- Flynote

-

Companies Act 61 of 1973 – s 252 – claim that manner in which the business of the company has been conducted was unfairly prejudicial, inequitable or unjust to plaintiffs – requirements for proof of unfair prejudice – whether company a small domestic company of the nature of a partnership – growth of company and introduction of a new major shareholder – effect of shareholders agreement on management of company – whether previous relationship between original shareholders continuing to exist – whether expectations based on previous relationship continuing to exist.

Dismissal of major shareholder as employee – whether unfair exclusion from company – effect of binding award by CCMA that dismissal neither procedurally nor substantively unfair – rule in Hollington v Hewthorn to be confined to decisions in criminal cases – test for admissibility of CCMA award whether relevant – prima facie proof that dismissal not unfair – onus on plaintiff to demonstrate that notwithstanding award dismissal unfairly prejudicial to him.

Shareholder no longer employed in company – locked in because unable to dispose of shares as provided in shareholders’ agreement – whether unfair prejudice if no offer made to acquire their shares – no obligation to make such an offer unless exclusion or other prior conduct caused unfair prejudice – no right of unilateral exit from the company at the cost of the company or the remaining shareholders – where no obligation to negotiate to acquire shares failure to do so not unfair.

Loss of trust and confidence by minority shareholders in management by majority – unfair prejudice if occasioned by lack of probity on part of the majority – necessary to show conduct that is dishonest or falls short of the standard of fair dealing required of majority in managing the affairs of the company – unfair prejudice not established by evidence that if managed differently company would have been more profitable.

Shareholder dispute – majority shareholders securing that the company’s funds are expended in defending the action – in principle improper if company has no material interest in the outcome of the litigation – where substantive relief is sought against company it is not a nominal defendant – does not mean that company’s resources should be used to defend the interests of the majority shareholders – company should only engage on matters having a direct impact on its own interests – remedy for improper use of company’s resources to fund litigation on behalf of shareholders an interdict and order that majority refund amounts disbursed in their interests – does not entitle minority shareholders to compel the company to expend its funds in payment of the minority’s costs.

Fair offer – considerations.

Buy-out – before ordering company to purchase minority’s shares court must consider impact on the company – form of order.

Fair trial – what constitutes – effect of a one-sided approach to issues - interruptions during cross-examination and restricting the time to be spent on cross-examination – need for civility in exchanges between judge and counsel.

3

THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEAL OF SOUTH AFRICA

JUDGMENT

Reportable

Case no: 613/2017

In the matter between:

TECHNOLOGY CORPORATE MANAGEMENT

(PTY) LTD FIRST APPLICANT

ANDREA CORNELLI SECOND APPLICANT

ANTONIO JOSE GARRIDO DA SILVA THIRD APPLICANT

IQBAL HASSIM NO FOURTH APPLICANT

BARRY KALMIN NO FIFTH APPLICANT

and

LUIS MANUEL RITO VAZ DE SOUSA FIRST RESPONDENT

JOSE MANUEL GARCIA DIEZ SECOND RESPONDENT

SHARON ANN OBEREM INTERVENING APPLICANT

Neutral citation: Technology Corporate Management (Pty) Ltd and Others v De Sousa and Another (Case No 613/2017) [2024] ZASCA 29 (26 March 2024)

Coram: WALLIS, MBHA, VAN DER MERWE, PLASKET and DLODLO AJJA

Heard: 30 and 31 October 2023

Delivered: 26 March 2024

Summary: Companies Act 61 of 1973 – s 252 – claim that manner in which the business of the company has been conducted was unfairly prejudicial, inequitable or unjust to plaintiffs – requirements for proof of unfair prejudice – whether company a small domestic company of the nature of a partnership – growth of company and introduction of a new major shareholder – effect of shareholders agreement on management of company – whether previous relationship between original shareholders continuing to exist – whether expectations based on previous relationship continuing to exist

Dismissal of major shareholder as employee – whether unfair exclusion from company – effect of binding award by CCMA that dismissal neither procedurally nor substantively unfair – rule in Hollington v Hewthorn to be confined to decisions in criminal cases – test for admissibility of CCMA award whether relevant – prima facie proof that dismissal not unfair – onus on plaintiff to demonstrate that notwithstanding award dismissal unfairly prejudicial to him.

