THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEAL

OF SOUTH AFRICA

Case number : 516/03

Reportable

In the matter between :

J Z BRINK APPELLANT

and

HUMPHRIES & JEWELL (PTY) LIMITED RESPONDENT

CORAM : MPATI AP, FARLAM, NAVSA, CLOETE JJA, JAFTA AJA

HEARD : 9 NOVEMBER 2004

DELIVERED : 30 NOVEMBER 2004

Summary: Defence of iustus error upheld where a personal suretyship by the signatory was included in an application for credit signed on behalf of a company. Order in para [13].

_________________________________________________________

JUDGMENT

(Dissenting pp 16-27)

_____________________________________________________

CLOETE JA/

CLOETE JA:

[1] A number of reported cases have dealt with problems which arise when a credit application form has embodied a personal suretyship by the individual who signed the form on behalf of the applicant. That is what happened in the present matter. The respondent, as the plaintiff, sued the company to whom it had granted credit (Guzto Log Homes (Pty) Limited) as the first defendant, and the appellant, who had signed the form on behalf of the company, as the second defendant qua surety. The respondent relied on the caveat subscriptor rule which is of course that a person who signs a document is taken to have assented to what appears above his signature.1 The appellant pleaded justifiable mistake (iustus error). The trial court (Motata J) gave judgment in favour of the respondent and refused leave to appeal. The appeal is accordingly with the leave of this court.

[2] The applicable principles of law are well established and require little discussion. The basis of the caveat subscriptor rule relied upon by the respondent is the doctrine of quasi-mutual assent. The locus classicus on the point is the following passage in George v Fairmead (Pty) Limited2:

‘When can an errorbe said to be iustusfor the purpose of entitling a man to repudiate his apparent assent to a contractual term? As I read the decisions, our Courts, in applying the test, have taken into account the fact that there is another party involved and have considered his position. They have, in effect, said: Has the first party ─ the one who is trying to resile ─ been to blame in the sense that by his conduct he has led the other party, as a reasonable man, to believe that he was binding himself? … If his mistake is due to a misrepresentation, whether innocent or fraudulent, by the other party, then, of course, it is the second party who is to blame and the first party is not bound.’

As the latter part of the passage just quoted makes clear, an innocent misrepresentation by the other party suffices3: The law recognises that it would be unconscionable for a person to enforce the terms of a document where he misled the signatory, whether intentionally or not. Where such a misrepresentation is material, the signatory can4 rescind the contract because of the misrepresentation, provided he can show that he would not have entered into the contract if he had known the truth. Where the misrepresentation results in a fundamental mistake, the ‘contract’ is void ab initio5. In this way the law gives effect to the sound principle that a person, in signing a document, is taken to be bound by the ordinary

meaning and effect of the words which appear over his/her signature, while at the same time protecting such a person if he/she is under a justifiable misapprehension, caused by the other party who requires such signature,6 as to the effect of the document.

[3] In deciding whether a misrepresentation was made, all the relevant circumstances must be taken into account and each case will depend on its own facts. For present purposes, all that need be said in this regard is that the furnishing of a document misleading in its terms can, without more, constitute such a misrepresentation7.

