REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA

IN THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA

GAUTENG DIVISION, PRETORIA

Case No: 46833/18

REPORTABLE: NO OF INTEREST TO OTHER JUDGES: NO JUDGE KUNY 26 JUNE 2023 YYYY..YYYY............. YYYYYYYY SIGNATURE DATE

In the matter between:

CORNELIUS MARTHINUS DU PLESSIS Applicant

and

HERMANUS ALBERTUS STRAUSS Respondent

JUDGMENT

KUNY J

The applicant instituted motion proceedings against the respondent on 3 July 2019 seeking the following order:

1 Declaring that the Agreement of Sale of Member’s Interest in the close corporation Alrette Rentals CC, registration number 2005/175827/23, concluded between the applicant and the respondent during May 2017, has been validly cancelled by the applicant.

2 Ordering the respondent to make payment to the applicant of a sum of R2 500 000 together with interest thereon at the rate of 10,25% per annum from 1 June 2019 to date of payment.

3 Cost of suit.

4 Alternative relief.

The respondent counter-applies for the following relief:

1. That the agreement entered into between the parties on 1 June 2017 (annexure “A” to the respondent’s answering affidavit) be rectified as follows:

1.1. Clause 7.3 thereof is deleted;

1.2. Clause 10.2 thereof is rectified by inserting, at the beginning of the clause, the following: “Save for certain income tax returns and annual financial statements that have not yet been submitted, ...”

1.3. The following further clause is inserted after clause 10.2 thereof:

“10.3 The CLOSE CORPORATION shall be obliged to take all reasonable steps to ensure that the outstanding income tax returns and annual financial statements referred to in 10.2 above are submitted to SARS, and the SELLER undertakes to assist the CLOSE CORPORATION therein”

2. The applicant is ordered to forthwith sign all documents and take all steps necessary for purposes of registering, in the records of CIPC, the applicant as the sole member of Alrette Rentals CC (registration no 2005/175827/23) (“the close corporation”);

3. The applicant is ordered to take all reasonable steps and sign all documents for purposes of procuring the release of the respondent from his suretyship obligations to BMW Financial Services (Pty) Ltd in respect of the close corporation’s obligations to it;

4. The applicant is ordered to pay the respondent’s costs of the counter application;

5. That such further and/or alternative relief be granted to the respondent as the court may deem fit.

The matter was set down for hearing on the ordinary opposed motion court roll on 12 May 2022. However, soon after argument commenced, it became clear that insufficient time had been allocated for the hearing of the matter. Accordingly, by agreement between the parties, the matter was postponed to permit a special allocation. Argument resumed on 23 August 2022.

The dispute between the parties concerns an agreement for the purchase and sale of the members’ interest in Alrette Rentals CC (“the close corporation”) entered into on 1 June 2017 (“the agreement”). In terms of the agreement the applicant purchased 100% of the respondent’s membership interest in the close corporation for an amount of R2.5 million.

The applicant alleges that he is entitled to an order confirming the cancellation of the agreement based on the respondent’s breach thereof on two grounds:

The failure of the respondent to deliver a tax clearance certificate in respect of the close corporation as provided for in clause 7.3 of the agreement.

A breach of the warranty in clause 10.2 of the agreement that the close corporation has and will have at the effective date complied with all the provisions of the Close Corporation Act and all laws relating to income tax or any other legislation which may affect the close corporation. It is alleged in this regard that the close corporation did not have an operating licence required in order to legally conduct businesses carried on by divisions of the close corporation, namely The Buzz and Avo Transfers.

In a letter of demand dated 25 April 2019 the applicant called upon the respondent in terms of clause 14.1 of the agreement to remedy the aforesaid breaches within 14 days of the notice, by the delivery of:

A tax compliance certificate confirming that as at the effective date of the agreement (ie. 1 June 2017) the close corporation had complied with all provisions of the Tax Act and Value Added Tax Act.

