|

Editorial note: Certain information has been redacted from this judgment in compliance with the law. |

THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEAL OF SOUTH AFRICA

JUDGMENT

Reportable

Case No: 20719/2014

In the matter between:

ABSA BANK LIMITED APPELLANT

And

CHRISTINA MARTHA MOORE FIRST RESPONDENT

JACQUES MOORE SECOND RESPONDENT

Neutral Citation: Absa v Moore (20719/2014) [2015] ZASCA 171 (26 November 2015)

Coram: Lewis, Ponnan, Pillay and Saldulker JJA and Van der Merwe AJA

Heard: 6 November 2015

Delivered: 26 November 2015

Summary: Where a sale giving rise to the transfer of immovable property is induced by fraudulent misrepresentation, such that the owner does not intend to transfer ownership, registration of the transfer is of no force. A person who is not the owner of immovable property cannot grant a valid mortgage bond over it.

___________________________________________________________________

ORDER

On appeal from: Gauteng Local Division of the High Court, Johannesburg (Chohan AJ sitting as court of first instance):

The appeal is dismissed with the costs of two counsel, where so employed, save that para 3 of the order of the court a quo is replaced with:

‘The applicants are the owners of the property situate at Erf [1…..], [T….. R…….] [E….. T…..] IR Gauteng.’

___________________________________________________________________

JUDGMENT

Lewis JA (Ponnan, Pillay and Saldulker JJA and Van der Merwe AJA concurring)

[1] This appeal concerns a fraudulent scheme devised and implemented by Brusson Finance (Pty) Ltd (Brusson), and to which many individuals and various banks have fallen victim. Brusson has been liquidated and the fallout has left individuals to litigate against banks in an attempt to preclude sales in execution of their homes. Courts in the Free State and in Gauteng, where Brusson seems to have defrauded most of their victims, have dealt with matters in different ways and Brusson transactions have, to some extent, been differently structured in respect of each victim.

[2] In the matter before us, the respondents Ms Christine Moore and her husband Mr Jacques Moore, live in a home in Vereeniging, on Erf [1…..], [T….. R……. E……], Gauteng. The street address is 6 [E….. A…….], [T….. R…… E……], Vereeniging. The property was registered in the name of Ms Moore. She is married in community of property to Mr Moore. The property was subject to five mortgage bonds in favour of the appellant, Absa Bank Ltd (the Bank), and the amount owing to the Bank in May 2009 was some R145 000. The Moores were in arrear in the payment of the instalments on the bond. They were unable to pay other debts as well. When they applied for an extension of their home loan the Bank declined to grant it because of their poor credit rating. They were in dire financial straits.

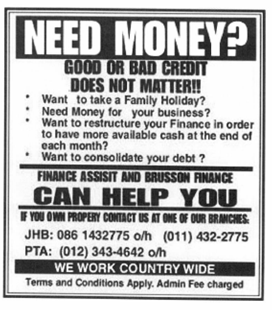

[3] The Moores chanced upon an advertisement in the local newspaper for Brusson financing. The advertisement appears as follows:

[4] The Moores required a loan of some R220 000. Mrs Moore contacted Brusson on the telephone number set out in the advertisement, and spoke to a representative. She was apparently keen to assist the Moores provided that they had property to use as security for the loan. Brusson faxed to the Moores various documents that they were required to fill in to facilitate their application for a loan. They subsequently went to a Brusson office and signed three documents which they believed gave effect to a loan to them and provided security for repayment of the loan in the form of a bond over their property to Brusson. I shall return to the terms of the documents and what the Moores were led to believe was their effect. In summary, the first of the three documents was an ‘Offer to Purchase’ in terms of which a person (the name of the purchaser, Mr Sunnyboy Kabini, was later inserted, but not by the Moores) offered to buy the Moores’ home for R686 000, payable on transfer of the property to him. The second was a ‘Deed of Sale’ in terms of which Mr Kabini sold the property back to the Moores, the price to be paid in instalments. The third was a ‘Memorandum of Agreement’ between Brusson, the Moores and Mr Kabini that regulated their tripartite relationship.