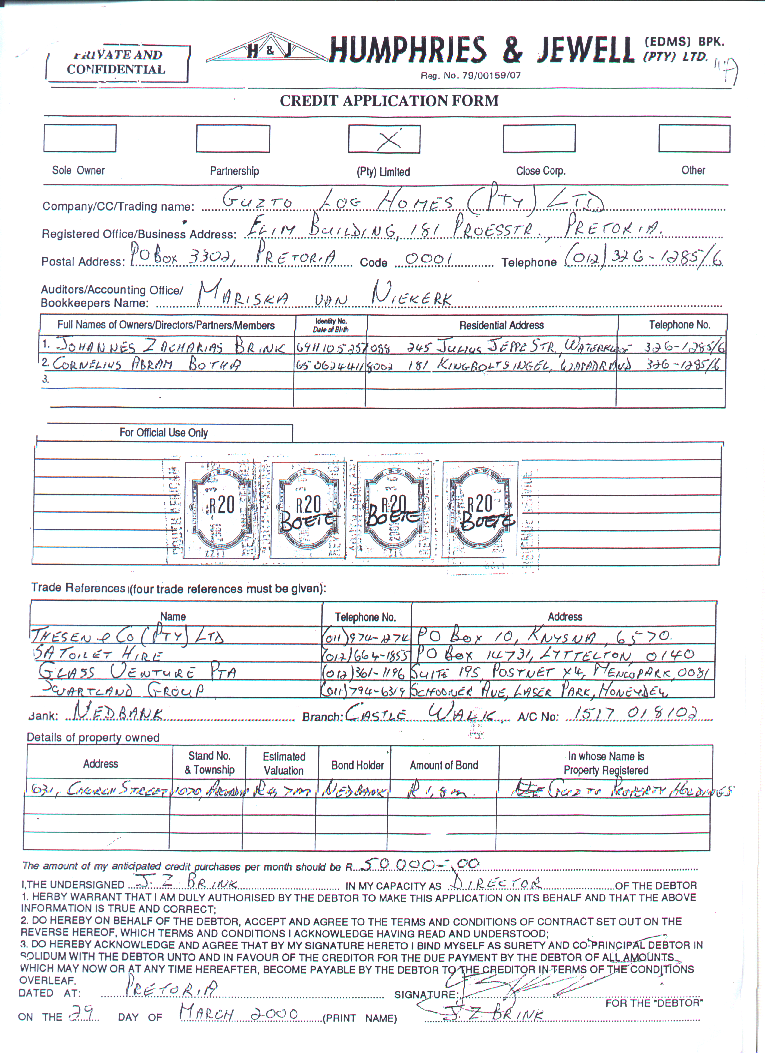

[4] The form signed by the appellant in the present matter is a one-page document. It is desirable to reproduce the front side of the form and not merely to describe it. A copy is accordingly appended to this judgment. The suretyship obligation is to be found in clause 3 at the bottom of the page. The reverse of the form has seventeen clauses headed ‘TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF SALE’ and a section for the respondent’s credit department to complete.

[5] The company of which the appellant was a director had a loose

arrangement with the respondent whereby, although it was a cash customer, it would be allowed to take delivery of goods up to approximately R10 000 before paying for them. A problem arose whilst the appellant, who was a necessary signatory to the company’s cheques, was on holiday and the company wished to exceed this limit. The company’s project manager, Mr Trollip, testified that a director of the respondent, Mr Humphries, was prepared to allow the company to do so on that occasion but required the company to complete an application for future credit when the appellant returned, because debts owing to the respondent by approved creditors were guaranteed by a third party. Humphries denied that he would have made such a request, his reason being that the respondent had to pay for each creditor subject to the guarantee and a cash customer was obviously preferable for this reason. It is not necessary to resolve the conflict. The fact remains that the respondent must have provided the company’s project manager with its standard credit application form. He completed the form and submitted it to the appellant for signature, and the appellant did sign it. It is common cause that the respondent did not inform Trollip or the appellant that the form imposed a suretyship obligation on the individual who signed it.

[6] The first question is whether the appellant has proved that he was misled. The appellant’s evidence-in-chief was as follows:

‘Now who completed this form? --- Mr Trollip.

But you signed it, what happened in that regard? --- He completed it and he came to me and I saw that there is the said credit application form and being an application form and I saw it is for the debtor for Guzto Log Homes, I signed the document. I did not fill in any dates, it was filled in, I just signed the document.

So what you say, what you saw is you saw the top heading, is that correct, the credit application form? --- Yes.

Did you see the company name Guzto Log Homes (Pty) Limited? --- Yes.

So you accepted therefore that the application was on behalf of Guzto Log Homes? --- True.

That was the applicant. Then you also said that you saw your signature underneath for the debtor? --- Yes.

And who was the debtor? --- Guzto Log Homes.

Did you read through the rest of the document? --- No.