An operating licence issued in terms of the National Land Transport Act 5 of 2007 in favour of the close corporation in respect of four Toyota Quantum minibuses and two Toyota Avenza vehicles.

The respondent was advised that in the event of the respondent failing to comply with the demand, the applicant would cancel the agreement and tender return of his member’s interest in the close corporation to the respondent.1

On 20 May 2019, GJ Pienaar of attorneys Pienaar Kemp Inc (“Pienaar”) responded to the above letter in the following terms:

Difficulties arose with SARS in regard to obtaining a tax clearance certificate. The respondent (through his wife) was in the process of regularising the close corporation’s position. Pienaar requested that a reasonable period be given to obtain the tax clearance certificate.

At the time that the respondent conducted the shuttle business he did not apply for an operating licence. The business conducted by Buzz and Avo Transfers is not the main business of the close corporation. Vehicles belonging to the transfer businesses could be rented out whilst the issue pertaining to the tax clearance certificate and operating licences were being sorted out.

Should it not be possible to obtain operating licences because a tax clearance certificate had not been issued, the issue would have to stand over until the certificate was obtained. The applicant could rely on the indemnity provided in clause 17 of the agreement to claim any losses that may be suffered.

The reasons stated by the applicant were not valid grounds for cancelling the agreement and any attempt to do so would be regarded as a repudiation of the agreement.

In a letter dated 31 May 2019, addressed to Pienaar, the applicant notified the respondent as follows:

He elected to cancel the agreement with effect from 31 May 2019.

On the above date the applicant would hand the keys of the business to the manager, Jan Lotz, and remove all his personal possessions from the premises.

The applicant claimed repayment of the sum of R2.5 million against tender of the delivery of a signed amended founding statement CK2 in terms of which he resigned as a member of the close corporation.

The applicant claimed payment of an amount of R244 558 in respect of loans that he made to the close corporation from time to time. A separate letter of demand in respect of this claim would be sent.

CONCLUSION OF THE AGREEMENT FOR THE SALE OF MEMBERS INTEREST

The Business was defined in the agreement as the car rental business owned by Alrette Rentals CC trading under the name and style Avo Car Rentals inclusive of the shuttle business divisions respectively known as The Buzz and Avo Transfers.

In January 2017 the applicant took up employment with the close corporation to enable him to consider and investigate purchasing the member’s interest of the respondent in the close corporation. The applicant and respondent were personal friends. The respondent’s wife, Sarette Strauss, was the accounting officer of the close corporation.

The applicant at first expressed an intention to purchase a 50% member’s interest for R3 million. Pienaar was instructed to prepare a draft purchase and sale agreement. Included in the purchase was the member’s interest of the respondent in Duzack Property Investments CC. This entity owned the immovable property on which the close corporation traded.

The applicant contends that the first draft of the agreement (annexed to the applicant’s founding affidavit marked B2) was sent to the parties by Pienaar on 7 March 2017. However, it emerged from the papers that Annexure B was in fact the second draft of the agreement. To demonstrate this the respondent annexed a portion of a draft that did not contain the drafting note after clause 8.2 “Plus: Tax Clearance certificate and the new fleet facility.” The applicant accepts the respondent’s allegations that this was the first draft. Annexure B is accordingly referred to as the second draft.

After the second draft was produced, the applicant indicated that he would like to acquire 100% of the business. He proposed an initial payment of R2.5 million and the balance to be paid in instalments. It was also proposed that Duzack be excluded from the purchase and that the trading premises be leased by the close corporation until the applicant had sufficient cash resources to purchase the property. The applicant’s proposal in this regard is reflected in an email that he sent Pienaar on 7 April 2017 stating:

$ Ek COP wil die heIe besigheid Koop teen R 3,000 000.00. Maar gaan net as intrapslag R2,500 000.00 betaal en die balans af betaal. Moet net n skedule aanheg. Sal dit later stuur.

