REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA

IN THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA

GAUTENG DIVISION, PRETORIA

CASE NO: 42822/2021

(1) REPORTABLE: NO (2) OF INTEREST TO OTHER JUDGES: NO (3) REVISED: NO 20 October 2022__ _________________ Date Signature

In the matter between:

ESKOM HOLDINGS SOC LIMITED Applicant

and

SISU SOMHAMBI ELECTRICAL CONSTRUCTION CC First Respondent

DANIEL MNISI Second Respondent

JUDGMENT

DE VOS AJ

Introduction

[1] The parties request the Court to resolve a dispute regarding the interpretation of a servitude. The parties agree that there exists a servitude in favour of Eskom on the respondents’ property. The parties agree that the purpose of the servitude is to permit Eskom to erect electrical towers and an overhead powerline. The parties agree the width of the servitude is 55 meters and that the respondents cannot build on the 55 meters.

[2] The parties' disagreement is from where to calculate the 55 meters. Eskom contends that the 55 meters start from the “center line of the powerline.” This means that the respondents cannot build 55 meters from the center line of the powerline. Eskom calculates the starting point of the servitude to be the center line of the powerline.

[3] The respondents contend that the total width of the servitude is 55 meters, 27.5 meters on either side of the center line. This means the respondents cannot build 27.5 meters on either side of the center line of the powerline. The respondents contend the servitude straddles the center line of the power line.

[4] The dispute the Court has to determine is whether the 55 meters is calculated from the center line of the powerline or whether the 55 meters straddle the center line, which results in a servitude of 27.5 meters on either side of the center line of the power line.

[5] Whilst the parties are only 27.5 meters apart, the determination of the dispute has weighty consequences for both parties. The respondents have built a hotel on its property. The hotel consists of twenty-two rooms, a spa, cinema, double story hall, restaurant, three conference halls, amphitheatre building and ancillary hotel facilities. The hotel construction is near completion. It cost of approximately R 500 000 000.00. If Eskom is correct in its interpretation then parts of the hotel encroaches on the servitude and has to be demolished.

[6] Eskom requires the servitude to erect electrical towers, as part of the Kusile-Lulamisa Powerline which forms part of the Kusile integration scheme to evacuate electrical power from the Kusile Power Station in order to strengthen the network in the norther part of Johannesburg. The project is known as the Kusuile-Lulamisa 400kV-Setion A Project. Eskom pleads that this is a high priority project of the national government.

[7] The respondents have raised several points in limine. The Court dismisses the points in limine. The points are dealt with, conveniently and unconventionally, at the end of this judgment.

[8] The case turns on an interpretation of the Option Agreement and the Deed of Servitude.

The option and deed

[9] The events leading to the registration of the servitude are common cause. In December 2010 Eskom concluded a written option to acquire a servitude with the previous owner.1 The option provides, in essence, for a servitude of 55 meters in width and that Eskom would acquire the option to register a servitude in general terms. The option provides Eskom with the right to conduct electricity over the property with one above ground powerline.2 The option provides in clause 3 that the owner’s property use is limited. The provision is central to the dispute and provides that the owner may not build within 27.5 meters of the center line of the of the powerline.3 The Afrikaans text of the option states that the owner is prohibited from building 27.5 from the "hartlyn" of the powerline. This has been translated, without dispute, to be the center line of the powerline.

[10] The option provides for:

a) A servitude for Eskom extending 55 meters in width;

b) To build only one powerline; and

c) A prohibition for building within 27.5 meters from the heartline of the powerline.