Did you read through the second page, the terms and conditions of sale? --- No.

Did you expect any suretyship agreement or any clause that relates to a suretyship agreement in this document? --- No.

Why not? --- It has been years that I have been filling in application forms, specifically for banks and bonds, you fill in application form, it always without exception they come back to you, they tell you we need A, B, C, D and one of them to be a surety, it was then prepared and make an appointment with you, you sign the surety form.

And that is also besides the bank the position with Thesen and Company? --- Yes.

They did not include any suretyship agreement? --- Yes.

But they granted the, did the credit without a suretyship agreement? --- Yes.

…

If we can return to this specific credit application form, did you expect any surety or clause of suretyship in this agreement? --- No.

And what document did you think had you signed for? --- A credit application form.

On behalf of who? On whose behalf? --- On behalf of Guzto Log Homes.

Were you ever requested by Humphries and Jewell to enter into any suretyship agreement? --- No.

When did you first find out that they, that Humphries and Jewell alleged that you stood surety on behalf of Guzto Log Homes? --- I found a summons at this address that I have given here on this credit application form.

So there was no letter of demand at all? --- No.

So in your experience as a businessman applications for credit that does not include sureties? --- No.

A clause for suretyship? --- No.

Just finally, was it ever your intention to enter into a suretyship agreement? --- No.

And in your opinion did you enter into a suretyship agreement? --- No.

What is your opinion, what did you sign here in this document in this document? --- Application for credit as I did with numerous banks and institutions, they will look at it and come back to you and tell you if they need any further documentation.’

The following passages appear in cross-examination:

‘Would you not agree that the paragraph at the bottom is most conspicuous, one of the first things you recognise on this document, since it is different print and it is in bold and it is in capital letters? --- Well, to be quite honest, the first thing I saw was credit application form.

…

It was never brought, you never thought of it to read the conspicuous part? --- No, because it is an application form and I have done many in the past, they come back to me and they tell me this is what they need. What I did see is for the debtor, for the debtor, obviously I signed for Guzto Log Homes and I signed it.’

In essence the appellant’s evidence was: He saw that according to the heading, the form was an application for credit by the company and he also saw that he was required to sign the form on behalf of the applicant for credit, i.e. the company; but he did not read through the form, he did not realise that it contained a personal suretyship clause and he did not expect it to do so. The appellant also testified that had he realised that the form contained a personal suretyship clause, he would not have signed it ─ he said that he had refused to provide a suretyship in the case of a previous supplier of goods to the company.

[7] The court a quo said (and this is the crux of the judgment):

‘In my opinion I cannot find that [the appellant] was misled by the [respondent’s] representative in any manner whatsoever but simply through his own negligence.’

Counsel on behalf of the respondent interpreted this passage as a finding that the appellant was not in fact misled. I cannot agree. It is plain that the court either found that the appellant was misled, or (at best for the respondent) assumed that he was, and went on to find that the respondent was not responsible. Had the court intended to reject the appellant’s evidence, I would have expected a specific finding in this regard and there is none. Nor was there any cogent argument advanced on appeal as to why the appellant’s evidence should be rejected. I therefore conclude that the appellant acted under a misapprehension in signing the credit application form.

[8] The conclusion just reached does not put an end to the enquiry. In view of the decision in this court in Sonap Petroleum (SA) (Pty) Limited v Pappadogianis 1992 (3) SA 234 (A) 240B it cannot be argued that a signatory’s mistake is justifiable simply because it was induced by the other party. The further question must be asked: Would a reasonable man have been misled? It is this objective enquiry which primarily enables a court to prevent abuse of the iustus error defence in cases such as the present.8

