60

IN THE REGIONAL DIVISION OF KWAZULU NATAL HELD AT THE REGIONAL COURT LADYSMITH CASE NUMBER SH 45/ 2020

In the matter between:

The State

Versus

Siphesihle Majola

Sibusiso Dladla

Nduduzo Xulu

Thulani Showick Mbhele

Sithembiso John Mbuyazi

Bongani Nxumalo

___________________________________________________________________

JUDGMENT

|

No. |

TOPIC |

PAGE NO. |

|

1. |

Introduction |

3. |

|

2. |

Google Maps |

3.-4 |

|

3. |

Mr. Mohammed Ismail |

4. |

|

4. |

Mrs. Fathima Ismail |

5. |

|

5. |

Mrs. Yesso Singh |

5.-6 |

|

6. |

Mr. Gerald Juggiah |

7. |

|

7. |

Mr. Thandanae Malinga |

7 |

|

8. |

Mr. Bongumusa Majola |

7 |

|

9. |

Mr. Robert Anton Everson |

7 -8 |

|

10. |

Mr. Bongani Xolani Zwane |

8 |

|

11. |

Exhibits |

8-9 |

|

12. |

Mr. Siphesihle Majola |

9-10 |

|

13. |

Mr. Sibusiso Dladla |

10-11 |

|

14. |

Mr. Nduduzo Xulu, and Mr. Makhosini Sphelele Xulu |

11- 12 |

|

15. |

Mr. Thulani Showick Mbhele |

12- 13 |

|

16. |

Mr. Sithembiso John Mbuyazi |

13 |

|

17. |

Mr. Bongani Nxumalo |

13-14 |

|

18. |

The concept reasonable doubt |

14-15 |

|

19. |

Credibility |

15- 17 |

|

20. |

Evaluation of state witnesses testimony |

18-22 |

|

21. |

The standard of reasonable suspicion |

23- 28 |

|

22. |

Cell Phone Evidence |

28-31 |

|

23. |

Evaluation of defence witnesses |

31- 40 |

|

24. |

Approach to bare denial defence |

41 |

|

25. |

Circumstantial Evidence |

41- 48 |

|

26. |

Common Purpose |

48 |

|

27. |

Finding |

50 -56 |

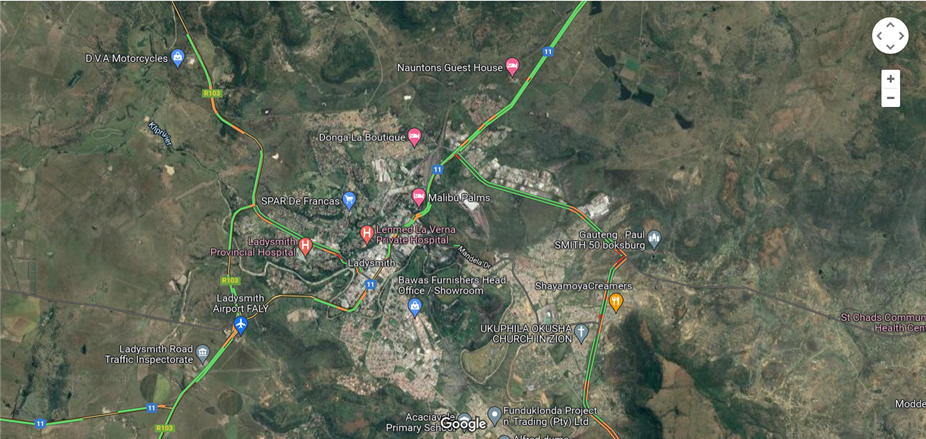

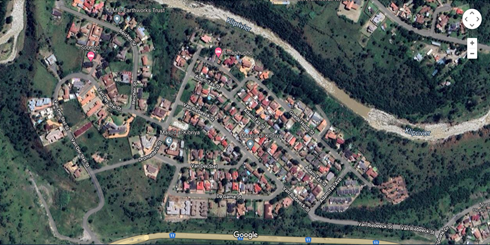

Humans experience the world through their senses and are exceptionally visual creatures. Outside stimuli are experienced and those experiences provide us with information and ideas. With that in mind, engaging the senses is critical, and one of the most important of those senses is vision. It is with an understanding of the preceding sentences to visualize the different routes the town of Ladysmith offers to enter and exit it. The Court adopts this methodology for the parties to understand the judgment. It is important to envisage the routes and more specifically the locations where it is alleged the perpetrators of the crimes of Robbery with aggravating circumstances as intended in terms of section 1 of the Criminal Procedure Act 51/ 1977 read with section 51 (2) of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 105 of 1997 were during the night of the 5th November 2019. Below are two digital images from

-

The routes entering or exiting the town of Ladysmith

-

The suburb of van Riebeeck Park

[1] At half-past eight at night on the 5th November 2019, Mr. Mohammed Ismail was traveling to his residence from the mosque. He resides at Van der Stel Street, van Riebeeck Park a suburb in the town of Ladysmith. He pressed the remote to open the main gate and thereafter the remote to open his garage. Before he could jump out of his vehicle he saw two men running into his garage. They came to the door and demanded money. Mr. Ismail testifies he was out of the vehicle. The two men took him into the house. One of the men pointed a firearm at him, demanding money. They pulled him into the lounge and hit him on his head with the firearm. They kept on demanding money.

[2] His wife came towards him. They were still demanding money. He took out an amount of six hundred (R600.00) Rand that was in his pocket. His wife came towards him. The alarm went off. They ran from the house. Mr. Ismail testified he went to see if there was no one else in the house. The alarm company arrived. The Police arrived after the alarm company. He did not see the direction his attackers ran. The persons who attacked him faces were not covered. He received treatment from paramedics who came to his house. He testified he is not able to identify or recognize any of the men who attacked him.

[3] Mrs. Fatima Ismail testified she was at her residence on the 5th of November 2019. At about 20h 30 pm she heard the gate open. She heard her husband screaming. She pressed the panic alarm. She was in the kitchen and ran to the lounge. She saw two men running out of the kitchen. It was two African men. The one person had dreadlocks the other was bigger than the other person. The one-man with the gun was wavering the gun asking where is the money, where the money. The one with the dreadlocks had a silver gun in his possession. The other person grabbed her and asked where is the money. They started to push her towards the dining room area. She saw her husband laying on the floor. There were two other men with her husband. The one man dragged her. There were four men on their property. The witness testified she was praying. The man said she must shut up. They said to her she must not scream.

[4] The witness testified she tried to press the alarm again. Her husband was kicked and hit on his head. He was tied whilst he was laying on the floor. They kept on asking where is the money? Her husband took money from his pocket and gave it to them. They wanted more money. He said he did not have more money. The witness testified she was dragged. The witness testified the men ran away from her property. She did not see the direction they took when they ran. The persons from the alarm company responded. Thereafter the Police arrived at the scene. The paramedics attended to her husband. They provided treatment for the injuries he sustained.

[5] Mrs. Yesso Singh testified she resides at Van Riebeeck Park in Ladysmith. She knows the Ismail family. They reside less than a kilometer from her residence. She testified on the 5th November 2019 at about quarter past eight (20h 15 pm) in the evening she got home. She drove into the yard and opened the main gate. Her children were with her. She observed three (3) guys running to the cul de sac into a bush next to her house. The witness testified she entered the house. She testified there are many lights around her house. The street lights and the lights in and outside of her house lit the whole area. The men who entered the cul de sac ran fast, but she was able to catch a glimpse of their clothing. She alerted the Community Police Forum group about the three suspicious black males who ran into a bush.

[6] She continued to watch them. She peeped through the door to see what they were doing. She observed one of the men had dreadlocks. A vehicle came down the road. The vehicle was parked in the cul de sac facing her door. The persons entered the vehicle and drove off. Mrs. Singh testified it was a white Isuzu single cab. She wrote the vehicle registration number on a piece of paper. The vehicle sped off briskly. The vehicle whilst it was stationary was about ten (10) meters away from her. She told her husband what happened. The Police were contacted whereupon she gave the piece of paper to a member of the South African Police.