$ Dan huur COP die gebou teen n bedrag per maand tot ek reg is en vermoee het op die gebou te koop.

$ Ek dink ek lees dit raak in die kontrak dat die besigheid se belasting betaal is tot op datum, maar voeg net by dat Avo moet n TAX clearance certificate verskaf met ondertekening van die kontrak asseblief.

On 2 May 2017 Pienaar responded by email setting out his understanding of the terms of the new proposed agreement and calling for comment and instructions.3 It is common cause that certain further discussions ensued between the parties in terms of which the applicant reverted to the purchase of 50% of the close corporation for an amount of R2 million. The applicant’s revised proposals were communicated to Pienaar in the forms of comments in the body of Pienaar’s email of 2 May 2017.

Pienaar proceeded to produce the third draft (Annexure E to the founding affidavit), reflecting the purchase of a 50% members interest in the close corporation (excluding Duzack) for an amount of R2 million.4

It is common cause that after the third draft was produced the applicant and the respondent met to discuss and negotiate the terms of the final agreement. The applicant alleges that the parties made handwritten notes and amendments on the third draft and this was provided to Pienaar to enable him to produce the final agreement that was signed by the parties. The respondent denies that the draft with the handwritten notes was furnished to Pienaar and alleges that the notes and amendments on the third draft were “far removed” from the final version of the agreement that was ultimately signed. However, a comparison between the two versions shows that most of the handwritten marks on the third draft were in fact carried through to the final version.

On 9 May 2017 under cover of an email, Pienaar provided the final redrafted agreement to the parties. This was signed by them at Boksburg in each other’s presence, purportedly on 1 June 2017 (“the agreement”). It provided that the applicant purchased 100% of the respondent’s members interest in the close corporation for an amount of R2 500 000. The effective date of the sale was 1 June 2017.

The cover page of the agreement indicates that the parties to the agreement are respondent as the seller, the applicant as the purchaser and the close corporation. However, the parties are defined in the body of the agreement as “The SELLER and PURCHASER referred to collectively”.5 The respondent accepts that the agreement was not signed by the close corporation and did not argue that it was a party to the agreement.

DISPUTED CLAUSES IN THE AGREEMENT

The respondent alleges the following in his answering affidavit in regard to the agreement:

Pienaar was not aware at the time that he drafted the agreement that the close corporation’s tax clearance certificate was not available and could not be procured until SARS had corrected an “error in their system”.

Clause 7.3 read with clause 10.2 contained important factual inaccuracies, namely, as was known to the parties at the time the agreement was concluded, that the close corporation was not compliant with tax legislation and a tax clearance certificate could not be issued to the close corporation.

Pienaar included Clause 7.3 in the agreement as a result of a misunderstanding or lack of proper instructions. It is alleged that the inclusion of this clause was a “drafting error”.6

Pienaar was under the erroneous impression that the tax certificate contemplated in clause 7.3 was either already available or could easily be procured on short notice.7 Had Pienaar known that a tax clearance certificate could not be produced “on demand” he would not have included clause 7.3 in the agreement.

It was not the intention of the parties when they entered into the agreement that the respondent would personally be obliged to procure and deliver a tax clearance certificate to the respondent.

Clause 7.3 and 10.2 do not correctly reflect the true common intention between the parties and these clauses of the agreement stand to be rectified.

As regards the complaint that there was a breach of the warranty because the close corporation did not have an operating licence in respect of the transport of passengers, the respondent alleged as follows:

During January 2017, the applicant, as manager of the close corporation, completed an application for “accreditation” of the close corporation as a tourist transport operator. The respondent signed the application on behalf of the close corporation on 15 February 2017. The form required that an original tax clearance certificate be attached.

He (the respondent) should not have signed the above application because it was not necessary for the close corporation to obtain “accreditation” in respect of Avo Transfers. The reason given was that it did not transport passengers.