[5] The Moores signed all three documents on 12 May 2009. On 31 June 2009 Mr Kabini applied to the Bank for a home loan, secured by a mortgage bond over the property. The loan was granted. On 24 August 2009 the property was transferred to Mr Kabini and a mortgage bond over it was registered in favour of the Bank. Five bonds, all in favour of the Bank where the Moores were the mortgagors, were simultaneously cancelled. The Moores were unaware that the property was transferred and that a new bond was registered in favour of the Bank.

[6] Before then, and soon after their visit to the Brusson office, an amount of R157 651 was paid into their bank account. They believed this to be the loan from Brusson that would tide them over their financial plight. Brusson informed them that this amount would be repayable in monthly instalments of R6 907 that would include interest.

[7] The Moores could not pay these monthly instalments, and on 2 November 2009 Ms Moore applied for debt review under the National Credit Act 34 of 2005. A debt counsellor was appointed and he applied to the Magistrates’ Court, Vereeniging, for a restructuring of their debt obligations. He recorded the debt owing to Brusson as a ‘bond’. In terms of the court order the Moores were required to repay Brusson only R3 058 a month.

[8] In July 2010, the Moores received a letter from an attorney, Mr T C Hitge, written on behalf of Brusson, advising that they were in breach of their obligation to pay to Brusson the monthly instalment of R6 907. Significantly, Mr Hitge advised that the instalments were payable in terms of the ‘Offer to Purchase and Instalment Sale Agreement’ with Mr Kabini. The arrears said to be owing to Brusson at that stage amounted to R43 597. He threatened the Moores with legal action.

[9] The Moores reacted to the letter by instructing an attorney, Mr W van Vuuren, who, on 13 October 2010, wrote a letter of complaint to the National Credit Regulator. Mr Van Vuuren advised the Regulator that the Moores had approached Brusson when they experienced financial difficulty, and were under the impression that an investor, Mr Kabini, would lend them money and that the property would be the security for the loan. He referred to the letter from Mr Hitge, and advised that it was the first time that the Moores had received notice that they had apparently sold their property to Mr Kabini. He also advised that the Moores had applied for debt review, that the monthly instalments payable to Brusson had been reduced and that Brusson had been told of this.

[10] Mr van Vuuren referred the Regulator to the decision of Jordaan J in Ditshego v Brusson Finance (Pty) Ltd in the Free State High Court (unreported case no 5144/2009, handed down on 22 July 2010) in which the court had held that similar contracts with Brusson were invalid. He asked the Regulator for advice on how to proceed on behalf of the Moores. Apparently no response to this letter was received, and the Moores said they could not afford to pay a lawyer to represent them anymore.

[11] On 23 March 2011, the Bank issued summons against Mr Kabini, who was in default of his obligations under the bond. It took judgment by default on 12 July 2011 for payment of R500 067 plus interest and costs. The court declared the property specially executable. On 3 August 2011 the Bank issued a writ of execution and a notice of attachment of the property was served at the property of the Moores. It was addressed to Mr Kabini, but it referred specifically to 6 [E….. A……], [T….. R….. E…..], Vereeniging, which was of course occupied by the Moores. The Sheriff noted that it was received on 26 August 2011. The Moores knew then that the property was attached in execution of Mr Kabini’s debt to the Bank.

[12] No further steps were taken after that by the Moores. It was only when the Moores received a letter from Resque Financial Solutions, that was sent to Mr Kabini at their address, that they realized that their home was going to be sold in execution of someone else’s debt. The letter was dated 17 May 2013 and was received on 23 May. It was then that the Moores took action. They approached the Legal Resources Centre (LRC) for legal advice. The LRC had been approached by several other victims of the Brusson scam and it wrote immediately, on 27 May 2013, to the Sheriff, Vereeniging and to the attorneys for the Bank, requesting the stay of the execution, and stating that, if not stayed, the Moores would bring an urgent application to prevent the sale.

