REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA

IN THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA

GAUTENG LOCAL DIVISION, JOHANNESBURG

CASE NO: 1675/19

|

1. REPORTABLE: NO 2. OF INTEREST TO OTHER JUDGES: NO 3. REVISED: YES / NO

DATE: SIGNATURE OF JUDGE:

|

In the matter between:

LLEWELLYN PALMER obo L P PLAINTIFF

and

ROAD ACCIDENT FUND DEFENDANT

JUDGEMENT

FLATELA J

[1] This is an action against the Road Accident Fund (hereinafter the Fund) instituted by Mr. Palmer in his natural and representative capacity of the Plaintiff, his minor son, “JL”, due to injuries sustained as a result of a motor vehicle accident which occurred about 23 April 2018. JL was 13 years of age at the time of the accident.

[2] The matter was allocated to me in the default trial court on 26 October 2022 in the virtual court for the determination of general damages, future loss of income, past and future medical expense.

[3] The plaintiff avers that the defendant is liable to compensate the plaintiff in the sum of R13 856 026 71 (Thirteen Million Eight Hundred and fifty-six thousand and twenty-three rand and seventy one cents).

Factual Background

[4] The accident occurred in the intersection between Commando Road and Springbok Road, Longdale, Johannesburg, Gauteng Province, between a vehicle with registration number KDB 700 GP (“the insured vehicle” driven by AM Mlilo “the insured driver”) and the minor who was a pedestrian at the time of the accident.

[5] JL was walking home from school with his twin brother and was about to cross the street but then he heard a hoot and stepped back into the Rea Vaya bus lane whereat a minibus taxi collided with him.

[6] He went immediately comatose at the scene. He was airlifted to Sandton Medi Clinic where he remained in the intensive care unit for approximately five weeks before spending another four weeks in the general ward. He then received four months of rehabilitation at Auckland Park Rehab Center. His Glascow Coma Scale1 was reportedly recorded between 3 & 6 /15.

[7] He sustained the following injuries:

A head injury with very serious high pressures in the brain. An MRI scan of the brain conducted on 4th May showed traumatic contusion and haemorrhage in the right temporal and bi-frontal regions;

A subdural haematoma was present in the right frontoparietal region; this was drained by Dr Bhoola;

A diffuse axonal injury of the brain involving the celebral hemispheres, basal ganglia, brainstem cerebellum and corpus callosum;

A depressed skull fracture (quoted by Dr H v D Bout);

A fracture of the right femur;

A fracture of the right tibia;

Haemopneumothorax;

A fracture of the right clavicle;

A devolving scalp injury;

A laceration of the right ear;

Multiple abrasions and lacerations.

[8] As a result, the Plaintiff suffered from the following injuries sequalae:

Brain damage – severe diffuse brain damage with severe intellectual deficits.

Motor problems – severe motor and balance problems.

Speech problems – severe speech problems. The speech problems stem from two types of speech problems, viz. a sever dysarthria because of motor control problems of his tongue and mouth; and dysphasia.

pseudo bulbar paralysis of the mouth, tongue, and swallowing mechanisms.

Personality change – very emotionally liable; sometimes aggressive with severe emotional control problems.

Bladder and stool control – sometimes incontinence of both bladder and stool control.

Walking ability – he cannot walk for too long, or without help. He is effectively, wheelchair bound.

Dexterity problems – he cannot write as he used to; struggles with pencil grip.

Right leg – is shorter than the left leg because of the femur and tibial fractures sustained in the accident.

[9] At the Auckland Park Rehabilitation Center, he received the following treatment: physiotherapy; occupational therapy; speech therapy, for no less than four months.

[10] The Plaintiff suffers from at least a 30% whole person impairment. The merits were conceded 100% by the Fund in favour of the Plaintiff’s proven damages, the Plaintiff claims from the Fund:

Past hospital and medical expenses – R1 660 354.71 (one million, six-hundred and sixty thousand, three-hundred and fifty-four rands, seventy-one cents);

Future loss of earnings – R9 165 669.00 (nine million, one-hundred and sixty-five thousand, six-hundred and sixty-nine rands);

General damages for pain and suffering, loss of amenities, disfigurement, and permanent disability – R3 000 000 (three million).

Evidence

[11] The Plaintiff was examined by several experts whose reports were confirmed by their affidavits filed in court. I agreed to consider the experts evidence on affidavits with election to call them to give oral evidence in the event I require clarification. Experts witnesses were available and on standby.

Personal circumstances of the Plaintiff and family background

[12] The Plaintiff’s father, Mr Palmer, testified on the personal circumstances of JL pre and post morbid.

Living Arrangements

[13] The Plaintiff lives in Johannesburg with him, his wife and JL’s two other siblings. He is one of non-identical twins. Their house is three bedroomed houses with one bathroom. It is bonded house. He shares a bedroom with his twin brother. The house is not wheelchair friendly.

[14] Mr Palmer stated that he was at work when he received a call to come to the scene of the accident. JL and his twin brother were in high school in grade 8 at the time of the accident. Mr Palmer started crying when describing the scene of the accident. He was advised not to describe the scene and the state of JL at the time of the accident but to give evidence on the pre-morbid and post morbid state of the minor child.

[15] He described him as follows:

He was active, independent, responsible, and more matured than his twin brother who is an introvert and reserved.

He was responsible, respectful, and disciplined, dutiful and did his home chores.

He was independent.

He was his own man.

Overall, he had normal childhood behaviors as can be expected of a teenager and presented with no psychological or physical problems.

Post Morbid

[16] He states that the Plaintiff emotional state has changed drastically. He describes him as four seasonal in a day, meaning that his emotional state changes many times in one day. It is a roller-coaster ride. He states that he has a good relationship with his brother, however he has a love-hate relationship with his eldest sister, meaning he fights with her for no reason. He does not sleep like normal people. He stays awake at night and has inconsistent sleeping patterns.

