REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA

THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEAL

OF SOUTH AFRICA

REPORTABLE

Case number: 503/06

In the matter between:

VARI-DEALS 101 (PTY) LTD

t/a VARI-DEALS First Appellant

JILL BELINDA DRAKE Second Appellant

ZIMSTONE (PTY) LTD t/a ZIMSTONE Third Appellant

KEITH ARNOLD MUNRO Fourth Appellant

UWE FRITZ Fifth Appellant

and

SUNSMART PRODUCTS (PTY) LTD Respondent

CORAM: HARMS ADP, NUGENT, PONNAN,

COMBRINCK JJA and HURT AJA

HEARD: 3 SEPTEMBER 2007

DELIVERED: 27 SEPTEMBER 2007

Summary: Patent – Interpretation of specification and claims – 'Purposive approach' – Patent and Registered Design – Anticipation – Infringement.

Neutral citation: This judgment may be referred to as Vari-Deals 101 (Pty) Ltd v Sunsmart Products (Pty) Ltd [2007] SCA 123 (RSA)

_____________________________________________________________________

JUDGMENT

_____________________________________________________________________

HURT AJA:

Introduction.

[1] The respondent, Sunsmart Products (Pty) Ltd (‘Sunsmart’), is the proprietor of a registered patent and a registered design. Since 2004, various courts have dealt with applications for interdicts and related relief, claimed by Sunsmart on the basis that the patent and design have been infringed. It is convenient, at the outset, to recount the history of this litigation for the purpose of clarifying certain of the issues which require to be dealt with in this appeal.

[2] During November 1997, applications for registration of the patent and the design were lodged under numbers 97/10535 and 97/1155, respectively, with the Registrar of Patents and the Registrar of Designs. Both applications related to what was described as a ‘flag construction’. During 2002, the original proprietors of the patent and the registered design executed assignments of their rights in both to Sunsmart. In 2004 Sunsmart brought two applications for interdicts restraining the infringement of the patent and the registered design against various alleged infringers. The respondent in the first of these was a company called Flag and Flagpole Industries (Pty) Ltd. In that case simultaneous applications were lodged in the Court of the Commissioner of Patents (under case no 97/10535) and in the High Court, Pretoria (under case no 7385/04). In a second (later) application, the five appellants in this appeal were amongst seven cited respondents who were alleged to have infringed the patent and the registered design. The second application was likewise launched in the Commissioner's Court (also under case no 97/10535) and in the High Court (under case no 21061/04). In each of these applications, a judge sat in the dual capacity of the Commissioner and of a judge of the High Court. In what has become known (and will be referred to in this judgment) as ‘the Flag and Flagpole case’, the presiding judge was Southwood J and in the court from which this appeal emanates, R D Claassen J presided.

[3] In the Flag and Flagpole case, the respondent denied infringement and, in the alternative, contended that both the patent and the design were invalid for want of novelty. Southwood J held that Sunsmart had failed to prove infringement of the patent because one of the essential elements of the invention claimed in the patent was not incorporated in the Flag and Flagpole product. He therefore found it unnecessary to deal with the issue of validity of the patent. In regard to the design, Southwood J held that a ‘sail flag’ described and illustrated in a 1992 United States Patent (‘the Rehbein Patent’) constituted an anticipation of the registered design and he accordingly dismissed the application for an interdict on that score. Southwood J granted leave to appeal against his judgment.

[4] The applications which were dealt with in the court a quo by Claassen J, came before him after they had been referred for the hearing of oral evidence in regard to a factual dispute relating to the issue of whether certain of the cited respondents had been guilty of ‘contributory infringement’. The matter proceeded before Claassen J while the appeals against the decisions by Southwood J were still pending. I should mention that, on the papers before Claassen J, there was a counter-application for revocation of the patent on the basis that it was invalid.

[5] After hearing evidence, Claassen J held that Sunsmart had established infringement of the patent and of the design. In the course of reaching his conclusions as to infringement, Claassen J found himself constrained to disagree with the construction placed on the claims in the patent by Southwood J and with Southwood J's finding that the design was not novel. He found that there had been infringement (both ‘direct’ and ‘contributory’) of the design and the patent and granted the customary relief. In addition, he granted an unusual order, directing the respondents to disclose to Sunsmart the names of other possible infringers to whom the respondents had sold their products. Insofar as his finding was to the effect that there had been contributory infringement (the issue which had been referred for the hearing of viva voce evidence), his conclusion was that the first, third, fourth and fifth respondents had colluded to procure the infringement. As there had apparently been no mention, in the course of argument before him, of the counter-application for revocation, Claassen J made an order dismissing it. His judgment was delivered on 30 January 2006. He, too, granted leave to appeal to this court.

[6] On 16 March 2007, the appeal to this court in the Flag and Flagpole matter was heard. Judgment on the appeal (per Streicher JA) was handed down on 3 April 2007.1 The unanimous decision of this court was that Southwood J had erred in finding that there was no infringement of the patent. On this basis it became necessary for the court to consider the issue as to the validity of the patent. In this regard, the contention was that US Patent 5 572 945, applied for in August 1994 (‘the Eastaugh Patent’) described the invention in SA Patent 97/10535 and rendered it invalid for want of novelty. This contention was rejected. Insofar as the design was concerned, this court dismissed various contentions to the effect that the design had been described or depicted in various earlier documents and drawings (including the Rehbein patent). The court decided that the appeals in both the patent and design cases should be upheld and granted relief by way of interdicts, orders for delivery of infringing articles and an enquiry into damages.

