the scene where the plaintiff was held captive and repeatedly raped. In relation to Exhibit “A”, he noted that it had possible blood and semen stains on it and that “it looks as if someone wiped themselves on [it]”. He instructed the FSC to determine whether there was any blood or semen on Exhibit “A”, in addition to determining whether DNA analysis would be possible and to keep the exhibits safe.

On 10 February 2011, the FSC addressed a letter to W/O Madubedube. It confirmed that blood had been found on Exhibit “A”. It stated further that should the Public Prosecutor require DNA analysis, FSC should be notified four months in advance of the trial date.

No further testing or analysis was conducted in relation to Exhibit “A” until the plaintiff requested this during the course of this litigation. It emerged during the litigation process that the sample was sent to the Forensic Science Laboratory in Cape Town on 15 March 2011 to hold in safekeeping but the laboratory was not requested to analyse it. It was returned to the FCS unit in Port Elizabeth on 18 August 2011. The sample was found during the course of this year and was sent for analysis.

On 16 July 2018, when the proceedings resumed, the defendants’ counsel informed the plaintiff’s legal representatives and the Court that the test sample of Exhibit “A” was at the Cape Town Forensic Science Laboratory. It had been sent to the Pretoria Science Laboratory to be analysed and the report was expected within the week.

On 20 July 2018, Captain D Morgan of the SAPS Forensic Science Laboratory, Arcadia, Pretoria, subjected the blood stain, “A” to DNA analysis and provided a report in relation to such. The report excluded Jakavula, Mancane and Sibongile Lawrence as the donors. The male DNA profile found in the blood stain is identical to the male DNA profile found in the plaintiff’s vaginal swabs.

In examination in chief, W/O Madubedube testified that when exhibits are collected at a crime scene they are sent to the FSC PE for a preliminary investigation to determine whether there is blood or semen on the relevant exhibits. If the preliminary analysis is positive, the exhibits are sent to FSC CT for DNA analysis.

He conceded that:

By 14 December 2010, he was aware of Colonel De Wal’s letter requesting the FSC PE to determine if there was any material present on the exhibits, which would make DNA analysis possible. Thus, he was aware that DNA analysis would be crucial in the plaintiff’s case.

It was the investigating officer’s job to follow the DNA lead.

It was the investigating officer who needed to satisfy himself that DNA evidence could help.

Thus, it was the investigating officer’s obligation to follow up and to ensure that crucial DNA analysis, for example in relation to Exhibit “A,” was conducted timeously. The fact that SAPS were at all times capable of doing so was demonstrated by the fact that they did so within a week in the context of this litigation. It was clearly SAPS’ duty to analyse all available evidence.

W/O Madubedube and SAPS failed to take steps to have all the DNA evidence evaluated timeously. Doing this eight years after the fact and in response to a request for discovery in the context of civil litigation was plainly an unreasonable delay and a breach of SAPS’ legal duty to conduct a reasonably effective investigation.

W/O Madubedube’s alleged failure to follow up on information given to him by the plaintiff.

The plaintiff also alleged that W/O Madubedube “failed to follow up on information given to him by the plaintiff that her abductor had informed her that he had been recently released from St Albans Prison after serving a 15 year sentence for killing his girlfriend”.

W/O Madubedube denied this in his evidence. He stated that he did make enquiries in that regard from the prison authorities, but that they had stated to him that the information was too sparse to identify such a person. I accept this.

W/O Madubedube’s actions in arresting and charging persons that plaintiff was adamant were not the abductor.

The plaintiff further alleged that W/O Madubedube decided to arrest and charge Jakavula “in circumstances where the plaintiff had made it clear that [he] was not the abductor”.

W/O Madubedube’s pocket book, as well as the investigation diary, demonstrate that this perception of the plaintiff was wrong. W/O Madubedube was aware of the allegation of a gang-rape and accepted that he also had to look for the other rapists. I accept that it was entirely reasonable for him to follow up on leads which in his opinion were credible even if the plaintiff disagreed with him.

Jakavula was arrested by patrolling police officials over the weekend, before W/O Madubedube took over the investigation. He was arrested after he was found in possession of the plaintiff’s clothing and personal belongings stolen from her car. Two further charges (for theft and for being in possession of suspected stolen goods) were therefore added to the charge of rape. W/O Madubedube had ample reason to arrest and charge Jakavula despite the fact that the plaintiff was adamant that he was not her abductor.

W/O Madubedube’s alleged inability to conduct investigation due to lack of transport and airtime.

The plaintiff alleged that W/O Madubedube was unable to conduct the investigation properly because of a lack of transport and insufficient airtime on his cellphone. I do not agree with this. W/O Madubedube clearly had his own transport, as he was able to investigate at various places in and around Port Elizabeth, fetch witnesses, attend at Kings Beach on more than one occasion, etc. His investigation was only interrupted by a lack of transport was on the day he took over the investigation, namely 13 December 2010, when he used Colonel Engelbrecht’s vehicle and had to leave the plaintiff at the Humewood Fire Station in order to take it back to Colonel Engelbrecht.

The plaintiff’s allegation that due to SAPS inaction she had to conduct the investigation herself.

The plaintiff alleges that because of her perceptions of weaknesses in the investigation, she “herself has had to conduct the investigation and collect evidence”. I accept that her perceptions of the investigation were not entirely correct. There was aspects of the investigation that this court cannot find fault with. Certain of the plaintiff’s allegations and complaints have not, on closer examination, been supported. It may be that her incorrect perception commenced in early January 2011 when, as the plaintiff alleged, she called Colonel Engelbrecht of the FCS Unit to make enquiries about the progress in the investigation and was then told that the docket was with the prosecutors.