[17] He states that had it not been for the accident JL would be in grade 12 this year with his twin brother. He describes the Matric year as the most difficult year especially to his twin brother. His twin brother wanted JL to go with him to matric dance. His twin brother did not want to attend Matric ball without JL.

[18] In a normal day the Plaintiff wakes up, baths, eat, watches TV and movies on his laptop. He can read.

Financial Circumstances

[19] The Plaintiff’s father, Mr Palmer, is 39 years of age and has a grade 12 education. From 2012 to present date, he is permanently employed at Afrocentric Health as an IT specialist. From 2000 to 2008, he was permanently employed as a home loans consultant at ABSA Bank. He then became retrenched from this position. From 2009 to 2011, he was permanently employed at Sykes as a technical support call center consultant. He then became retrenched from this position.

[20] I enquired as to whether he was aware of the amount that is being claimed for damages on behalf of the minor child. He stated that he has no idea and that he did not want the Plaintiff to know because he did not want the plaintiff to start thinking about money. He explained that the plaintiff has many ideas.

Mrs. Palmers Testimony

[21] Mrs. Palmer, the Plaintiff’s mother testified that she is married to Mr Palmers in community of property, and they are living together with their children. JL was an independent child, more mature and he acted like a bigger brother to his twin brother and was very protective. On a normal day post morbid he wakes up, brush his teeth, bath, eat, reads books like children’s bible stories, play the play station and watch movies. His twin brother assists him with bathing as he prefers his twin brother to assist him when bathing. He reads newspapers and magazines. He attends therapy every week. He spends more time with his father. Overall, Mrs., Palmer testimony corroborated much of what was shared by Mr Palmer about their son, and it also corroborated that which they reported to the Plaintiff’s experts about his pre-morbid personality profile.

[22] Mrs. Palmer testified that she holds a grade 12 education and is 41 years of age. About her work history: (1) From 1999 to 2015, she was employed as an administration clerk in various departments of ABSA Bank. (2) As from 2017 to present date, she is employed as a student hairstylist as part of a three-year learnership. In this, Mrs. Palmer completed NQF level 2 and 3 training as a student hairstylist and plans to study further and complete NQF level 4. She also intends to write the trade’s test and qualify as a hairstylist. Once qualified Mrs. Palmer aspires to start and operate her own salon.

[23] Mrs. Palmer too also did not know how much was being claimed on behalf of Plaintiff.

[24] Before I go on the Plaintiff’s profile, expert reports, and awards I make under the heads of general damages, loss of earning capacity and past loss of medical expenses, I must interpose with a certain discomfort arising out of the Palmers’ testimony. Both Mr and Mrs. Palmer testified in Court that they did not know how much their attorney is claiming on behalf of their son. Mr. Palmer’s excuse is that he does not want the Plaintiff to form wild ideas about the money. Perhaps that makes sense in reference to the Plaintiff, but the same cannot be said about him nor his wife. After all, they, especially he, are the representative litigants on behalf of the Plaintiff.

[25] Unsettled by this testimony, I raised concerns with the Plaintiff’s counsel about this issue. Plaintiff’s counsel correctly so advised that Ms. Sonya’s Meistre who was present in court is better suited to address the court’s concerns, Ms. Meistre under oath advised the court that it is her not to disclose to her clients how much she claims for them. Her explanation was that when plaintiffs are informed of how much has been claimed initial because the initial summons are a wild guess. It is always the case that the summons may be amended after the reports of experts.

[26] She tells clients about the amount when there is an offer on the table . The other reason why the amounts are not disclosed earlier in litigation was to avoid conflicts and misunderstanding. If the amounts are disclosed earlier and the court makes the award, but the awarded money, after expenses, disbursements and fees is not what is eventually given to the plaintiff.

[27] Ms. Meister’s explanation does not make sense. Of course, clients, with no intimate knowledge of accounting detail and deductions that go into RAF awards are entitled to query and seek adequate explanation of the transactions. In an era where many plaintiff attorneys litigating in the RAF space have been suspended, struck off the roll and/or imprisoned for squandering monies held in their trust accounts due to plaintiffs, such vigilance by plaintiffs is to be encouraged and not circumvented by deliberate secrecy.

[28] In this matter, the plaintiff’s parents did not know at the final hearing of the matter how much the plaintiff is claiming for damages. How is it correct that Mr. Palmer as a legal representative of the plaintiff not know how much he is claiming for his minor son?

[29] This in my view is borderline unethical and leaves plaintiffs to vulnerability of being short-changed of their claims. I do not in any way suggest that Sonya Meistre Attorneys short-changes their clients, but that the firm’s practice to litigate and claim against the Fund, without the plaintiff’s knowledge of how much is being claimed on their behalf is worthy of rebuke and further attention by the Legal Practice Council.

Post-morbid profile

The Plaintiff’s experts’ reports

[30] The plaintiff was examined by the following experts:

a) Dr PH Kritzinger – neurologist, report dated 24 May 2019;

b) Dr H.E.T van der Bout – orthopedic surgeon, report dated 25 September 2019;

c) Professor LA Chait – plastic surgeon, report dated 17 February 2020;

d) Dr O guy – Speech, Language Pathologist and Audiologist, report dated 20 January 2020;

e) Ms R Macnab – educational and neuropsychologist, report dated 2 October 2019;

f) Dr B Wolfowitz – otolaryngologist (ear, noise, and throat doctor), report dated 27 January 2020. (No material and/or adverse clinical conditions were found by this expert upon examination of the Plaintiff. Therefore, their report shall not be discussed in this judgment.)

g) Dr J Levin – ophthalmologist, report dated 3 March 2020. (No material and/or adverse clinical conditions were found by this expert upon examination of the Plaintiff. Therefore, their report shall not be discussed in this judgment.)

h) Ms T Gidini – occupational therapist, report dated 6 February 2020;

i) Ms Jeannie van Zyl – industrial psychologist, report dated 15 March 2020.