[13] On 28 May 2013 the Moores brought an urgent application to interdict the sale of the property in the South Gauteng High Court, and for the rescission of the default judgment against Kabini. The application for the interdict was granted on 30 May 2013. And on 24 June 2013 they applied for declaratory orders that the three agreements be declared invalid, that Ms Moore was entitled to restitution of the property and that the mortgage bond over the property was invalid and should be set aside. The applications were brought against the Sheriff for the District of Vereeniging, Mr Kabini, the Bank (as third respondent), the liquidators of Brusson and the Registrar of Deeds.

[14] Only the Bank opposed the applications. They were consolidated and heard by Chohan AJ (in what had been renamed the Gauteng Local Division of the High Court), who found for the Moores, and handed down judgment on 26 September 2013. The appeal against the orders of the court a quo is with its leave. That court found that the agreement concluded between the Moores and Brusson, and the agreements between the Moores and Mr Kabini, were ‘invalid, unlawful and of no force and effect’. It also ordered that the Moores were entitled to restitution of the property subject to two conditions: the reinstatement of the five mortgage bonds that had been previously been registered over the property; and the Moores paying the Bank the amount that they had received from Brusson, less any amounts that they had paid to it. The court also set aside the mortgage bond over the property and the default judgment, (in so far as at permitted execution) against Mr Kabini. It ordered the parties to pay their own costs, having found that the Moores were in some respects to blame for their predicament. The Moores have not cross-appealed against the order that the restitution of their property be subject to conditions, nor against the costs order.

The issues on appeal

[15] The Bank now focuses first on whether the court a quo correctly found that the Moores were entitled to an order setting aside the mortgage bond, or an order that deprives the Bank of its real right in the property. Secondly, the Bank argues that it should not be deprived of its real right over the property when it was innocent of any wrongdoing. The Bank argues that it advanced R480 000 to Mr Kabini in good faith against the security of the bond and that the bond stands independently of the invalid transactions. The Moores argue, on the other hand, that Mr Kabini did not ever acquire ownership of the property and therefore could not grant security in the form of a bond over the property.

[16] I shall return to these arguments as they are the crux of the appeal, but wish first to clarify the law on which the court a quo’s judgment was based, its findings and those of other courts that have dealt with the Brusson scam. Other grounds of appeal, including that the agreement with Brusson did not amount to a pactum commissorium, and that the agreements did not contravene the National Credit Act, were not pursued at the hearing of the appeal.

[17] Moreover, the argument raised by the Bank in its heads of argument on appeal, that the Moores should be estopped from disputing the validity of the transfer of their property to Mr Kabini, was also not pursued at the appeal hearing. In its heads of argument the Bank had also contended that the Moores had signed the documents, which they had had ample opportunity to read, and were precluded from arguing that the documents did not reflect their consensus by the principle underlying the maxim caveat subscriptor. The principle is of no application in the face of fraud and the argument was thus rightly not pursued at the appeal hearing.

The Brusson scam and the agreements that the Moores signed

[18] It is necessary, however, before turning to the legal principles on which the court a quo, and other courts found, to deal with the salient provisions of the agreements between the Moores, Brusson and Kabini. The first agreement signed was headed ‘Offer to Purchase’. The Moores, on the face of it, sold their property to Mr Kabini for payment of the purchase price of R686 000, payable on transfer. The sale was conditional on Mr Kabini raising a loan, against a bond, of R480 000. Occupation of the property was to be given to the Moores (despite the fact that they were already in occupation) on transfer, and they were required to pay a monthly sum in consideration for occupation of R7 909. The contract also required the Moores to pay a commission of R47 910 to Brusson.

[19] The ‘Deed of Sale’ between the Moores and Mr Kabini provided that he sold the property back to the Moores for R648 000, payable in monthly instalments of R7 578 plus interest. The full outstanding balance had to be paid within 36 months, and on that happening, Mr Kabini would transfer the property back to the Moores. Payment of the instalments was to be made to Brusson, not Mr Kabini, and in addition, the Moores were required to pay an administration fee of some R2 207 monthly to Brusson. Mr Kabini was required to pay to Brusson an amount of R168 000 in consideration for Brusson standing surety for his obligations.

[20] The third contract was the tripartite ‘Memorandum of Agreement’ that regulated the relationship of Brusson, the Moores and Mr Kabini. It reflected the obligations already purportedly arising out of the other two agreements.