Shareholder no longer employed in company – locked in because unable to dispose of shares as provided in shareholders’ agreement – whether unfair prejudice if no offer made to acquire their shares – no obligation to make such an offer unless exclusion or other prior conduct caused unfair prejudice – no right of unilateral exit from the company at the cost of the company or the remaining shareholders – where no obligation to negotiate to acquire shares failure to do so not unfair.

Loss of trust and confidence by minority shareholders in management by majority – unfair prejudice if occasioned by lack of probity on part of the majority – necessary to show conduct that is dishonest or falls short of the standard of fair dealing required of majority in managing the affairs of the company – unfair prejudice not established by evidence that if managed differently company would have been more profitable.

Shareholder dispute – majority shareholders securing that the company’s funds are expended in defending the action – in principle improper if company has no material interest in the outcome of the litigation – where substantive relief is sought against company it is not a nominal defendant – does not mean that company’s resources should be used to defend the interests of the majority shareholders – company should only engage on matters having a direct impact on its own interests – remedy for improper use of company’s resources to fund litigation on behalf of shareholders an interdict and order that majority refund amounts disbursed in their interests – does not entitle minority shareholders to compel the company to expend its funds in payment of the minority’s costs.

Fair offer – considerations.

Buy-out – before ordering company to purchase minority’s shares court must consider impact on the company – form of order.

Fair trial – what constitutes – effect of a one-sided approach to issues - interruptions during cross-examination and restricting the time to be spent on cross-examination – need for civility in exchanges between judge and counsel.

ORDER

On appeal from: Gauteng Division of the High Court, Johannesburg (Boruchowitz J, as court of first instance) reported sub nom: De Sousa and Another v Technology Corporate Management (Pty) Ltd and Others 2017 (5) SA 577 (GJ).

It is ordered that:

1 The application by the intervening applicant for conditional leave to intervene is dismissed and the intervening applicant is ordered to pay the costs of opposition by the first and second respondents in the main application, such costs to include the costs of one counsel.

2 The application for leave to appeal is upheld with costs, such costs to include the costs of the application for leave to appeal before the high court and the costs of two counsel.

3 The appeal is upheld with costs, including the costs of two counsel and the judgment of the High Court is altered to read as follows:

(a) The plaintiffs’ claim is dismissed with costs, such costs to include those consequent upon the employment of two counsel.

(b) The costs of the adjournment on 2 October 2012 including the costs consequent upon the employment of two counsel are to be costs in the cause in the action.

(c) The plaintiffs are ordered jointly and severally, the one paying the other to be absolved, to pay the costs of the application to amend the particulars of claim dated 9 December 2013 and the costs of the application in terms of Rule 35(3) dated 4 December 2015, such costs to include those consequent upon the employment of two counsel.

(d) Each party is to bear his or its costs of the application in terms of s 163 of the Companies Act 71 of 2008 and in respect of the recusal application by the first applicant.

JUDGMENT

Wallis AJA (Mbha, Van der Merwe, Plasket and Dlodlo AJJA concurring)

[1] The central issue in this application for leave to appeal is whether the high court’s order, under s 252 of the Companies Act 61 of 1973 (the Act), that the First Applicant, Technology Corporate Management (Pty) Ltd (TCM), purchase the shares in TCM owned by the First Respondent, Mr Luis de Sousa, and the Second Respondent, Mr Jose Diez, should be upheld or set aside. The applicants other than TCM are the remaining shareholders of TCM, namely Mr Andrea Cornelli, Mr Antonio (Tony) da Silva and the Iqbal Hassim Family Trust (the Trust) represented by its trustees, the fourth and fifth applicants. The Trust was the vehicle through which Mr Iqbal Hassim acquired shares in TCM.

