THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEAL

OF SOUTH AFRICA

Case No 125/06

Reportable

In the matter between:

CLIPSAL AUSTRALIA (PTY) LTD 1st Appellant

CLIPSAL SOUTH AFRICA (PTY) LTD 2nd Appellant

and

TRUST ELECTRICAL WHOLESALERS 1st Respondent

GAP DISTRIBUTOR 2nd Respondent

Coram: HARMS ADP, STREICHER, CLOETE, LEWIS AND CACHALIA JJA

Heard: 27 FEBRUARY 2007

Delivered: 23 MARCH 2007

Summary: Designs Act 195 of 1993 – novelty – originality – infringement.

Neutral Citation: Clipsal Australia (Pty) Ltd v Trust Electrical Wholesalers [2007] SCA 24 (RSA).

J U D G M E N T

HARMS ADP/

HARMS ADP:

[1] The proprietor of a registered design and the local exclusive licensee (the appellants) sought relief against the respondents on the ground that they are infringing their design registration. Blieden J, in the high court, dismissed the application with costs on the ground that the design had not been validly registered because it was not new or original; he also held that the design in any event had not been infringed. He granted the necessary leave to appeal.

[2] The design (A 96/0687) was registered under the Designs Act 195 of 1993 as an aesthetic design in class 13, which covers equipment for the production, distribution or transformation of electricity. The Act draws a distinction between aesthetic and functional designs. The definition of the former reads (s 1(1)):

‘“aesthetic design” means any design applied to any article, whether for the pattern or the shape or the configuration or the ornamentation thereof, or for any two or more of those purposes, and by whatever means it is applied, having features which appeal to and are judged solely by the eye, irrespective of the aesthetic quality thereof.’