Dr PH Kritzinger – Neurologist

[31] Dr Kritzinger testified that he is neurologist with 40 years of experience. He has examined the plaintiff and he is of the opinion that he is the worst case in about 900 patients he has examined in his career. He is severely brain damaged, and wheelchair bound with a severe speech problem.

[32] He stated that the Plaintiff sustained a very serious brain injury with traumatic contusion and hemorrhage in the right temporal and bi-frontal regions with a subdural heamatoma in the right frontal regions as well as a diffuse axonal hemorrhage in the brain, the brainstem and the cerebellum. This diffuse axonal injury involves the cerebral hemispheres, the basal ganglia, the brainstem and the cerebellum. There was also a corpus callosum.

[33] The Plaintiff also presented with upper motor neuron signs in his arms and legs with severe coordination and motor problems. Brisk reflexes in both arms and legs were noted; and so were bilateral Babinski responses. The cranial nerves showed some asymmetry of the face with less movement on the right-hand side. Further noted were severe impairments to swallowing and tongue movements with pseudo bulbar paralysis (this means a severe control of swallowing, speech, and other mechanisms in the mouth, soft palate and tongue).

[34] According to Dr Kitzinger, the Plaintiff has a 15% chance of developing post-traumatic epilepsy. Finally, he concludes that the Plaintiff’s longevity has been decreased by at least 6 to 7 years. He also suffers from the following deficits

27.1. He has severe intellectual deficit.

27.2. He has severe motor problems and balance

[35] He has reached maximum medical improvement.2

Dr H.E.T van der Bout – orthopedic surgeon

[36] Dr van der Bout testified that he examined the Plaintiff on 25 September 2019. He observed that has an abnormal gait, with weakness of the legs, especially the right leg. He was unable to stand long, walk for long. He is only able to walk on his own for about 25 meters. The Plaintiff is, effectively, wheelchair bound. The doctor also noted that there is also a mild weakness of the right upper limb, especially the elbow and wrist extension, as well as with his right-hand grip strength. He stated that he would probably be institutionalized later in life as his neurological injuries were irreversible. He made common cause with the opinion of Dr Kitzinger’s report.

Professor L.A Chait – plastic surgeon

[37] From Prof LA Chait’s report, the Plaintiff’s plastic surgeon, the following scars are noted:

Scarring on the scalp, right ear, supra sternal notch region, left chest, left side of the abdomen, supra pubic region, right lower thigh, both right and left knee and upper shin region.

[38] Prof Chait opines that although some of the Plaintiff’s scars could be improved by certain surgical procedures; however, the Plaintiff shall remain with permanent disfigurement.

Dr Odette Guy – Speech, Language Pathologist and Audiologist therapist

[39] Dr Guy clinical examination reports that the Plaintiff presents with a moderate to moderately severe dysarthria with a staccato pattern. This indicates he sustained an injury to the motor speech supporting areas of the brain. Because of this, the Dr Guy finds that the Plaintiff is not an equal, effective, nor an efficient communication partner. His dysarthria and apraxia of speech inhibits him from speaking in a manner that is intelligible to others. Fatigue will also worsen his speech intelligibility.

[40] In terms of his expressive language, Dr Guy found that the Plaintiff’s descriptive, narrative, comparative, and/or persuasive discourses had marked impairments in sequencing. He was however, reasonably productive, generating several ideas, but poor cohesion and coherence rendered his discourses to be of poor quality. This was stressed by overt limitations from his dysarthria, apraxia of speech, economy of effort, its slurred rate and agrammatism. Asymmetry of the face was also noted.

[41] In summary, Dr Guy concluded that the Plaintiff presents with a speech, language and communication profile that is characterized by dysarthria (with a staccato pattern), apraxia of speech and an expressive aphasia. He also has cognitive linguistic patterns that are characteristic of individuals that have suffered right frontal lobe injuries.

[42] He is furthermore likely to struggle with long conversations; or conversations that are more abstract and/or decontextualized (that is, not necessarily pertaining to events or people around him at the time). Added to this are high level language concerns, particularly with figurative interpretation of language, extrapolation of novel information from language, and generation of information using language.

[43] Dr Guy concludes that the ability to understand and produce oral and written language is essential for an individual’s success across a number of activities such as daily living, social participation, occupational undertakings as well as general wellbeing. The satisfactory maintenance of acquired language – both written and oral – and the comprehension thereof depends on the interactions of a number of sensory, perceptual, and cognitive processes.

[44] The Plaintiff’s motor speech, linguistic, cognitive linguistic, pragmatic, and cognitive communicative deficits represent a significant loss of amenities. He is not an effective nor efficient communicative partner. His ability to engage in meaningful interactions is impaired. He will rely on his communication partners to initiate repair. The Plaintiff’s loss of these amenities is permanent.

Ms R Macnab – Educational and neuropsychologist report

[45] The Plaintiff’s parents reported to Ms Macnab that since the accident the Plaintiff has had a drastic change of personality. It was reported that:

He is short-tempered and easily angered; he reportedly becomes angry with his sister even if she has done nothing to provoke him;

He is irritable and frustrated as he cannot enjoy or partake in his pre-morbid activities;

He becomes physically and verbally aggressive; he clenches his fists and directs his anger towards his sister; but sometimes, also towards his parents;

His mood fluctuates; sometimes he is withdrawn, sometimes he is not;

[46] The Plaintiff expressed ambition to play soccer professionally (he also expressed ambition to become a lawyer or pilot to Ms Gidini – the occupational therapist). He believes that in the future he will be successful and rich. To Ms Macnab, what all this demonstrates is that the Plaintiff has lack of insight to his condition.

[47] The test results from the Plaintiff’s psycho-emotional assessment show that he struggles with maintaining interpersonal relationships. The assessment findings revealed a significant degree of regression which was consistent with the account made by his parents of his mood swings, aggressiveness, and poor emotional control. Ms Macnab opines that this could also be attributable to language and communication difficulties as detailed in the report of Dr Guy.