[7] For some reason, the second respondent in the court a quo, against whom Sunsmart had withdrawn its claims, was cited as the second appellant in this appeal. In fact, there are only four appellants before us and, as was done in the High Court, it will be convenient to refer to them by name, viz, the first appellant, Vari-Deals 101 (Pty) Ltd, as ‘Vari-Deals’, the third appellant, Zimstone (Pty) Ltd, as ‘Zimstone’, the fourth appellant, Mr Keith Arnold Munro and the fifth appellant, Mr Uwe Fritz, by their surnames, ‘Munro’ and ‘Fritz’ respectively.

The Effect of the Flag and Flagpole Judgment.

[8] The appellants' heads of argument were submitted to this court on 5 April 2007, only two days after the judgment in the Flag and and Flagpole appeal was handed down. The appellants, having based their original argument on the judgments of Southwood J, submitted a set of supplementary heads in order to deal with the situation which had developed as a result of the reversal by this court of those judgments. In the introduction to the supplementary heads, the appellants stated:

‘These supplementary heads have been prepared in an attempt to address the judgment of this honourable court in the Flag and Flagpole matter insofar as it relates to both the patent and the design cases. The submission will be, for the reasons which follow, that this honourable court is not bound to follow its earlier decision, and that this decision notwithstanding, the present appeal should succeed on both the patent and design cases.’

There followed a number of submissions by counsel for the appellants to the effect that this court erred in coming to its conclusions in the Flag and Flagpole matter –

(a) by failing to apply the proper principles of construction of patent claims when considering the meaning and scope which should be attributed to them;

(b) by incorrectly rejecting the contention that the invention in the patent was not new, inasmuch as it had been ‘described’ (within the meaning of that expression in s 25(6) of the Patents Act 57 of 1978) in the Eastaugh patent;

(c) by finding that all of the essential integers in claim 1 of the patent are present in the allegedly infringing flag;

(d) by finding that the registered design had not been anticipated by one of the drawings in the Rehbein patent. (Section 35(5), read with s 31(c) and s 14 of the Designs Act 195 of 1993.)

[9] In view of these submissions, it is perhaps not inapposite to bear in mind (trite though the proposition may be) that this court is not sitting as some sort of ‘Second Court of Appeal’ in judgment on the Flag and Flagpole case. The judgment in that case, insofar as it concerns the interpretation of the specification and/or claims of SA Patent 97/10535 and insofar as it incorporates findings that the patent and the registered design had not been anticipated by the Eastaugh and Rehbein patents respectively defines rights of a statutory nature which apply as between Sunsmart and the public at large, and not merely between the parties to the litigation. Especially in this situation, this court would accordingly only be justified in declining to follow the interpretations and the rulings on anticipation (or rather the absence thereof) in the Flag and Flagpole judgment in very restricted circumstances. These are concisely stated in Bloemfontein Town Council v Richter 1938 AD 195 at 232 viz :

'The ordinary rule is that this court is bound by its own decisions and unless a decision has been arrived at on some manifest oversight or misunderstanding that is there has been something in the nature of a palpable mistake, a subsequently constituted court has no right to prefer its own reasoning to that of its predecessor - such a preference, if allowed, would produce endless uncertainty and confusion. The maxim 'stare decisis' should, therefore, be more rigidly applied in this, the highest court of the land, than in all the others.'

This approach has been regularly applied in our law.2 Counsel for the appellants, though invited to do so, refrained from contending that the judgment in the Flag and Flagpole case was tainted by the type of oversight or error contemplated in the above passage.

[10] Counsel did, however, persist in a submission to the effect that the approach of this court in the Flag and Flagpole case had not been consistent with South African law and that, in considering the issue of infringement in this case, we should have regard to the caution expressed by Plewman JA in Nampak Products Ltd and Another v Man-Dirk (Pty) Ltd 1993 (3) SA 708 (SCA) at 712-714. Counsel's submission, as I understood it, was that the tendency to ‘purposive construction’ of patent specifications and claims in English law3 had been affected by the introduction of s 125 of the English Patents Act of 1977 and Article 69 of the European Patent Convention. These statutory provisions had, and have, no force in this country, with the result that the developments pursuant to them were not applicable to the interpretation of patents by our courts. The result would be that the ‘time-honoured approach’ to interpretation in our law4 needed to be, but was not, applied in the Flag and Flagpole case. Without going so far as to ask this court to disapprove of the interpretation given to the claims in the Flag and Flagpole case, counsel suggested that, for the purpose of deciding the infringement issue before us, we should revert to the more ‘literal’ approach and minimize the role which the apparent intention of the patentee might play in deciding what the claims mean and which particular aspects of them should be regarded as ‘essential elements or integers’.

[11] There are two crisp answers to this suggestion.

(a) The primary object of Plewman JA's comments in regard to the changes in approach to interpretation was to stress that the advent of ‘purposive construction’ should not be treated as giving litigants carte blanche to tender the evidence of expert witnesses as an aid to the construction of claims (p 714B). Nowhere, in the relevant passage, did the learned Judge disapprove of the Catnic approach – he simply cautioned that it should be applied with care (p 714 D-E).

(b) In Aktiebolaget Hässle and Another v Triomed (Pty) Ltd 2003 (1) SA 155 (SCA), Nugent JA, after a brief review of the cases, said (at p160 para [9]):

‘While the claim must be construed to ascertain the intention of the inventor as conveyed by the language he has used (Gentiruco AG v Firestone (Pty) Ltd 1972 (1) 589 (A) at 614 B-C) what is sought by a purposive construction is to establish what were intended to be the essential elements, or the essence, of the invention, which is not to be found by viewing each word in isolation but rather by viewing them in the context of the invention as a whole. To the extent that it might have been suggested in an obiter dictum in Nampak Products Ltd and Another v Man-Dirk (Pty) Ltd 1999 (3) SA 708 (SCA) at p 714A that it might be called in aid only to construe an ambiguous claim, I do not think that is supported by the decisions of this court and, in my view, it is not correct.’