[7] Mr. Gerald Juggiah testified under oath he is a member of the South African Police stationed at Ladysmith. On the 5th of November 2019, he was on duty. At about half-past ten (22H 30 pm) in the evening, he was with Sergeant Masengemi. He was posted as the van driver. They were asked to be on the lookout for a white Isuzu bakkie with GP registration plates. The witness testified he observed the vehicle on Newcastle Road exiting from town. He followed the vehicle for a short distance. At the BP garage, they stopped the vehicle. Two occupants were in the front of the vehicle. At the back of the vehicle were four (4) persons. It was African males and all of them were inside the vehicle. He instructed all of them to alight from the vehicle.

[8] He instructed them to lay on the ground , which they did. He focused on one individual who had dreadlocks. He wore a blue jacket and blue jeans. The witness testified he could not remember the type of shoes. His colleagues, Ngubane and Ngcobo were busy with some of the other occupants of the vehicle. Mr. Juggiah testified he search the person and found a nine (9) millimeter pistol in his hip. He asked the person if he had a licence to carry the firearm. He said he does not have a licence. The firearm was booked into the SAP 13 Register. The firearm was black and had a serial number. It contained seventeen (17) live rounds of ammunition. The serial number is FFSD 74909C. The witness testified whilst he was searching for the person he noticed his colleagues were doing the same. He testified he could not recall who was the driver of the vehicle.

[9] Mr. Thandanane Malinga testified under oath he is a member of the South African Police stationed at Ladysmith. He holds the rank of constable and has two (2) years of experience. On the 5th of November 2019, he was on duty. At about 21h 45 pm they received information about a robbery that took place at Van Riebeeck Park. He was in the presence of Constable Mpungose. They received a description of the vehicle. It was an ISUZU Light delivery van with a canopy with GP registration. They drove around Ladysmith to investigate to see whether they find a vehicle that fits the description. They found the vehicle that matches that description on Lyell Street. They followed the vehicle and called for backup. His colleague, Mr. Juggiah arrived as a backup.

[10] At Newcastle Road, they stopped the vehicle close to the BP garage. They ordered the occupants out of the vehicle. They searched the driver. He spoke to the first person who alighted from the vehicle. He searched the driver of the vehicle Nduduzo Victor Xulu. He was standing. He searched him and found a firearm on the right side of the jean he was wearing. It was a Taurus 9-millimeter handgun. He asked the accused for documents of the firearm. He said he does not have. He placed the firearm in a plastic bag. Two other firearms were recovered. He does not know from whom it was recovered. The accused were all placed in one van. He proceeded to the Police Station. Mr. Juggiah followed up with more information. They proceeded to the Ekuvukeni area. The firearm was handed into the SAP 13 / Register 1178/2019. The vehicle the accused used was seized.

[11] Mr. Bongumusa Mpungose testified under oath he is a member of the South African Police stationed at Ladysmith. On the 5th of November 2019, he was on duty. He was with Constable Malinga. At about 21h 45 pm they received information about a house robbery that took place in the Van Riebeeck area. They received information about the vehicle that might have been involved in the commission of the crime. The vehicle emerged from Short Street traveling into Lyell street. The witness testified they parked their vehicle on Lyell street.

[12] Mr. Masengemi testified he is member of the South African Police stationed at Ladysmith. On the 5th November 2019 he was on duty. He was in the presence of his colleagues when they followed a ISUZU Vehicle. The Vehicle was stopped close to the BP Garage. He did not search any of the accused. He retrieved several cell phones from the vehicle. He booked it into the SAP 13 Register.

[13] Mr. Robert Anton Everson testified under oath he is a member of the South African Police employed as a Senior Registry Clerk. He has nineteen (19) years of experience. He has been deployed at the National Task Team Communication Data Analysis since 2012. He has nine (9) years of experience as a data analyst. He has completed training in investigating and management of cyber and electronic crime, and notebook analysis and received training from various service providers to read, understand and interpret the information on billing reports. He has testified in court on many occasions to interpret data analysis. He received information from Sergeant Zwane the investigating officer in this case of data of electronic communication in PDF and Excel format. He received the information on the 25th of February 2021. He compiled two affidavits about several cell numbers.

[14] The witness testified he received the physical handsets and applied for information in terms of section 205 of the Criminal Procedure Act 51/ 1977 to analyze the information contained on the cell phones. He received the cell phone from Sergeant Zwane whereupon he placed it in a different bag with money. He does not recall the amount of money the original bag contained. It is his testimony the information on the cell phone cannot be changed. It can be copied, but it cannot be altered in any way. He testified about the various calls that were made from the cell phone numbers that he received. He testified about cell phone towers, how it operates and what affects communication between various cell phone calls. Mr. Everson complied with various charts of communication between various cell phones. The Court will later have discussed his testimony during the evaluation of the testimony and his findings.

[15] Mr. Bongani Xolani Zwane testified under oath he is a member of the South African Police stationed at Ladysmith. He has twelve (12) years of experience and is the investigating officer in the matter. He received cell phones and from them, he obtained cell phone records and he asked Mr. Everson to analyze them. The cell phone exhibits were booked into the SAP 13 Register. He opened the bags that contained several cell phones and an amount of money of Four hundred and sixty (R460.00) Rand. The exhibit bag contained several cell phones and placed them into a different bag and provided it to Mr. Everson. The accused items and valuables were recorded and booked into a Register.

[16] Throughout the trial, several documents were presented as part of the evidentiary material. These exhibits are:

-

Key to Photos and Photo Album at van der Stel Street, Ladysmith

-

Copy from SAP 13 Register

-

Copy from SAP 13 Register

-

Copy from SAP 13 Register

-

Affidavit of Mzamo Mondli Cele in terms of section 212 of the Criminal Procedure Act 51/ 1977

-

Copy from Bail proceedings in Case number 2017/ 2019

-

Affidavit of Siyanda George Mailindzi in terms of section 212 of the Criminal Procedure Act 51/ 1977

-

i.

-

Affidavit of Londeki Shezi in terms of section 212 of the Criminal Procedure Act 51/ 1977

-

Warning statement of Siphesihle Majola

-

Warning statement of Nduduzo Victor Xulu

-

Warning statement of Bongani Aaron Nxumalo

-

Affidavit of Nkosinomusa Brian Masengemi

-

Affidavit of Nkosinomusa Brian Masengemi

-

Warning statement of Siboniso Dladla

-

Warning statement of Thulani Shadrack Mbhele

-

Warning statement of Sithembiso John Mbuyisa

-

Affidavit of Robert Anton Everson

-

Call Data

SIPHESIHLE MAJOLA

[17]Mr. Majola testified under oath he resides at Verulam. He is a thirty-five (35) year old man who is single and unemployed. He does not know the second accused. He does not know accused number four (4) but knows accused number three (3). Accused number three (3) resides in the same area he resides. On the 5th of November 2019, he was with accused number three (3). They came to Ladysmith to fetch a tent. The third (3) accused was sent by his father to fetch a tent. Mr. Majola testified he knows the fifth accused. He is his brother from the same mother, but a different father. They live together. He knows accused number six (6) as they live in the same area. On the 5th of November 2019, they left Durban. He was called by the third accused to fetch the tent for the church. They were four occupants in the vehicle. It was himself and the third, fifth, and sixth accused respectively. the third accused was driving the vehicle.

[18] Mr. Majola testified at a garage they observed a Police Van. the Police van was parked on the side near the road. they passed the Police Van when they noticed it was following them. Their vehicle was stopped at a place that did not have a parking place. The Police Officer spoke to the driver of the vehicle. It stopped parallel to their vehicle facing the same direction. Other Police vehicles approached. They came out of the vehicle. They were told to lay on the ground. They were searched, whereupon their cell phones were taken. They were assaulted. They were informed certain persons were robbed and they were suspected including the vehicle. They took the vehicle they traveled in. He was seated in the back of the vehicle. They were taken to a place that look like a forest. It had houses. They were four (4) persons in one Police vehicle. All of them were assaulted by members of the South African Police. He does not know Thulani Mbhele. He did not see where they took the fourth accused. He was also assaulted.