She testified that she understood from that that the investigation was done and that the matter had gone to Court, but to make sure about what this meant, she contacted the organisation “POWA” who apparently confirmed her notion that the investigation was complete and the matter was out of the hands of the police.

It was clearly demonstrated during her cross-examination on this score that she was under a complete misapprehension and that that occasion was just one of the many occasions where a docket in an ongoing investigation had to regularly go to the prosecutors in control of that specific case.

Both the investigation diary and the pocket book of W/O Madubedube demonstrated clearly that the investigation was not complete and was still ongoing. The plaintiff’s misunderstanding of this process led to her appointing SSG private investigators to investigate the matter.

The plaintiff also complained that W/O Madubedube did not keep contact with her and informed her as to the progress in the investigation. This complaint was not supported by the evidence which showed that Madubedube meticulously recorded each time he made contact with her and informed her about that very progress in the case (before SSG became involved).

W/O Madubedube’s evidence was that on some occasions she was courteous and on other occasions she would slam down the phone in his ear. Clearly this affected his willingness to make contact with her.

Although the plaintiff was mistaken about aspects of the investigation, it is not at all surprising that the plaintiff formed the perceptions that she did. My overall impression of W/O Madubedube is that he was a very poor witness. His evidence was laboured and wandered without clear direction. He appeared to conduct his investigation with little plan in mind. He meticulously recorded everything he did, but the overall impression one is left with is that there is much that he did not do which he could have done and should have done. He did conduct an investigation of sorts but the investigation was characterised by a number of glaring omissions which could only have left the plaintiff with the clear impression that he was doing very little to follow up on all possible leads which might lead to the apprehension of her assailant. In the circumstances it is not surprising that she became slightly “hysterical” and difficult to deal with or that she contacted a number of civil society organisations, various police officials higher up the chain of command, private investigators and eventually lawyers to try and galvanise W/O Madubedube into some sort of action.

CONCLUSIONS ABOUT THE DEFENDANTS’ LIABILITY IN NEGLIGENCE

The First Defendant, the Minister of Safety and Security

I do not agree with the defendants’ contention that “a vast majority of the plaintiff’s allegations of negligence was based on her subjective perceptions and, in the cold light of the Court, turned out to be false”. While some of the plaintiff’s allegations of negligence were not borne out by the facts, she was correct about many significant and glaring omissions.

For the reasons already outlined above, I conclude that the SAPS were grossly negligent in the performance of their duties. Both the search for the plaintiff at Kings Beach and the subsequent investigation did not meet the standards expected of reasonable police officers.

It is not suggested that the search for the plaintiff nor the subsequent criminal investigation had to be perfect. That is clearly too high a standard from the police. The only requirement is that a reasonably diligent and skilful search and investigation had to be carried out.17 In my mind for the reasons that I have set out above, neither the ground search, air search nor investigation by W/O Andrews and W/O Madubedube was carried out with the diligence and skill required of a member of SAPS – the duty underpinned by the Constitution and to which its citizens are entitled to reply upon.

The Second Defendant, Brigadier Koll

The plaintiff alleges against the second defendant, Brigadier Koll, that he:

failed to “supervise” the members of the SAPS stationed at Humewood Police Station in their search for the plaintiff on the night of 9/10 December 2010.

gave the plaintiff an undertaking on 3 June 2011, that he would personally supervise the investigation of her complaints arising out of the incidents on 9 December 2010, which undertaking the Second Defendant failed to carry out adequately or at all.

The evidence was clear, however, that the second defendant was not even aware of the search during the night of 9/10 December 2010 and he certainly was at no stage in charge of that search.

Moreover, the evidence is overwhelming that that investigation of the plaintiff’s allegations of abduction and rape was carried out by a specialised unit (FCS) which did not fall under Brigadier Koll, but fell under the command of Colonel Engelbrecht at the time.

Brigadier Koll was clearly at no stage in charge of the investigation because FCS was. There is insufficient evidence to find that he made any undertaking to the plaintiff, and consequently no grounds for a finding of negligence against him.

The Third Defendant, W/O Madubelube

While I for the reasons above I have found that W/O Madubedube was negligent in the manner in which he conducted his investigation, I find that he was at all times acting in the course and scope of his employment and there is no reason to find against him in his personal capacity.

The Fourth Defendant, Sergeant Solomons

Insofar as the fourth defendant, Sergeant Adine Solomons is concerned, the plaintiff alleges that the fourth defendant:

failed to compile the initial identikit of the plaintiff’s abductor and rapist;

failed to display any, alternatively sufficient, skill and/or experience and/or knowledge in utilising the SAPS identikit (software) in attempting to compile an identikit of her abductor; and

failed to carry out her undertaking to return to “complete” the aforesaid compilation of an identikit.

Sergeant Solomons, who is now stationed at Worcester, refuted all these allegations in her evidence and she was not cross-examined at all. She testified that on the morning that W/O Madubedube was appointed as the investigating officer, he requested her to go to the plaintiff’s mother’s house in Port Elizabeth to compile the identikit and that she spent approximately 1½ hours with the plaintiff in order to do so. The resultant identikit compiled by her was as good as she could achieve with the assistance of the plaintiff.

When Sergeant Solomons learnt in February 2011 from W/O Madubedube that the plaintiff was dissatisfied with the compilation, she arranged for another identikit compiler, Sergeant Amanda Steenkamp in Johannesburg, to compile another identikit.