That the ‘purposive approach’ has received the authoritative endorsement of the courts in this country was made clear by Nugent JA in his review of the South African decisions (and and their adoption of the Catnic approach) at pages 159 to 160 of Triomed. It is, of course, true that Catnic did not change the law relating to construction5, but it certainly restricted the scope for contesting litigants to indulge in ‘meticulous verbal analysis’ of specifications and claims - usually to an extent which would have been inconceivable to the ordinary skilled addressee reading the patent to ascertain the invention and the ambit of protection claimed. It also relieved the courts of the metaphorical ‘straitjacket’ of having to arrive at any interpretation of claims without having free recourse (subject to the well-established limits) to the specification in order to decide what the skilled addressee would have understood those claims to mean.6

[12] In reaching his conclusions as to the meaning of the claims in the patent, Streicher JA expressly applied a purposive interpretation. In doing so he relied upon the Triomed judgment and there is no basis for the criticism leveled at him in this respect by counsel for the appellants.

The Patent-in-Suit.

[13] The first exercise must be to consider the specification of the patent and to decide on the meaning and scope of the monopoly defined by the claims.

[14] Fundamentally, the patentee seeks protection for a new type of flag which will remain extended, whatever the weather conditions, and which is of particular use as an advertising medium. The specification records that the flags of the prior art had two specific drawbacks in this context. The first was that they remained limp in windless conditions, making it impossible to decipher any advertising copy which might be printed on them. The second was that in high wind conditions, or in blustery weather, the continual flapping of the flag would also result in difficulty in reading the advertiser's message and would also often result in damage to the flag material. The patentee's claim is to a method (and to its resultant product) of keeping the material of the flag extended in any type of weather conditions by using a flexible pole to apply tension to the material. The consistory clause reads as follows:

‘According to the invention, a flag construction comprises a pole which includes, at least at the top end thereof, a flexible section which is adapted to be bent into a substantially U-shaped section and being adapted to engage at least a portion of the upper periphery of a piece of material and to maintain it under tension at least in the area defined by the pole, the U-shaped section and a line between a point towards the tip of the flexible section and a point along the length of the pole.’

The specification then proceeds to describe various preferred embodiments and/or modifications which are all to be discerned in the claims and it will be convenient to deal with those that are relevant in this case when the meaning and scope of the claims are considered.

[15] The claims read as follow:

‘1. A flag construction comprising a pole which includes, at least at the top end thereof, a flexible section which is adapted to be bent into a substantially U-shaped section and being adapted to engage at least a portion of the periphery of a piece of material and to maintain it under tension at least in the area defined by the pole, the U-shaped section and a line between a point towards the tip of the flexible section and a point along the length of the pole.

2. The flag construction according to claim 1 in which the top end of the pole includes a flexible section of fibreglass or the like which tapers to a narrow diameter.

3. A flag construction according to claim 2 in which the tapered section is integral with the pole.

4. The flag construction according to claim 3 in which the material includes a seam or sleeve along one edge, into which the tapered end of the pole is slided (sic).

5. A flag construction according to any of the above claims including the combination of an inverted U-shaped section with an inverted teardrop-shaped piece of material.

6. A flag construction according to any of the above claims in which the pole is adapted to rotate about its own axis.

7. A flag construction substantially as described with reference to the accompanying drawing.’

The issues relating to the meaning and scope of the claims in this case are restricted and it is not necessary for the purpose of this judgment to embark on an exhaustive analysis and interpretation. It will be convenient, instead, to consider the proper interpretation in relation to each of the issues as they are dealt with.

Alleged Invalidity of the Patent.

[16] Before us the appellants persisted with the contention that the patent was anticipated by the Eastaugh patent. Certain submissions were made concerning the analysis of the Eastaugh patent by this court in the Flag and Flagpole case. The submissions fall to be rejected on the simple basis of stare decisis: the interpretation of the Eastaugh patent is a question of law and the appellants have not been able to pass the hurdle set in the Bloemfontein Town Council judgment.7

[17] I have already indicated that the counterclaim for revocation of the patent was dismissed by Claassen J. Counsel for the appellants contended that, inasmuch as the revocation proceedings had not reached a stage where they were ripe for adjudication at the time when Claassen J delivered his judgment, they should not have been dismissed but left in abeyance. As stated by Claassen J, however, no submissions were made to him in relation to the prayer for revocation and in the circumstances, given that he was called upon to adjudicate upon the application (including the counterclaim for revocation) it was proper for him to make the order dismissing the latter. Such an order, of course, does not stand as res judicata on the issue of revocation, but given the findings of the courts in relation to the issue of validity of the patent when raised as a defence to the claim for infringement, it is highly doubtful whether the revocation application, if proceeded with separately, would have any prospect of success.

Infringement of the Patent.

[18] The issue of infringement in this case has been complicated by Sunsmart's contention that the appellants collaborated and induced others to assist them in producing infringing articles. Obviously, if the articles thus produced do not infringe the patent, then any question of contributory infringement falls away. In the court a quo the appellants, individually, denied ‘making, . . . disposing of or offering to dispose of . . . the invention’.8 Their case was that the final product on which Sunsmart relied for its case on infringement, was a combination of various items independently supplied by various dealers. What was common cause, however, was that the flag which is depicted in the photograph, Annexure 'A' to this judgment , and which bears the caption ‘New Heights 1408 CC’ is an example of what can be produced by this combination. For the purpose of discussing the issue of infringement, I shall refer to this article as ‘the New Heights flag’.