There were existing valid transport permits for the vehicles in the Buzz division. It is alleged in this regard that Bernadette de Klerk had already applied and paid for permits prior to her selling The Buzz to the close corporation. The Department of Transport had approved the permits in December 2016 and the applicant merely had to collect them.

Instead of collecting the permits, the applicant took it upon himself to lodge new applications for permits.

The Buzz, which transports passengers on a small scale, was compliant at the effective date.

At the time Mr Pienaar wrote his letter of 20 May 2019, he had not yet considered and researched the issues in relation to the requirements and existence of permits. These were only required and had in fact been obtained in respect of “the Buzz minibus”. To the extent that Pienaar’s letter concedes that such permits were required for the close corporation’s other business activities, such concession was incorrect as a matter of law.

RECTIFICATION

The grounds for rectification claimed by the respondent in respect of clause 7.3 were essentially that the inclusion of this clause was a drafting error caused by a misunderstanding or by Pienaar not having proper instructions.

It is clear from the applicant’s email to Pienaar dated 7 April 2017, that the applicant intended that a clause be inserted in the agreement relating to the provision of a tax clearance certificate. Clause 7.3 (as it appears in the final agreement) started out as a drafting note in the second draft. However, it appeared in its final form in the third draft, and it was a term of the final agreement.

On the facts that are not in dispute the inclusion of clause 7.3 was a unilateral error that arose either from the respondent not having furnished Pienaar with proper instructions in regard to the formulation of the terms of the agreement or from a misunderstanding on his part, or both.

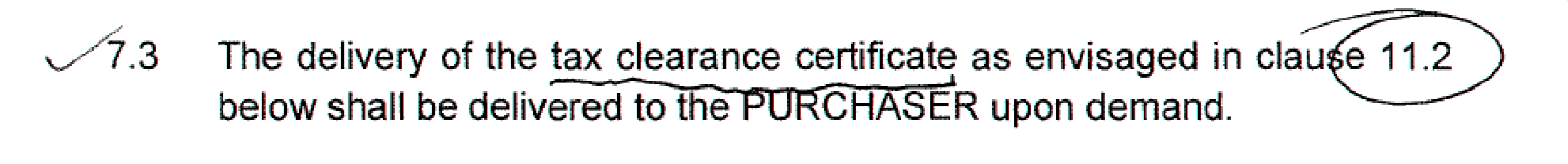

As appears from the third draft of the agreement, there were handwritten marks against clause 7.3 as follows: there was a tick in the margin against clause 7.3, “tax clearance certificate” was underlined and the clause 11.2 was circled. The markings appeared in the actual document as follows:

The applicant alleges in his replying affidavit (which also served as his answering affidavit to the counter application) that he and the respondent went through the third draft agreement together. He further alleges that the tick was made by him and the underlining and circle were made by the respondent.

The respondent, as applicant in the counter application, bears the onus to prove that the agreement does not reflect the common intention of the parties. The respondent did not dispute the allegations in relation to the above marks. On the basis of the principles set out Plascon‑Evans Paint Ltd v Van Riebeeck Paints (Pty) Ltd 1984 (3) SA 623 (A) these allegations must therefore be accepted. The marks prove that the respondent agreed to the inclusion of clause 7.3, was fully aware of its presence in the final agreement, and voluntarily assumed the obligation to provide a tax clearance certificate upon demand.

In National & Overseas Distributors Corporation (Pty) Ltd v Potato Board 1958 (2) SA 473 (A) at page 479G-H Schreiner JA held as follows:

Our law allows a party to set up his own mistake in certain circumstances in order to escape liability under a contract into which he has entered. But where the other party has not made any misrepresentation and has not appreciated at the time of acceptance that his offer was being accepted under a misapprehension, the scope for a defence of unilateral mistake is very narrow, if it exists at all. At least the mistake (error) would have to be reasonable (justus) and it would have to be pleaded.