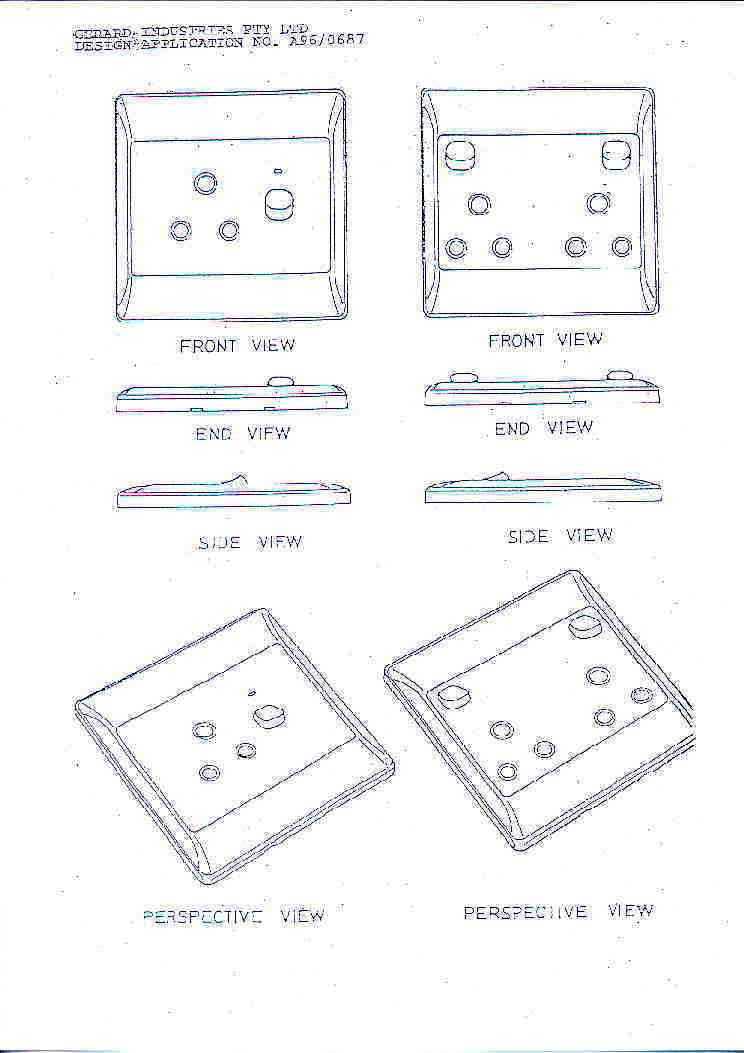

[3] The articles to which the design registration applies are ‘a set of electrical accessory plates with surrounds’. According to the definitive statement protection is claimed for ‘the features of shape and/or configuration of a set of electrical accessory plates with surrounds as shown in the accompanying drawings’. The drawings, which are an annexure to this judgment, show two configurations, hence the reference to a ‘set’ in both the title and the definitive statement. The one configuration is for what is normally known as a cover plate for a single wall socket for a three-prong electric plug with switch and the other is a cover plate for a double socket with two switches. These cover plates are rectangular. They are both surrounded by a square plate which has a slightly convex slope. Because of the relative shape of the rectangular cover plate and the square surround only the opposite sides of the surround are of the same width.

[4] The effect of the registration of a design is to grant to the registered proprietor the right to exclude others from the making, importing, using or disposing of any article included in the class in which the design is registered and embodying the registered design or a design not substantially different from the registered design (s 20(1)).

[5] The defendant in infringement proceedings may counterclaim for the revocation of the design registration or, by way of defence, rely on any ground on which the registration may be revoked (s 35(5)). In this case the respondents chose the second option, namely to rely by way of defence on the grounds that the design was neither new nor original as required by s 14(1)(a), which are grounds for revocation under s 31(1)(c). In addition they denied infringement, alleging that their products do not embody either of the two designs and differ substantially from them.

[6] The respondents are making and marketing electrical accessory plates with surrounds under the name Lear G-2000 series single electrical socket SYZ – 16 (100 x 100) and double electrical socket S2YZ2 – 16 (100 x 100). These fall in the same class as the protected designs, which means that the first issue to determine is the scope of the design registration, which in turn requires a construction of the definitive statement and the drawings.1 The purpose of the definitive statement, previously known as a statement of novelty, is to set out the features of the design for which protection is claimed and is used to interpret the scope of the protection afforded by the design registration.2

[7] The definitive statement in this case is of the omnibus type because it does not isolate any aspect of the design with the object of claiming novelty or originality in respect of any particular feature. As Laddie J explained in Ocular Sciences Ltd v. Aspect Vision Care Ltd [1997] RPC 289 at 422:

‘The proprietor can choose to assert design right in the whole or any part of his product. If the right is said to reside in the design of a teapot, this can mean that it resides in design of the whole pot, or in a part such as the spout, the handle or the lid, or, indeed, in a part of the lid. This means that the proprietor can trim his design right claim to most closely match what he believes the defendant to have taken.’

This means that the shape or configuration as a whole has to be considered, not only for purposes of novelty and originality, but also in relation to infringement.3

[8] Important aspects to consider when determining the scope of the registered design protection flow from the definition of an ‘aesthetic design’, namely that design features have to appeal to and be judged solely by the eye. First, although the court is the ultimate arbiter, it must consider how the design in question will appeal to and be judged visually by the likely customer.4 Secondly, this visual criterion is used to determine whether a design meets the requirements of the Act and in deciding questions of novelty and infringement.5 And thirdly, one is concerned with those features of a design that ‘will or may influence choice or selection’ and because they have some ‘individual characteristic’ are ‘calculated to attract the attention of the beholder.’6 To this may be added the statement by Lord Pearson that there must be something ‘special, peculiar, distinctive, significant or striking’ about the appearance that catches the eye and in this sense appeals to the eye.7

[9] The respondents sought to rely on the fact that a ‘set’ of articles was registered by arguing that the relevant features to be considered in determining the scope of the protection are those that are common to all members of a set. A ‘set of articles’ is a number of articles of the same general character which are ordinarily on sale together or intended to be used together, and in respect of which the same design, or the same design with modifications or variations not sufficient to alter the character of the articles or substantially affect their identity, is applied to each separate article (s 1(3)). Any question as to whether a number of articles constitute a set has to be determined by the registrar (s 1(4)). The object of the provision is to enable an applicant to obtain registration for the design of more than one article for the price of one.8 If the Registrar has registered articles as a set when they in truth do not form a set it is at best a matter for review but it cannot be raised as a defence to infringement or be a ground for revocation.9 Can the registration as a set then be a method of interpreting the scope of the registration? I think not. This follows not only from the purpose of the provision relating to sets but also from other definitions and especially s 1(2). A design has to apply to an ‘article’ which includes any article of manufacture and a reference to an article is deemed to be a reference to (a) a set of articles; (b) each article which forms part of the set of articles; or (c) both a set of articles and each article which forms part of that set. This can only mean that each member of a set has its own individuality and must be assessed on its own and that the exercise which we were asked to undertake is not permissible.