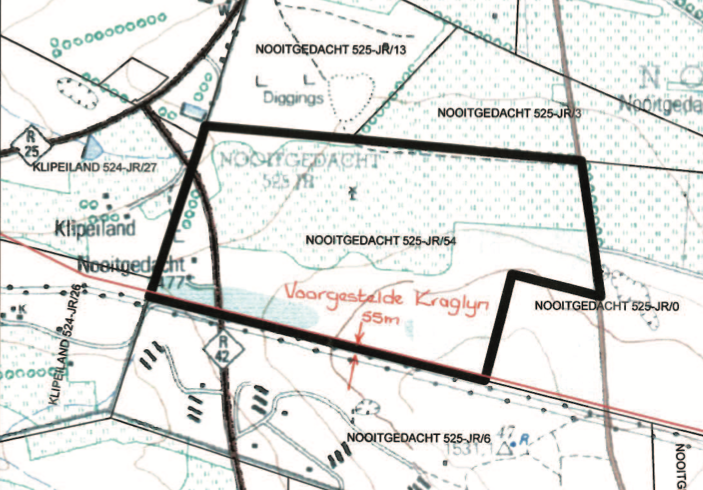

[11] Attached to the option is a sketch plan. The sketch plan indicates the route of the proposed powerline with arrows pointing towards the middle of the line with 55 m marked next to the arrows. The sketch is replicated at the end of the judgment.

[12] On 30 August 2011 Eskom exercised the option. Eskom registered the Notarial Deed of Servitude. The relevant part of the deed repeats the wording in the option in which it is stated that the owner of the property may not build within 27.5 meters from the centre line of the servitude.

[13] The parties agree that the determination of the servitude dispute is to be resolved with reference to the option and the deed.

Interpretation of the Option and Notarial Deed

[14] The principle, as old as Voet's writings, is that servitude, being something odious should be interpreted restrictively.4 An imprecise servitude must always be interpreted so that the servant tenement is less burdened.5 The Court must give a plausible interpretation of a servitude and must take into account the wording, surrounding circumstances,6 nature, extent and content of the agreement which created the servitude).7

[15] Eskom makes several arguments as to how the option and deed must be interpreted. Eskom contends that the agreement between Eskom and the previous owner refers to a width of separation distance of 55 meters. Indeed the option does have a one liner where it states: width 55 meters. Eskom invites the Court to conclude that this means, clearly and unambiguously, that the width refers to the wide range distance from the centre of the powerline.8

[16] The use of the word width can only mean, what it ordinarily means, from one end to the other. The width of an object describes its extent, not its location. In fact, referring to the width of something as 55 meters gives one no indication at all of its location. One cannot infer the location of a thing, based solely a description of its width. The interpretation Eskom contends for is at odds with the ordinary and grammatical meaning of the word "width".

[17] Eskom contends that the ordinary meaning must mean that “the width was meant to be attributed its ordinary meaning, which is the measurement from the centre line of the powerline towards the property”.9 There is nothing in the ordinary meaning of the word width that means from the center line of the powerline towards the property. In fact, Eskom has to add the words "from the center line of the powerline towards the property" for the width to have this meaning. The interpretation Eskom contends for requires reading words and meanings into the word "width" which does not appear in the documents nor can it be inferred from the ordinary use of the word "width". Plainly, there is nothing in the language of the documents10 that supports Eskom's interpretation.

[18] In addition, the interpretation Eskom contends for is at odds with the express wording of the option and deed. Both these documents have a critical and identical clause. Clause 3.1, of both the option and the deed, indicates that the owner may not build within 27.5 meters from the centre line of the powerline. If one takes 27.5 meters on either side of the heartline, one achieves a servitude with a 55 meters width. Clause 3.1 contemplates a servitude with a width of 55 meters split on either side of the heartline of a powerline means the servitude runs 27.5 meters on either side of the heart line of the powerline. The only manner in which one achieves a 55 meter wide servitude, which is 27.5 meters on either side of the powerline, is by measuring 55 meters from the heartline of the powerline.