[2] This judgment is regrettably lengthy, as was the trial before Boruchowitz J. To simplify reading I will refer to Mr de Sousa and Mr Diez jointly as the plaintiffs and to them individually as Luis and Jose, as was done at the trial. The present applicants will be referred to collectively as the defendants in relation to the proceedings in the high court and as the appellants in relation to the proceedings in this court. Individually, Messrs Cornelli, da Silva and Hassim will be referred to as Andrea, Tony and Iqbal. Three other individuals who feature in the narrative, Mr Wayne Impey, the Chief Financial Officer (CFO) of TCM and Messrs Frank and Fabio Cornelli, who were responsible for the operations of what is referred to as the Supplies Division of TCM, will be referred to as Wayne, Frank and Fabio. No disrespect is intended by the use of their given names without conventional honorifics. Conventional usage is adopted in relation to other individuals.

[3] In view of the range of issues that arise in this appeal and must be dealt with in the judgment it is convenient to preface it with an index. The issues are dealt with as follows:

Section Paragraphs

(a) Introduction 4 – 15

(b) Litigation history 16 – 27

(c) Preliminary issues (leave to appeal, joinder and

application for leave to intervene in the appeal). 28 – 40

(d) The pleaded case 41 – 50

(e) The evidence 51 – 74

(f) Section 252 75 – 114

(g) Luis’s claim of legitimate expectations and exclusion 115 – 152

(h) Luis’s dismissal 153 – 174

(i) Absence of genuine negotiations and a fair offer 175 – 188

(j) Loss of trust occasioned by a lack of probity 189 – 234

(k) Favourable treatment of Iqbal 235 – 241

(l) TCM’s payment of litigation costs 242 – 247

(m) Jose’s claim 248 – 250

(n) Conclusion on unfair prejudice 251 – 253

(o) The high court’s order 254 – 259

(p) Fair trial issues 260 – 270

(q) Costs 271 – 277

(r) Order 278

Introduction

[4] In the early 1980s, while they were training as customer engineers on the installation and repair of IBM computers, two young men, Luis and Andrea became good friends. They were good at their work, with Luis becoming a technical specialist and Andrea, who had a more commercial bent and was good with customers, becoming an operations specialist. In 1987, after IBM withdrew from South Africa, leaving their employer, ISM, as the sole agent for IBM products in South Africa, Andrea and Luis decided to set up in opposition to ISM providing computer repair services to IBM users. An accountant they approached for advice said that they should establish a company through which to operate the business. They did so and in due course that company became TCM. Although the initial plan had been for their line manager at ISM to join them, he withdrew at a late stage and TCM was incorporated with each of them owning 50% of the issued shares and each contributing their different skills to the venture.

[5] TCM was successful and expanded rapidly. Within a month or two of its establishment, Jose, also an IBM trained technician, was employed to work with Luis, and about two years later Tony, also formerly of IBM, was employed to work in sales with Andrea. Both Jose and Tony were promised shares in TCM, although the extent of the stakes they would receive was indeterminate and the promise was only given effect in 2004. Within a few years of its founding TCM had, through the acquisition of stakes in existing local businesses, established branches in Durban, Cape Town, East London (later moved to Port Elizabeth, as it was then known, now Gqeberha) and Bloemfontein. Under pressure from customers to extend the range of its services it also acquired 50% shareholdings in two existing companies providing software and network services. An increase in the number of employees accompanied the expansion and in 1990 an informal Board of Directors was constituted comprising Andrea as chair, Luis and representatives of the related companies as the remaining members. In truth this was merely a committee created to co-ordinate activities of the various companies involved in some way with TCM.1

