THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEAL

OF SOUTH AFRICA

Reportable

Case No: 250/06

In the matter between:

VERIMARK (PTY) LTD

Appellant

and

BAYERISCHE MOTOREN WERKE

AKTIENGESELLSCHAFT Respondent

and in the matter of a cross-appeal between:

BAYERISCHE MOTOREN WERKE

AKTIENGESELLSCHAFT Appellant

and

VERIMARK (PTY) LTD

Respondent

Coram : Harms ADP, Streicher, Cloete, Ponnan and Combrinck JJA

Heard : 2 MAY 2007

Delivered : 17 MAY 2007

Summary: Trade mark infringement – use as a trade mark – unfair advantage of a well-known trade mark.

Neutral Citation: This judgment may be referred to as Verimark (Pty) Ltd v BMW AG [2007] SCA 53 (RSA)

JUDGMENT

HARMS ADP

[1] This case is about trade mark infringement. The well-known BMW logo1 is registered in different classes and those in contention are registered (a) in class 3 for, amongst others, cleaning and polishing preparations and vehicle polishes (the polish mark, TM 1987/05127); and (b) in class 12 for vehicles, automobiles and the like (the car mark, TM 1956/00818/1).

The owner of the mark, the present respondent (Bayerische Motoren Werke AG, in short BMW) applied in the high court under the provisions of s 34(1) of the Trade Marks Act 194 of 19932 for an interdict restraining the respondent (the present appellant, Verimark (Pty) Ltd) from infringing these two trade marks. The court (per de Vos J) found in favour of BMW in relation to its claim based on the polish mark (a) but dismissed the application in relation to its car mark (b).3 This gave rise to an appeal and cross-appeal with the leave of that court.