[48] Ms Macnab found that his post-morbid cognitive skills and capabilities presents the following:

Has attention and concentration difficulties; he is distractible and struggles to complete a task;

Has memory problems, for example, he repeats himself when speaking as he would have forgotten that he had already said the information at hand;

His mental processing speed is notably slow;

He sometimes has difficulty understanding when spoken to, and has difficulty expressing himself.

[49] Ms Macnab reports that these cognitive impairments would translate as follows in a school environment:

Impaired cognitive control, attention and concentration difficulties and distractibility which will result in impulsive behaviour, lack of mental alertness, short-term auditory difficulties and the inability to focus without being easily distracted;

Impaired auditory memory and delayed recall which will affect his processing of information in short and/or to long term memory;

Impaired verbal expressive ability which will be difficulty verbalizing and expressing himself;

Impaired social reasoning and judgment – that is, poor understanding of social situations, resulting in inappropriate behavioral responses;

Impaired verbal abstract reasoning – that is, the ability to reason abstractly and logically, and to see relationships between various concepts;

Impaired numerical reasoning and problem-solving especially in terms of numerical stimuli which will in turn hinder his performance in mathematics;

Difficulty with working memory and mental tracking ability which will affect his ability to keep a track of problem in mathematics and other tasks

Impaired visual perception, spatial organization and visual concept ability which will affect his ability to see the relations between concepts and to visualize and integrated whole from separate components;

Impaired visual perceptual and conceptual abilities – that is, reflection of his contact with reality, knowledge and comprehension of familiar situations;

Impaired psycho-motor tempo – this is already evidenced by his slow working speed and will affect his ability to work within a time limit especially when writing exams or tests.

[50] In the main Plaintiff’s scholastic profile reflects significant learning difficulties. Ms Macnab found his reading ability to be in the level of a grade 3 learner, well below average. His spelling ability was found to be within below average range for his age and highest level of education. Tremors were also identified when writing, which resulted in shaky handwriting. As to his mathematical ability, it was found to be within the level of a grade 2 learner.

[51] Concluding on the Plaintiff’s academic capacity, or lack thereof, Ms Macnab makes note that although it is her opinion that the Plaintiff be placed in a school for learners with special needs, given the extent of his post-morbid profile and his brain injury, he will be unable to matriculate even with the appropriate intervention. This opinion is also shared by Dr Guy – the Speech, Language Pathologist and Audiologist. Dr Guy says that one of the most important tools imperative to the Plaintiff’s educational ability, that is language, is so impaired that this will slow his rate and progress.

GENERAL DAMAGES

[52] It is common cause that the plaintiff suffered serious injuries. Plaintiff claims an amount of R3 000 000 (three million rands) for general damages.

Legal principles applicable to claims of general damages

[53] In Van der Merwe v Road Accident Fund and Another3 Moseneke DCJ had the following to say about general damages:

The notion of damages is best understood not by its nature but by its purpose. Damages are “a monetary equivalent” of loss “awarded to a person with the object of eliminating as fully as possible [her or] his past as well as future damage.” The primary purpose of awarding damages is to place, to the fullest possible extent, the injured party in the same position she or he would have been in, but for the wrongful conduct. Damages also represent “the process through which an impaired interest may be restored through money.” To realise this purpose our law recognises patrimonial and non-patrimonial damages. Both seek to redress the diminution in the quality and usefulness of a legally protected interest. It seems clear that the notion of damages is sufficiently wide to include pecuniary and non-pecuniary loss and it is understood to do so ordinarily in practice.4

non-patrimonial damages, which also bear the name of general damages, are utilized to redress the deterioration of a highly personal legal interests that attach to the body and personality of the claimant. However, ordinarily the breach of a personal legal interest does not reduce the individual’s estate and does not have a readily determinable or direct monetary value. Therefore, general damages are, so to speak, illiquid and are not instantly sounding in money. They are not susceptible to exact or immediate calculation in monetary terms. In other words, there is no real relationship between the money and the loss. In bodily injury claims, well-established variants of general damages include “pain and suffering”, “disfigurement”, and “loss of amenities of life.5

it is important to recognise that a claim for non-patrimonial damages ultimately assumes the form of a monetary award. Guided by the facts of each case and what is just and equitable, courts regularly assess and award to claimants’ general damages sounding in money. In this sense, an award of general damages to redress a breach of a personality right also accrues to the successful claimant’s patrimony. After all, the primary object of general damages too, in the non–patrimonial sense, is to make good the loss; to amend the injury.6

Quantification of General damages

[54] When determining general damages Holmes J in Pitt v Economic Insurance Co Ltd7 said ‘[T]he court must take care to see that its award is fair to both sides – it must give just compensation to the plaintiff, but it must not pour out largesse from the horn of plenty at the defendant’s expense.’

[55] In the case of Protea Assurance Co Ltd v Lamb8 Potgieter JA stated that although the determination of an appropriate amount for general damages is largely a matter of discretion of the court, some guidance can be obtained by having regard to previous awards made in comparable cases; however, as stated by the learned Potgieter J in that case:

'... this process of comparison does not take the form of a meticulous examination of awards made in other cases in order to fix the amount of compensation; nor should the process be allowed so to dominate the enquiry as to become a fetter upon the Court's general discretion in such matters. Comparable cases, when available, should rather be used to afford some guidance, in a general way, towards assisting the Court in arriving at an award which is not substantially out of general accord with previous awards in broadly similar cases, regard being had to all the factors which are considered to be relevant in the assessment of general damages. At the same time, it may be permissible, in an appropriate case, to test any assessment arrived at upon this basis by reference to the general pattern of previous awards in cases where the injuries and their sequelae may have been either more serious or less than those in the case under consideration.'

Comparable cases

[56] Dosio AJ in Ndlovu v Road Accident Fund9 said that, ‘There is no hard and fast rule in considering past awards, as it is difficult to find cases on all fours with the one presently being considered.’ Therefore, the section below observes a general pattern of awards in cases involving injuries that are, as best as possible, comparable to those of the Plaintiff. To do justice to this task, I shall observe case comparisons going beyond just minors.