[9] Humphries testified that in his experience a personal suretyship is almost always included in an application for credit on behalf of a corporate entity and his mother and co-director testified that in her experience virtually every application for credit form contains a suretyship agreement. But apart from the respondent’s form, not one such form was produced. The appellant on the other hand testified that his experience in ten years of business was the opposite. According to the appellant he had had several dealings on behalf of the company with third parties (he named Thesen and Co, South African Toilet Hire and Glass Venture Pretoria) where the company applied for credit and a suretyship from him was not required; and in the instances where a suretyship was required, the entities to whom the applications were made (being ‘numerous bankers and institutions’), having evaluated the application, had expressly approved such application, subject to a personal suretyship being given in a separate document, if they required it. The evidence given by the directors of the respondent was specifically challenged in cross-examination. But their evidence was at no stage put to the appellant. It was furthermore not suggested to him that a reasonable businessman would have anticipated a personal suretyship obligation in an application for credit made on behalf of a company. Nor was it put to him that a reasonable businessman could not have expected credit to be granted to a company without some form of security. The appellant said repeatedly that the form was an application form and that if the respondent was only prepared to grant credit subject to security being given, he would have expected the respondent to come back to him. It is after all the company which would have had to provide security if required; and he is not the company. On the facts of this case, the respondent asked for, and was provided with, four trade references. It may be that a reasonable businessman in the position of the appellant could reasonably assume that the respondent, having made enquiries, would not require security in view of the company’s track record with other entities with which it did business. In the absence of a challenge to the appellant’s evidence, I see no reason not to accept it.

[10] The following features of the form are relevant to the question whether a reasonable man would have been misled by it:

(1) The prominent heading of the document proclaims that it is a credit application form ─ not a credit application and personal suretyship. That is in itself misleading. Furthermore, the signatory is not required to sign the form twice, once in each capacity. It is not necessary that a signatory should do so, as a signature can be a ‘double signature’9 but a clear indication that the signatory was signing in two capacities, or, even better, a provision for two signatures with appropriate wording indicating that one is as surety, should eliminate the difficulties which do arise in a case such as the present. Indeed, I have difficulty in understanding why not all of those who draft standard form contracts take these elementary precautions.

(2) The three clauses at the end of the first page are preceded by a phrase which would convey to any person who saw it that the signatory was signing in a representative capacity (‘I, THE UNDERSIGNED ……. IN MY CAPACITY AS ……….. OF THE DEBTOR’); and the place for signature which follows those clauses has the obvious and unmistakable express qualification ‘FOR THE “DEBTOR”’. I attach considerable importance to this latter aspect. The attention of the signatory would inevitably be drawn to these parts of the form as they had blanks requiring completion.

(3) It is true that the third clause, which contains the personal suretyship, is in capitals (it does not seem to me to be in bold type as found by the court a quo), but so also are the two clauses which precede it; and the emphasis of the suretyship clause is thereby diminished. The third clause also immediately precedes the place for signature, but it is part of a block of three clauses and therefore not as conspicuous as it would have been standing on its own or were it to have been in red ink.10 The manner in which the personal suretyship clause has been included in the form would accordingly not suffice to alert a signatory to the fact that he/she was undertaking a personal obligation despite the heading of the form, despite the wording which preceded the block of clauses of which the suretyship clause formed a part, and despite the qualification to the signature ─ which stands on its own, is in capitals and would be obvious to anyone signing the document ─ which followed those clauses.

[11] In my view the form was a trap for the unwary and the appellant was justifiably misled by it. Ms Humphries’ evidence in cross-examination that the form had been used by the respondent for 15 years and that no-one had ever told her that it was a trap does not incline me to depart from the conclusion I have reached. It is true that the appellant had ample opportunity to read the form carefully and he did not avail himself of that opportunity. But that is no answer. It is not reasonable for a party who has induced a justifiable mistake in a signatory as to the contents of a document to assert that the signatory would not have been misled had he read the document carefully; and such a party cannot accordingly rely on

the doctrine of quasi-mutual assent.

[12] I conclude that the respondent’s conduct in furnishing the form, which was misleading, induced a fundamental mistake on the part of the appellant: He thought he was signing a credit application form on behalf of the company, whereas he was, in addition, undertaking a personal suretyship for the debts of the company. It follows that the suretyship obligation was void ab initio and that the appeal must succeed.

[13] I make the following order:

(1) The appeal is allowed with costs.