In George v Fairmead (Pty) Ltd 1958 (2) SA 465 (A) at p471 the court said:

When can an error be said to be justus for the purpose of entitling a man to repudiate his apparent assent to a contractual term? As I read the decisions, our Courts, in applying the test, have taken into account the fact that there is another party involved and have considered his position. They have, in effect, said: Has the first party ‑ the one who is trying to resile ‑ been to blame in the sense that by his conduct he has led the other party, as a reasonable man, to believe that he was binding himself?

On 14 February 2017 the applicant sent an email to the respondent advising him that a new application for permits had to be made and that the tax clearance certificate was needed in this regard. On 10 April 2017 the applicant sent a further email to the respondent asking for the tax clearance certificate for the applications to the Department of Transport. It was known to the parties prior to settling and signing the agreement 2017 that the close corporation required the original tax clearance certificate in order to obtain a permit to transport passengers.

Both parties were cognisant of the fact that a tax clearance certificate would be required in order to obtain passenger transportation permits from the Department of Transport. The applicant made it clear at the time that the agreement was negotiated that he required a tax clearance certificate and there was nothing in his conduct that could have mislead the respondent or Pienaar in this regard.

Pienaar’s alleged lack of knowledge at the time he produced the various drafts of the agreement of the tax status of the close corporation does not assist the respondent. Had the respondent insisted on the deletion of clause 7.3 before the final agreement was signed, the applicant may well have withdrawn from the agreement. By agreeing to the insertion of clause 7.3 the respondent led the applicant to believe that the tax clearance certificate could be provided if it was called for. I cannot find that clause 7.3 was erroneously inserted in the agreement. However, even if there was an error, viewed objectively against the facts, such error could in any event not be said to be reasonable.

There has been debate in our law about the nature of a warranty. In Protea Property Holdings (Pty) Ltd v Boundary Financing Ltd (formerly known as International Bank of Southern Africa Ltd) and others 2008 (3) SA 33 (C) the court stated:

[36] ............. counsel for the first defendant referred to two types of warranties found in the law of insurance, namely affirmative and promissory: a warranty is affirmative if the party concerned warrants the truth of a representation regarding an existing fact, and promissory when the party concerned warrants the performance of a certain act or that a given state of affairs will exist in the future. Counsel sought to apply this distinction to contracts in general. Having done so, they argued that if the clause in question were to be interpreted as being an affirmative warranty of fact, it could never serve as the basis for a claim for specific performance because, to the knowledge of the plaintiff, the warranty was incorrect at the time when it was given ......... If, on the other hand, the clause were to be interpreted as a ‘promissory’ warranty, certain other problems would arise, with which I shall deal below. [footnotes omitted]

The court Protea Property Holdings (Pty) Ltd went on to point out that as a special term, the term ‘‘promissory’’ is a misnomer. It reasoned that all warranties are promissory in that they give rise to an obligation or promise to perform.8 The court concluded in paragraph 39:

[39] In the final analysis, there is no unanimity among the authorities as to what the expression ‘warranty’ connotes, save that it is a contractual term. It accordingly becomes necessary, as pointed out by Farlam JA in Masterspice (Pty) Ltd v Broszeit Investments CC, ‘in every case where the expression is used, to examine the terms of the contract in question closely in order to endeavour to ascertain in what sense the parties have used it’. [footnotes omitted]

The basis for the rectification to the wording of the warranty in clause 10.2 and the insertion of a new warranty as clause 10.3, is obscure. The respondent alleges that the close corporation was not tax compliant when the agreement was signed because of an error in the SARS’s e-filing system. The argument appears to be that because this was known to the parties, the warranty contained in clause 10.2 could not have been agreed to by them. This also appears to be the justification for rectifying the agreement by inserting a new term (as clause 10.3) that requires the close corporation to take all reasonable steps to ensure that the outstanding income tax returns and annual financial statements are submitted to SARS.