[19] Eskom's interpretation in fact results in a servitude which is 82.5 meters wide, not 55 meters. Eskom contends that the servitude is 55 meters in width and that the starting point of the measurement must be the heartline of the powerline. Clause 3.1 prohibits building 27.5 meter on either side of the heartline. If the owner cannot build 27.5 on either side of the centre line and the servitude is 55 meters measured from the centre line, then the servitude area is in fact 82.5 wide. Eskom's interpretation contradicts the option and the deed.

[20] Eskom contends that the respondents interpretation that 55 meters be split on either direction of the powerline is "not apparent form the wording of the agreement".11 The Court finds it obvious in the deed that the 55 meters must be split on either side of the powerline because of the prohibition against building 27.5 meters on either side of the centre line of the powerline. Not being able to build 27.5 meters on either side of the powerline is exactly what happens when 55 meters is split on either side of the powerline.

[21] Eskom contends that the respondents’ interpretation is absurd as the other side of the tower falls on the Nooitgedacht 525 JR/6 which is a different property. Eskom contends that if the respondents’ interpretation is correct then Eskom ought to have concluded a servitude agreement with the owner of Nooitgetdacht 525 JR/6 for the 27.5 meters which falls within its property.12 The Court has not been provided with a factual basis for this allegation.13 The Court cannot make a finding based on a fact not pleaded. In any event, even if this was before the Court it would not be absurd to suggest that perhaps a mistake had been committed.

[22] The last of Eskom's arguments is that it has provided several expert opinions that supports its position, whilst the respondents have provided none.14 It is incorrect for Eskom to contend that the respondents have provided no expert reports. The respondents did in fact present an expert opinion.15

[23] In any event, Eskom's expert reports must be considered in context. Eskom obtained a report from Mr Sipho Tshabalala, a land surveyor employed by Eskom.16 Mr Tshabalala does not engage with the core issue before this Court, where the calculation of the 55 meters must start. Regardless, Eskom's summary of Mr Tshabalala's conclusion is that "the part servitude area on which the applicant seeks to construct its electric towers are far removed from the buildings." Mr Tshabalala's conclusions undermines Eskom's position. Mr Tshabalala's actual report concludes that “the proposed powerline has been pegged as per the signed option sketch and therefore Tower 70 is in the correct position”.17 It does not appear that Mr Tshabalala's expert opinion was sought on the issue directly before this Court.

[24] Eskom then appointed an independent land surveyor Mr Maukele of AbsoluteGeo.18 Mr Mafukele’s report does not assist in determining the question before the Court. Worse, Mr Mafukele refers to an old and new servitude line. This is concerning as the option limits the servitude to permitting Eskom to construct only one powerline.

[25] Eskom has disavowed reliance on the diagram of the Surveyor-General. The diagram does factually exist, regardless of Eskom's position. However, even if the Court were to have regard to the diagram, it does not assist. It does not address the question before the Court. Also, the diagram is not explained. To the extent that there is an explanation, it does not come from the office of the Surveyor-General, but is Eskom's deponent explaining the diagram. No basis for the deponent's authority to depose to these facts have been set out.

[26] None of the expert opinions presented by Eskom set out what their instructions was, what they considered and the basis of their conclusion. It in fact appears as if expert opinions considered the question where Eskom needs to erect a powerline. They did not engage with or assist the Court with interpreting the option and the deed. Attached to the deed is a diagram which sets outs the placement of the powerline and indicates with arrows how its width is to be calculated. The diagram is replicated at the end of this judgement. None of Eskom's experts engaged with this. In addition, the Court has not been provided with a basis to properly weigh and consider these expert reports. In MV Pasquale Della Gatta the Supreme Court of Appeal held that the court must first consider whether the underlying facts relied on by the witness have been established on a prima facie basis, if not then the expert's opinion is worthless because it is purely hypothetical. If so, then the opinion can be disregarded. Even if the facts had been established, the Court has to be put in a position to examine the reasoning of the expert and determines whether it is logical in the light of those facts and any others that are undisputed or cannot be disputed. Again, the Court has not been provided with this reasoning.19 The Court has also not been provided with the facts on which the experts based their conclusions.