MR. SIBUSISO DLADLA

[19] Mr. Dladla testified under oath he knows the fourth (4) accused. He does not know the other accused. On the 5th of November 2019, he was in Steadville, Ladysmith. He was at his girlfriend’s place. It was in the afternoon. He said it was time to go home, but he did not look at the time. There were no taxis available. He decided to go to the garage to hitchhike. He does not know Ladysmith well. A white ISUZU vehicle approached. He asked for a lift to Dundee. The person told him they are going in that direction. The person was in the process of inflating the tire. Two persons were sitting in the bin of the vehicle. He did not know the driver or any of the occupants of the vehicle. A Police vehicle appeared and followed their vehicle. They flashed lights indicating the vehicle he was in should stop. The ISUZU vehicle stopped. They were ordered to lay down. Whilst on the floor they were handcuffed. It is his testimony he was abused. He was forced to show where the fourth (40 accused resides.

[20] They got there. The gate was locked. The Police forced themselves into the residence. He could hear Mr. Mbhele screaming. They came out with him from the house and put him into a van. They were charged at the Police station. He had a cell phone with him and one hundred and fifty Rand.

MDUDUZI VICTOR XULU

[21] Mr. Xulu testified his father asked Bongani Nxumalo to accompany him. The first and fifth accused accompanied them. They intended to fetch a tent that his father bought at Matiwane. They started at Phoenix where they fetched a tire. They went passed some other places. They drink along the way. They took a journey around Pietermaritzburg. He used the Majola phone as it had free minutes. He used his phone trying to save airtime. He got the number of Thulani Mbhele and tried to communicate with him. He is not sure about his health condition. They entered the town of Ladysmith and stopped at a garage. They drove past the garage when they noticed a Police vehicle that followed their vehicle. They kept on getting lost on the road. At about seven in the evening, they came to a place that looked like a park.

He observed a vehicle that flicked lights. At the second set of robots, they were told to stop their vehicle. He did not pick up speed. He parked his vehicle and next to his vehicle the Police vehicle stopped. Three (3) vehicles surrounded their vehicle. The Police asked them to alight from the vehicle. Mr. Xulu testified he was with Majozi seated in the front seat. Majola and Nxumalo were seated in the back. The Police made them lay down. They kicked them and asked them what did they want. They informed them they came from Durban and they offered a lift to one gentleman. They were taken to a bushy area where they were assaulted. There were two Police vans. they were taken to the Police station. He did not have cash with him. he was using a card. They were later in the presence of the second and fourth accused.

[22] Mr. Makhosini Sphelele Xulu testified under oath he resides at Inanda near Verulam. He resides there with his wife and children. He has been using the bakkie and he sends the children to fetch a marquee tent from Mr. Ngubane. He knows the gentleman from Inanda, but he resides at Matiwane. The witness testified he does not know accused number one, but he knows the fourth accused. He knows the fourth accused from church services. The fourth accused was of great assistance to Mr. Xulu to fetch the tent. It is his testimony the third accused did not have direction as to from where he must fetch the tent. Mr. Xulu testified Mr. Nhubane did not respond when he phoned him. He testified he asked Bongani Nxumalo to accompany his son. He knows the fifth accused from Inanda.

THULANI SHOWICK MBHELE

[23] Mr. Mbhele testified under oath he is employed at the Department of Health as a paramedic. He resides at Driefontein. He was at his residence, resting in an area called Schoeman. His highest level of education is grade twelve (12) and he has been working as a paramedic for fifteen (15) years. He knows the second accused and before his arrest, he knows the third accused. He does not know the fifth (5) accused. He was arrested where he rent at Uitvaal. The day before he was arrested he was in town. He bought some parts to fix his vehicle. The day before he went to a different place, Steadville. He was sleeping in the early hours of the morning. He was asked for directions to Matiwane area. He was phoned. He also phoned him to give him directions. He cannot remember at what time was the phone call. He was concerned that they might get lost.

[24] He returned a call to Mr. Xulu. He had two cell phones He recalls the MTN number that is 0835034630. He saw members of the South African Police arriving at his residence. He saw them in the yard. The Police Officers kicked and requested him to open the door. He was questioned if he knows Sibusiso Dladla. His response was they are friends. Mr. Mbhele testified he was assaulted by members of the South African Police. He was taken to a vehicle where he saw his friend, Sibusiso Dladla. The Police vehicle was parked on the road. He was able to recognize his friend. Mr. Mbhele testified he was taken to the Ladysmith Police Station.

Mr. Philani Mbhele testified under oath he resides at Uitvaal. He occupies a one-room RDP structure, two structures away from the fourth accused. He resides with his Lungile and the other room is occupied by Mr. Thulani Mbhele. The accused is a paramedic. He testified in the early hours of the morning he observed members of the South African Police at his premises. It is Mr. Mbhele's testimony the dogs were barking whilst he was asleep. Their barking woke him. He thought it was drunkards that were close to his residence. He observed Police men. He saw the fourth accused inside his house. The Police ask him about a person he is familiar with. He said no.

SITHEMBISO JOHN MBUYAZI

[25] Mr. Mbuyazi testified under oath he was arrested on the 5th of November 2019 at Ladysmith. He was a passenger in an ISUZU vehicle traveling from Verulam toward Matiwane. The third accused approached him and asked him to accompany him to fetch a tent. The third accused arrived early in the morning. Mr. Mbuyazi testified he is not familiar with the area. It was his first time in Ladysmith. He was seated at the front next to the driver. The third accused was the driver of the vehicle. There were five (5) of them in the vehicle. Four (4) of them left Durban traveling towards Matiwane. The second accused approached them seeking a lift at a garage. Mr. Mbuyazi testified they entered the garage when the second accused approached them. He got into the bin of the vehicle.

[26] Nduduzo said there was a vehicle that tried to stop their vehicle. The driver of their vehicle stopped the vehicle. Two (2) female officers approached their vehicle. They pointed firearms at them instructing them to lay on the ground. They complied. The Police treated them harshly. Mr. Xulu was brought by others to lay on the ground. He noticed Nduduzo was laying on the ground. The Police search them, but they did not find anything. They were assaulted by members of the South African Police. He saw the fourth accused the next morning at the Police Cells. He was in the presence of the second accused. He does not know the fourth (4) accused.

BONGANI NXUMALO

[27] Mr. Nxumalo testified under oath he was asked by the father of the third accused to go and collect a tent at Matiwane. He testified it was a mistake to arrest him as he did not know of a firearm or robbery. He testified he was in the presence of the first, third and fifth accused when they left Ethekwini. He was a passenger in the vehicle, whilst the driver of the vehicle was the third accused. He was seated at the back of the vehicle. He had money and his cell phone in his possession when they left Ethekwini. Whilst traveling he was playing games on his cell phone. He cannot recall if he made any outgoing calls. Accused two and four were arrested later. The second accused traveled with them from a garage in Ladysmith. He does not recall the name of the garage. He is not familiar with the area of Ladysmith.

[28] It was in the afternoon when they were arrested in Ladysmith. Their vehicle was stopped after they crossed two sets of robot intersections. They were not speeding. Mr. Nxumalo testified they were stopped by the Police and instructed them to alight from the vehicle. The five (5) of them were ordered to lay on the ground. They were assaulted by members of the South African Police. He told the Police he does not have anything with him except his cell phone. The Police Officer did not ask for permission to search them. He was forced to lay on the ground. The Police had firearms pointed at them when they told them to lay on the ground. He was kicked and there were two female Police Officers at the scene. The four of them who were traveling from Durban were taken to the Police station.