[6] One of the ‘directors’ was Andrea’s brother, Frank. He did not work for TCM, but had his own company, Sternco (Pty) Ltd, which imported heavy duty machinery for large industrial corporations such as Iscor and was sharing TCM’s premises on an unexplained basis. He was Sternco’s representative on this board of directors. He became involved in TCM’s business because TCM needed to obtain items of IBM equipment and IBM spares from overseas. IBM disinvested from this country, along with other large multi-national corporations, as part of a campaign to place pressure on the apartheid regime. It appointed ISM as its sole South African representative. TCM could not source the equipment and spares it needed from either ISM, with which it was in competition, or directly from IBM. Apparently, Jose was able to identify and contact potential overseas suppliers, but TCM had no expertise in the process of collecting these items, arranging for their carriage by air or sea to South Africa, arranging insurance, freight and customs clearance and making payment through the international banking system. It turned to Sternco to undertake this work as an adjunct to the latter’s existing business. After Sternco was liquidated in about 1995, Frank and another brother, Fabio, continued to attend to the importation of equipment and spares for TCM, as well as continuing Sternco’s other business. This was done through the Supplies Division. It will be necessary to revert to the basis upon which this operated later in this judgment. For the present it suffices to introduce Frank and Fabio and the origin of their involvement with TCM.

[7] TCM’s business was successful and it expanded the scope of its operations. In addition to the branches it established service centres in 37 places in South Africa to enable it to respond rapidly to customer requests. This was important as major clients included a bank and a healthcare business whose activities extended beyond the major cities. According to its Annual Financial Statements (AFS), TCM earned annual revenues of R165 million in the 2002 financial year. In the following year that increased to R227 million. Andrea and Luis were the sole directors and their directors’ emoluments for those years, apart from any other benefits they may have enjoyed by way of salary, bonuses, allowances and the like, amounted to around R2.6 million, which they shared equally. Their roles within the company were reasonably well-defined. Andrea was effectively the chief executive and Luis headed up the technical side and the accounting. Jose was in charge of logistics and supplies and Tony’s role was in sales and marketing. These four were the key figures, although the staff complement had increased to several hundred.

