THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEAL

OF SOUTH AFRICA

Case number : 69/06

REPORTABLE

In the matter between :

ANDRIES PETRUS LUBBE NO First Appellant

WILLEM PETRUS LUBBE NO Second Appellant

HILTON SAVIN NO Third Appellant

PAUL OLIVER SAUER MEAKER NO Fourth Appellant CORRIDA HOLDINGS (PTY) LIMITED Fifth Appellant CORRIDA SHOES (PTY) LIMITED Sixth Appellant

and

MILLENNIUM STYLE (PTY) LIMITED First Respondent

BRETT GEORGE HODGSON NO Second Respondent

PULSE POLYURETHANE MANUFACTURERS

(PTY) LIMITED ` Third Respondent

GUY BOWMAN Fourth Respondent

and in the matter of a counter-application between:

ANDRIES PETRUS LUBBE NO First Appellant

WILLEM PETRUS LUBBE NO Second Appellant

HILTON SAVIN NO Third Appellant

PAUL OLIVER SAUER MEAKER NO Fourth Appellant

and

MILLENNIUM STYLE (PTY) LTD Respondent

CORAM : HARMS ADP, BRAND, CLOETE, PONNAN AND CACHALIA JJA

HEARD : 23 FEBRUARY 2007

DELIVERED : 16 MARCH 2007

Summary: Trade marks – expungement – devices and shapes

Neutral Citation: This judgment may be referred to as Lubbe NO v Millennium Style [2007] SCA 10 (RSA)

JUDGMENT

HARMS ADP:

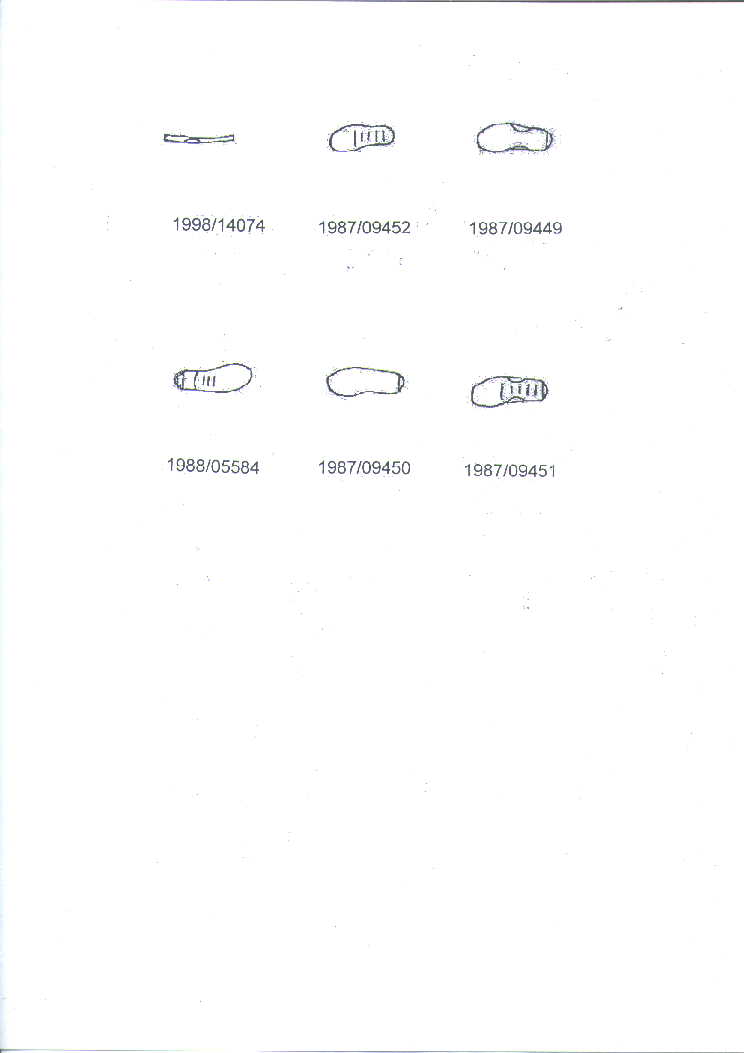

[1] This is a trade mark case. Msimang J, sitting in the high court, dismissed an application for an interdict based on trade mark infringement of six trade marks1 that belong to a Trust represented by its trustees. In response to a counter-application for the rectification of the trade mark register he ordered that the marks be expunged. He consequently dismissed the infringement application having found in addition that there could in any event not have been any infringement. He granted leave in relation to the expungement only but this Court extended the scope of the appeal by granting leave in relation to the infringement.

[2] There are cyber-squatters and there are those who squat on the trade mark register. Judged by the papers in this case the Trust is an entity that used the register to stifle competition and not for its statutory purpose. The fact that there is no opposition to an application for registration or that there is not already something similar on the register does not mean that the application should proceed to grant.

[3] This practice gives intellectual property law a bad name. It also throws serious doubt on whether this part of the law covers anything intellectual. Significantly, a few days before the hearing of the appeal the Trust admitted that two of its marks did not have the ability to distinguish but nevertheless sought to prevent their expungement on technical grounds. The reader may be surprised to know that the Registrar had registered the one (TM 1987/9450) in Part A of the register in terms of the Trade Marks Act 62 of 1963, which meant that the Registrar was at the time satisfied that the mark was distinctive. Maybe I should surprise the reader further by describing this particular trade mark: it is a device for a shoe sole and the device consists of a single transverse stripe towards the end of the heel. The other mark (TM 1998/14074) covered by the Trust’s concession is simply the side view of a shoe sole.

[4] But this case is not really about trade marks. It is about the suppression of competition. The appellants are upset because a former employee went into competition with them by making shoes that by virtue of their design and construction and overall appearance are ‘an almost direct copy’ of a shoe made by or under licence from the Trust. As said by the main deponent on behalf of the appellants, Mr AP Lubbe, their case is essentially a simple one: the trade marks are infringed because the respondents use the distinctive characteristics of the appellants’ sole construction. Their unfair competition case, it need be stated, fell apart in the high court and no attempt was made to rebuild it.

[5] The appellants’ case invited an attack on the five trade marks registered in Part A of the register under the 1963 Act on the ground that in each instance the shape and configuration of a shoe sole was registered, something not permitted by the 1963 Act. The appellants responded vehemently by stating that they were entitled to register the shape and configuration of a sole as a trade mark because it is a ‘device’.

[6] In cannot be gainsaid that shapes were not registrable under the 1963 Act as trade marks and calling shapes ‘devices’ made no difference to the conclusion. See Weber-Stephen Products Co v Registrar of Trade Marks 1994 (3) SA 611 (T) at 615G-I; cf Koninklijke Philips Electronics NV v Remington Products Australia Pty Ltd [2000] FCA 876 para 16. But, submitted counsel for the appellants, we must ignore what the appellants had said about the meaning of their trade marks because what was indeed registered were devices, i.e., visual representations or illustrations capable of being reproduced on a surface, whether by printing, embossing, or by any other means (s 2(1) ‘device’). To explain the difference: the appellants’ case on the papers was that the transverse stripe referred to represents an indication that the end of the heel is bevelled. Now the argument is that the stripe is simply a stripe printed or embossed on a sole. The argument becomes odd if regard is had to TM 1988/05584. It clearly shows an ordinary heel of a shoe plus three stripes of no particular distinctiveness. Counsel had to submit that what was obviously intended to be a heel was in reality the impression of a heel but that the use of a real heel would also infringe.

[7] This aspect of the case can be disposed of on two bases. The first is this. The admission, disclaimer, memorandum, limitation or condition of each of these registrations begins with this statement:

‘Die merk bestaan uit die devies van die patroon van ‘n SOOL, wat toegepas word op ‘n SKOEISEL.’