[57] Choles obo Anthony Tayler David v Road Accident Fund10 was awarded R1 200 000 in general damages where the Plaintiff, an 11-year-old minor was in an unconscious state when admitted to hospital, underwent neuro surgery and was in an induced coma in ICU for three weeks. He had suffered multiple fractures to the head and face, a degloving occipital injury, a fractured left patella and tibia. After discharge from hospital, he had to be referred to a facility for rehabilitation.

[58] In Webb v RAF11 the plaintiff sustained a fracture and T12/L1 fracture resulting in paraplegia, displaced radius and ulna fracture. The plaintiff was involved in the collision when he was 20 years old and had become wheelchair bound as a result of his injuries. The award for general damages was R1500 000.00

[59] In Megaline v Road Accident Fund12 the Court awarded R1 000 000 in general damages wherein the Plaintiff, an 11-year-old boy, then got injured whilst travelling with his parents. He sustained a head injury which led to him having to be admitted in a nursing home. He had profound neurological impairments and prominent irreversible disfigurement. The court held that his loss of amenities was profound.

[60] In the matter of Van Zyl v Road Accident Fund13, a 19-year-old male part-time law student sustained a severe head injury with multiple craniofacial impact on a severe traumatic brain injury. He also sustained serious orthopedic injuries with bilateral severe tibia/fibula fractures and multiple abrasions and bruises. A vegetative state persisted for weeks. He underwent treatment and rehabilitation of seven months. The Court awarded R850 000 in general damages.

[61] In determining an appropriate award in respect of general damages for and regard being had to the cases above, I am reminded of the matter of Road Accident Fund v Marunga14 where the SCA stated that, in comparison to a young person as opposed to an older person who sustains similar injuries, the older the plaintiff is, the lower the award of general damages. It should therefore follow that the same is true the other way around.

[62] Prior to making the award, I should also say that I have had the pleasure of meeting the Plaintiff in Court. I observed he has slurred speech, but however did not present as certainly the worst case ‘ever seen in about 900 patients.’ To me, the Plaintiff presented as an intelligent young man, and about his bearings. He knew his name, he knew his parents name, he knew, in address detail, where he lived. And in conversation with him, I complimented that he is a handsome young man. His response was, “people often say that about me, but I don’t see that in myself”. Understandably, his self-image has been affected. I asked him whether he is the oldest twin, he responded, “I don’t know. I came out first, but people say that the twin that comes out last is the oldest twin”. I asked him to paint for me his typical day, he told me that he wakes up, baths – can do this on his own, but sometimes with the help of his brother; makes his bed – this too he can do on his own; and be on his laptop. I propped on what he watches in his PC, and he told me that he searches for property. He wants to buy a house – I assume, this in anticipation of a successful claim; bear in mind that his father did say the Plaintiff has many ideas.

[63] Having considered the evidence, comparative case law, and the Plaintiff’s presentation, I am view that an award of R1 850 000 in general damages is appropriate in the circumstances.

Loss of Earnings

[64] Much of Ms. Gidini’s, the Plaintiff’s occupational therapist; report clinical assessment findings are already reflected and/or alluded to in the previous expert reports. Therefore, I shall not burden this judgment with repetitive information, save to extract her conclusion that given the severity of the Plaintiff’s physical, cognitive, and psychosocial limitations, all recommended interventions are of a rehabilitative nature, and even therein, improvement is not anticipated. She concludes that he is unemployable in the open labour market.

Ms Jeannie van Zyl – Industrial psychologist

[65] Ms van Zyl’s report supports her postulated pre and post accidental scenarios of the Plaintiff’s future potential with much reliance from the following opinion in Ms Macnab report:

‘With regard to premorbid scholastic/academic history … he was enrolled for grade 1 at T.C Esterhuysen Primary School in 2011. He progressed from grade 1 to 7 without any failures, and the available school reports indicated that he performed predominantly above the grade average. Landen started high school in 2018 at RW Fick Senior Secondary School, and he was enrolled in grade 8 at the time of the accident in April 2018… With regard to pre-morbid intellectual functioning and educability, a number of factors must be taken into consideration in determining Landen’s pre-morbid educability. These include family educational history, both of Landen’s parents completed grade 12 as their highest level of education. Furthermore, both his siblings were in age appropriate grades, with no failures reported. As previously noted, there were no delays in Landen’s early childhood development… Therefore, with consideration to all the information available to the writer, as described above, it is more likely that Landen was probably a high average learner prior to the accident. As such, he would in all likelihood have coped adequately with the academic requirements of mainstream school, up until and including grade 12 with the probability of furthering his studies with a post-matric qualification, such as a diploma (NQF 6) or possibly a bachelor's degree (NQF 7), depending on family support and financial ability.’

[66] Taking cognizance of Ms Macnab’s opinion, van Zyl postulated two broad scenarios in order to create benchmarks for the quantification of the Plaintiff’s earning potential.