[10] Against that background I turn to determine those features of the two designs that appeal to the eye and are to be judged solely by the eye. There is no direct evidence about who the likely customers are (whether architects, builders, electricians or homeowners) or how the likely customer would view them but there is the evidence of the managing director of the exclusive licensee, Mr Evans, and that of a director of the second respondent, Mr Botbol, who are both experienced in this field, and their evidence defined the issues in the case (the affidavits performing in these proceedings the function of pleadings and evidence).

[11] Mr Evans alleged that the dominant aesthetic feature of the design resides in the shape and configuration of the ‘substantially square’ surround and the rectangle contained therein, and the shape and configuration of the socket holes and their associated switches, relative to the rectangle. He added that the secondary and further aesthetic features are the slope of the square surround at the top and bottom and on the left and right-hand sides and the annular recesses surrounding the socket holes. Mr Botbol’s response was not enlightening. He did not deny any of these allegations, especially not those about the relative value of the different features. He added though that curvature of the square surrounds is convex.

[12] As mentioned, the high court held that the design was not new. In coming to this conclusion the court had regard to eight prior art documents, each showing ‘that various elements of the registered socket (sic!) were all previously part of the art.’ The court added that the registered ‘sockets’ show nothing ‘novel or original’ and that they are no more than an ordinary trade variant of similar products.

[13] Over the objection of the appellants the high court held that it was entitled to mosaic different pieces of prior art. This is a surprising conclusion. It is old law that one is not entitled to mosaic for purposes of novelty.10 This principle is also well established in patent law and as Pollock B had said more than a century ago, the Designs Act was intended to add to the Patent Act by making that which was not patentable the subject of a design.11 There is nothing in the Act to justify a departure from this principle especially since obviousness is not a ground of invalidity of a design. A design is not novel if it forms part of the prior art – meaning that it is to be found in the prior art – and not if it can be patched together out of the prior art.

[14] This does not mean that absolute identity has to be shown; only substantial identity is required. Immaterial additions or omissions are to be disregarded, so, too, functional additions or omissions.12 That is why it is usually said that an ordinary trade variant is not sufficient to impart novelty. This principle is well illustrated by the facts in Schultz v Butt.13 The design in issue related to a boat and differed from a previous design by the addition of what was assumed to be a novel and original window structure. This addition did not make the claimed design new. Basically its function was to protect the occupants against spray and wind and since it was an ordinary trade variant and since the design as a whole was not substantially novel, the design was held to be invalid.14

[15] That brings me to the second finding of the high court, namely that the design is merely a trade variant of similar products. The problem is, however, that the court did not identify the similar products. The first document relied upon by the respondents to destroy novelty shows a square cover plate for a single socket with a rectangular hole for a switch. The second is also a square cover plate but the switch has two press points. The third is similar to the first except that a swivel switch is shown. The fourth is simply the double socket variety of the first. The fifth consists of what the present registration certificate calls a surround but it is rectangular, the sides are at a 90 degree angle and they all have the same width. The next one is for a single switch assembly with no socket holes and the form of the switch is the same as that shown in the drawings, which is not unexpected in view of the fact that the applicant for that registration is the present proprietor’s predecessor in title. There is also one showing the same type of switch but as a double switch.