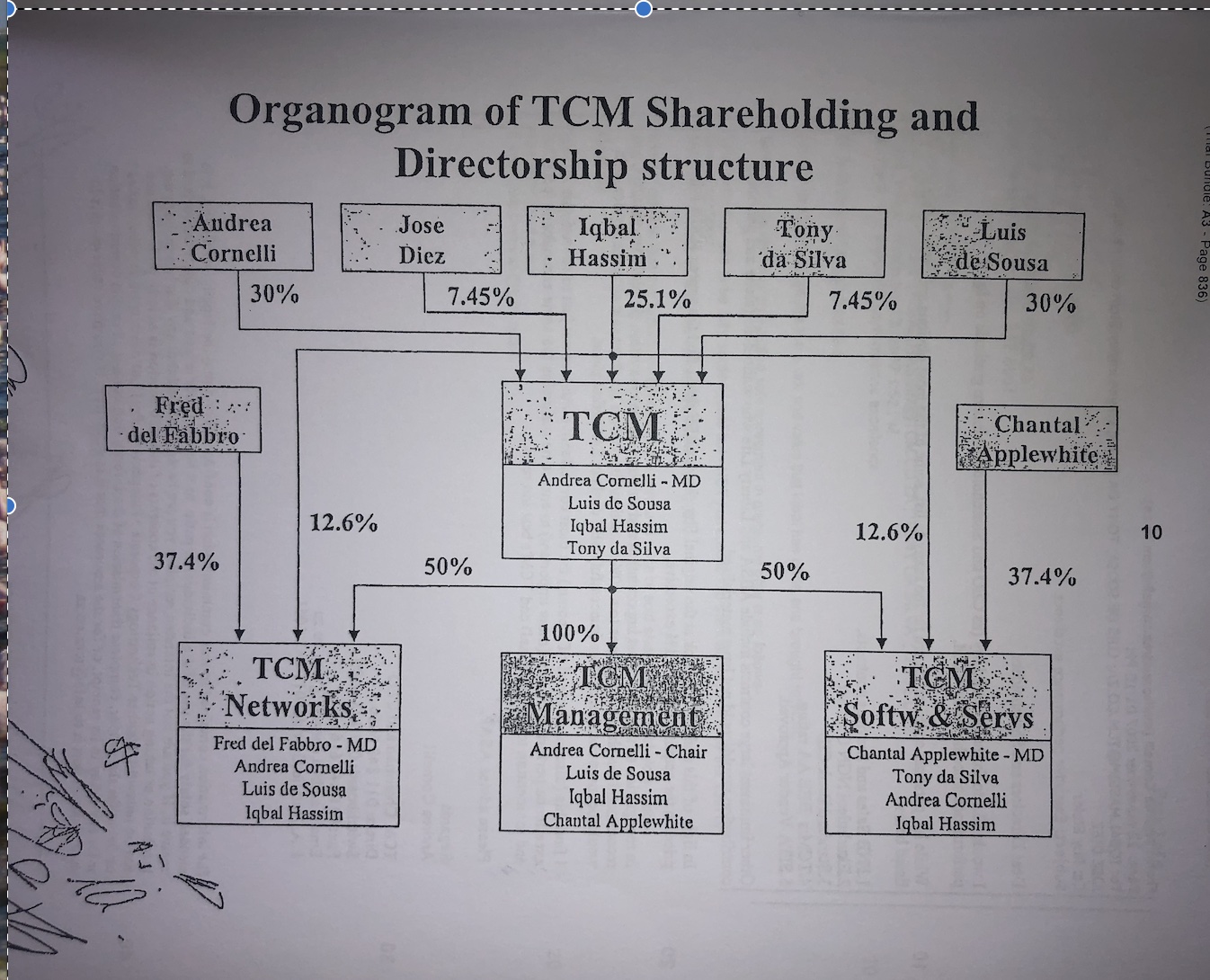

[8] In 2003, TCM lost a tender for a substantial contract with Standard Bank because it lacked an acceptable BEE profile. Andrea believed that, unless this was remedied, the future of the business was threatened and set about looking for a suitable person to introduce to the company to enhance its BEE profile to a suitable level. He identified Iqbal as being able to fill that role. Iqbal had a lengthy career with IBM and was at the time working for IBM in a senior position in Dubai. On 15 March 2004, heads of agreement were signed between Andrea, Luis, Tony, Jose, Iqbal and TCM, as well as the software and networks associated companies and the two outside shareholders, each of whom held a 50% share in those companies. The heads of agreement provided for the then existing shareholders of TCM, being Andrea and Luis (40% each) and Tony and Jose (10% each) to sell a total of 25.1% of the issued share capital in TCM to Iqbal. This would dilute Andrea and Luis’s stakes to 30% each and those of Tony and Jose to 7.45% each. In addition Iqbal was to acquire a 12.6% stake in the network and software companies at the expense of the two outside shareholders. Iqbal took up his position in TCM on 1 April 2004, after the signature of the heads of agreement, but before the conclusion of the formal sale and shareholders agreements that it contemplated. The sale of shares agreements was only concluded on 29 June 2005. Attached to the sale of shares agreement was the following organogram showing the corporate structure after implementing the transaction.

[9] The advent of Iqbal marked a distinct change in the internal dynamics of TCM and the commencement of the deterioration in the relationship between Luis and Andrea. In his founding affidavit in earlier application proceedings seeking similar relief in terms of s 252 of the Act (‘the s 252 application’), Luis said that from approximately 2007 the relationship between the members of TCM began to deteriorate. In evidence he tied this to certain events in November 2007. However, there were undoubtedly earlier signs of problems and particularly of a rift between Luis and Andrea. The earliest occurred in relation to two addenda to the sale of shares agreement in September 2005. Both dealt with the computation of the price. On 19 September 2005, Wayne, who had previously been TCM’s auditor and had been appointed as CFO and a director in 2004, brought them to Luis for signature. The two were related, because the one dealt with the computation of the purchase price in terms of the formula in the agreement and the other explained that the price had been computed on the basis of the division known as the TCM Supplies Division reflecting a nil value. Luis signed the first without demur. The second one he refused to sign, although Jose signed both. The treatment of the Supplies Division was one of the grounds upon which Luis and Jose claimed that they had suffered unfair prejudice. As foreshadowed in paragraph 6 it will be dealt with later.