[29] It is not correct for a Court to reason that a reasonable doubt, to justify the acquittal of the accused, must be such a doubt as would influence you in your daily affairs, in carrying on business, or something of that sort. What is required for conviction is a moral certainty of guilt, and anything short of that necessitates an acquittal, whereas in daily affairs, and business, persons habitually act upon a balance of probabilities, and something much less than moral certainty, and it is rudimentary that a Court cannot convict because it thinks that the accused is probably guilty. It is to be remembered that it is improper to assess the evidence of defence witnesses against State witnesses, determine who appears more believable, and render judgment on that basis. A criminal trial is, in all cases, a determination of whether the State has proven the essential elements of the offences beyond a reasonable doubt. If there is reasonable doubt, the accused is entitled to an acquittal. Reasonable doubt is not based upon sympathy or prejudice; rather, it is based on reason and common sense. It is logically connected to the evidence or absence of evidence. It does not involve proof to an absolute certainty; indeed, such proof is rarely available. It is not proof beyond any doubt, nor is it an imaginary or frivolous doubt. However, more is required than proof that the accused is probably guilty. If the case is based wholly or chiefly upon circumstantial evidence, and that evidence is consistent with any rational conclusion other than that of the accused's guilt, the State has not satisfied the burden which is upon it. The onus is always on the State to prove, beyond a reasonable doubt, the crime for which an accused has been charged. The State must prove each element of the offence to that evidentiary standard.

CREDIBILITY

[30] The term “credibility” tends to be used to describe the honesty of the witness, or the witness’s readiness to offer truthful testimony. The Court has to decide whether a particular witness is telling the truth and determine the appropriate weight to place on the evidence If there is an indication that the witness is tarnished, or the testimony of a witness is inconsistent, the Court will reduce the weight which it assigns to his or her evidence. Similarly, if a witness is particularly motivated to help one side, demonstrates credibility challenges by offering inconsistent or inherently unlikely testimony, or is unable to respond to appropriate questions during cross-examination, the Court will reduce the weight that it assigns to his or her evidence.

[31] When it comes to assessing credibility in trials before me and correctly charging myself on the law, the following principles direct this Court’s analysis and assessment of the testimony of witnesses. This is particularly how this Court approaches the evidence in a case such as a case at bar:

-

The Court consider carefully all of their testimony;

-

It charts it.

[32] The Court, therefore, has a means of comparing what one witness has said against what another witness has said on each point of evidence the Court is aware that the issue of credibility is one of fact and cannot be determined by following a set of rules. The Court is careful to instruct itself that as the Court it must consider not only the witness' desire to be truthful but also opportunities of knowledge, powers of observation, capacity for recall, capacity to articulate, and the power or lack of power of memory of each witness. The Court, therefore, look to each witness and assess their testimony within the following factors:

-

the capacity of the witness to remember, the accuracy of the witness' statement,

-

the care of the witness in answering,

-

the sincerity of the witness in terms of the manner

-

the frankness of the witness in attitude and response to questions.

[33] Those foregoing points are guidelines for this Court to analyze the testimony. In addition to that, the Court considers as well as part of its assessment of each witness several factors in considering the examination and cross-examination of the witness.

-

Were there inconsistencies in the witness’ evidence at trial, or between what the witness stated at trial and what they said on other occasions, whether under oath or not? Inconsistencies on minor matters of detail are normal and generally do not affect the credibility of the witness, but where the inconsistency involves a material matter about which an honest witness is unlikely to be mistaken, the inconsistency can demonstrate carelessness with the truth-.

-

Was there a logical flow to the evidence?

-

Were there inconsistencies between the witness' testimony and the documentary evidence? -

-

Were there inconsistencies between the witness’ evidence and that of other credible witnesses?

-

Is there other independent evidence that confirms or contradicts the witness' testimony?

-

Did the witness have an interest in the outcome, or were they personally connected to either party? –

-

Did the witness have a motive to deceive?

-

Did the witness have the opportunity and ability to observe the factual matters about which they testified?

-

Did they have sufficient power of recollection to provide the court with an accurate account?

-

Were there any external suggestions made at any time that may have altered the witness’ memory?

-

. Did the evidence appear to be inherently improbable and implausible? In this regard, the question to consider is whether the testimony is in harmony with “the preponderance of the probabilities which a practical and informed person would readily recognize as reasonable in that place and those conditions?”

-

Was the evidence provided candidly and straightforwardly, or was the witness evasive, strategic, hesitant, or biased? –

-

Where appropriate, was the witness capable of making concessions not favorable to their position, or were they self-serving?

[34] Breaking down the body of evidence into its parts is a useful aid to a proper understanding and evaluation of iti. The Court says this because it is trite law there is no substitute for a detailed and critical examination of each and every component in a body of evidence. The credibility of an interested witness, particularly in cases of conflict of evidence, cannot be gauged solely by the test of whether the personal demeanor of the particular witness carried conviction of the truth. The test must reasonably subject his story to an examination of its consistency with the probabilities that surround the currently existing conditions. In short, the real test of the truth of the story of a witness in such a case must be its harmony with the preponderance of the probabilities which a practical and informed person would readily recognize as reasonable in that place and those conditions. Only thus can a Court satisfactorily appraise the testimony of quick-minded, experienced, and confident witnesses, and of those shrewd people adept in the half-lie and of long and successful experience in combining skillful exaggeration with partial suppression of the truth. Again a witness may testify what he sincerely believes to be true, but he may be quite honestly mistaken.

[35] In discussing the testimony of the first two state witnesses Mr. and Mrs. Ismail It cannot be forgotten that a robbery can be a terrifyingly traumatic event for the victim and witnesses. Not every witness can have the fictional James Bond's cool and unflinching ability to act and observe in the face of flying bullets and flashing knives. Even Bond might have difficulty accurately describing his would-be assassin. He certainly might earnestly desire his attacker's conviction and be biased in that direction. The complainant’s testimony was they were frightened and were not able to identify any of the assailants. The description provided of some of the assailants is generic in nature. The Court says this because Mrs. Ismail described the one assailant as bigger in build and the other had dreadlocks as a hairstyle. Such description does not take the matter further in so far as the identification of the accused is concerned. The concept of reliability recognizes that even an honest witness can be mistaken. Testimony may be “unreliable” because the witness had a poor opportunity to observe the factor about which he or she is testifying, and, therefore, could be mistaken. A few examples illustrate reliability concerns: (i) a witness may not understand what they observed or may not remember accurately what was observed. Ultimately, the less reliable the evidence, the less weight the Court will give it.

[36] Finding the testimony of the first two state witnesses unreliable in so far as identification is concerned does not mean their testimony does not carry any weight. Testimonial evidence can raise veracity and accuracy concerns. The former relates to the witness’s sincerity, that is, his or her willingness to speak the truth as the witness believes it to be. The latter concerns relate to the actual accuracy of the witness’s testimony. The accuracy of a witness’s testimony involves consideration of the witness’s ability to accurately observe, recall and recount the events in issue. When one is concerned with a witness’s veracity, one speaks of the witness’s credibility. When one is concerned with the accuracy of a witness’s testimony, one speaks of the reliability of that testimony. A witness whose evidence on a point is not credible cannot give reliable evidence on that point. The evidence of a credible, that is, honest witness, may, however, still be unreliable. In this case, the reliability of their evidence was attacked on cross-examination.

[37] The Court does however find the first two state witnesses to be credible witnesses in so far as the robbery is concerned. They were consistent throughout their testimony. There was a logical flow to the testimony and the first two state witnesses corroborated each other about the sequence of events. They were constant throughout the testimony that there were a few men who entered their residence. They confirm each other testimony that some of the men had firearms in their possession. These facts were not challenged during cross-examination. It was not disputed by the defence that the complainant was robbed and that he sustained injuries due to an assault upon him. What is the importance of their testimony is the following undisputed facts that were presented individually and collectively:

-

One of the assailants had in his possession a silver smallish gun

-

The complainant, Mr. Ismail was robbed of an amount of almost six hundred (R600.00) Rand that consisted of mostly ten (10) and twenty (20) Rand notes

-

The incident occurred at half-past eight (20h 30 pm) in the evening. Mr. Ismail's testimony about the time was understandable as it was based on the fact he returned from the mosque

-

The incident occurred at van der Stel Street in the suburb of van Riebeeck Park.