[21] As I have indicated, the three contracts are typical of those that have been examined by the provincial divisions in other matters involving the Brusson scam, and the divisions have generally followed the same approach in deciding that the contracts signed by victims of the scam are invalid.

The approach of the court a quo and other courts

[22] The decisions dealing with the Brusson scam include Ditshego v Brusson Finance (Pty) Limited [2010] ZAFSHC 68 (above); Cloete NO v Basson [2010] ZAGPJHC 87 (4 October 2010); Absa Bank v Boshoff [2012] ZAECPEHC 58 (28 August 2012); Leshoro v Nedbank [2014] ZAFSHC 69 (20 March 2014); Mabuza v Nedbank [2014] ZAGPPHC 513 2015 (3) SA 365 (GP); Barnard v Nedbank [2014] ZAGPPHC 723 (11 September 2014) and Radebe v Sheriff for the District of Vereeniging [2014] ZAGPJHC 228 (25 September 2014).

[23] In Ditshego (followed by the court a quo in this matter) Jordaan J in the Free State High Court held that the contracts were all interrelated and interdependent, such that there was in effect only one transaction, and that was invalid. He regarded several features of the transaction as unusual and ‘foreign’ to bona fide agreements of sale of immovable property. The court had regard not only to the contracts themselves, but also to a brochure describing the Brusson scheme, produced by Brusson as client information. (In her founding affidavit to the application for declaratory relief, Ms Moore attached a similar brochure explaining the scheme.) I deal only with those common to the transaction in this matter.

[24] The unusual features include: the investor does not really intend buying the property and never takes occupation; the client does not really intend selling the property and does not lose occupation; the investor pays nothing, but applies for a bond over the property as he has a good credit rating; the price payable in terms of the instalment sale agreement accrues not to the investor but to Brusson; all payments are made to Brusson; in the event of default by the clients, Brusson is entitled to take transfer of the property.

[25] Jordaan J concluded that the contracts were simulated and accordingly invalid. He did not deal with the validity of the bond over the property. In finding that the transaction was simulated, Jordaan J relied on Maize Board v Jackson 2005 (6) SA 592 (SCA) para 8. There, following a long line of cases in this court, Ponnan JA held that the true enquiry, in determining whether contracts are simulated, ‘is to establish whether the real nature and the implementation of these particular contracts is consistent with their ostensible form. In pursuit of the enquiry, one must strive to ascertain, from all of the relevant circumstances, the actual meaning of the contracting parties.’ This court referred to an earlier decision in Michau v Maize Board 2003 (6) SA 459 (SCA) para 4, and the authorities cited there, which have held over decades that parties may not conceal the true nature of their transaction. See, more recently, Commissioner for the South African Revenue Service v NWK Ltd 2011 (2) SA 67 (SCA) paras 40-55; Roshcon (Pty) Ltd v Anchor Auto Body Builders CC & others 2014 (4) SA 319 (SCA) paras 22-37; and Commissioner, South African Revenue Service v Bosch & another 2015 (2) SA 174 (SCA) paras 38-41, in all of which the principles dealing with simulated transactions are discussed in depth.

[26] In cases dealing with the Brusson scam the courts have by and large held the transactions to be simulated. But I consider that they are not. The Moores and other victims of the scam certainly did not intend to disguise their contracts as something they were not. On the contrary: they were hoodwinked as to the nature of the transactions. They believed them to serve some other purpose entirely. The Brusson transactions, certainly the ones before the Free State High Court and the court a quo, were not simulated in the sense in which that term is properly used. The question is whether they were rendered invalid as a result of a fraud perpetrated on the victim client. And the further question is what the victim clients really intended to achieve by contracting with Brusson and so-called investors.

[27] The distinction is an important one. Where a transaction pursuant to which property is to be transferred is simulated – where all parties intend to disguise the true nature of the transaction – the transferor and transferee may well intend to transfer ownership. And since a valid transaction is not required for a transfer to be effected, the transfer itself may not be impeached. I shall deal with the legal principles when considering the Moores’ understanding of their contracts with Mr Kabini and Brusson and accordingly their intention. Suffice to say for the moment that it is only where the parties do not intend to change the ownership of the property, but have been misled into purporting to do so, or for some other reason that vitiates their intention to transfer property, such as undue influence or duress, that the transfer will be of no effect.