[27] Contrary to Eskom's experts, the respondents' expert provided a helpful and relevant opinion. The respondents' expert, Mr Marambire explains20 that -

a) In the servitude sketch on page 8 of the option there is a red line pointing in and the other red line pointing out.

b) The sketch depicts a red line inside the boundary of the land which on the notes is indicates as a "proposed route of the 1 x 400 kv transmission line indicated in red". The redline is the center line of the powerline hence it has 27.5 m on both sides of the center line.

c) There is a distance of 55 m depicted next to the arrows pointing in and out. This indicates that 55 m must be shared along the redline "which makes it 27.5 m on both sides of the redline".

[28] Mr Marambire dealt with the question posed to the Court. Mr Marambire has engaged with the option and the deed and explained its reasoning to the Court. The expert opinion of Mr Marambire is the only logical and plausible interpretation of the option and the deed.

[29] The Court must give a plausible interpretation of a servitude and must take into account the wording, surrounding circumstances,21 nature, extent and content of the agreement which created the servitude).22 The only plausible interpretation is one where the 55 meters is split down the middle of the powerline which results in a limitation of the owner's right to build for 27.5 meters on either side of the powerline.

[30] Eskom, meekly in four paragraphs in its written submissions requests the Court to alter the route of the servitude. The Court has not been presented with any basis to do so. The relief referred to has not been sought, no statutory or common law basis has been presented for the argument. No facts provided. Plainly, no case for this relief has been made out. Whilst there is a public interest that may be served by altering the route, the public will not be served if Eskom is permitted to obtain relief for a case not made out in the papers.

Point in limine 1: Jurisdiction

[31] The respondents contend that this Court lacks the jurisdiction to determine this dispute by virtue of the provisions of 29 of the Land Survey Act, 1997. The Land Survey Act provides a process to resolve a dispute regarding a beacon or boundary of land which has been determined by survey. The process in short, permits the owner or the Surveyor-General to request that an agreement between the owners involved in the dispute be accepted. If someone refuses to sign the agreement, then subsection 29(5)(a) permits the Surveyor-General to refer the matter to arbitration.

[32] Eskom, in an attempt to resolve the impasse, requested the Surveyor-General to draw a diagram dealing with the servitude. The respondents contend that the fact that the Surveyor-General has drawn this diagram means that the matter falls to be decided by section 29(5)(a) of the Land Surveys Act which requires the dispute to be referred to arbitration. In this way, contends the respondents, the Court’s jurisdiction is ousted.

[33] The Court is not persuaded that the respondents have, in this case, pleaded the necessary facts to indicate that section 29 is at play. The Court is mindful that the respondents have sought to challenge the Surveyor-General’s diagram, possibly for non-compliance with section 29. The Court therefore states that no facts have been pleaded before this Court that leaves it to conclude that the dispute between the parties falls within the confines of section 29 of the Land Survey Act. There are certain jurisdictional facts required by section 29. The facts pleaded do not meet the requirements of section 29. Section 29 is activated when the owner or the Surveyor General requests an agreement regarding a dispute concerning a boundary or beacon. There is no evidence before the Court that either the owner or Surveyor general requested an agreement. Section 29 requires, if there has been such a request, that the matter be solved through an attempt to reach agreement. No evidence that there has been such an attempt. Section 29 then provides if no resolution is reached, then the Surveyor-General can refer the matter to arbitration. Again, there are no facts before the Court that the Surveyor-General has referred the matter to arbitration. It also appears that the section was to be applied between owners of properties as section 29(1) refers to an “agreement between the owners concerned”.

[34] It does not appear to the Court that section 29 of the Land Survey Act has been engaged in this case.