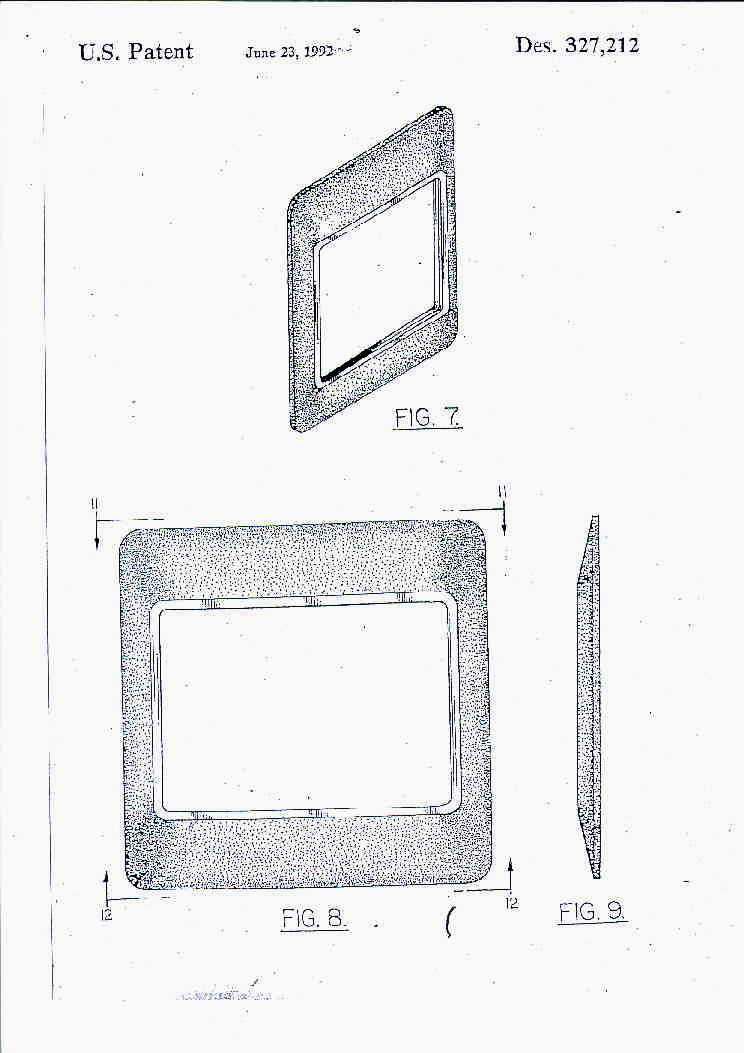

[16] In conclusion there is US Patent 327 212 which relates to an ornamental design for a wall plate for an electric wiring device, in other words, for a surround. It has two embodiments of which the second is material and is reproduced as an annexure to this judgment. It shows a surround that is substantially identical to the surround in the drawings because the outer perimeter is square whereas the inner boundary (where a covering plate could be placed) is rectangular and the sides are all convex, sloping from the inner border to the outer border. The argument for the respondents is that this document discloses the design in issue because it permits one to place any socket design within the surround. Although attractive at first blush, the argument has to fail because it means that the more general a prior disclosure is, the easier it anticipates, whereas the opposite is true: the more general the disclosure the less likely it renders the particular design identifiable.15 There is another aspect and that is that the inner border of this surround has a clearly defined frame, something lacking in the registered design which leads to the consideration of another test: that which infringes if later, anticipates if earlier.16 I find it difficult to envisage that this design could be said to be to be an infringement of the registered design in issue.

[17] I therefore conclude that the high court erred in finding that the design lacked novelty. But this exercise was nevertheless important for another reason. The definitive statement and the drawings have to be assessed in the light of the state of the art to determine the degree of novelty achieved. This is so because where the measure of novelty of a design is small the ambit of the ‘monopoly’ is small.17 As Burrell suggests, to consider the definitive statement without regard to the prior art would eviscerate its purpose.18

[18] The high court also held that the design was not original as required by the Act. Originality, it held, requires that the design has to be substantially different from what has gone before, so as to possess some individuality; it has to be special, noticeable, and capture and appeal to the eye. For this the court relied on Malleys Ltd v JW Tomlin (Pty) Ltd (1994) 180 CLR 120, a judgment of the High Court of Australia. The judgment is not authority for the proposition. The main issue was whether the design was altogether too vague to qualify for registration. It was in this context that the court had regard to the factors mentioned, including the individuality of the design and it concluded on the facts that ‘there is sufficient individuality of appearance to justify registration if the design was new or original.’ Another aspect of the judgment that should be noted is that the Australian Act required that a design had to be ‘new or original’ and not (as our Act now reads) that it has to be new and original. Because the court had found that the design was new it did not find it necessary to consider whether it was original (in whatever sense of the word).