[10] Another sign of problems was that, in the emails that were the principal means of communication among the executives, Luis increasingly questioned or challenged Andrea and the exchanges became personal and aggressive suggesting a breakdown in the relationship between the two men. An early exchange in January 2006 captures the tone of these communications. It started with Andrea receiving an email from IBM advising that there had been excellent feedback from the IBM compliance team regarding their performance on fourteen of TCM’s most profitable deals, resulting in a perfect IBM audit. The following morning he circulated the email to Luis, Iqbal and Tony with the suggestion that a staff member, Justine Impey, and her spouse, be awarded a company-paid overseas trip in appreciation of her contribution to the audit and asking for their approval or disapproval. Fourteen minutes after sending the email he received the terse response from Luis ‘Disagree.’ Not surprisingly he replied, asking: ‘Please provide brief motivation on why you disagree?’ The response was:2

‘I have been over this before and I don’t think that I have to do it again.

I guess this is a sort of democracy and majority wins. In a game there are always winners and losers. Fortunately for you have hand picked the other players and therefore we will never be playing on a level field. You sold it to me and I bought it. I’ll just have to live with it.’

[11] The original email distributing good news raised a simple issue that one would have thought could be resolved by way of a five minute conversation between individuals who had known one another and worked together amicably for years. Given the rather unpleasant tone of Luis’s response, it is no surprise that Andrea’s reply was equally sarcastic and reflected some frustration with Luis. It read:

‘I respect your views and decisions.

Its my (democratic) view that you are lacking in understanding of who/what contributes real value at TCM.

You references to I “sold you” I ‘hand picked” I created “unlevel playing field” is incorrect, disrespectful and indicative of your continual (democratic) lack of confidence and trust in my intentions and methods.

I’ve tried and will continue to better your understanding and confidence, all within reason and respect. I urge you be as respectful, co-operative and if possible less (pre) judgmental.”

The email ended with an invitation to discuss the issue or any other issue ‘in restoring your confidence and satisfaction in myself and/or TCM’. The contrast between the tone of this exchange and an earlier exchange of emails between the two men in 2002 was stark. Clearly something was going wrong well before the events of November 2007.

[12] The most cursory reading of the documents, the evidence and the record of the proceedings referred to below in the Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration (the CCMA), reveals that there was growing tension between Luis and Andrea. In November 2007 matters came to a head and Luis’s disgruntlement turned into action. He consulted attorneys and in May 2008, at their suggestion, approached Mr John Geel, an accountant with KPMG, to undertake a valuation of his shares. In his affidavit in the s 252 application he said that he did this because his and Jose’s positions were becoming untenable and that it would be in the best interests of all if they extricated themselves from the relationship. The terms of engagement of Mr Geel said that his task was ‘to assist Luis with an indicative value of the TCM Group to assist with possible future negotiations with prospective shareholders and/or investors’. As there was no question of any such negotiations occurring, the only purpose of the valuation was to be used in Luis’s efforts to extricate himself from the company by having the company, or the other shareholders, buy his shares. By then he and Jose, although the latter seems to have played a fairly passive role, had resolved to exit the company and were setting about achieving that aim.3 The relationship between him and Jose on the one hand and Andrea on the other, and Luis’s relationship with Iqbal, deteriorated. The record suggests that Andrea and the other directors were aware that Luis was engaged in consultations with legal and commercial advisers with a view to leaving the company.