(2) The order of the court below is set aside and the following order substituted:

‘The plaintiff’s claim is dismissed with costs.’

______________

T D CLOETE

JUDGE OF APPEAL

Concur: Mpati AP

Farlam JA

Jafta AJA

NAVSA JA:

[14] I have had the benefit of reading the judgment of Cloete JA. I differ with him on his conclusion that the appellant was entitled to escape liability because he was under a misapprehension caused by the respondent, more particularly by way of the form embodying the credit application and the suretyship. The difference between us relates to the application of the law to the facts of the case.

[15] It is regrettable that Motata J made no findings of credibility and said nothing about the probabilities. However, we do have the benefit of the record of the evidence that was led in the Court below and are in as good a position as that court to arrive at the correct decision.

[16] In Sonap Petroleum (SA) (Pty) Ltd formerly known as Sonarep (SA) (Pty) Ltd v Pappadogianis (3) SA 234 (A) JA at 239I-240B summarised the decisive question in cases such as the one under discussion:

‘In my view, therefore, the decisive question in a case like the present is this: did the party whose actual intention did not conform to the common intention expressed, lead the other party, as a reasonable man, to believe that his declared intention represented his actual intention? …To answer this question, a three-fold enquiry is usually necessary, namely, firstly, was there a misrepresentation as to one party’s intention; secondly, who made that representation; and thirdly, was the last party misled thereby?….The last question postulates two possibilities: Was he actually misled and would a reasonable man have been misled? Spes Bona Bank Ltd v Portals Water Treatment South Africa (Pty) Ltd1983(1) SA 978 (A) D-H, G-H.’

[17] To answer the question one must of necessity consider the totality of the relevant evidence. I proceed to deal with relevant parts of the evidence.

[18] Ms Humphries, the mother of the Mr Humphries referred to in para [5], is also a director of the respondent. She testified without challenge that the credit application form in question had been used by the respondent for ‘years and years’. Later in her evidence she stated that the present form had been used in the respondent’s business for fifteen years and that no-one had complained about it being a trap. She also testified that in her experience in business every creditor has a suretyship embodied in the application form.

[19] Cloete JA did not find it necessary to resolve the conflict about who initiated the signing of the application form. It is clear from the evidence, however, that the appellant’s absence at a time when his signature was required for the payment of a consignment of wood that was urgently needed is what led to the application form being completed. This was done to obviate problems in future. It is therefore fair to say that the respondent was not the driving force behind the completion of the form. It is clear that no pressure was applied by the respondent for the completion of the form within a specified period of time.

[20] The company’s project manager described the appellant as a ‘brilliant businessman’ but negligent. He testified that he was inclined to sign documents without reading them.

[21] When the appellant testified, he referred to an application to open an account with Thesen & Co (Pty) Ltd, as an example of how he was not required in his business dealings to complete a suretyship form when applying for credit. An examination of that form indicates that as security for amounts due there is a reservation of ownership clause and an accompanying cession in securitatem debiti. Carefully scrutinised the evidence reveals that the only credit application form (other than in respect of the overdraft facility) that had been signed by the appellant on behalf of the company, other than the present one, was the one referred to earlier in this paragraph.

[22] At para [6] Cloete JA deals extensively with the appellant’s evidence concerning the completion of the form and how he was misled. The third question referred to is a very leading one. So are the fifth and the sixth. The appellant’s evidence in this regard must therefore be assessed against the manner in which it was extracted. Furthermore, in response to the eleventh question set out by Cloete JA in para [6], as to why the appellant did not expect a suretyship clause in the agreement, he referred to his years of experience in filling in application forms ‘specifically for banks and bonds’ and stated that ‘they’ tell you who they require as a surety. This experience did not relate to suppliers of goods. Later, under cross-examination, he repeated that his exposure in this regard was with banks. He stated specifically that ‘it was % with banks’.

[23] The twenty-first question referred to in para [6], about whether in the appellant’s ‘experience as a businessman’, applications for credit included surety clauses is, once again, leading and beyond the limited experience referred to by the appellant himself. The evidence by the appellant under cross-examination, referred to in para [6], must be seen against this background.