[19] In the court a quo Claassen J expressly recorded that it was common cause that the integers of claim 1 of the patent were:

(a) a flag construction comprising

(b) a pole

(i) which includes at least at the top end thereof a flexible section;

(ii) which is adapted to be bent into a substantially U-shaped section; and

(iii) being adapted to engage at least a portion of the upper periphery of a piece of material; and

(iv) to maintain it (i.e. the material) under tension at least in the area defined by the pole, the U-shaped section and a line between a point towards the tip of the flexible section and a point along the length of the pole.

[20] The debate in the court a quo was confined to the question of whether the New Heights flag incorporated integers (b)(iii) and (b)(iv). On appeal before us, however, counsel for the appellants submitted that a drastically different approach to the analysis of the integers in claim 1 should be adopted. His contention was that claim 1 sought protection for a pole with certain characteristics and not for a pole in conjunction with anything else (to quote counsel's heads of argument) ‘more especially any material’.9 There is no substance in this contention. The patent has already been considered by seven judges, none of whom were asked to find that claim 1 related to a pole without the material. Nor, at this late stage of the proceedings, is it necessary for me to say any more than that the experienced flag maker, reading the specification and claims, could not possibly be under the impression that the main claim described a pole stripped of the material with which it must be coupled to comprise a ‘flag construction’.10

[21] Counsel for the appellants repeated the contention that integer (b)(iii) was missing in the New Heights flag. The basis for it was the earlier finding by Southwood J in the Flag and Flagpole case that integer (b)(iii) defined a pole which was adapted (in the sense of ‘being made suitable’ or ‘altered so as to fit’) to engage (in the sense of ‘to fasten or attach’) the material. He decided that no part of the pole in the allegedly infringing article had been made suitable for fastening or attaching the material to it. ‘On the contrary,’ he stated, ‘it is the material which has been adapted to engage the pole. The addition of the sleeve makes this possible.’

[22] Claassen J declined to follow the reasoning of Southwood J in regard to this issue. He took the view that the word ‘engage’ had been used in the sense of requiring the pole to be able to conform to the shape of the upper periphery of the material. There is much to be said for this construction, more especially when one has regard to the circumstance that the word ‘engage’ has a special technical meaning of ‘to interlock with or to fit into a corresponding part’.11 This issue was, however, conclusively resolved by the judgment of this court in para [13] of the Flag and Flagpole case where it was held that, on a proper interpretation of claim 1, the essential requirement is that the pole and the material must be attached to each other, the precise manner in which the attachment is achieved not being material. Streicher JA went on to point out (at para [14]) that claim 4, which is an embodiment of claim 1, defines a specific method by which the material is adapted to house the flexible pole. To construe claim 1 as essentially requiring some mechanism of attachment to be incorporated in the pole, as opposed to the material or to both, would be inconsistent with claim 4. This would be contrary to the ‘normal rule’ of interpretation of claims referred to in the judgment of Trollip JA in Netlon Ltd and Another v Pacnet (Pty) Ltd 1977 (3) SA 840 (A) at 857 G–H, and applied by the learned judge at 857H-858B.

[23] Claassen J, in the court a quo, confined his consideration of whether the New Heights flag incorporated integer (b)(iv) to the simple statement that:

‘As far as (b)(iv) is concerned, it is present in the infringing flag. For all intents and purposes that is exactly what both flags and poles consist of.’12

On appeal before us, counsel for the appellants did not seriously challenge this finding. Instead, counsel sought to place emphasis on the reference in the patent claims to the ‘U-shaped section’ of the flag for which protection was claimed. In the affidavits in the application, the appellants had contended that the New Heights flag could not be described as having a ‘U-shaped’ upper periphery. In this regard the appellants contended that there was a material difference between the (truncated) ‘spiral’ shape of the upper section of the New Heights flag and the ‘semi-circular’ contour of the flag depicted in the patent as an embodiment of the invention. Perhaps conscious that this contention, standing on its own, could not be justified, counsel expanded it into an argument which ran as follows:

(a) In rejecting the contention (in the Flag and Flagpole case) that the Eastaugh patent was an anticipation of the patent-in-suit, this court had emphasised that the ‘question mark shape’ referred to in the Eastaugh patent could not be equated to the ‘inverted U’ claimed in the patent-in-suit.13

(b) By a sort of 'reverse application' of the time-honoured adage 'that which would infringe if later anticipates if earlier’, the corollary to the finding referred to in (a) would be that the article described in the Eastaugh patent would not infringe the patent-in-suit because the shape of its upper periphery would be different to that claimed in the patent-in-suit.

(c) Since there is, likewise, a material difference in the shape of the New Heights flag compared to the article claimed in claim 1 (which, I need hardly stress, is not confined to the embodiment depicted in the drawing), there cannot be an infringement.

[24] The submission is flawed on two fronts. In the first place, it ignores the fact that claim 1 refers to the pole being bent into a ‘substantially U-shaped section’. The skilled addressee would, in my view, appreciate that the ultimate shape of the taut upper periphery of the flag, given that the pole and material are required to engage each other, would ultimately be dictated by the arc taken up by the flexed pole and the shape of the periphery of the material.14 He would surely not construe the claim as being confined to an article in which the combination of the flexed pole and its attachment to the flag material produced an inverted U.15 In the second place the rejection, in the Flag and Flagpole judgment, of the contention that the Eastaugh patent anticipated the patent-in-suit should not be taken to have been confined only to the consideration that the ‘question mark shape’ described in Eastaugh could not be equated to the ‘substantially U-shaped section’ of the patent-in-suit. It is apparent, both from a reading of the description in the body of the Eastaugh patent and from a consideration of the drawings embodying what had been described in words in that specification, that a wide range of resultant shapes was contemplated. It is trite that, in considering whether an earlier document ‘describes’ a later claim, ‘the wider or more general the language (of the earlier document), the less likely it is to render the specific invented process (claimed in the later patent) identifiable and perceptible and therefore to "describe" it.’16 The article contemplated as a part of the invention in the Eastaugh patent is generally described as having a ‘curvilinear edge’ which term plainly embraces a wide range of curved shapes. Accordingly, the finding that the Eastaugh patent did not anticipate the patent-in-suit does not, as a matter of logic, have the necessary result that a spiral-shaped upper section cannot fall within the ambit of the expression ‘substantially U-shaped’.