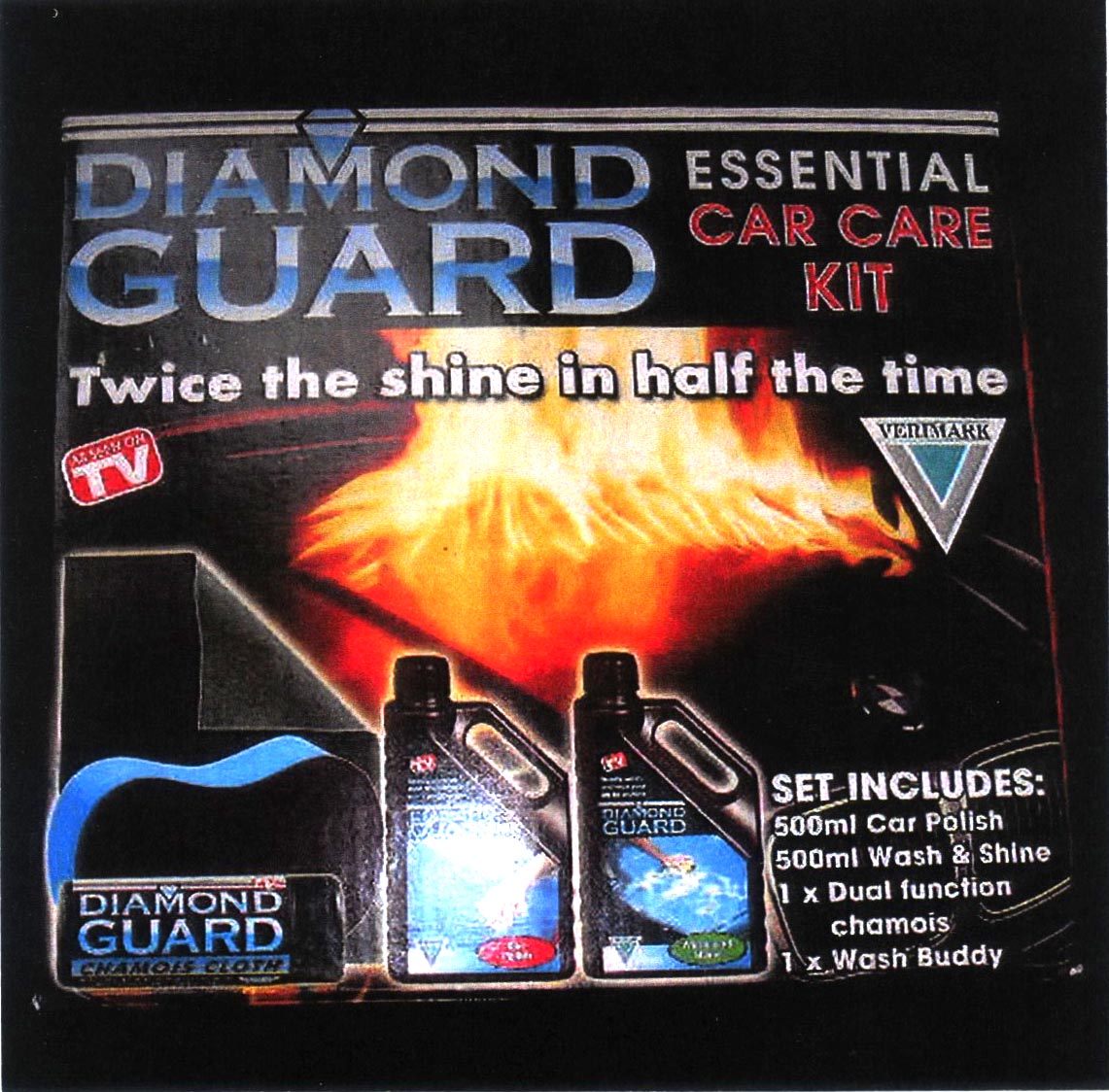

[2] Verimark is the market leader in the field of direct response television marketing in which demonstrative television commercials are used. Two of its many products are its Diamond Guard car care kit and Diamond Guard car polish. These have been widely advertised and sold since 1996. Throughout this period Verimark used vehicles of different makes, but more particularly BMW cars, to demonstrate the wonders of these products. In one particular television flight a BMW car is first treated with Diamond Guard and then an inflammable liquid is poured onto the hood of the car and set alight without causing any damage to the car’s paintwork. In another instance an older and cheaper car is treated with Diamond Guard and it then metamorphoses into a shining BMW. The complaint of BMW is that its logo on the BMW car is clearly visible and because of this its case is that Verimark is infringing its trade mark registrations. The same complaint is directed at the use of a clip from the first flight as background on its packaging material and in its internet advertisement. A representation of the packaging material is annexed to this judgment.

[3] BMW relies on the provisions of s 34(1)(a) for its allegation that its class 3 trade mark for polishes has been infringed. This paragraph provides (to the extent relevant) that the rights acquired by registration of a trade mark are infringed by the unauthorized use of an identical mark in the course of trade in relation to goods in respect of which the trade mark is registered. The argument is simply that the BMW logo appears on the packaging material and in the advertisements; the logo is identical to the registered trade mark; the use by Verimark is not authorised; and it is use in the course of trade in relation to polishes. Therefore there is infringement.

[4] Verimark, on the other hand, argues that ‘use’ in this context must be ‘trade mark use’ meaning

‘use of a registered trade mark for its proper purpose (that is, identifying and guaranteeing the trade origin of the goods to which it is applied) rather than for some other purpose’4

and that its use of the BMW logo does not amount to trade mark use because it is not used as and cannot be perceived to be a badge of origin. It argues that the product is clearly identified as Diamond Guard and nothing else and that the BMW logo identifies the car on which the product is being used and not the polish. In this regard Verimark relies on recent developments in the European Court of Justice (the ECJ) and the English courts5 and on a dictum of this Court in Bergkelder.6 Against this are two high court judgments7 that were based on a literal interpretation of the provision and on the reasoning in British Sugar plc v James Robertson & Sons Ltd [1996] RPC 281 (Ch), which has since been overruled in this regard.

[5] It is trite that a trade mark serves as a badge of origin and that trade mark law does not give copyright-like protection. Section 34(1)(a), which deals with primary infringement and gives in a sense absolute protection, can, therefore, not be interpreted to give greater protection than that which is necessary for attaining the purpose of a trade mark registration, namely protecting the mark as a badge of origin. In Anheuser-Busch8 the ECJ was asked to determine the conditions under which the proprietor of a trade mark has an exclusive right to prevent a third party from using his trade mark without his consent under a primary infringement provision. The ECJ affirmed (at para 59) that

‘the exclusive right conferred by a trade mark was intended to enable the trade mark proprietor to protect his specific interests as proprietor, that is, to ensure that the trade mark can fulfill its functions and that, therefore, the exercise of that right must be reserved to cases in which a third party’s use of the sign affects or is liable to affect the functions of the trade mark, in particular its essential function of guaranteeing to consumers the origin of the goods.’