[28] That was appreciated by Nicholls J in Radebe (above) where she held that the clients had not intended to transfer ownership of their property and that the so-called transferee could not validly register a bond over that property. The court a quo followed the reasoning in Radebe but also considered that the contracts between the Moores, Brusson and Mr Kabini were simulated. I now turn to the analysis of the facts by Chohan AJ.

The findings of the court a quo

[29] As I have said, Chohan AJ found that the contracts between the Moores, Mr Kabini and Brusson were simulated and thus void. This despite his view that the result was ‘difficult to reconcile’ with certain facts. These were that (a) the offer to purchase in express terms provided for the transfer of the property to the purchaser, although Mr Kabini’s name did not appear on the document that the Moores signed; (b) the Moores would have signed the relevant transfer documents to enable the Registrar of Deeds to transfer their property to Mr Kabini (the judge remarked that the papers were silent on this point, but in fact they were not); (c) the Moores required a loan of only R220 000 whereas the purchase price of the property was R686 000; (d) there were five bonds over the property and the Moores ceased paying the Bank; (e) the papers did not disclose the market value of the property when the agreements were concluded; (f) the papers did not disclose whether the Moores had continued to pay rates and service charges; (g) when the Moores applied for a debt review they identified their debt to Brusson as a bond; and finally, (h) when the Moores received the notice of attachment on 26 August 2011 they took no steps to ascertain why their property was being attached.

[30] Several of these findings are quite simply wrong. It is true that the agreement with Mr Kabini, signed before it was completely filled in, was headed ‘offer to purchase’. But Mrs Moore explained in her founding affidavit that the Brusson representative had told them that the documents simply served to give Brusson security over the property for repayment of the loan. She said:

‘While we were at Brusson House, Brusson explained to us that the documents we were signing were just to confirm that the property was being provided as security for the loan. In particular, no one explained that the agreements were for the sale of the property. I also did not take independent advice at the time, since I was desperate and grateful for the financial assistance provided by Brusson and believed that the representations given by Brusson were correct.

[We] did not understand that we were concluding a sale of our property. We believed that Brusson was assisting us in obtaining a loan. If it had been made clear to us that in order to secure the loan, we had to sell our property to a third party, we would never have entered into the transaction.

[We] signed the documents because of what was explained to us, namely that the documents pertain to our request for a loan.’

The Bank did not counter these averments. They stand uncontradicted and must be accepted.

[31] The Moores also explained that they had never seen a conveyancer or instructed one to transfer their property. They thus did not understand how the transfer occurred. Again, the Bank put up no evidence to controvert this. Not even the conveyancer’s evidence was put to counter this. The judge a quo thus erred in finding that it was inconceivable that they had not signed documents authorizing the transfer.

[32] As to the difference in the amounts required by the Moores (R220 000) and the ‘price’ of the property (R686 000), Mrs Moore explained that they required R145 000 to pay off their debt to the Bank. They had other debts to pay off. They in fact received R157 651 from Brusson. They did not realize the ‘price’ Mr Kabini allegedly paid was R686 000.

[33] The Moores’ version of why they no longer paid the Bank in respect of the five bonds formerly registered over the property is consistent with what they believed had happened: Brusson had paid off those bonds, and registered one in its favour as security for the amount of the loan made to them by it – R157 651. They were required to pay bond instalments to Brusson instead. It was these instalments that they could not pay monthly, and which triggered their application for debt review. And so it was also quite understandable that their debt to Brusson was reflected by the debt counsellor as a ‘bond’ when they applied to court for a debt restructuring. None of this was denied by the Bank and so again any adverse inference that the court a quo drew was unjustified. Further, they were never called upon by the Bank to say whether they had continued to pay rates and service charges. The fact that they said nothing about this is thus irrelevant.