[19] Because of the difference in wording and underlying structure of design statutes older and foreign authorities must be read in context.19 The UK Designs Act 1842 spoke of new and original but this was changed to new or original in the UK Patents, Designs and Trade Marks Act 1883.20 It was this latter usage that was taken over in our 1916 Act but what was new or original had to be assessed against prior use, publication, registration, or patenting.21 Our Designs Act 57 of 1967 had a similar provision, which required that a design had to be ‘new or original’ if tested against certain prior art.22 In a similar statutory context Graham J held that the term was disjunctive and that what ‘original’ added was merely that the design had to be substantially novel.23

[20] The current Act of 1993 differs structurally from its antecedents. It requires that a design must be new and original. Only novelty is tested against the defined prior art (‘a design shall be deemed to be new if it is different from or if it does not form part of the state of the art’).24 There is no measure against which originality has to be tested. Before proceeding, it is necessary to recall that this Court in Homecraft,25 following the House of Lords in Amp Inc v Utilux, has held that a design must have, by virtue of the definition, some ‘individual characteristic’ ‘calculated to attract the attention of the beholder’26 and that there must be something ‘special, peculiar, distinctive, significant or striking’ about the appearance that catches the eye and in this sense appeals to the eye.27 These requirements have nothing to do with originality. In fact, neither Amp Inc v Utilux nor Homecraft dealt with originality. It is furthermore incorrect to equate (as the high court did) originality with not being commonplace in the art although that is how the concept is defined in the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. The reason is obvious. The 1993 Act requires that aesthetic designs must be new and original and that functional designs must be new and not commonplace.28 Originality and being ‘not commonplace’, consequently, cannot mean the same. The only other meaning ‘original’ can bear is one that is the same or akin to the meaning in copyright law,29 something that is not farfetched if regard is had to the fact that the 1916 Act spoke of design copyright. As was said by Mummery LJ in Farmers Build v Carier [1999] RPC 461 at 482:30

‘The court must be satisfied that the design for which protection is claimed has not simply been copied (e.g. like a photocopy) from the design of an earlier article. It must not forget that, in the field of design of functional articles, one design may be very similar to or even identical with another design and yet not be a copy: it may be an original and independent shape and configuration coincidentally the same or similar. If, however, the court is satisfied that it has been slavishly copied from an earlier design, it is not an "original" design in the "copyright sense".’

[21] In the light of these considerations I conclude that the respondents’ case on lack of originality as adopted by the high court founders because it is based on an incorrect premise. This then brings me to the question of infringement which involves a determination of whether the respondents’ products embody the registered design or a design not substantially different from the registered design. The search is not for differences but for substantial ones.

[22] This test is not a trade mark infringement test and the issue is not whether or not there is confusion or deception and it would therefore be wrong to introduce concepts developed in a trade mark context such as imperfect recollection into this part of the law. The designs test is closer to the patent infringement test. This dictum from Incandescent Gas Light Co v de Mare etc System31 in a patent infringement context is equally applicable to the present context:

‘When, however, you come to make that comparison, how can you escape from considering the relative magnitude and value of the things taken and of those left or varied; it is seldom that the infringer does the thing, the whole thing, and nothing but the thing claimed by the specification. He always varies, adds, omits and the only protection the patentee has in such a case lies, as has often been pointed out by every Court, from the House of Lords downward, in the good sense of the tribunal which has to decide whether the substance of the invention has been pirated.’

[23] Both the single and double socket articles produced and sold by the respondents have square surrounds with rectangular cover plates. Both incorporate in general terms the registered designs, even down to the annular recesses and the shapes and configuration of the switches. What are the differences? As Mr Evans mentioned, the respondents’ surrounds have stepped slopes on the right and left (the narrow) sides instead of the substantially convex curvature of the registered design.32 Recognising this difference, the next question is whether it is a substantial difference. Mr Evans’s allegation that this particular feature is a secondary feature has not been placed in issue. It is difficult to see how a difference in respect of a secondary feature can be substantial.