Point in limine 2: Non-joinder of the Surveyor-General

[35] The respondents contend that there has been a material non-joinder of the Surveyor-General. They rely on section 46 of the Land Surveys Act for this contention. The section provides that before any application is made to a court for an order affecting the performance of any act in a Surveyor-General’s office the applicant shall give notice to the Surveyor-General before the hearing. The Surveyor-General is then given an opportunity to provide the Court with a report.

[36] The relief being sought from this Court involves access to the property and an order for the demolition of structures. The Surveyor General is not mentioned in the relief. The Court has not provided with any basis to conclude that the relief sought affects the performance of the Surveyor-General. More directly, the section does not require the joinder of the Surveyor-General, only notice. In other words, even if the section were to apply, it demands notice, not joinder.

Point in limine 3: Stay of proceedings

[37] The respondents, during the hearing, mentioned it may be appropriate to stay the proceedings as the respondents are seeking to challenge the Surveyor-General’s diagram. The respondents did not request a stay. The respondents’ counsel referred to the fact that it may be appropriate to stay the proceedings. The respondents did not seek or launch a stay of proceedings. To date, no such application serves before the Court. The only reference before the court is a one-liner that the second respondent “intends to bring an application to have the Surveyor-General’s diagram cancelled”.

[38] The Court was concerned about conflicting decisions relating to the same dispute. If the Court in this case pronounces on issues which are being challenged in the another application it will cause confusion. To prevent conflicting decisions on the same dispute, the Court invited the parties to place information regarding the challenge to the Surveyor General's diagram before the Court.23 The Court received a short response from a candidate attorney at Eskom’s attorneys of record that indicated no stay would be sought, but received nothing at all from the respondents. Had there been such a challenge and the respondents wished for the matter to be stayed, the Court’s invitation would have been welcomed with open arms. However, the Court received no respondent from the respondents

[39] The Court can only consider the facts that serve before it and the relief being requested by the parties. Whilst the Court has a general discretion to order a stay, that discretion must be sparingly exercised.24 It cannot be appropriate for the Court to exercise such a discretion where it has not been presented with an application for stay nor has it, despite extending an invitation, been provided with a factual basis for the stay. The Court also weighs that there is a public interest element to this matter that mitigates a stay of proceedings and weighs in favour of a determination of the dispute.

Point in limine 4: Material dispute of fact

[40] The respondents contend that the parties disagree, factually, about the location of the servitude. The respondents contend that Eskom knew about this factual disagreement when it launched the proceedings. Eskom ought to have made used of trial proceedings and not motion proceedings.

[41] Eskom disagrees. Eskom believes that the issue relates to the interpretation of a Notarial Deed of Servitude and interpret the provisions that give rise to the servitude. To the extent that there exists any dispute of fact, Eskom contends that as the respondents have provided no positive evidence directly contradiction Eskom’s version, there is no bona fide dispute of fact.

[42] As the question the Court has been requested to address is the interpretation of the Notarial Deed of Servitude, that it an issue of interpretation, not one of fact. To the extent that there is a dispute of fact, it does not relate to the interpretation of the servitude. The parties agree about the entire factual substrata relating to the interpretation of the servitude.

Order

[43] In the result, the following order is granted:

a) The application is dismissed with costs.

____________________________

I de Vos

Acting Judge of the High Court

Delivered: This judgment is handed down electronically by uploading it to the electronic file of this matter on CaseLines. As a courtesy gesture, it will be sent to the parties/their legal representatives by email.

Counsel for the plaintiff: BONGANI MANENTSA

STHANDO KUNENE

Instructed by: Mamateal Attorneys

Counsel for the Respondent: S LUTHULI

Instructed by: TTS ATTORNEYS INC

Date of the hearing: 02 August 2022

Date of judgment: 20 October 2022

1 The option was in Afrikaans and no English version was provided to the Court.

2 The option provides -

8.6 Eskom mag met konstruksie begin sora Eskom die Aanbod soos in paragraaf 8.4 hierbo uitgeoefen het, vir die rede betaal Eskom rente soos in paragraaf 8.9 uiteengesit is.