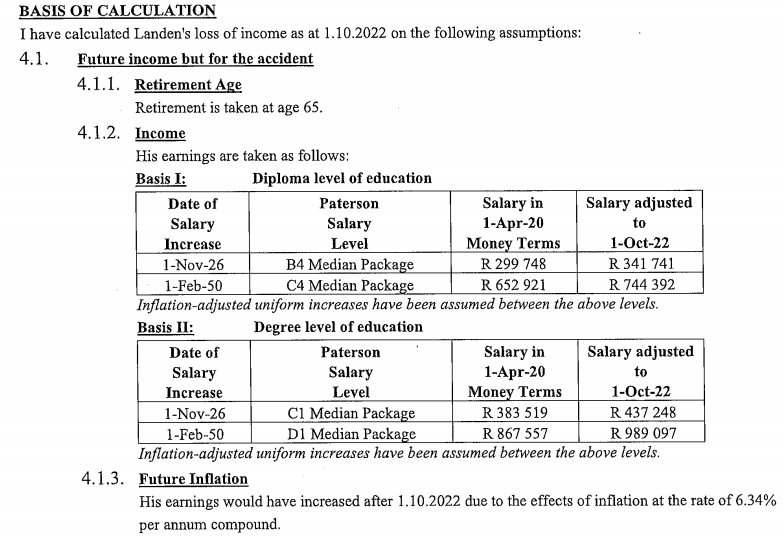

[67] In scenario 1 the Plaintiff would have probably completed grade 12 and a diploma (NQF 6) qualification. After completing grade 12, the Plaintiff probably have enrolled at a tertiary institution and have studied three years full time towards a diploma or similar NQF 6 qualifications in a career of his choice. After completing his tertiary studies, Plaintiff would probably have entered the labour market. He would probably have spent an average of eight to twelve months (average ten months) in search of employment. Plaintiff’s remuneration would probably have constituted a basic salary and employee benefits in line with the formal employment sector.

[68] Plaintiff would probably have entered the labour market at Paterson B4 (median guaranteed package of R 299, 748.00 per annum in April 2020 terms). With in-service training and work experience, he probably would have progressed to employment at Paterson C4 (median guaranteed package of R652, 921.00 per annum in April 2020 terms).

[69] In this scenario, it is recommended that the age 45 be regarded as the Plaintiff's career ceiling and that straight line increases be applied up to the retirement age 65.

[70] In scenario 2, Plaintiff would possibly have completed a degree or a similar NQF 7 qualification in a career of his choice. After completing his tertiary studies, Plaintiff would probably have entered the labour market. He would probably have spent an average of eight to twelve months (average ten months) in search of employment. Plaintiff’s remuneration would probably have constituted a basic salary and employee benefits in line with the formal employment sector.

[71] Plaintiff would probably have entered the labour market at Paterson C1 (median guaranteed package of R 383, 519.00 748.00 per annum in April 2020 terms). With in-service training and work experience, he probably would have progressed to employment at Paterson D1 (median guaranteed package of R867, 557.00 per annum in April 2020 terms).

[72] In this scenario, it is recommended that the age 45 be regarded as the Plaintiff's career ceiling and that straight line increases be applied up to the retirement age 65.

[73] Taking cognizance of all the available information and of her own assessment, Ms van Zyl concluded that the Plaintiff’s learning, work and earning capacity has probably been significantly and permanently compromised by a constellation of neuropsychological/cognitive, neuro-physical, communication and psychological sequalae deficits associated with the brain injury. Therefore, the writer agrees with Dr van den Bout, Dr Kritzinger, Dr Guy and Ms Gidini that the Plaintiff is rendered permanently unemployable in all capacities, both informal and formal sector.

[74] In conclusion, it is to be said that the Plaintiff has probably suffered a total loss of earnings which should be calculated from the date he would have entered the labour market until retirement.

[75] From these assumptions, the Plaintiff’s actuaries drew the following calculations:

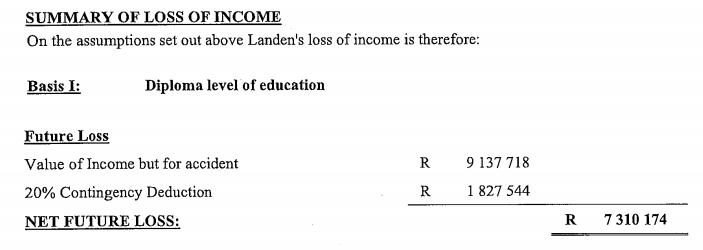

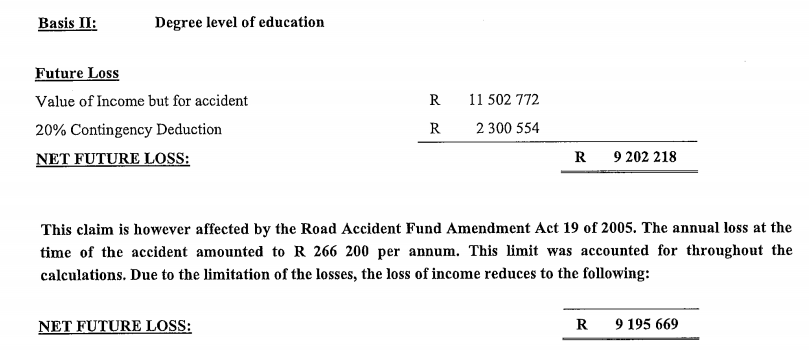

[76] And after suggesting a pre-morbid 20% contingency deduction, their calculations came to this summary:

Discussion

[77] The traditional principle and rationale guiding for restituting loss of earning capacity was expressed in Dippenaar v Shield Insurance Co Ltd15 per Rumpf JA where he held that:

‘In our law, under the lex Aquilia, the defendant must make good the difference between the value of the plaintiff's estate after the commission of the delict and the value it would have had if the delict had not been committed. The capacity to earn money is considered to be part of a person's estate and the loss or impairment of that capacity constitutes a loss, if such loss diminishes the estate.

This was the approach in Union Government (Minister of Railways and Harbours) v Warneke 1911 AD 657 at 665 where the following appears:

"In later Roman law property came to mean the universitas of the plaintiff's rights and duties, and the object of the action was to recover the difference between the universitas as it was after the act of damage, and as it would have been if the act had not been committed (Greuber at 269)…”’

[78] The approach to determining loss of earnings and applicable contingencies, was recently explained by the Supreme Court of Appeal in Road Accident Fund v Kerridge16 wherein it said:

‘[40] Any claim for future loss of earning capacity requires a comparison of what a claimant would have earned had the accident not occurred, with what a claimant is likely to earn thereafter. The loss is the difference between the monetary value of the earning capacity immediately prior to the injury and immediately thereafter. This can never be a matter of exact mathematical calculation and is, of its nature, a highly speculative inquiry. All the court can do is make an estimate, which is often a very rough estimate, of the present value of the loss.