[34] The issue on which the Bank places most store is that the Moores failed to do anything after they received the notice of attachment in August 2011. This is not adequately explained by the Moores. But it will be recalled that when they received the letter from Brusson’s attorney in July 2010, they instructed an attorney who responded by writing to the National Credit Regulator asking for advice on how to proceed. There is no evidence to suggest that they must have continued to believe that there was a problem that needed to be resolved.

[35] The Bank argues on appeal that the findings of the court a quo were not taken into account sufficiently by the court itself when it concluded that the transactions were simulated. It ‘artificially devalued’ the correct factual findings. However, the findings were, as I have said, unwarranted given the absence of evidence put up by the Bank to show that the averments made by the Moores were wrong. The Bank’s argument that those averments were inherently improbable is also untenable. The Moores explained just how it happened that they became a victim of the Brusson scam. They were induced to enter into the contracts by fraudulent misrepresentations made by Brusson.

The transfer of the property and the validity of the bond in favour of the Bank

[36] The court a quo found that the transfer was nonetheless invalid, and that the bond was also invalid given that the Moores had not intended to transfer their property to anyone, let alone Mr Kabini. It relied in this regard on Nedbank v Mendelow 2013 (6) SA 130 (SCA) where I held (paras 13 and 14):

‘This court has recently reaffirmed the principle that where there is no real intention to transfer ownership on the part of the owner or one of the owners, then a purported registration of transfer (and likewise the registration of any other real right, such as a mortgage bond) has no effect. In Legator McKenna Inc & another v Shea & others [2010 (1) SA 35 (SCA) paras 21 and 22] Brand JA confirmed, first, that the abstract theory of transfer of ownership applies to immovable property, and second, that if there is any defect in what he termed the ‘real agreement’ – that is, the intention on the part of the transferor and the transferee to transfer ownership of a thing respectively – then ownership will not pass despite registration. Thus while a valid underlying agreement to pass ownership, such as a sale or donation, is not required, there must nonetheless be a genuine intention to transfer ownership. This principle was unanimously approved in Commissioner of Customs and Excise v Randles, Brothers & Hudson Ltd [1941 AD 369] and has been followed consistently since then.

However, if the underlying agreement is tainted by fraud or obtained by some other means that vitiates consent (such as duress or undue influence) then ownership does not pass: Preller & others v Jordaan [1956 (1) SA 483 (A) at 496.]’

[37] I referred also to Meintjies NO v Coetzer & others 2010 (5) SA 186 (SCA) para 9 and Gainsford & others NNO v Tiffski Property Investments (Pty) Ltd & others 2012 (3) SA 35 (SCA) paras 38 and 39. To these must be added Quartermark Investments (Pty) Ltd v Mkhwanazi & another 2014 (3) SA 96 (SCA) paras 21-25. These cases all confirm the same fundamental legal principle: where the so-called transferor does not intend to transfer ownership the registration has no effect.

[38] The court a quo thus correctly held that Mr Kabini had not acquired ownership of the property. The question that remains is whether the mortgage bond registered to secure the Bank’s loan to him is also invalid. It is clear from the decisions referred to above that the bond also has no effect. Mr Kabini was not the owner. He had no property to bond. And the court a quo correctly held that the bond was also invalid. That was the finding also of Nicholls J in Radebe, referred to earlier.

[39] The Bank argued on appeal that even if Mr Kabini was not the owner of the property he had nonetheless intended to register a bond over the property. But that is of no relevance. He simply did not have the legal capacity to register that bond over that property. He could not grant a real right in property that he did not own.

[40] The Bank contends that it should not be left without legal recourse as it too is the innocent victim of a scam. It also argues that the Moores should not benefit from the fact that their property will be bond-free, if we find that the bond is invalid, especially given that they were in some way to blame for their predicament. In my view all parties were innocent victims of a fraudulent scheme.

The order of the court a quo

[41] The Bank argues that if we find that the bond is invalid, we should at least refine the order made by the court a quo, and order the Moores to pay what they have tendered to pay to the Bank, against registration of a bond securing that amount. It will be recalled that the order was that the Moores were entitled to restitution of the property subject to the reinstatement of the five bonds over it and payment by the Moores of the amount they received from Brusson, less any of the payments that they made to it. That order, the Bank argues, should be made subject to time limits.