8.10 Sou Eskom die Aanbod aanvar, sal dit die reg he om registrasie te verkry van die regte op enige manier waarvoor voorsiening gemaak is in die Registrasie van Akteswet 1937, en indien Eskom sou verkies om die regte te register in algemene terme sal alle verwysings na ‘n spesifield roete uitglaat work uit die notariele ooreenkoms. Nieteenstaande die voorafgaande sal sodandige uitlating op geen manier Eskom se kontraktuele verpligtinge om die lyn aan tle op die roete waaroor oorengekom is, raak nie. Eskom sal die reg he om daarna weer die registrasie van die servituut in algemene terme te wysig deur registrasie met verwysing na ‘n goegekeurde kaart. Die notariele ooreenkoms sal die voorwaarde vervat soos uitgeengesit in Aanhangsel A.

8.11 Die redelike koste van die registrasie van die notariele ooreenkoms en van enige daaropvolgende ooreenkoms wat die roete van die servituut omskryf deur verwysing na ‘n goedgekeurde kaart en die koste van sodanige kaart, sal deur Eskom betaal word.

3 The clause provides -

3.1 geen gebou of struktuur mag bo of onder the oppoervlakte van die grond binne 27.5 meter vanaf die hartlyn van enige kraglyn opgerig of aangebring word nie of binne 10.0 meter van enige struktuure onderstunigns meganisme.

4 Haviland Estate (Pty) Ltd & Antoehr v MacMaster 1969 (2) SA (A) at 322

5 Kruger v Joles Eiendomme (Pty) Ltd and Anather 2009 (3) SA (SCA) para 8

6 Kruger v Joles at para 8

7 Natal Joint Municipal Pension Fund v Endumeni Municipality 2012 (4) SA 593 (SCA)

8 CL 21-10 para 21

9 CL 21-10 para 22.

10 Natal Municipal Fund para 42

11 CL 2-10 para 23.

12 CL 21-11 para 25

13 CL 21-14 para 38

14 CL 21-14 para 39

15 The respondents used the land surveyor Mr Nichola Marambire. Who said that he is unable to conduct a survey of the servitude area and required the SG diagram from the Surveyor -General, see CL1.1-6.

16 CL 1.1-5 para 11

17 CL 1.1-11

18 CL 20-10 para 21

19 2012 (1) SA 58 (SCA), para 26. See also, M on behalf of L, a child v Member of the Executive Council for Health: Gauteng Provincial Government (A5015/2020) [2021] ZAGPJHC 501 (8 October 2021)

20 CL 191- 53

21 Kruger v Joles at para 8

22 Natal Joint Municipal Pension Fund v Endumeni Municipality 2012 (4) SA 593 (SCA)

23 On 31 August 2022 the Court through its Registrar invited the parties as follows -

"Dear Attorneys

Kindly note that the parties are requested to file a practice note before close of business Monday, 05 September 2022 addressing these two questions:

1.Is it common cause that the respondent is challenging the accuracy/lawfulness of the Surveyor General’s diagram (“the challenge”)?

2. If so, what prejudice would there be to any party, if the Court were to request that the papers in the challenge be placed before this Court in order for the Court to determine if this matter ought to be stayed pending the outcome of the challenge?

In the event that the parties agree on these two issues and there is no prejudice, the parties will be provided an additional opportunity to file written submissions dealing with the issue of a stay before close of business Friday, 9 September 2022."

24 Clipsal Australia (Pty) Ltd v Gap Distributors (Pty) Ltd 2009 3 All Sa 491 SCA 1.

1

Cited documents 1

Judgment 1

| 1. | Oasis Liquor Wholesalers CC v Doornfontein Girls College (Pty) Ltd t/a Destiny Girls College (28571/20) [2021] ZAGPJHC 501 (20 July 2021) | 1 citation |