I can find no basis whatsoever for the rectification of clause 10 in the manner contended for by the respondent or in any other way. The proposed rectification is contrary to the undertaking given in clause 7.3. It would eviscerate the warranty in clause 10.2 given in relation to the compliance by the close corporation with tax legislation. By granting such relief the court would be rewriting the contract for the parties. No basis has been alleged on which it can or should do so.

It is understandable that the applicant would require the warranties as they stand in clause 10. The fact that the close corporation has not complied with the relevant legislation at the effective date or that the respondent, with hindsight, wished that he had contracted on a different footing, is not a basis for the rectification sought. In the circumstances, I come to the conclusion that the respondent’s claim for rectification must be dismissed.

CANCELLATION OF THE AGREEMENT

Clause 12.3 of the agreement provides:

12.3 If either party allows the other party any leniency, extension of time or indulgence the party so doing shall not be precluded from exercising its rights in terms of this Agreement in the event of any subsequent failure by any party to whom the indulgence, leniency or extension of time has been granted, nor shall the party so doing be deemed to have waived any of its rights to rely on a subsequent breach of this Agreement by the other party.

Clause 14.1 of the agreement provides:

14. BREACH

14.1 In the event of either the SELLER or the PURCHASER committing a breach of any term or condition of this contract and remaining in default notwithstanding 14 (fourteen) days written notice calling for the remedy of his breach, the aggrieved party shall be entitled without prejudice to such aggrieved party’s right to claim damages arising from such breach, either:

14.1.1 to claim an Order for specific performance; or

14.1.2 to cancel this contract.

In further resisting cancellation of the agreement the respondent contends that the applicant waived his right to cancel because of the time lapse between the date on which the agreement was concluded and the date of demand. Alternatively, it was contended that the applicant acquiesced in and is estopped from relying on the unavailability of the said certificate to cancel the agreement.

In North Vail Mineral Co Ltd v Lovasz 1961 (3) SA 604 (T) at p606 9 the court stated the following in regard to legges commissoriae:

Clause 9 is a lex commissoria (in the wide sense of a stipulation conferring a right to cancel upon a breach of the contract to which it is appended, whether it is a contract of sale or any other contract). It confers a right (viz. to cancel) upon the fulfilment of a condition. The investigation whether the right to cancel came into existence is purely an investigation whether the condition, as emerging from the language of the contract (a question of interpretation), has in fact been fulfilled (Rautenbach v Venner, 1928 T.P.D. 26)

The respondent admits that the close corporation was not compliant with the provisions of the law relating to income tax as at the effective date.10 Furthermore, it was not in dispute that, prior to the final letter of demand, a number of written requests had been made for the tax clearance certificate:

On 28 June 2017, M van der Merwe of VDM Rekenmeesters (the accounting officer of the close corporation at the time) sent an email on the applicant’s behalf to Ms Strauss, requesting the tax clearance certificates for all the tax numbers.

On 29 January 2018 the applicant sent an email to Ms Strauss advising her that he required the tax clearance certificate.

On 28 March 2019 the applicant sent an email to Ms Strauss asking her whether she had any feedback from SARS in relation to the tax clearance certificate for Avo and Alrette Rentals CC and whether he could obtain same.

In addition to the above, it is common cause that the applicant and respondent held a meeting on 25 May 2018 to discuss problems relating to the close corporation. The applicant alleges that at this meeting he told the respondent that the close corporation’s non‑compliance with its tax obligations and the failure to obtain a tax clearance certificate had become an increasingly serious problem. This allegation was not denied by the respondent.

Although the respondent alleged that there were valid permits in existence, when asked to produce the permits in terms of Rule 35(12), he was unable to do so. Instead the respondent produced documents that showed that in or about 2015 the previous proprietor of The Buzz, de Klerk, had made application for permits and had paid an application fee.