-

Men ran away from their residence when the alarm was activated

[38] Mrs. Singh was an excellent witness. Her testimony was rich in detail and context. She was challenged in cross-examination, but was firm in her response and answered all questions without hesitation. She was straightforward. She was focused and her attention to detail was notable. She was respectful in giving her answers to the legal representative of the accused and was responsive and not argumentative. Her attention was drawn to three (3) men because they ran towards a bush close to her residence. At that time, she was not aware of a robbery that took place at the Ismail residence. At all times she peeped through her door in observing what the men were doing. Mrs. Singh did not exaggerate her testimony. On the contrary, she was honest about her observations that she saw a glimpse of their clothing. She conceded the street lights were not functioning, but at her residence, there are various lights that she and her family installed to provide proper lighting. She described that one of the men had dreadlocks.

[39] Mr. Mthembu in his head of arguments reasoned common sense must be applied and that it is impossible that a witness would have been able to see a front number late at night while the headlights of the vehicle were shining straight in her direction. The Court with respect begs to differ. Her testimony was she observed the vehicle by lifting the blinds of the window. Her testimony even though it was challenged as she was observing the vehicle that was not far from her fence. It was not suggested to her during cross-examination that the light of the ISUZU vehicle shone to the extent that it made it impossible to her to observe the registration number of the vehicle. The legal representative of the second, fourth and fifth accused argued the witness changed her version that she was in a different room when she observed the vehicle. Mrs. Singh the representative of the state holds the view the observational conditions were good so much so that the witness was able to take down the registration of the ISUZU vehicle. The testimony of Mrs. Singh on this issue is unequivocal and has a ring of truth. She changed her position, because of the ISUZU vehicle that arrived. She closed the door she was peeping through and observed the persons from a window. The Court in its opening remarks of this judgment referred to the human senses of all human beings. The images of Google Maps depict the observational conditions of Mrs. Singh. -https://maps.app.goo.gl/Vsjy8srTZdoTDjxs7

[40] She observed the men and the ISUZU vehicle for almost ten (10) minutes. Her view was unobstructed. It was her testimony she moved her position from the door to the window because the ISUZU vehicle parked in front of her house. What is significant is her testimony she wrote the registration of the vehicle on a piece of paper and alerted her Crime Watch Group of the men in their area. She gave the piece of paper to a member of the South African Police. Regrettably, the piece of paper that formed an integral part of the eventual arrest of the accused was not adduced as evidence before this Court. It is however not fatal to the state’s case. In so far as the network of facts is concerned the following facts are important in so far as the testimony of Mrs. Singh is concerned-

-

The timeline of the events

-

The location where she observed the men

-

The identification of the ISUZU vehicle

-

The amount of time the vehicle was stationary in front of her location.

[41] A fair amount of criticism was rendered against the testimony of the Police officers who arrested the accused on the N 11 Road. The criticism varies from the statements made; to their observation at the scene, to the number of persons that were arrested. Perhaps it is prudent to pause at this stage and discussed our Courtsii approach to contradictions and or inconsistencies between witness testimony.

-

In considering the nature, number, and impact of contradictions it must always be remembered that witnesses do not always make a blow-by-blow mental recording of an incident. In many instances, witnesses do not even realize that they would be called upon to testify and be subjected to cross-examination about an incident. It is important when assessing the impact of a contradiction to weigh it up against the other evidence tendered in the particular case. Contradictions should not be evaluated without placing them in their proper context.

-

An all or nothing approach, i.e. two or more state or defence witnesses contradicted each other therefore the state’s case or the defence’s case should be rejected or they corroborate each other therefore their evidence must be accepted, and should not be adopted. One witness should not be crucified for the sins of another. It goes without saying that two witnesses may see the same incident differently for different reasons, for example, their power of observation, retention concentration, and narration.

-

When two or more witnesses contradict each other it might be that the one witness did not pay proper attention to the incident or because he/she cannot remember exactly what happened whereas the other witness observed and recalls everything. Proper attention must be given to the reasons or probable reasons for the contradictions. An all-or-nothing approach like a compartmentalized approach is flawed, unhelpful, and inimical to the holistic approach that ought to be followed.

-

Human experience tells us that memories are not perfect. Human experience tells us as well, for example, that two individuals may observe an event, and while there may be many similarities, there may also be some differences in the recollections. This is often expected. However, when the contradictions and inconsistencies are so significant and go to the heart of the elements of the offence, it causes the Court concern in assessing the credibility and reliability of a witness's evidence. Inconsistencies may emerge in a witness’ testimony at trial, or between their trial testimony and statements are previously given. Inconsistencies may also emerge from things said differently at different times, or from omitting to refer to certain events at one time while referring to them on other occasions. Inconsistencies vary in their nature and importance. Some are minor, others are not. Some concern material issues, and other peripheral subjects. Where an inconsistency involves something material about which an honest witness is unlikely to be mistaken, the inconsistency may demonstrate carelessness with the truth about which the Court should be concerned.

[42] Mr. Mthimkulu who represents the first (1), third (3), and sixth (6) accused reasons the members of the South African Police had no permission or consent to search the accused. He substantiates his argument based upon the statement of Mr. Juggiah reads ‘I informed them together with my colleagues that I am going to search them.” Mr. Mthembu who represents the second (2); fourth (4) and fifth (5) accused reasons there was a breach of the constitutional rights in so far as the search and seizure of firearms are concerned. He argued in his head of argument that consent was not provided to the members of the South African Police. It is his belief there was no compliance with sections 20 and 22 of the Criminal Procedure Act 51/ 1977. The State represented by Mrs. Singh holds the view that the search of the accused was lawful.

[43] In so far as the second to sixth counts are concerned the state relies upon section 22 of the Criminal Procedure Act 51/ 1977iii for the search and seizure of the weapons. To seize items without a warrant, the state is required to comply with section 20iv of the Criminal Procedure Act 51/ 1977. Individuals in South Africa have the right to walk the streets free from state interference. While the police must investigate crime, they have no generalized power to detain individuals who are going about their business, to investigate whether they may have been involved in criminal activity. The State argues that the Police Officers had a reasonable basis to detain the accused when they stopped him at the BP Garage. In particular, the State points to the following ground as the basis for their reasonable suspicion that the accused were involved in the robbery of the Ismail family at Van Riebeeck Park. The state avers the vehicle they traveled in is the same vehicle that was observed by one of the previous state witnesses at Van Riebeeck Park.

It is a truism that not all searches and/or seizures will violate section 14 of the Constitution. Only unreasonable searches and/or seizures will violate the Constitution. This, of course, means that the Court must balance competing interests and objectives. Hence, the right to privacy is qualified as are all rights guaranteed under the Constitution. What does the term “privacy” mean in modern society and law? It connotes liberty. It means the right to be left alone by the state; the right to be free from unjustified intrusion or interference; the right of the individual to determine for himself or herself when, how, and to what extent he or she will release personal information about himself or herself.

[44] To determine whether the conduct of the Police Officials falls within the ambit of section 20 of the Criminal Procedure Act 51/ 1977 it is firstly incumbent upon the Court to understand the meaning of the terms reasonable grounds and reasonable suspicion. A ‘reasonable suspicion’ is something more than a ‘mere suspicion’ and something less than ‘reasonable and probable grounds. It requires both a subjective and objective assessment. It is equivalent to ‘articulable cause’ and must be based on a constellation of objectively discernable facts. A ‘hunch’ based on intuition gained by experience will not suffice. In deciding the issue of ‘reasonable suspicion’ the court is required to view the facts and circumstances as a whole rather than in isolation.

[45] The "reasonable suspicion" standard is not a new juridical standard called into existence for this case. "Suspicion" is an expectation that the targeted individual is possibly engaged in some criminal activity. Reasonable suspicion means something more than a mere suspicion and something less than a belief based upon reasonable and probable grounds. Reasonable suspicion must be supported by factual elements which can be adduced into evidence and which permit an independent judicial assessment. Indeed, evidentiary requirements for meeting the reasonable suspicion standard are lower than that of reasonable and probable grounds. The distinction between "reasonable suspicion" and "reasonable and probable grounds" is merely the degree of probability that a person is involved in criminal activity.