Translated, it means that the mark consists of a device of the design of a sole applied to footwear. There is a big difference between a device which has to be applied onto a sole (which could have been registered) and a design of a sole (which could not). The wording confirms what the marks were obviously intended to represent, namely the design of a sole, and how the appellants impermissibly sought to enforce them.

[8] Once the conclusion is that these marks were not registrable under the 1963 Act, they have to be expunged. Under s 70 of the Trade Marks Act 194 of 1993, the validity of the original entry of a trade mark on the register existing at the commencement of this Act must be determined in accordance with the law then in force. Section 42 of the 1963 Act provided that (subject to certain exclusions) trade marks registered in Part A are to be taken as valid in all respects after seven years. One exclusion was if the trade mark offended against s 16 which, in turn, prohibited a registration ‘contrary to law’. The registration of the shape of an article was at the time contrary to law because only ‘marks’ as defined (which excluded shapes) could be registered.

[9] The second basis relates to the trade mark value of distinctive shoe soles and devices for soles. Under the 1993 Act devices, shapes and configurations may be registered as trade marks. But the mere fact that they may be distinctive does not mean that they are distinctive in the trade mark sense, i.e. to indicate source of origin. Typically the pattern or shape of a shoe sole would be regarded by the purchaser as either ornamental or as part of the design of the shoe tread and it is seldom that it will be considered to be a source identifier. The respondents’ evidence to this effect was not and could not be gainsaid in any meaningful way. Indeed, if regard is had to the fact the appellants have not in twenty years used any of these marks as trade marks the conclusion becomes irresistible. (I shall refrain from asking why the marks were not attacked on the ground of non-use.) See Bergkelder Bpk v Vredendal Koöp Wynmakery [2006] SCA 8 (RSA) para 8-9; cf Adidas-Salomon AG v Fitnessworld Trading Ltd Case C-408/01 (ECJ) para 38-42. Attached to this judgment is a representation of all these marks and it will be obvious from a mere glance that not one of the devices has any trade mark significance and that they would be perceived by the public as sole tread designs, whether functional or aesthetic. Because these marks are accordingly not capable of distinguishing in the trade mark sense they have to be expunged from the register. See Bergkelder Bpk at para 14.

[10] Turning then to TM 1998/14074 which, as mentioned, consisted of the side view of a shoe sole and which the appellants concede was and is incapable of distinguishing, the case of the appellants is that the mark should not have been expunged because the respondents are no longer persons interested in the mark. This, according to the argument, is because the appellants no longer rely on its infringement and because the respondents do not allege that they wish to use that representation. This argument, which was eventually not persisted in, can nevertheless be disposed of in a few words. The question whether a party is an ‘interested person’ entitled to apply for the rectification of the register under s 24 of the 1993 Act is determined at the time of litis contestatio and once a party has legal standing, the other party cannot by its action destroy the first mentioned party’s standing. The other reason is this: a person in the trade area covered by the impugned trade mark is in principle an interested party because such a person has an interest in having the register clear of objectionable registrations. Cf Ritz Hotel Ltd v Charles of the Ritz Ltd 1988 (3) SA 290 (A) at 307H-308E and Mars Inc v Candy World (Pty) Ltd 1991 (1) SA 567 (A) at 574C.

[11] The question may fairly be asked why such a simple case has reached this Court, especially after Galgut DJP had already held at the interlocutory stage that the appellants do not have a prima facie case. In spite of the record of some 650 pages it should not have, but the complexity of the argument presented below and in the heads of argument may provide part of the answer.

[12] The appeal is dismissed with costs, including those consequent upon the employment of two counsel.

________________________

L T C HARMS

ACTING DEPUTY PRESIDENT

AGREE:

BRAND JA

CLOETE JA

PONNAN JA

CACHALIA JA

1TM 1998/14074; 1987/9452; 1987/9449; 1988/5584; 1987/9450; and 1987/9451, all registered in Class 25 in respect of footwear.