In response to the above allegations the applicant stated that in February 2017 he sent an employee of the close corporation to the Department of Roads and Transport to try and obtain the permits that De Klerk had applied for. It is alleged that the employee was advised by an official of the Department that the close corporation would have to submit a new application for permits, accompanied inter alia by a valid tax clearance certificate. The applicant’s allegations in this regard are supported by documentary evidence, including a letter from De Klerk authorising the employee concerned to collect the alleged permits.

The evidence shows on a balance of probabilities that the close corporation was not in possession of an operating licence or permit in terms of section 50(1)11 at least insofar as The Buzz was concerned. It is not disputed that permits were a legal requirement for the transport of passengers for reward. Accordingly, the warranty stating that the close corporation had complied with legislation that may have affected it, was breached. No rectification in respect of this aspect of the warranty was sought by the respondent.

In my view, the applicant has established that a proper demand was made upon the respondent to provide him with the tax clearance certificate envisaged in clause 7.3 as well as the operating licences issued in terms of the National Land Transport Act 5 of 2007 (ie. the permits). There is no evidence that the demand was complied with.

Furthermore, there is no evidence that the applicant waived his right to call for a tax clearance certificate. Insofar as the applicant may have given the respondent indulgences and extensions of time within which to provide the tax clearance certificate, the applicant is entitled to rely on clause 12.2. Accordingly, in my view, the lapse of time does not preclude the applicant from exercising his right to insist on the provision of such certificate in terms of clause 7.3, as he did in May 2019.

Clause 14.1 gave the applicant the right to cancel the agreement in circumstances where a breach is not remedied within 14 days. It is not necessary to prove that the breach was material or that it went to the root of the contract. I accordingly find that the applicant validly cancelled the agreement and is entitled to an order in terms of prayer 1 of his notice of motion.

RELIEF

The applicant claims payment of R2 500 000 together with interest thereon from the date of cancellation of the agreement (1 June 2019) to date of payment, at the rate of 10.25%. The applicant submits that this is the prescribed rate of interest at the date of cancellation.

The applicant contends, without reference to any authority, that it is a general principle that upon cancellation of an agreement the parties are required to make restitution of the performance received. The proposition is of a very general nature. There are other remedies available to an aggrieved party who cancels an agreement and various factors have to be considered in deciding upon appropriate relief.

The grant of an order restitutio in integrum (sought by the applicant) is said to be found on equitable considerations.12 Granting equitable relief requires that the relevant considerations justifying such relief be placed before the court.

Neither party addressed the court, either in their papers or in argument, on the basis for a fair, just and appropriate order. I am not satisfied that all the relevant issues in this regard have been canvassed on the papers, particularly having regard to following:

The full amount of the purchase price was not paid in cash. Part of the consideration was settled by way of the exchange of a Land Cruiser vehicle and an unidentified machine. The value of this property was not specified. It is not alleged whether this exchange was based on a contract of sale or barter. This may be relevant to the manner in which restitution should take place and to the payment of interest.

The breaches alleged by the applicant arose at the time that the agreement was signed. The delay of almost two years before the applicant exercised his right to cancel the agreement may have a bearing on the form of the relief that should be granted to the applicant.

The applicant’s claim for interest on the monies he paid in terms of the agreement forms a substantial component of his claim. Issues relating to the rate of interest and the date on which the payment of interest should commence to run were not canvassed on the papers or in argument.

In the circumstances I propose to postpone the determination of the relief sought in prayer 2 of the notice of motion to give the parties an opportunity to deal with this aspect before an order is made in this regard.

COSTS

The applicant at this stage has established that he is entitled to a declaratory order that the agreement has been lawfully cancelled. The respondent has been unsuccessful in his counter claim for rectification of the agreement.

In accordance with the usual rules the applicant, at the very least, is entitled to a portion of his costs pursuant to the grant of the relief sought in prayer 1 of the notice of motion. However, as the determination of the relief sought in prayer 2 of the notice of motion remains outstanding, in my view, it would be appropriate to reserve the question of costs.