[46] There are three levels of probability in determining whether the conduct of the Police Officials falls within the ambit of sections 20 and s 22 (b) of the Criminal Procedure Act. These levels are:

I. Mere suspicion: - “an expectation that the targeted individual is possibly engaged in some criminal activity. The “expectation” referred to is a tentative belief without clear ground for that expectation.

II. Reasonable suspicion- “something more than a mere suspicion and something less than a belief based on reasonable and probable grounds. Reasonable suspicion must be supported by factual elements which can be adduced into evidence and which permit an independent judicial assessment”; and

III. Reasonable and probable grounds: a belief which is based on credibly-based probability the standard “is one of reasonable probability. The distinction between ‘reasonable suspicion’ and ‘reasonable and probable grounds is merely the degree of probability that a person is involved in criminal activity.

[47] The suspicion must be supported by objective, articulable facts before it can be elevated beyond mere suspicion to reasonable suspicion. The suspicion must be reasonablev. The task of the Court is to consider all the evidence to be able to conclude whether the suspicion was reasonably held. The threshold for finding a reasonable suspicion is not high. The court must be able to find from the evidence that a rational connection” existed between the observed facts and the concluded fact whether subsequently proven or not. Reasonable suspicion must be supported by factual elements which can be adduced into evidence and which permit an independent judicial assessment. What must be remembered is that a "reasonable person, standing in the shoes of a police officer" does not mean a police officer who holds a pessimistic and overly negative view of the panoply of behaviors that humans engage in on a day-to-day basis. It cannot mean an officer whose observations of everyday actions are made through such a jaded lens that otherwise benign activity is precipitously characterized as criminal. Objectively ascertainable facts must exist to support a search and seizure. What must be measured are the facts as understood by the peace officer when the belief was formed. A hunch based on intuition or "feelings" gained by experience or a well-educated guess does not constitute reasonable suspicion.

[48] The arguments presented by both legal representatives are flawed in respect. The state’s case in so far as the search and seizure are concerned are not based upon consent but rather on the term whether the Police Officers had reasonable grounds to believe an offence has been or is suspected an offence has been committed. Recently the Supreme Court of Appealvi held inadmissible hearsay evidence can form the basis of reasonable suspicion by a peace officer. Our legal system sets great store by the liberty of an individual and, therefore, discretion must be exercised after considering all the prevailing circumstances.

[49] In deciding whether there was compliance with sections 20 and 22 of the Criminal Procedure Act 51/ 1977 the Court based its decision upon the following observations from the jurisprudence:

-

an arresting officer must subjectively hold reasonable grounds to arrest and those grounds must be justifiable from an objective point of view - in other words, a reasonable person placed in the position of the arresting officer must be able to conclude there were indeed reasonable grounds for the arrest

-

an arresting officer is not required to establish the commission of an indictable offence on a balance of probabilities before making the arrest, but an arresting officer must act on something more than a “reasonable suspicion” or a hunch

-

an arresting officer must consider all incriminating and exonerating information that the circumstances reasonably permit, but may disregard information that the officer has reason to believe may be unreliable

-

The court must view the evidence available to an arresting officer cumulatively, not in a piecemeal fashion

-

the standard must be interpreted contextually, having regard to the circumstances in their entirety, including the timing involved, the events leading up to the arrest both immediate and over time, and the dynamics at play in the arrest, and, the context includes the experience and training of the arresting officer

[50] In reviewing the totality of the circumstances of the arrest and search and seizure of the accused the Court the knowledge of the Police Officers affecting the arrest was sufficient to pass the test of reasonable grounds. They acquired the degree of probability necessary for reasonable grounds to arrest. At the time they formed their belief it was based on information about an ISUZU vehicle that was used as an instrument to get away from a crime scene. This belief was based upon objective articulate reasons provided by the complainants, but more specifically Mrs. Singh. The crimes were allegedly committed at night. The suspected perpetrators were traveling in a vehicle with the information they had firearms in their possession. The arrest was not based upon a hunch but upon information of a member of the public who alerted the Police. The search and seizure if the Court finds there was the seizure of firearms was lawful.

[51] Mr. Mthembu was critical of the testimony of Mr. Juggiah that he was not able to observe what his colleagues were doing at the time the arrests of the accused were affected. He reasons the testimony of Mr. Mpungose is inconsistent in so far as the number of persons that were asked to lay on the ground. He reasons the testimony of Mr. Mpungose is contradictory in so far as the number of members of the South African Police who entered the residence of the fourth accused. In his head of argument, he focused upon the testimony of Mr. Masengemi. He argued his testimony is contradictory to the information he received, the amount of money recovered and the Police Officials driving to Uitvaal intended to arrest the fourth accused. Mr. Mthimkulu was critical of the testimony of Mr. Malinga as he was uncertain whether the accused were standing or laying down when they were searched. He reasons the testimony of Mr. Masengemi is confusing as to who took them to Uitvaal and the purpose of it.

[52] Mrs. Singh holds an opposing view. She reasons at all times six accused were in the vehicle. She reasons some members of the South African Police observed them from Lyell Street until they were arrested. She said the witnesses recovered three (3) different firearms from the accused. Mr. Juggiah found a firearm with the sixth accused. Mr. Mpungose search and seized a firearm from the first accused. Mr. Malinga found a firearm and ammunition from the third (3) accused after he was searched. She said Mr. Masengemi's testimony was he covered his colleagues whilst the accused were searched. The firearms were shown to him.

[53] The criticism rendered against the testimony of Mr.Juggiah is unfounded. His testimony was consistent, straightforward, and unwavering despite vigorous cross-examination. It is indeed so his testimony is contradictory about whether consent was granted to search the sixth accused. The Court is not obliged to accept everything a witness says or conversely if the Court feels it cannot accept part of what a witness says, it is equally not obliged to reject the whole of that witness' testimony. The Court may accept the whole, none, or part of a witness's evidence. The Court has however dealt with it earlier during the judgment. Mr. Juggiah's testimony that it was a tense environment at the time the arrest was effected must be taken into account during the assessment of the testimony. He was firm in his stance about the clothing of the sixth accused and his hair was dreadlocks.

[54] Mr. Mthembu is spot on there are contradictions between the testimony of some members of the South African Police testimony. Mr. Malinga's testimony was the accused faced them when they were searched whilst Mr. Juggiah's testimony varies about the position of the accused. What must however be remembered is that the witnesses' testimony were they focused upon the accused they searched. There is no rule that where a witness has lied in his testimony must be rejected without more ado, all that can be said is that a witness whose evidence is deliberately false on one point is liable to be regarded with suspicion and distrust, and the Courtvii may conclude that his evidence on another point can be accepted

[55] It is trite law different witnesses see the same incident from different vantage points and slightly different points in time. They may have different opportunities for observation. Again discrepancies may arise quite innocently because witnesses have differing powers of observation. Their impressions may be colored by different emotional states such as fear and their powers of recollection and powers of descriptions may differ. the fact that there are discrepancies between the accounts of one witness and another does not in itself show that either of them is untruthful or unreliable or that the case of the party calling them is built upon an uncertain foundation. Notwithstanding the slight differences, the Police witnesses corroborated each other on most of the material aspects.