[24] The other differences are these. The position of the respondents’ double socket switches is directly above the earth socket hole whereas that of the design is closer to the upper corners of the rectangular plate. Mr Evans said that this difference was not substantial and Mr Botbol did not deny his evaluation. The same applies to the single socket article where the position of the switch is closer to the earth socket hole. There is an additional feature in the single socket design and that is the presence of what appears to be a small hole above the switch. This may be for an indicator light but, in any event, the respondents do not have it. No-one has suggested that its absence makes a substantial difference and I do not think that anyone could have done so seriously.

[25] My evaluation of the prior art shows that the level of novelty of this design is not such that small differences are material. There is against this background another way of determining whether there was infringement and that is to ask whether, if the respondents’ article had been part of the prior art, the design would have been new. The answer must be no because the move of the position of the switches and the removal of the steps on the narrow sides of the surrounds would have been regarded as trade variants. What anticipates if earlier, in general terms, infringes if later, the converse of the general rule mentioned earlier. It follows that the differences, which are per se insubstantial, do not save the respondents from infringing.

[26] The appeal is upheld with costs and the order of the court below replaced with an order –

1. interdicting the respondents from infringing registered design A96/0687 by making, importing, using, or disposing of the Lear G-2000 series single electrical socket SYZ – 16 (100 x 100) and double electrical socket S2YZ2 – 16 (100 x 100);

2. directing the respondents to surrender all infringing articles in their possession to the applicants;

3. directing that an enquiry be held for the purposes of determining the amount of any damages suffered by the applicants or for the determination of a reasonable royalty as contemplated in s 35(3)(d) of the Designs Act 195 of 1993, and ordering payment of such damages found to have been suffered or of such reasonable royalty;

4. directing, in the event of the parties being unable to reach agreement as to the future pleadings to be filed, discovery, inspection or other matters of procedure relating to the enquiry, that any party is authorized to apply for directions in regard thereto;

5. directing the respondents to pay the applicants’ costs.

_________________________

L T C HARMS

ACTING DEPUTY PRESIDENT

AGREE:

HARMS ADP

STREICHER JA

CLOETE JA

LEWIS JA

CACHALIA JA

1 TD Burrell ‘Designs’ 8 Lawsa 2 ed para 257. Further references to Lawsa are to this edition and volume.

2 Design Regulations GNR 844 of 2 July 1999 reg 15(1).

3Schultz v Butt 1986 (3) SA 667 (A) at 686D-G per Nicholas AJA. Jones & Attwood Ltd v National Radiator Co Ltd (1928) 45 RPC 71 at 83 line 5-12.

4Homecraft Steel Industries (Pty) Ltd v SM Hare & Son (Pty) Ltd 1984 (3) SA 681 (A) at 692B-D per Corbett JA. I agree with these comments by Jacob J in Oren and Tiny Love Ltd v. Red Box Toy Factory Ltd [1999] EWHC Patents 255: ‘I do not think, generally speaking, that "expert" evidence of this opinion sort (i.e. as to what ordinary consumers would see) in cases involving registered designs for consumer products is ever likely to be useful. There is a feeling amongst lawyers that one must always have an expert, but this is not so. No-one should feel that their case might be disadvantaged by not having an expert in an area when expert evidence is unnecessary. Evidence of technical or factual matters, as opposed to consumer "eye appeal" may, on the other hand, sometimes have a part to play - that would be to give the court information or understanding which it could not provide itself.’

5Homecraft at 692D.

6 Lord Morris of Borth-Y-Gest in Amp Inc v Utilux (Pty) Ltd 1972 RPC 103 (HL) at 112 quoted with approval in Homecraft at 691D-F.

7Amp Inc v Utilux (Pty) Ltd at 121 quoted with approval in Robinson v D Cooper Corporation of SA (Pty) Ltd 1984 (3) SA 699 (A) at 704G per Corbett JA.