That is the case, the ECJ said (at para 60), where the use of the mark is such that it creates the impression that there is a ‘material link in trade between the third party’s goods and the undertaking from which those goods originate’. There can only be primary trade mark infringement if it is established that consumers are likely to interpret the mark, as it is used by the third party, as designating or tending to designate the undertaking from which the third party’s goods originate.

[6] As far as English courts are concerned, I do not intend to trawl through the development of the law9 but shall limit myself by referring to some of the observations of the House of Lords in Johnstone.10 Lord Nicholls of Birkenhead stated (at para 13):

‘But the essence of a trade mark has always been that it is a badge of origin. It indicates trade source: a connection in the course of trade between the goods and the proprietor of the mark. That is its function. Hence the exclusive rights granted to the proprietor of a registered trade mark are limited to use of a mark likely to be taken as an indication of trade origin. Use of this character is an essential prerequisite to infringement. Use of a mark in a manner not indicative of trade origin of goods or services does not encroach upon the proprietor's monopoly rights.’

Taking his cue from the ECJ jurisprudence, Lord Walker said (at para 84):

‘The [ECJ]11 has excluded use of a trade mark for "purely descriptive purposes" (and the word "purely" is important) because such use does not affect the interests which the trade mark proprietor is entitled to protect. But there will be infringement if the sign is used, without authority, "to create the impression that there is a material link in the course of trade between the goods concerned and the trade mark proprietor" . . .’

[7] This approach appears to me to be eminently sensible. It gives effect to the purpose of the Act and attains an appropriate balance between the rights of the trade mark owner and those of competitors and the public. What is, accordingly, required is an interpretation of the mark through the eyes of the consumer as used by the alleged infringer. If the use creates an impression of a material link between the product and the owner of the mark there is infringement; otherwise there is not. The use of a mark for purely descriptive purposes will not create that impression but it is also clear that this is not necessarily the definitive test.

[8] Turning then to the facts of this case, I am satisfied that any customer would regard the presence of the logo on the picture of the BMW car as identifying the car and being part and parcel of the car. It is use of the car to illustrate Diamond Guard’s properties rather than use of the trade mark.12 No-one, in my judgment, would perceive that there exists a material link between BMW and Diamond Guard or that the logo on the car performs any guarantee of origin function in relation to Diamond Guard.

[9] Counsel for BMW sought to escape this conclusion by relying on dicta in Adidas13 where AS Botha J dealt with the distinction between trade mark infringement and passing-off and where he mentioned that in the former instance one simply has to compare the two marks as registered without reference to the get-up whereas in the latter case one has to have regard to the whole get-up when determining whether or not there is a probability of confusion or deception. This dictum is, in context, correct although it has from time to time been used to blur the distinction between added matter extrinsic to a defendant’s mark and added matter that is intrinsic thereto.14 In any event, the dictum dealt with the issue of determining identity or the likelihood of confusion or deception and not with the determination of the public’s perception of what the defendant’s mark is.15 Here the issue is whether the public would perceive the BMW logo to perform the function of a source identifier and for that purpose one cannot simply isolate the logo on the bonnet of the car and ignore the context of use.

[10] The effect of this is that BMW’s claim based on s 34(1)(a) was misconceived and that the high court erred in granting an interdict in relation to the polish mark. Verimark’s appeal must therefore be upheld.

[11] This brings me to BMW’s case based on s 34(1)(c) – the anti-dilution provision – which provides (to the extent relevant) that the unauthorized use in the course of trade in relation to any goods of a mark identical to a registered trade mark, if the latter is well known in the Republic and the use of the mark would be likely to take unfair advantage of, or be detrimental to, the distinctive character or the repute of the registered trade mark amounts to trade mark infringement, notwithstanding the absence of confusion or deception.

[12] It is common cause that the BMW logo is well known16 and that the issue is whether Verimark’s use as described is likely to take ‘unfair advantage’ of the distinctive character or the repute of the BMW mark, in other words, whether there is the likelihood of dilution through an unfair blurring of BMW’s logo, it being accepted that Verimark’s use is not detrimental to nor does it tarnish BMW’s logo.