[56] A significant aspect of the State’s evidence related to cell phone calls that the state submits is strong circumstantial evidence that supports the finding that the accused communicated with one another on November 5, 2019, to coordinate the execution of their plan to rob the Ismail residence. To rely upon the evidence, the State has to prove the cell numbers and devices belong to the accused. From the evidence adduced in its totality the Court reach such a conclusion based upon the following:

-

The warning statements of the accused that documents their cell numbers as

|

EXHIBIT |

NAME OF ACCUSED |

CELL NUMBER |

|

Exhibit J |

Siphesihle Majola |

0608018230 |

|

Exhibit K |

Nduduzo Victor Xulu |

0652683814 |

|

Exhibit L |

Bongani Aaron Nxumalo |

0640640953 |

|

Exhibit O |

Sibusiso Dladla |

0721051635 |

|

Exhibit P |

Thulani Shadwick Mbhele |

0835034630 |

|

Exhibit Q |

Sithembiso John Mbuyazi |

0791020714 |

[57] The defence through the legal representatives of the accused did not oppose the application to tender the warning statements as evidentiary material before the Court. Mrs. Singh tendered the bail proceedings of the accused as part of the evidentiary material before the Court in terms of section 235viii of the Criminal Procedure Act 51/ 1977. Exhibit S the affidavit of Mr. Robert Anton Everson, his viva voce evidence, and the actual handsets provided sufficient proof the averments by the State about the identity of the cell phones have been proven as alleged. The testimony of the accused provided credence to the allegations by the state. These facts individually and collectively are sufficient proof that the accused are the owners of the cell phone as averred by the representative of the state.

[58] A propagation map is but a colorful manifestation of the prediction made by the software as to the area of a tower's coverage. It is not representative of the actual coverage area for any one cell phone call or message made or received at a particular time because it is not deterministic; it is, simply, a depiction of the general area within which a cell phone would be expected to connect to a specific tower. Cell phone propagation maps do not establish precise locations from which calls have been made, only the general area from which the call originated.

There is no evidence that the police duped the accused into furnishing their cell phone number and the Court is not prepared to draw this inference based on speculation. An accused is entitled, no doubt, to refuse to give the police such basic information as his name and addressix. In certain circumstances, even such basic information could incriminate an accused. It does not follow, in this Court’s view, that even before requesting an accused for even such basic information, the police must, in every instance warn an accused that such information might be incriminating. Every case has to be determined on its facts.

[59] Mr. Everson gave evidence regarding the general location from which several cell phone calls probably originated shortly before the murder. Specifically, the evidence related to several cell phone calls that were made before and after the robbery. . While these records did not pinpoint the location from which the calls were made, the States position was that they did show that a cell phone associated with the accused was in a specific geographic area that included the location of the robbery. . could not pinpoint the exact location from which the cellular telephone calls of interest were made, but rather he could merely indicate the general area from which the calls were likely placed, an area which included the scene of the shooting. The State relied on this as one piece of circumstantial evidence, among others, that supported the States’s case and the evidence of the States witness testified that when cellular telephones are turned on, they are constantly searching for the strongest signal. The strongest signal is usually the cell site closest to the cell phone and facing the cell phone directly. If there is an obstruction, that will cause the cell phone to search for another signal. Cell sites are located throughout the town and provide cellular signals which are picked up by the cell phone when a call is made or received. As already noted, the cellular phone generally searches for and uses the strongest signal available.

[60] The State relies on the cell phone evidence depicted in the association link chart between the accused entered through the state witness Mr. Everson, to support the argument that the accused were communicating with each other. A GPS map depicting the Van Riebeeck Park, and Hospital Park suburbs of Ladysmith; there is one cell site shown on this map. Chart B 2 is an association link chart between the accused on the 5th of November 2019. It includes the date, time of call, duration and cell tower registering on the cell site activated at the beginning of each call The States argument is that the cell phone records, as represented in Chart B 2 – The Association Link Chart between the accused demonstrate that the six accused communicated with each other on the day and night in question. . This argument is supported by a review of the records which shows clusters” of phone calls. The Association Link Chart between the accused B 1 attests to it. More about this later during the evaluation of the accused testimony.

[61] Mrs. Singh criticized the testimony of the first accused on the basis there is extensive communication between the first and fourth accused. She said even though the first accused testified he gave his phone to the third accused it cannot be accepted. She based her reasoning upon the fact there was communication with the accused three at 15:20:46, the time when it is alleged that they were still traveling and had not reached Ladysmith. There are several concerns about the testimony of the first accused. At a very late stage during this trial it came to the Court’s attention they were consuming alcohol in the back of the vehicle. He purposefully did not answer the question of whether there was a window between the bin of the vehicle where he was seated and the driver of the vehicle. Mr. Majola knew he would have to answer why he phoned the third accused whilst they were traveling in the ISUZU Vehicle.

[62] Mr. Majola's version was he was tipsy whilst traveling. It is surprising as it was never put to any of the state witnesses. Exhibit R depicts the ISUZU vehicle. The windows are tinted and the version presented by the accused was he was seated against the back window of the vehicle. Startingly despite being tipsy, the position where he was seated his attention was alerted to a Police Vehicle. From his testimony adduced and the testimony of the other witnesses, there is nothing untoward that occurred that would have alerted the first accused of the presence of the Police vehicle. It begs the question of why the first accused focused on the Police vehicle. Mrs. Singh the representative of the state bombarded the first accused about several calls that were made. He was unable to provide plausible explanations for the calls made.

[63] It is of vital importance to remember it is the version of the first, third, fifth, and sixth accused that at all times they were in each other’s presence, except for stages when alcohol was bought en route from Durban to Ladysmith. On the occasions, the accused were not in the vehicle they were close to each other. The picture painted by Mr. Everson tells however a different story. The Google map depicted on page three of this judgment depicts the R103 Road from Durban to Ladysmith. It is the only route a traveler can enter the town of Ladysmith from Durban from the testimony presented by the accused. It is the undisputed testimony throughout the trial that the third (3) accused was the driver of the vehicle. It begs the question why would the first accused phone the third accused twice? When confronted with the reasoning the accused did not provide an answer.

[64] The Association Link Chart between the accused show incoming calls to Mr. Majola's phone registering at 2G Military Park cell tower at 21: 17; 21: 19 and 22:15 from a cell phone of the fourth accused Mr. Thulani Mhele. is the cell site most proximate to the Subway restaurant between 22:27:38 and 22:29:52. It must be remembered The base station tower closest to the crime scene is Military Park which is 751meters apart. When considered together, these phone records show a pattern of corresponding cell site use between the first and fourth accused phones on the night of November 5, 2019. There is evidence that there is a general rule that a given call or SMS message will “register” or be “processed” at the cell site and sector with the strongest signal and that the signal is usually strongest when it is geographically closest to the phone handset. However, many factors can affect which site is used to process the call or SMS - the existence of any of these factors can create an exception to this general rule. For example, there are instances where, due to the topography of an area, the existence of obstructions, and the amount of cell phone “traffic” on the cell site, the cell site which is geographically closest to the phone may not be activated and, instead, the call or SMS may be processed through a less proximate cell site or sector. Much reliance is placed by Mr. Mthembu in so far as the above paragraph is concerned.

[65] It is this Court’s respectful view if there were only one or two instances of corresponding cell sites between accused one and four phones this would be insufficient evidence to draw the inference of the location of the cell phones. The same concern would result if there were significant time gaps between the various calls. However, here there are several instances where the cell phones, usually within minutes, but at most within 1 hour. There is an additional occurrence where two different but very nearby cell sites are registered. Throughout the trial, the defence adopted a strategy to show the fourth accused did not know the accused except for accused number two (2) and to a lesser extent, the third (3) accused. As will be shown during the evaluation of the testimony of the third (3) accused later the communication according to the defence version was to provide direction for the third accused traveling to Ladysmith and more specifically Matiwane. It has been established through the cell phone records a call was registered on the 5th November 2019 at 13: 21 43 between the first accused and the fourth accused. The importance of the information of the call lies in the following facts:

-

The parties from their version presented did not know each other;

-

The location of the call shows the tower was Ladysmith industrial.

[66] What is of significance is the time 21: 19 – 22: 01. Several calls were made between the parties where the cell phone tower closest was the Military Park cell tower. It begs several questions:

-

Why would several calls be made at that time?

-

From the Google Map presented the accused could not have been close to the tower based on their testimony presented about the route they took.

The totality of this evidence, combined, is sufficient to draw the rational and irresistible conclusion that the parties were communicating with each other during the night in question.