[24] The appellant’s testimony, that he was loath to sign suretyships for the company as it was not well-established, has to be weighed against the fact that he signed as surety for an overdraft facility with a bank. When he testified about signing as surety for the overdraft facility he stated that it was common knowledge for any bank to request a suretyship for the facility ‘especially of a company and close corporation’.

[25] Even though the appellant testified that in his experience a suretyship document was presented separately from a credit application form, it is clear that he was aware that security for the granting of credit facilities, particularly in respect of companies and close corporations, was a concern for those granting credit facilities.

[26] It is clear that at the time that the application form was signed the appellant knew that the company was applying for a credit facility up to a maximum of R50 000-00. It is common cause that the facility was later increased at the instance of the appellant, first to an amount of R100 000-00 and later to R150 000-00.

[27] Under cross-examination the appellant testified that he had read some of the credit applications he had completed during the years he had been involved in business. His categorical denial that none of the forms he signed contained a suretyship must be seen against that evidence.

[28] The appellant, as noted by Cloete JA, relied solely on the form as having induced his misapprehension. The form, a copy of which is attached to Cloete JA’s judgment, requires closer scrutiny. It is not long or complicated. It will be noted that all three clauses above the signature are in capitals and in bold and that those clauses (other than the company logo and name, the title of the document, and the words ‘PRIVATE AND CONFIDENTIAL’) are the only parts of the document in capitals and in bold. The terms and conditions on the reverse side are not in capitals and are in much smaller print. It is therefore fair to describe the three clauses, including the suretyship, as being prominent.

[29] That explains why, when the appellant was asked under cross-examination whether he agreed that the part of the credit application form that contained the suretyship clause was conspicuous, he was evasive: ‘Well, to be quite honest, the first thing I saw was the credit application form.’.

[30] Cloete JA regarded it as important that what is indicated in the introductory part, immediately above the three clauses, is the capacity in which the appellant signed, namely as director of the company. Credit up to a limit of R50 000-00 was being applied for by the company. That is what was intended by both parties. The appellant signed on behalf of the company which is clearly identified as the debtor. The suretyship clause is located approximately 1 cm below the space where the debtor is identified. The appellant’s signature is immediately below the suretyship clause and extends over it. Part of the appellant’s signature extends over the words ‘CO-PRINCIPAL DEBTOR’ and is approximately 2 cm away from the word ‘SURETY’.

[31] In an article entitled ‘INAPPROPRIATE WORDING IN A CONTRACT: A BASIS FOR THE DEFENCE OF IUSTUS ERROR?’ (1989) 106 SALJ 458 RD Sharrock, in dealing with the Keens Group case, puts forward the proposition that the conclusion, that the provisions of the document in that case were misleading, is open to criticism. The author argues that the document in question in that case was primarily an application for credit facilities by an individual on behalf of a company and it could be expected that it would be headed ‘Application for credit facilities’ and that it would contain details relating to the company. The execution clause could be expected to be signed on behalf of the company by someone authorised thereto who would warrant his authority. Sharrock submits that the suretyship clause located as it was in that document was not out of place or at variance with the purpose of the document.

[32] Sharrock argues that it is surely not unexpected that when a company applies for credit a senior director or person in control of the company’s affairs would be required to provide a suretyship.

[33] In para [8] of Cloete JA’s judgment, in discussing the Sonap case, he states that the question whether a reasonable man would be misled, is the means to prevent abuse. In a related footnote he states that this is an aspect that Sharrock overlooked. First, Sharrock wrote the article referred to in the preceding paragraphs at a time before the judgment in the Sonap case, when the focus had not been fully on asking whether a reasonable man would have been misled ─ the problem was viewed simply from the perspective of whether the party seeking to resile had led the other party to an agreement, as a reasonable person, to believe that he was binding himself. In the Sonap case this question was held to be multidimensional. Second, Sharrock was concerned with how a party who had not read a document could claim to have been misled by it. Third, Sharrock, in any event, in asking the questions referred to earlier, was holding the assertions of the party seeking to resile up to objective scrutiny.