[13] Contrary to rather wide dicta in Johnstone (at para 17)17 stating the opposite, the position in our law is that this provision does not require trade mark use in the sense discussed as a pre-condition for liability. In other words, the provision ‘aims at more than safeguarding a product’s “badge of origin” or its “source-denoting function”.’18 It also protects the reputation, advertising value or selling power of a well known mark.19 But that does not mean that the fact that the mark has been used in a non trade mark sense is irrelevant; to the contrary, it may be very relevant to determine whether unfair advantage has been taken of or whether the use was detrimental to the mark.

[14] The following points made by Lord Menzies with reference to a number of authorities are in this context apposite:20 the provision is not intended to enable the proprietor of a well-known registered mark to object as a matter of course to the use of a sign which may remind people of his mark; there is a general reluctance to apply this provision too widely; not only must the advantage be unfair, but it must be of a sufficiently significant degree to warrant restraining of what is, ex hypothesi, non-confusing use; and that the unfair advantage or the detriment must be properly substantiated or established to the satisfaction of the court: the court must be satisfied by evidence of actual detriment, or of unfair advantage.21

[15] The high court found that although Verimark may be taking advantage of the reputation of the BMW logo, this is not done in a manner that is unfair. It mentioned that Verimark’s emphasis is on the effectiveness of its own product sold under established trade marks and found that one cannot expect Verimark to advertise car polish without using any make of car and it would be contrived to expect of Verimark to avoid showing vehicles in such a way that their logos are hidden or are removed. I agree. As before, the question has to be answered with reference to the consumer’s perception about Verimark’s use of the logo. Once again, in my judgment a consumer will consider the presence of the logo as incidental and part of the car and will accept that the choice of car was fortuitous. In short, I fail to see how the use of the logo can affect the advertising value of the logo detrimentally. A mental association does not necessarily lead either to blurring or tarnishing.22

[16] This means that the high court was correct in its dismissal of the claim for an interdict in relation to the car mark and that the cross-appeal stands to be dismissed. The resultant order is the following:

(a) The appeal is upheld and the cross-appeal dismissed with costs, such costs to include the costs of two counsel.

(b) The order of the court below is amended to read:

‘The application is dismissed with costs.’

___________________________

L T C HARMS

ACTING DEPUTY PRESIDENT

AGREE:

STREICHER JA

CLOETE JA

PONNAN JA

COMBRINCK JA

1 The representation of the logo below is of a better quality than the one on the registration certificate.

2 It reads as follows:

‘34(1) The rights acquired by registration of a trade mark shall be infringed by—

(a) the unauthorized use in the course of trade in relation to goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is registered, of an identical mark or of a mark so nearly resembling it as to be likely to deceive or cause confusion;

(b) the unauthorized use of a mark which is identical or similar to the trade mark registered, in the course of trade in relation to goods or services which are so similar to the goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is registered, that in such use there exists the likelihood of deception or confusion;

(c) the unauthorized use in the course of trade in relation to any goods or services of a mark which is identical or similar to a trade mark registered, if such trade mark is well known in the Republic and the use of the said mark would be likely to take unfair advantage of, or be detrimental to, the distinctive character or the repute of the registered trade mark, notwithstanding the absence of confusion or deception: Provided that the provisions of this paragraph shall not apply to a trade mark referred to in section 70 (2).’

3 Two other marks were also in contention but they did not figure during argument on appeal and, in any event, the outcome of this appeal makes it unnecessary to consider them separately. BMW’s reliance on passing-off was abandoned during the appeal hearing.

4R v Johnstone [2003] UKHL 28, [2003] 3 All ER 884, [2004] ETMR 2, [2003] 1 WLR 1736, [2003] FSR 42, [2003] 2 Cr App R 33 at para 76.

5 Especially R v Johnstone. As for Scotland: Procurator Fiscal v. Gallacher [2006] ScotSC 40.

6Bergkelder Beperk v Vredendal Koöp Wynmakery 2006 (4) SA 275 (SCA), [2006] 4 All SA 215 (SCA) footnote 15.

7Abbott Laboratories v UAP Crop Care (Pty) Ltd 1999 (3) SA 624 (C) 632B-C and Abdulhay M Mayet Group(Pty) Ltd v Renasa Insurance Co Ltd 1999 (4) SA 1039 (T) 1045I-J

8Anheuser-Busch Inc. v Budĕjovický Budvar, národní podnik Case C-245/02 of 16 November 2004.

9See Arsenal Football Club Plc v Reed [2003] EWCA Civ 696 (21 May 2003). There are many cases under this name.