[41] Courts have used actuarial calculations in an attempt to estimate the monetary value of the loss. These calculations are obviously dependent on the accuracy of the factual information provided by the various witnesses. In order to address life's unknown future hazards, an actuary will usually suggest that a court should determine the appropriate contingency deduction. Often a claimant, as a result of the injury, has to engage in less lucrative employment. The nature of the risks associated with the two career paths may differ widely. It is therefore appropriate to make different contingency deductions in respect of the pre-morbid and the post-morbid scenarios. The future loss will therefore be the shortfall between the two, once the appropriate contingencies have been applied.

[42] Contingencies are arbitrary and also highly subjective. It can be described no better than the oft-quoted passage in Goodall v President Insurance Co Ltd 1978 1 SA 389 (W) where the court said: “In the assessment of a proper allowance for contingencies, arbitrary considerations must inevitably play a part, for the art or science of foretelling the future, so confidently practiced by ancient prophets and soothsayers, and by authors of a certain type of almanack, is not numbered among the qualifications for judicial office.”

[43] It is for this reason that a trial court has a wide discretion when it comes to determining contingencies. An appeal court will therefore be slow to interfere with a contingency award of a trial court and impose its own subjective estimates.

[44] Some general rules have been established in regard to contingency deductions, one being the age of a claimant. The younger a claimant, the more time he or she has to fall prey to vicissitudes and imponderables of life. These are impossible to enumerate but as regards future loss of earnings they include, inter alia, a downturn in the economy leading to reduction in salary, retrenchment, unemployment, ill health, death, and the myriad of events that may occur in one's everyday life. The longer the remaining working life of a claimant, the more likely the possibility of an unforeseen event impacting on the assumed trajectory of his or her remaining career. Bearing this in mind, courts have, in a pre-morbid scenario, generally awarded higher contingencies, the younger the age of the claimant. This court, in Guedes, relying on Koch's Quantum Yearbook 2004, found the appropriate pre-morbid contingency for a young man of 26 years was 20% which would decrease on a sliding scale as the claimant got older. This, of course, depends on the specific circumstances of each case but is a convenient starting point. In quantifying the monetary value of the loss of earning capacity, the court must remember that the case depends on its own facts and circumstances, as well as the evidence placed before the court by the plaintiff.’

[79] For the mathematical approach which is also called the actuarial approach it is a well-established practice that where the plaintiff suffers a permanent impairment of earning capacity, the proper and effective method of assessing past and future loss of earnings is as follows:17

a) To calculate the present value of the income which the plaintiff would have earned but for the injuries and consequent liability;

b) To calculate the present value of the plaintiff’s estimated income, if any, having regard to the disability;

c) To adjust the figures obtained in the light of all the relevant factors and evidence obtained and by applying contingencies;

d) To subtract the figure contained under (b) from that obtained

under (a).

[80] But what happens if the Plaintiff was a child at the time of the injury? How are we to calculate loss of earning capacity? In Roxa v Mtshayi18 Corbett JA was vexed with exactly this question when he said that:

‘While evidence as to probable actual earnings and probable potential earnings (but for the injury) is often very helpful, if not essential, to a proper computation of damages for loss of earning capacity, this is not invariably the case. In the present instance the imponderables were vast. The Court had to consider the position of a young child struck down almost in infancy. It was virtually impossible to foresee what he would do in life or to foretell what he would have done had he not suffered the injury. As to the actual future, no one can say what work he will be able to carry out after he leaves school and later when he becomes an adult; what effect his disabilities and the possibility of behavioral problems will have upon his employment and employability; whether he may not end up in some form of institution, and so on. As to the potential future, he was so young when the injury occurred that any enquiry as to what type of working career he might have followed must amount to pure speculation. When one further considers that the working period under consideration stretches some 30 or 40 years into the future, it becomes clear that any attempt at an actual calculation of loss of future income would be a fruitless exercise. The trial Judge took a broad view of the situation and awarded globular amount which he considered appropriate in the circumstances to compensate BoyBoy for all that he had lost including diminished earning capacity. I remain unpersuaded that this was an incorrect approach.’

[81] In Goodall v President Insurance 19 the Court adopted the approach of the so-called sliding scale of ½ % per year to retirement age in the ‘but for’ scenario – i.e. 25% for a child, 20% for a youth and 10% in middle age. In the ‘but for’ scenarios the Road Accident Fund usually agrees to deductions of 5% for past loss and 15% for future loss – the so-called “normal contingencies”.

[82] The Plaintiff was in high school in grade 8 at the time of the accident. His grade 7 report of the previous year (as well as his other reports of from primary school) reflect that the Plaintiff was doing well receiving between 70% and 80% on average. Since the accident he never went back to school. The Plaintiff’s twin-brother is still at school. He is in grade 12 and has never failed a grade. He too is doing well at school.

[83] I am mindful that none of the Plaintiff’s parent’s hold a higher education degree. (Their employment history is detailed above, and I shall not repeat it here.) However, that does not mean the Plaintiff would not have progressed further than his parents. Indeed, it is observed that generation Z20is doing far better than their parents. There are now such resources such as the National Student Financial Aid Scheme which provides an access gateway to higher education. I also take note that his eldest sister has Matric and is doing internships. Ms. van Zyl’s projections say that in scenario one, the Plaintiff would have probably attained a Diploma or some other similar qualification. So, it is on this basis that I make the award of loss of earnings and apply appropriate contingencies thereto.

[84] Having considered all the evidence it is my considered view that but for the accident, the plaintiff would have attained a Diploma, therefore scenario 1 with 25% post morbid calculations is the is most appropriate when calculating the plaintiff’s loss of earnings.