[42] However, I do not understand on what basis the order in question was made. The Bank did not ask for such relief in the event that the bond in its favour was found to be invalid. And this court cannot make a contract between the Bank and the Moores. We cannot order that the Moores pay an amount that they did not owe to the Bank, nor that they register a bond over their property in favour of the Bank. There is no longer any contractual nexus between these parties. The court a quo simply did not have the power to make a contract for the parties. Thus even though the Moores did not cross-appeal against that order this court cannot uphold it.

[43] The Bank still has a claim for repayment of the loan against Mr Kabini, albeit unsecured. And it may also have a claim against the conveyancer responsible for the registration of the bond in the first place. Section 15A(1) of the Deeds Registries Act 47 of 1937 provides that a conveyancer who prepares a document for the purpose of registration in a deeds registry, and who signs the prescribed certificate required in order to do so, ‘accepts by virtue of such signing the responsibility, to the extent prescribed by regulation for the purpose of this section, for the accuracy of those facts’ mentioned in the document. Regulation 44A of the regulations sets out the particulars which the conveyancer must provide and repeats the statement that he or she is responsible for the facts certified.

Rescission of the default judgment

[44] Finally, the court a quo ordered that the default judgment and order as to executability granted to the Bank against Mr Kabini should be set aside. The Bank argued before the court a quo that the Moores had no locus standi to apply for the rescission of the judgment and order against Mr Kabini. It has not pressed this argument on appeal. Chohan AJ correctly found that in terms of Rule 42(1)(a) of the Uniform Rules of Court, the Moores were entitled to apply for rescission of the default judgment. The rule reads:

‘The court may, in addition to any other powers it may have, mero motu or upon the application of any party affected, rescind or vary –

-

An order or judgment erroneously sought or erroneously granted in the absence of any party affected thereby; . . .’

The Moores were quite obviously parties affected by the judgment, and, had the court asked to make the order been aware of the true facts it would most certainly not have granted it. (See, most recently, on the circumstances in which an application for rescission under rule 42(1)(a) will be granted Minnaar v Van Rooyen NO [2015] ZASCA 114.)

[45] However, the Bank’s further argument, pressed on appeal, was that the Moores should be precluded from obtaining rescission of the default judgment because of their delay in seeking the relief. Despite knowing of the writ of attachment in August 2011 they took no steps to set the default judgment aside until May 2013 when they were advised that their property was to be sold in execution of Mr Kabini’s debt. The Bank accepts that in deciding whether to rescind a default judgment the court has a discretion, but contends that the two-year delay was unreasonable and inexcusable.

[46] As a matter of fact, as I mentioned earlier, the Moores learned of the existence of the default judgment and proposed sale in execution only in May 2013. They had before then, on receiving the notice of attachment, taken steps by instructing an attorney who wrote to the National Credit Regulator. That they thereafter did nothing may be worth criticizing. But it was up to the Bank to show why it was entitled to sell in execution the property of the Moores when it had taken the default judgment against Mr Kabini: it had to show that it had the right to take default judgment in the first place.

[47] In any event, a court, when exercising a discretion to rescind an order given by default, must weigh against the delay the prospect of success of the application. The prospect of the Moores’ success was strong, and there was no reason to preclude them from obtaining the rescission that they sought.

[48] Although I consider that the costs order made by the court a quo (that each party would bear its own costs) was unjustified, there is no cross-appeal against it and the Moores accept that it should stand.

[49] In the result the appeal is dismissed with the costs of two counsel, where so employed, save that para 3 of the order is replaced with:

‘The applicants are the owners of the property situate at Erf [1…..], [T….. R….. E……] Township IR Gauteng.’

_______________________

C H Lewis

Judge of Appeal

APPEARANCES

For Appellant: A Gautschi SC (with him G W Amm)

Instructed by: Lowndes Dlamini, Sandton

Matsepes, Bloemfontein

For Respondent: W Trengove SC (with him P M P Ngcongo) (Heads of Argument also prepared by O Ben-Zeev)

Instructed by: Legal Resources Centre, Johannesburg

Webbers, Bloemfontein