[25] The appellants' final contention as to why the New Heights flag does not incorporate all of the essential integers of the flag described in the claims, relates to the nature of the pole used in the New Heights flag. As can be seen from the photograph, annexure A, the pole effectively comprises three sections. The lowest of these (which, according to the evidence, is attached to the base support) is a hollow tube which has a diameter larger than the middle section. This middle section is inserted into the lower section, allowing the upper portion of the flag to rotate independently of the lower section. At the top of the middle section there is a gooseneck joint. A solid, flexible baton is inserted into the offset section of the gooseneck and this baton is threaded into the edge pocket sewn into the upper periphery of the flag material. The appellants contended, first, that the pole contemplated by the claims in the patent was a single unit. Accordingly, so the contention ran, the base support and the three-component, rotatably-mounted flag pole used in the New Heights flag were materially different to the pole claimed in the invention. Secondly, they contended that the gooseneck and the baton were materially different to the corresponding integers of the patent claims.

[26] It is plain from a consideration of claim 3, read with the claims preceding it, that claim 1 is not confined to what counsel referred to as a ‘unitary pole’. Claim 2 can only be construed as referring to a pole with at least two constituents - a non-flexible base and a tapered, flexible, fibreglass top. Moreover, claim 3 contemplates a pole in which the tapered section is ‘integral with the pole’. The necessary implication is that claim 1 includes, within its scope, a multi-component pole. Nor (insofar as the appellants' second contention is concerned) are there any stipulations in the patent as to how the components of the pole are to be joined to each other. The situation in this regard is much the same as that relating to the means of attachment of the pole to the flag material. It is apparent that the method of joining the sections of a multi-component pole to one another would not be regarded by the skilled addressee as an essential element of making the flag according to the invention. Such addressee would understand that any form of joint could be used provided that the resultant pole has the attributes required by the claims. In the result, the appellants' contentions that the New Heights flag is not an infringement of the patent all fall to be rejected. I shall deal with the issues relating to contributory infringement after considering the issues of the validity and infringement of the registered design.

Validity of the Design.

[27] In the Flag and Flagpole case, various prior art documents were relied upon in support of the assertion that the design was not new. Southwood J had held that the design was anticipated by one of the drawings in the Rehbein patent and had found it unnecessary to deal with the other alleged anticipations. As already indicated, this court reversed the finding that the Rehbein patent constituted an anticipation.17 The appellants have restricted their attack on the validity of the design to the drawing in the Rehbein patent. The issue has thus already been disposed of by the judgment in the Flag and Flagpole case, and I have nothing to add.

Infringement of the Design.