ORDER

[85] In the circumstances, the following order is made:

1. Default judgement is granted against the defendant in favour of the plaintiff as follows

1.1. Defendant to pay Plaintiff the sum of R10 363 643.21 (Ten million, three hundred and sixty-three thousand, six hundred and forty-three rand and twenty-one cents) in delictual damages in one interest free installment within 180 days from the date of order as follows

1.1. Future loss of income R6 853 288.50

1.2. General damages R1 850 000.00

1.3. Past medical and hospital expenses R1 660 354.71

2. Payment to be made in the following bank account:

Name of account holder: SONYA MEISTRE ATTORNEYS

Bank name: STANDARD BANK

Branch name and code: ALBERTON (01234245)

Account number: 020651864

Type of account: Trust Account

3. The attorneys for the plaintiffs (Sonya Meistre Attorneys) are ordered:

3.1. to cause a trust (“the Trust”) to be established within three months of this order in accordance with the provisions of the Trust Property Control Act, Act 57 of 1998 (as amended) in respect of the minor; and

3.2. to pay all monies held in trust by them for the benefit of the minor to the Trust.

4. That the moneys paid into the trust account is awarded as follows:

4.1. PALMER LADEN JAMAAL R8 703 288.50

5. The trust is to be created for the benefit of the minor, and must provide as follows:

5.1. that the minor is to be the sole beneficiary of the trust, with a division of the funds as follows:

5.1.1. PALMER LADEN JAMAAL R8 703 288.50

6. For the nomination of LEANE EDWARDS, an employee of Absa Trust Limited, and as such a nominee of Absa Trust, as the first trustee;

7. For the nomination of JEAN VOSLOO an executive of Liberty as the second trustee;

8. For the nomination of LLEWELLYN JERMAINE PALMER, the biological father of the minor as the third trustee;

9. That the Trust Deed marked X is made an order Court.

10. The Defendant pays the Plaintiff’s taxed or agreed party and party costs on the High Court scale up to the date hereof, including the reasonable costs incurred to obtain payment of same. Such costs to include the costs of 25 October 2022; 26 October 2022 and 27 October 2022 and all reserved costs.

11. Such costs to include all travelling costs, including counsel’s costs, on the prescribed AA tariffs.

12. Plaintiff shall serve Notice of Taxation on Defendant’s attorneys of record.

13. The Defendant will be allowed 180 (one hundred and eighty) days after date of taxation for payment of taxed amount.

14. If no payment has been made within 180 (one hundred and eighty) days as mentioned above, the agreed amount of costs or allocated will bear interest at the prescribed rate from the date of agreement or date of allocator as the case may be, up to the date of final payment.

15. The aforementioned costs, as far as experts and counsel are concerned, shall further include and be limited to the following:

15.1. The reasonable taxed or agreed reservation, consultation and preparation fees, if any, and cost of the reports of:

a) Dr. Kritzinger (Neurologist) ;

b) Dr. Van Den Bout (Orthopaedic surgeon) and RAF4;

c) Dr Odette Guy (Speech; language and audiologist therapist);

d) Dr Brian Wolfowitz (Ear Nose and Throat Specialist);

e) Dr Jonathan Levin (Ophthalmologist);

f) Rosalind Macnab (Educational psychologist);

g) Prof L Chait ( Plastic surgeon) and RAF4 form;

h) Maria Georgiou (Occupational therapist);

i) Jeannie Van Zyl (Industrial psychologist)

j) Gerard Jacobson (Actuary)

16. The reasonable taxed or agreed fees of counsel.

17. The reasonable taxed or agreed fees of the curator ad litem.

______________

FLATELA L

JUDGE OF THE HIGH COURT

This Judgment was handed down electronically by circulation to the parties’ and or parties representatives by email and by being uploaded to CaseLines. The date and time for the hand down is deemed to be 10h00 on 07 December 2022

Counsel for plaintiff: Adv N Pather Moodley

083 782 5692

Attorneys for the plaintiff: Sonya Meistre Attorney

State attorney for defendant: Phindile Makatin

072 452 7012

1 Glascow Coma Scale is used to measure a person’s level of consciousness following a traumatic brain injury. Here I averaged the Plaintiff’s GCS between 3 & 6/15 because some of his experts report it to have been 6/15 whereas others report it at 3/15. The difference is immaterial and negligible as common between the experts is that the Plaintiff went immediately comatose upon impact and laid so for some months thereafter.

2 This is a state when one reaches, in no less than two years, where it can be clinically expected that their condition post injury cannot improve anu further. The condition may deteriorate, but not improve. So, it is the same as saying one has healed, in whatever form, including of deterioration that healing may look like

3 Van der Merwe v Road Accident Fund and Another (CCT48/05) [2006] ZACC 4

4 Ibid, para 37

5 Ibid, para 39

6 Ibid, para 41.

7 Pitt v Economic Insurance Co Ltd Pitt v Economic Insurance Co Ltd 1957 (3) SA 284 (D) at 287E–F

8 Protea Assurance Co Ltd v Lamb 1971 (1) SA 530 (A) at 535H-536A

9 Ndlovu v Road Accident Fund (2018/28182) [2021] ZAGPJHC 526, para 19

10 Choles obo Anthony Tayler David v Road Accident Fund 21245/2018

11 Webb v RAF (2203/14) [2016] ZAGPPHC 15

12 Megaline v Road Accident Fund [2007] 3 ALL SA 531 (W)

13 Van Zyl v Road Accident Fund 2012 (6A4) QOD 138 WCC

14 Road Accident Fund v Marunga 2003 (5) SA 164 (SCA)

15 Dippenaar v Shield Insurance Co Ltd 1979 (2) SA 904 (A), para 9.

16 Road Accident Fund v Kerridge 2019 (2) SA 233 (SCA) at paras [40]—[44]

17 The Quantum of Damages, vol 1, 4th edition by Gauntlett at page 68; Southern Insurance

Association Ltd v Bailey 1984 (1) SA 98 (A) at 113 F – 114E

18 Roxa v Mtshayi 1975 (3) SA 761 (A) at 769 G - 770 A

19 Goodall v President Insurance 1978 1 SA 389 (W)

20 Born between 1997 and 2012