8 Laddie, Prescott and Vitoria The Modern Law of Copyright and Designs 2 ed vol 1 para 30.40.

9 Cf Kimberly-Clark of SA (Pty) Ltd (formerly Carlton Paper of SA (Pty) Ltd) v Proctor & Gamble SA (Pty) Ltd [1998] 3 All SA 77, 1998 (4) SA 1 (A). Also s 32: ‘Registration of a design shall be granted for one design only, but no person may in any proceedings apply for the revocation of such registration on the ground that it comprises more than one design.’

10Jones & Attwood at 82 line 44-49.

11Moody v Tree (1892) 9 RPC 333 at 335.

12Le May v Welch (1884) 28 Ch D 24 at 35; Sebel’s Applications [1959] RPC 12 at 14.

13Schultz v Butt 1986 (3) SA 667 (A).

14Schultz v Butt at 686G-687G.

15 Cf Gentiruco AG v Firestone SA (Pty) Ltd 1972 (1) SA 589 (A) at 648E-G, a patent case under the Patents, Designs, Trade Marks and Copyright Act 9 of 1916.

16 I am aware that this ‘rule’ is usually used in a different context but the underlying principle appears to be applicable. Cincinnati Grinders Inc v BSA Tools Ltd (1931) 48 RPC 33 at 58.

17Homecraft Steel Industries (Pty) Ltd v SM Hare & Son (Pty) Ltd 1984 (3) SA 681 (A) at 695F per Corbett JA.

18Lawsa para 271.

19 Cf Landor & Hawa International Ltd v Azure Designs Ltd [2006] EWCA Civ 1285 para 39.

20Aspro-Nicholas Ltd’s Design Application [1974] RPC 645 at 651.

21 Patents, Designs, Trade Marks and Copyright Act 9 of 1916 s 80(1).

22 Section 4(2): ‘For the purposes of this Act a design shall be deemed to be a new or original design if, on or before the date of application for registration thereof, such design or a design not substantially different therefrom, was not—

(a) used in the Republic;

(b) described in any publication in the Republic;

(c) described in any printed publication anywhere;

(d) registered in the Republic;

(e) the subject of an application for the registration of a design in the Republic or of an application in a convention country for the registration of a design which has subsequently been registered in the Republic in accordance with section 18.’

23Aspro-Nicholas Ltd’s Design Application at 653 lines 6-9.

24 Section 14(2). The state of the art comprises principally all matter which has been made available to the public (whether in the Republic or elsewhere) by written description, by use or in any other way (s 14(3)).

25Homecraft Steel Industries (Pty) Ltd v SM Hare & Son (Pty) Ltd 1984 (3) SA 681 (A).

26 Lord Morris of Borth-Y-Gest in Amp Inc v Utilux (Pty) Ltd 1972 RPC 103 (HL) at 112 quoted with approval in Homecraft at 691D-F.

27Amp Inc v Utilux (Pty) Ltd 1972 RPC 103 (HL) at 121 quoted with approval in Robinson v D Cooper Corporation of SA (Pty) Ltd 1984 (3) SA 699 (A) at 704G per Corbett JA.

28 Section 14(1): ‘The proprietor of a design which—

(a) in the case of an aesthetic design, is—

(i) new; and

(ii) original,

(b) in the case of a functional design, is—

(i) new; and

(ii) not commonplace in the art in question,

may, in the prescribed manner and on payment of the prescribed fee, apply for the registration of such design.’

29 Cf Christine Fellner Industrial Design law (1995) para 2.255 who points out that there may be differences in application.

30 Quoted in Dyson Ltd v Qualtex (UK) Ltd [2006] EWCA Civ 166.

31 13 RPC 301 at 330 and quoted more than once with approval by this Court. See Letraset Ltd v Helios Ltd 1972 (3) SA 245 (A) at 275A-B.

32 The photographic exhibits do not show this and are of a too poor quality to reproduce. It is, however, apparent from the physical exhibits.

Cited documents 2

Judgment 2

Documents citing this one 1

Judgment 1

| 1. | Strix Limited v Nu-World Industries (20453/2014) [2015] ZASCA 126 (22 September 2015) | 3 citations |