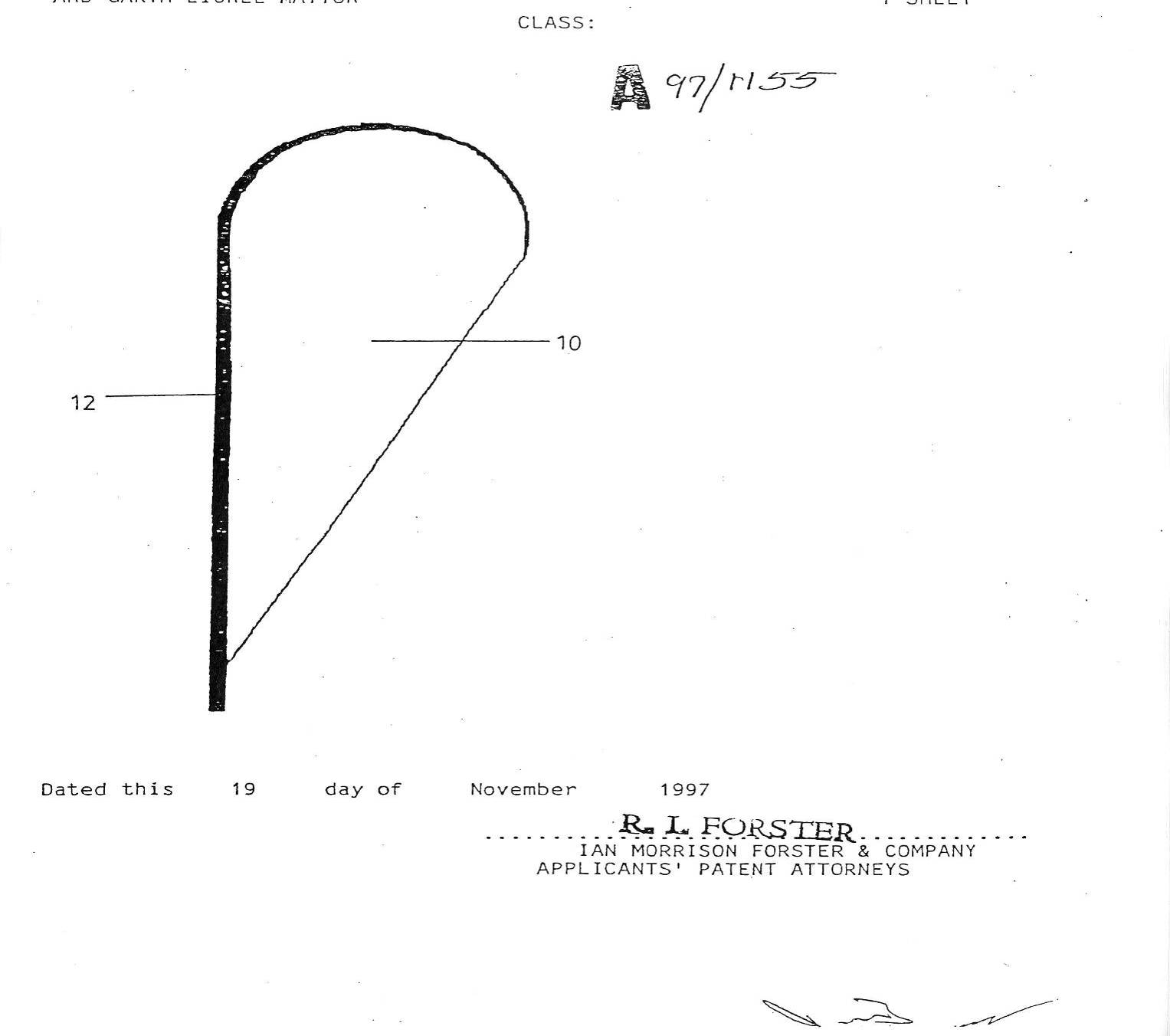

[28] The design was registered as an aesthetic design in part A of the register. The definitive statement reads:

‘The novelty of the design as applied to a flag, banner or the like lies in the shape and/or configuration thereof, substantially as shown in the accompanying drawing.’

The drawing to which reference is made is reproduced in annexure B to this judgment. The explanatory statement reads:

‘A flag or banner is shaped substantially like an inverted teardrop (10) and is adapted to be engaged by a flexible pole (12).’

The appellants contended (unsuccessfully) in the court a quo, and have repeated their contention in argument before us, that there are significant differences between the shape of the New Heights flag and the shape depicted in annexure B. They emphasise (a) the difference in the shape of the curved upper periphery of the design compared with that of the New Heights flag; and (b) the ‘multi-components with their peculiar inter-action’ (I quote from the appellants' heads of argument) of the New Heights flag. The difference alleged in (b) can be disposed of without more ado. Functional features such as the multi-component flagpole and the gooseneck joint in the New Heights flag are not relevant in assessing differences between the New Heights flag and the aesthetic design for which protection is claimed.18 The significance of the difference between the two contours alleged in (a), must be gauged through the eye of the ‘likely customer’.19 Although there is no specific evidence in this regard, I think that it is fair to assume that a very large proportion of the customers in this instance will be attracted to the teardrop shape of the flag, which is plainly a striking feature of the registered design. Comparing the shape of the design with that of the New Heights flag, through the eyes of a hypothetical customer, I do not consider that the subtle differences in curvature of the upper periphery of the two flags would be regarded as significant. It follows that the New Heights flag is an infringement of the registered design.

Contributory Infringement

[29] As indicated earlier the issue of whether the appellants had collaborated to assist each other in conduct which constituted infringement of the patent was referred, in the court a quo, for the hearing of oral evidence. The evidence related to the proceedings in both the patent and the design applications. The particular issues were defined as follow:

'1.1 Whether the first and third respondents were either themselves engaged in the infringing activities as alleged in the papers in the application or were inducing, procuring, aiding or abetting others to infringe;

1.2 Whether the second, fourth and fifth respondents (were) inciting or procuring the first and third respondents to infringe the rights of the applicant as alleged in the papers in the application . . . . '20

[30] Sunsmart called three witnesses, a person (‘Harrison’) who had dealt with Munro in connection with the purchase of the New Heights flag, a person (‘Van der Walt’) who had negotiated with Munro for the supply of teardrop-shaped flags, and the managing director of Sunsmart, Mr Bailey. Only Munro was called as a witness for Vari-Deals and Zimstone. Fritz was not called to give evidence. Claassen J analysed the evidence comprehensively in his judgment. He made explicit findings as to credibility, accepting the evidence of the three witnesses called by Sunsmart, but describing Munro as a 'very poor' witness.21 The appellants' counsel did not suggest that these credibility findings should be interfered with on appeal, and, accordingly, the facts on which the question of contributory infringement falls to be decided can be briefly stated as follow.

[31] At the material times, the sole shareholder and director of Vari-Deals was the erstwhile second appellant, Dr Drake. However, she did not play an active, executive role in the conduct of Vari-Deals' business. That role was filled by Munro who was a 50 percent shareholder, a director and an employee of Zimstone. Zimstone had been appointed as the manager of Vari-Deals' business, so that Munro was de facto in charge of the conduct of business by Vari-Deals. Munro's co-shareholder and co-director in Zimstone was Fritz. In terms of a trade agreement between Vari-Deals and Zimstone, the latter supplied Vari-Deals with various types of poles (including flexible fibreglass poles), gooseneck connectors and pegs. Insofar as the actual management and conduct of Vari-Deals' business was concerned, Munro was actively assisted by Fritz. A copy of the sales brochure emanating from Vari-Deals was annexed to the founding affidavits of Bailey. In it, 'kits' for a teardrop-shaped flag were offered for sale. The kit comprised a set of pole sections, a base and a gooseneck joint. The last two paragraphs of this brochure read as follow:

'CLOTH

Different fabrics perform different functions, and Vari-Deals has sourced a variety of fabrics to ensure the client receives the correct material for a particular requirement. Vari-Deals will point customers in the direction of the appropriate fabric supplier, so that fabric is purchased at the manufacturers' factory prices. Vari-Deals has pre-organised these arrangements.22

CLOTH TAUTNESS

Many competitive products suffer from having cloth tensioned incorrectly, which creates the difference between a spectacular and a shoddy-looking unit. The Vari-Deals Teardrop looks spectacular as it has just the right degree of tension which is created by the combination of a flexible baton and fabric with the correct stretch characteristics.’