10R v Johnstone [2003] UKHL 28. Although delivered at approximately the same time the House was apparently unaware of the proceedings in the Court of Appeal mentioned in the preceding footnote, and vice versa.

11In Arsenal Football Club plc v Reed [2003] RPC 144; [2002] EUECJ C-206/01 (12 November 2002).

12 Cf Jeremy Phillips Trade Mark Law (2003) para 8.52-8.55.

13Adidas Sportschuhfabriken Adi Dassler KG v Harry Walt & Co (Pty) Ltd 1976 (1) SA 530 (T) 535E-536A

14 For an explanation of the difference see: Standard Bank of SA Ltd v United Bank Ltd 1991 (4) SA 780 (T); Bata Ltd v Face Fashions CC 2001 (1) SA 844 (SCA) para 6; Reed Executive plc v Reed Business Information Ltd [2004] EWCA Civ159, [2004] RPC 40; Compass Publishing BV v Compass Logistics [2004] EWHC 520, [2004] RPC 41 (Ch).

15 Cf Miele et Cie & Co v Euro Electrical (Pty) Ltd 1988 (2) SA 583 (A) 596F-I; Apple Corps Ltd v Apple Computer Inc [2006] EWHC 996 (Ch).

16 Whether the logo is well known in relation to polishes has not been established but this fact has no bearing on the outcome of the case.

17 These appear to require trade mark use for the anti-dilution provision also. The dicta are explicable because the case dealt with counterfeiting and counterfeiting is concerned with primary infringement and does not concern dilution.

18Laugh It Off Promotions CC v SAB International (Finance) BV t/a Sabmark International 2006 (1) SA 144 (CC) para 40.

19Laugh It Off Promotions CC v SAB International (Finance) BV t/a Sabmark International 2005 (2) SA 46 (SCA) para 13.

20Pebble Beach Company v Lombard Brands [2002] ScotCS 265.

21Depending on the primary facts these may be self-evident. On the requirement of proof of actual detriment see Laugh It Off Promotions CC v SAB International (Finance) BV t/a Sabmark International 2006 (1) SA 144 (CC) para 49.

22Cf Moseley v V Secret Catalogue 537 US 418 (2003), 4 Mar 2003 per Stevens J: ‘We do agree, however, with that court’s conclusion that, at least where the marks at issue are not identical, the mere fact that consumers mentally associate the junior user’s mark with a famous mark is not sufficient to establish actionable dilution. As the facts of that case demonstrate, such mental association will not necessarily reduce the capacity of the famous mark to identify the goods of its owner, the statutory requirement for dilution under the FTDA. For even though Utah drivers may be reminded of the circus when they see a license plate referring to the “greatest snow on earth,” it by no means follows that they will associate “the greatest show on earth” with skiing or snow sports, or associate it less strongly or exclusively with the circus. “Blurring” is not a necessary consequence of mental association. (Nor, for that matter, is “tarnishing.”)’

Cited documents 0

Documents citing this one 8

Judgment 8

- African National Congress v uMkhonto weSizwe Party and Another (D153/2024) [2024] ZAKZDHC 14 (22 April 2024)

- Bousaada (Pty) Ltd and Another v FCB Africa (Pty) Ltd and Another; FCB Africa (Pty) Ltd v Bousaada (Pty) Ltd and Another (16949/2021) [2023] ZAGPJHC 717 (14 June 2023)

- Golden Fried Chicken (Pty) Ltd v Vlachos and Another (497/2021) [2022] ZASCA 150 (3 November 2022)

- ICollege (Pty) Ltd v Xpertease Skills Development and Mentoring CC and Another (106/2022) [2023] ZASCA 70 (24 May 2023)

- LA Group (Pty) Ltd v Stable Brands (Pty) Ltd and Another (650 of 2020) [2022] ZASCA 20 (22 February 2022)

- National Brands Ltd v Cape Cookies CC and Another (309/2022; 567/2022) [2023] ZASCA 93 (12 June 2023)

- Puma AG Rudolf Dassler Sport v Global Warming (Pty) Ltd (408/2008) [2009] ZASCA 89 (11 September 2009)

- Yuppichef Holdings (Pty) Ltd v Yuppie Gadgets Holdings (Pty) Ltd (1088 of 2015) [2016] ZASCA 118 (15 September 2016)