[67] Mr. Dladla was questioned about his reason for visiting Ladysmith. It was his testimony he came to Ladysmith to visit his girlfriend who was sick. When he arrived at the garage it was dark. He did not leave Tsakane. Mr. Dladla was not prepared to commit himself to any answers in so far as time and the driver of the vehicle are concerned. He was questioned about the Police Vehicle but did not answer direct questions posed to him. He could not answer any questions that draw his attention to the Police vehicle. He tried to justify why he made specific reference to the fact he referred to the fourth and fifth accused that was at the vehicle at the time of their arrest. His answer was spontaneous and he responded twice about the presence of the fourth accused. Mr. Dladla realized he made a mistake. His response when the question about it was he made a mistake. He testified that he was the fifth person. His testimony is not compatible with the position they were seated in the bin of the vehicle. Mr. Dladla testified he was seated closest to the door. Someone else in the bin of the vehicle reported to them the Police vehicle was following them. The Court finds it strange from how they were seated in the bin of the vehicle how he did not observe the Police vehicle.

[68] His testimony about being questioned about the fourth (4) accused does not make sense. It must be asked how would the Police know about his knowledge of the fourth (4) when the fourth accused was not in the vehicle? He was asked the very same question and his response was he thought the Police were looking for firearms. It is strange as the Court was under the impression the Police were looking for Thulani Mbhele. He provided long-winded answers to direct questions that required a simple yes or no answer. He was questioned about Exhibit T the cell numbers and calls that were made. His response was he does not dispute it. He conceded there was communication with the fourth accused. He could not explain why he was at three (3) different places in Ladysmith on the 4th of November 2019.

[69] From the onset of the cross-examination of Mr. Xulu, the third (3) accused had difficulty explaining variances between his testimony and the testimony of the first accused. The inconsistencies in their testimony arise from the arrangements or lack of arrangements that were made to travel to Matiwane. Mrs. Singh challenged the third accused testimony about his arrangements with the first accused the day before which the first accused denied. Mr. Majola's testimony was he only became aware of the traveling towards Ladysmith on the day in question. Mr. Xulu testified when he asked the first accused to accompany him he was under the influence of liquor. The testimony of Mr. Majola does not show that he was under the influence of liquor when asked to accompany the third accused. Mr. Xulu's use of the word reminds the first accused seems to suggest the first accused was aware of the travel to Ladysmith. His testimony as indicated supra shows otherwise.

[70] It is the undisputed testimony throughout this trial that the third accused was the driver of the ISUZU vehicle. No testimony shows otherwise. Closer scrutiny of the Google Map on the second page of the judgment shows that the third accused was driving on the N3 road entering Ladysmith from Durban. He continued on the N3 Road until he reached the Caltex Garage. The Court arrives at such a conclusion based upon the testimony of Mr. Xulu. He testified ‘We entered the town of Ladysmith whereupon we stopped at a garage’. His testimony is that he continued on that road until he was directed to stop by members of the South African Police. His testimony is in direct contrast to the Association Link Chart between the accused B 2.

[71] It shows the following:

The following incoming calls to the cell number 0652683814 from cell number 0827416385. Exhibit K and the viva voce evidence show that the cell number in the preceding sentence is the cell number of the third accused.:

|

Date |

Time |

Cell Tower |

Duration of call |

|

5th November 2019 |

20: 39:25 |

Rosemanor MTN |

22 |

|

5th November 2019 |

20:41:39 |

Military Park KZN |

25 |

|

5th November 2019 |

20:43:10 |

Military Park KZN |

12 |

|

5th November 2019 |

21:13:56 |

Military Park KZN |

41 |

|

5th November 2019 |

21:15:26 |

Military Park KZN |

19 |

|

5th November 2019 |

21: 23 :28 |

Observation Hill KZN |

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

[72] The State could not prove from the evidence adduced who had the cell phone that used the phone number 0827416385. What the state did prove that it belongs to one of the accused. The Court reaches such a conclusion for the following reasons:

-

Exhibit E was booked into the SAP 13 with number 1177. It consists of a Land Rover Cell Phone a Blue Nokia Cell phone, a black and white Alcatel Cell Phone, an LG cell phone, and two Black Samsung Cell phones.

-

The undisputed testimony of Mr. Nhosenomusa Brian Masengemi is that he found the cell phones in the ISUZU vehicle with an amount of Four hundred and sixty (R460.00) Rand.

-

The Mobile Phone Photo Album depicts Mobile exhibit 3 as a Nokia TA – 1010 mobile phone with IME 357678102793678. It is depicted in Photo 3.

-

The importance of cell number 0827416385 lies in the fact there was communication between the cell number and accused number one, three, and accused six.

-

The testimony of the accused is that accused two and four know each other and accused number three (3) had contact with the fourth accused. It is the undisputed testimony of the accused that accused number one, five, and six do not know the fourth accused.

-

Upon the analysis and the communication records, it was established the RICA information was Shaun Waring Jones

-

The testimony adduced during the trial is that the fourth (4) accused knew the second accused and he had telephonic contact with the third accused. The testimony of all the accused throughout the trial is that four of the accused were traveling from Durban to Ladysmith. The second accused does not know any of the accused except for the fourth accused.

[73] From all these facts adduced during the trial, it can be deduced it is the fourth accused is the person who had the device with cell number 0827416385.

[74] The suburb of van Riebeeck Park is on the left side of the N11 Road entering Ladysmith. From the testimony adduced by the third accused, he was not in that area on the day in question. What is surprising to this Court is how the third accused knew the direction to Dundee. It must be remembered it was the first time traveling to Ladysmith and more specifically Matiwane. There is no testimony adduced the second and fourth accused had any verbal communication about the route and direction to Dundee, especially at night.

[75] The testimony of the second and fourth accused is in direct contrast to each other. Mr. Thulani Mbhele disputes the statement by the second accused he visited him for traditional medicine at Uitvaal. Mrs. Singh confronted the fourth accused about a cell phone call between the fourth and second accused on the 5th November 2019 at 13: 37 31. The Association Link Chart between the second and fourth accused documents they were at the cell towers, Ladysmith Industrial, and the Ladysmith Swimming Pool at the time of the call. It is his testimony he did not speak to Mr. Dladla on the day in question. The Link Chart documents that fifteen (15) minutes earlier there was communication between the fourth accused and Siphesihle Majola. It must be remembered both parties testify they did not know each other. The undisputed testimony of Mr. Everson is that Mobile Terminated Call ( MTC) refers to a call within a telephone network in which the destination terminal is a mobile phone. The opposite term is called the Mobile Originated Call (MOC) in laymen's terms it means MTC Is the destination or receiving call whilst MOC Is the original caller. It is therefore surprising that Mr. Mbhele does not remember he made a call phone call to Mr. Dladla. What is more surprising is the Association Link Chart between the accused documents Mr. Mbhele called Mr. Majola the first accused. At the fear of repetition, it is important to stress Mr. Mbhele testified he was not in Ladysmith during the evening. The Association Link Chart between the accused Chart B 2. Paints a different picture: It documents

|

Date |

Time |

Cell Tower |

Duration of Call |

|

5th November 2019 |

21: 17:05 |

Military Park KZN |

40 |

|

5th November 2019 |

21: 19:47 |

Military Park KZN |

51 |

|

5th November 2019 |

21:21:30 |

Ladysmith Swimming Pool |

12 |

|

5th November 2019 |

21:55:20 |

Ladysmith MW |

50 |

|

5th November 2019 |

22: 01:25 |

Military Park KZN |

3 |

|

5th November 2019 |

22:07:33 |

Observation Hill KZN |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

[76] The communication took place between Mr. Mbhele and the first accused, Mr. Siphesihle Majola with cell numbers 0727495701 and 0712698874. During the period referred to in the above diagram, Mr. Mbhele did make any calls to Mr. Majola on a different cell number wit 0648895751. What the number, 0648895751 documents on the Association Link Chart is that at 22:34: 42 a call was received whilst the closest cell tower was at Ladysmith Industrial.