[32] The New Heights flag came into existence as a result of an enquiry by Harrison. It was not in dispute that this enquiry was a ‘trap’, Harrison being an employee of Sunsmart. He telephoned Vari-Deals and was put through to Munro. He told Munro he was looking for a flag to advertise CC of which he and his sister were members. Munro stated that Vari-Deals could supply him with a flag and sent at template to him by e-mail with a request that he indicate what 'art-work' he required on the flag. Harrison duly complied with this request. He was told that he should pay the company that did the printing on the flag separately, but that he should pay Vari-Deals the balance of the price which was for the ‘hardware’ and the sewing services. Two complete flag kits (including the printed fabric) were delivered to him under waybills from Zimstone. He received an invoice from Vari-Deals but he made his cheque for the invoiced amount payable to Zimstone. It is important to note that nothing Munro did in relation to this transaction substantiated his later contention that: (a) Vari-Deals acted separately from Zimstone; and (b) Zimstone and Vari-Deals sold only 'pole kits', and not actual flags. There can be no doubt that the transaction with Harrison constituted 'direct infringement' of Sunsmart's patent and registered design.

[33] The evidence of Van der Walt was to the effect that he was in business, selling advertising equipment including flags. He had previously purchased flags from Sunsmart. He had also purchased hardware and banners from Zimstone. In March 2004, he had a conversation with Munro, who informed him that he was producing a new product. (Van der Walt was under the impression that Zimstone would be the actual marketer.) When he heard that the new product was a teardrop-shaped flag (and because the Sunsmart flag was generally known in the trade as a 'teardrop'), Van der Walt informed Munro that the Sunsmart product was the object of patent protection. According to Van der Walt, Munro's response was to the effect that he (or his companies) could 'get round'23 the patent protection. It must be noted that, as cross-examination proceeded, Van der Walt became somewhat equivocal as to the precise words which Munro may have used in response to his warning. In the end he conceded that Munro might have said that the Zimstone/Vari-Deals product 'did not infringe the patent' or 'was different to the patented article'. Claassen J did not deal in his judgment with this equivocal aspect of Van der Walt's evidence. He accepted that Munro told Van der Walt that 'they have ways of getting by it'. Whether this finding is in accordance with the evidence or not is immaterial to the outcome of the appeal. Claassen J correctly treated, as more important than the statement allegedly made by Munro to Van der Walt, the fact (which was not in dispute) that Munro declined to show Van der Walt a sample of his product, saying that he could not do so because of unspecified 'complications'. When pressed to explain what the complications were, Munro gave an answer which Claassen J treated with the appropriate amount of scorn and skepticism. I can do no better than quote the relevant passage from his judgment:

'When asked in court what the complications were, Munro said "the complications were that he (sc Van der Walt) was not very forthcoming during his conversation . . . . He was telling me how wonderful the applicant's product was and I said we did not want to go in and have him as a customer if he saw how wonderful the other product was." This was a very strange answer for a man who wants to sell his product in competition with another product.'

[34] On appeal before us, counsel for the appellants suggested that the affidavit evidence read with the oral evidence established that the appellants had bona fide believed that because they had registered their own patent and design, they did not have the requisite unlawful intent to constitute contributory infringement on their part. In his judgment, Claassen J specifically mentioned that awareness of unlawfulness was one of the essential elements of contributory infringement. This was no doubt based on the dictum in Viskasie Corp v Columbit (Pty) Ltd and Another 1986 BP 432 (CP) at 452E. There has been considerable development of the law relating to contributory infringement in foreign jurisdictions since 1986, generated particularly by the computer age.24 It may well be that the principles of liability for this type of infringement may have to be reconsidered in the light of these developments. However, on the basis of the findings of fact by Claassen J and the inferences which he drew from those findings, it is not necessary to decide the issue of contributory infringement in this case. The contention that the appellants had acted bona fide plainly fell to be rejected, and Claassen J's decision to do so was founded on sound reasons. First, there was the palpable lack of candour in Munro's evidence. Second, the most reasonable and probable inference25 from the evidence concerning his dealings with Van der Walt must be that he knew (or suspected) that if the assembled product was shown to Van der Walt, it might generate an action by Sunsmart for infringement. Thirdly, for some reason, when asked what was different about the appellants' product, Munro kept harping on the 'gooseneck patent' and avoided coming to grips with the question of why he suggested that the appellants' product was not an infringement of Sunsmart's patent and design. The court a quo, having rejected his evidence, clearly drew the correct inference that his conduct was tainted by dolus. Given all the circumstances, I am satisfied that this inference was correctly drawn. Moreover, the failure by Fritz to take the witness stand when it was common cause that he was intimately involved with the conduct of the businesses of Vari-Deals and Zimstone, and closely associated with the Munro in them, also justified the inference that he could not have furthered the appellants' contention that they acted bona fide. He made no effort to contend that he did not know what Munro was about in relation to the 'new product' and it is inconceivable that he (especially with his professed expert knowledge in the field) could not have known that the new product would be an infringement of Sunsmart's patent and design. The evidence and the inferences which can fairly be drawn from it plainly establish that both Vari-Deals and Zimstone, together with their managers/directors, embarked upon a concerted course of action to infringe the patent and the design. In these circumstances the issue of whether there was 'contributory infringement' by Vari-Deals, Zimstone, Fritz or Munro does not arise for decision. Sunsmart discharged the onus of establishing 'direct infringement' by all of them.