[34] While courts should come to the rescue of parties who have been misled or induced to enter into agreements of the kind under discussion they should be mindful of what was stated in National & Overseas Distributors Corporation (Pty) Ltd v Potato Board 1958 (2) SA 473 (A) at 479G-H:

‘Our law allows a party to set up his own mistake in certain circumstances in order to escape liability under a contract into which he has entered. But where the other party has not made any misrepresentation and has not appreciated at the time of acceptance that his offer was being accepted under a misapprehension, the scope for a defence of unilateral mistake is very narrow, if it exists at all. At least the mistake (error) would have to be reasonable (justus) and it would have to be pleaded. In the present case a plea makes no mention of mistake and there is no basis in the evidence for a contention that the mistake was reasonable.’

See also Christie The Law of Contract(4 ed 2001) 365 where the following appears after a discussion of this case:

‘This summary of the law is borne out by the cases, which show the possibility of iustus errorto be very limited, unless the other party knew or ought to have known of, or caused the mistake.’

[35] In my view, the form seen as a whole cannot be described as a trap or as a misrepresentation. It is unlikely that a ‘brilliant businessman’ like the appellant could have thought that credit in an amount of R50 000-00 would be extended to a private company without any security. Against the background referred to above the respondent would have been reasonably entitled to believe that the appellant was assenting to be bound as surety for the company’s debts. The appellant’s evidence, as referred to in para [6], was that he was told by Trollip that what was being presented to him was a credit application form and he saw that it was for Guzto Log Homes as the debtor and that he just signed the document. That evidence must be measured against the fact that the company was now applying for credit facilities, increased fivefold, and his knowledge that businesses required suretyships in respect of private companies and corporations. It must also be seen against simplicity of the form and the prominence of the suretyship clause and the extension of his signature across that clause.

[36] Even if one were to accept that the appellant was somehow misled by the heading of the document, the question whether a reasonable man would have been misled, must, in my view, against the background referred to earlier, be answered against the appellant (See the dictum in the Sonap case in para [16] above). To permit the appellant in this case, against the form in question, and against the factors set out earlier, to escape liability, is in my view, to open the door to abuse and possible uncertainty.

[37] In my view the appellant failed to discharge the onus of showing that his error was iustus and consequently the appeal should be dismissed with costs.

_________________

MS NAVSA

JUDGE OF APPEAL

1 Described as a ‘sound principle of law’ by Innes CJ (Solomon and Wessels JJ concurring) in Burger v Central South African Railways 1903 TS 571 at 578 in a passage approved in George v Fairmead (Pty) Limited1958 (2) SA 465 (A) 470B-E.

2 Above n 1 at 471A-D.

3 See also Spindrifter (Pty) Limited v Lester Donovan (Pty) Limited 1986 (1) SA 303 (A) 316I-J.

4 Absent a contractual term precluding reliance on the representation : see the majority decision in Trollip v Jordaan 1961 (1) SA 238 (A).

5 Allen v Sixteen Stirling Investments (Pty) Limited 1974 (4) SA 164 (D); Janowski v Fourie 1978 (3) SA 16 (O); Moresky v Morkel 1994 (1) SA 249 (C).

6 It is not necessary to consider the position where the misapprehension has been caused by a third party.

7 As in Keens Group Co (Pty) Limited v Lötter 1989 (1) SA 545 (C).

8 This aspect appears to have been overlooked by Sharrock in his criticism of the Keens case (above, n 7) in ‘INAPPROPRIATE WORDING IN A CONTRACT: A BASIS FOR THE DEFENCE OF IUSTUS ERROR?’ (1989) 106 SALJ 458 especially at 463.

9 Glen Comeragh (Pty) Limited v Colibri (Pty) Limited 1979 (3) SA 210 (T) at 214F─ in fine.

10 Cf Keens above n 7 at 591A-B, and contrast Roomer v Wedge Steel (Pty) Limited 1998 (1) SA 538 (N) at 543G-I.