There is a further issue that I wish to draw to the attention of the parties:

The applicant filed three sets of heads of argument, dated 11 May 2021 (57 pages), dated 21 September 2021 (72 pages) and concise heads of argument dated 24 June 2022 (33 pages). In total the heads of argument were 162 pages in length.

The respondent filed heads of argument drawn by J Both SC dated 10 April 2022 (34 pages) and concise heads of argument dated 14 July 2023 (28 pages). In total the respondent’s heads of argument were 62 pages.

After the first hearing in May 2022 I requested counsel to file concise heads of argument before the next hearing. The respondent’s concise heads were almost as long as the main heads of argument filed before the first hearing commenced. The applicant’s concise heads of argument were even longer.

I consider the applicant’s lengthy sets of heads to have been unduly prolix. I do not consider the respondent’s concise heads to be concise. Documents of this length often detract from the task of identifying and synthesising the relevant factual and legal issues. A party’s right to be heard does not afford counsel free reign to file voluminous heads of argument, and in some instances, multiple sets.

Counsel’s attention is drawn to Caterham Car Sales & Coachworks Ltd v Birkin Cars (Pty) Ltd and Another 1998 (3) SA 938 (SCA) at paragraphs 37 and 38 and to Ensign‑Bickford (SA) (Pty) Ltd v AECI Explosives & Chemicals Ltd 1999 (1) SA 70 (SCA) at 84H-85B-C.

I consider that the costs order in this matter should reflect the court’s disapproval with the prolixity referred to above. Counsel is invited to make submission to the court in this regard.

ORDER

In the circumstances I make the following order:

1 A declaration is granted that the Agreement of Sale of Member’s Interest in the close corporation Alrette Rentals CC, registration number 2005/175827/23, concluded between the applicant and the respondent on or about 1 June 2017, has been validly cancelled by the applicant.

2 The relief sought in prayer 2 of the applicant’s notice of motion is postponed sine die.

3 The applicant is granted leave to file a further affidavit in relation to the determination of the relief sought in paragraph 2 of the notice of motion and the respondent is afforded an opportunity file an answer thereto. No further affidavits may be filed save with the leave of the court.

4 The costs are reserved.

______________________________

JUDGE S KUNY

JUDGE OF THE HIGH COURT

GAUTENG LOCAL DIVISION, PRETORIA

Date of hearing: 12 May 2022 and 23 August 2022

Date of Judgment: 26 June 2023

Applicant’s counsel: NGD Maritz SC

Respondent’s counsel: E Kromhout

1Although the applicant purchased a 100% members interest, he only was only registered as a 50% member at the time the application was brought. The respondent retained a 50% member’s interest until such time as he was released from his suretyship in favour of BMW.

2Annexure “B” to the Founding Affidavit, Caselines AA44

3Annexure “D” to the Founding Affidavit.

4Annexure “E” to the Founding Affidavit, Caselines A61

5Caselines AA77

6Paragraph 48.3, Caselines A168

7Paragraph 56.4, Caselines A176

8Protea Property Holdings (Pty) Ltd, supra, paragraph 37

9Cited in Oatorian Properties (Pty) Ltd v Maroun 1973 (3) SA 779 (A) at 785

10See for example para 29, Caselines A147, para 30, Caselines A148, para 39, A153

11National Land Transport Act, No 5 of 2009

12Bonne Fortune Beleggings Ltd v Kalahari Salt Works (Pty) Ltd en Andere 1974 (1) SA 414 (NC), Feinstein v Niggli 1981 (2) SA 684 (A), Extel Industrial (Pty) Ltd v Crown Mills (Pty) Ltd 1999 (2) SA 719 (SCA), Prefix Properties (Pty) Ltd and Others v Golden Empire Trading 49 CC and Others 2011 (2) SA 334 (KZP)