[35] In the result, the appeal must be dismissed. I have indicated, at various places in this judgment, that there were errors in the order granted by Claassen J and the following order incorporates the necessary modifications to the order in the court a quo. The amendments thus incorporated do not have any effect on the question of the costs of the appeal. This order is made in respect of both cases in the court a quo, ie High Court case no 21061/2004 and Patent case no 97/10535:

1. The appeal is dismissed.

2. The order of the court a quo is amended to read as follows and an order in the amended form is granted:

'(a) The First, Third, Fourth and Fifth Respondents ('the Respondents') are interdicted and restrained from infringing SA Patent no 97/10535 and SA Design Registration A97/1155;

(b). The Respondents are interdicted and restrained from procuring, inducing, aiding, abetting, advising, inciting, instigating and/or assisting any act of infringement by end users of infringing flags covered by the said patent and/or the said design;

(c) The Respondents are ordered to deliver up to the Applicant for destruction all infringing flags in their possession or under their control.

(d) The Respondents are ordered to pay the costs of the application under case no 21061/2004 and Patent case no 97/10535.

(e) The Applicant is ordered to pay the costs of the Sixth and Seventh Respondents up to and including the date of filing of their opposing papers in each of the applications referred to in para (d) hereof.'

3. The first, third, fourth and fifth appellants are ordered to pay the respondent's costs of appeal, such costs to include the costs consequent upon the employment of two counsel.

………………………

N V HURT AJA

CONCUR:

HARMS ADP

NUGENT JA

PONNAN JA

COMBRINCK JA

ANNEXURE A

ANNEXURE B

1Sunsmart v Flag and Flagpole Industries [2007] SCA 50 (RSA).

2Catholic Bishops Publishing Co v State President and Ano 1990 (1) SA 849(A) at 866; Brisley v Drotsky 2002 (4) SA 1 (SCA) at paras 55-60.

3 As to which see Catnic Components Ltd and Ano v Hill and Smith Ltd [1982] RPC (HL); Improver Corporation and Others v Remington Consumer Products Ltd and Others [1970] FSR 181.

4 As crystallized in Gentiruco AG v Firestone (Pty) Ltd 1972 (1) SA 589 (A) at 613-618, and modified in such cases as Multotec Manufacturing (Pty) Ltd v Screenex Wire Weaving Mnfrs (Pty) Ltd 1983 (1) SA 709 (A) and Sappi Fine Papers (Pty) Ltd v ICI Canada Inc 1992 (3) SA 306 (A).

5 L T C Harms, The Enforcement of Intellectual Property Rights: A Case Book, p 188-198.

6 In Kirin-Amgen Inc and Ors v Hoechst Marion Rousel and Ors [2005] 1 All ER 667, Lord Hoffman sketched the history of the reception of the concept of ‘purposive interpretation’ in English Law. In para [33] (at p 680) he said : 'Construction, whether of a patent or any other document, is of course not directly concerned with what the author meant to say. There is no window into the mind of the patentee or the author . . . Construction is objective in the sense that it is concerned with what a reasonable person to whom the utterance was addressed would have understood the author to be using the words to mean. . . . . . The meaning of words is a matter of convention, governed by rules, which can be found in dictionaries and grammars. What the author would have been understood to mean by using those words is not simply a matter of rules. It is highly sensitive to the context of and background to the particular utterance.’

7 In addition, counsel was unable to identify the presence of integer (b)(iv), referred to in para 19 below, in the Eastaugh patent.

8 Section 45 of the Patents Act.

9 This contention was adumbrated in para 31 of the answering affidavit of Fritz [pp 151-152], but apparently not persisted in before Claassen J.

10 The definition of a ‘flag’ in the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, 3 ed, p 708 (assuming that the addressee of the patent, bemused by the appellant's contention, might have been driven to look this word up) is given as ‘A piece of stuff . . . . usually oblong or square, attached by one edge to a staff, used . . . for display.’

11 Oxford English Dictionary (2 ed) Volume V, p 247.

12 Southwood J had also held that integer (b)(iv) was incorporated in the allegedly infringing article in the Flag and Flagpole case, the construction of which, in this particular aspect, was, for all practical purposes, identical to that of the New Heights flag. His finding on this aspect was expressly approved by Streicher JA in para [19].

13Flag and Flagpole judgment, paras [26] and [27].

14 This much was expressly stated by Fritz in para 24 of his answering affidavit. [p149]

15 Cf the finding of the court in Catnic, where the word ‘vertical’ was was interpreted to mean ‘approximately vertical’.

16Gentiruco at 649G.

17 Streicher JA's judgment, para 37.

18 Section 1(1)(i) of the Designs Act defines an aesthetic design as ‘any design applied to any article, whether for the pattern or the shape or the configuration or the ornamentation thereof, or for any two or more of those purposes, and by whatever means it is applied, having features which appeal to and are judged solely by the eye, irrespective of the aesthetic quality thereof’.

19Homecraft Steel Industries (Pty) Ltd v S M Hare and Son (Pty) Ltd 1984 (3) SA 681 (A) at 692 B-D.

20 It will be recalled that in the application proceedings in the court a quo the first respondent was Vari-Deals, the third respondent was Zimstone, the fourth respondent was Munro and the fifth respondent was Fritz. The proceedings against the second respondent were later withdrawn.

21 The learned judge elaborated on this finding by stating that '(Munro) was evasive, off the point, constantly referring back to the gooseneck patent when it had nothing to do with the real issue. He contradicted himself several times, e.g. at one stage he admitted he acted as a facilitator for Harrison but later denied it and tried to escape from the obvious inference thereof by saying he only made recommendations to Harrison. Although his brochure says that the cloth for the banners is pre-arranged by him, he denied in evidence that that is done at all’.

22 My emphasis.

23‘omseil’.

24 See, eg, Sony Corp of America v Universal Studios, Inc 464 US 417; Metro-Goldwyn-Mayo Studios Inc v Grokster Ltd (04-480) 380 F 3d 1154, at pp12-19.

25 Govan v Skidmore 1952 (1) SA 732 (N) at p 34 C–D.