[13] On 19 February 2009 a meeting was convened with Andrea at the instance of Luis and his advisers, Mr Geel and Mr Buchler, his attorney. Mr Geel testified that the purpose of the meeting was to put a proposal that would have involved the purchase of Luis’s and Jose’s shares in TCM. Initially it appeared that the parties would make progress because, Luis and Jose wished to sell and Andrea made it clear that he was desirous of seeing them exit the company. He said he would be more than happy to assist in a process over the next three months to make that happen ‘in good faith’. He put forward three criteria as indications of what he regarded as good faith. They were that Luis and Jose would reduce their involvement in the day-to-day operations of the company, take a reduction in salary and relinquish their executive directorships. There was then a caucus between the plaintiffs and their advisers. According to Mr Geel, on their return the response was that the conditions were unacceptable to Luis and Jose and:4

‘… at that point the meeting became acrimonious and I say acrimonious, was hostile, swearing, bad language in the meeting and Andrea said that was it, he got up, he stormed out, he left the meeting, gone.

The meeting then adjourned.

[14] The following day, Luis was suspended from his employment and presented with three disciplinary charges. An independent chair was appointed to deal with the disciplinary enquiry, which culminated in Luis being dismissed from his employ with TCM with effect from 31 March 2009. Luis appealed unsuccessfully to an independent appeal tribunal and, after that failed, he approached the CCMA. On 30 October 2010, after an eleven day hearing, the CCMA held that his dismissal was both substantively and procedurally fair and dismissed his claim based on unfair dismissal. He did not review that decision before the Labour Court. Instead he decided, in conjunction with his legal advisers, to concentrate his efforts on the s 252 application. That application had been launched on 28 September 2009 in parallel to the CCMA proceedings.5 In it he sought an order that either TCM, or Andrea, Tony and the Trust, purchase his and Jose’s shares in TCM for a price of R160 million or an amount to be determined. Jose was still employed when those proceedings commenced and was never dismissed, but resigned from his employment with TCM on 2 April 2013.

[15] The present action was instituted on 14 December 2010 before the s 252 application could be heard. It sought substantially the same relief on substantially the same grounds.6 After a trial lasting for 80 days that gave rise to the record of 17 438 pages now before us, Boruchowitz J upheld the plaintiffs’ claims and ordered TCM to purchase their shares at a value to be determined after consideration of a valuation of the shares by a referee. The judgment runs to 156 pages and 362 paragraphs. An application by the five applicants for leave to appeal was dismissed on 24 May 2017 and Andrea, Tony and the Trust were ordered to pay the costs on an attorney and client scale, including the costs of two counsel. On 7 September 2017 this court (Navsa ADP and Swain JA) referred their application for leave to appeal for oral argument in terms of s 17(2)(d) of the Superior Courts Act 10 of 2013, subject to the usual order that a full record be filed and that the parties be prepared, if called upon to do so, to argue the merits of the appeal. Given the size of the record and the scope of the appeal this Bench was specially constituted to hear the appeal before the commencement of the fourth term. We are indebted to counsel for their helpful submissions and their co-operation in enabling the appeal to be fully argued in the time available.

The litigation history

[16] I echo the words of Ponnan JA in Louw v Nel7 that this is a case that is by no means easy for an appellate court to deal with satisfactorily. That is not only because of the voluminous record and the confused presentation of the case and the defence, but also because time did not stand still while the litigation wended its way through the courts. The high court’s judgment contained an explanation of the history of the litigation. This contained very serious findings of bad faith against Andrea and stinging criticism of the conduct of the case by leading counsel for the defendants. These underpinned the making of punitive orders for costs against the defendants and necessitate a traverse of that history. Summons was issued on 14 December 2010. It was amended in 2012 to include reference to events after the issue of the summons. The trial was set down for hearing on 2 October 2012, but was adjourned because it could not be completed in the allocated time. The defendants, other than TCM, were ordered to pay those costs on the attorney and client scale, including the costs of two counsel and qualifying fees for an expert witness Professor Wainer. That order was made despite the fact that the defendants had wanted to proceed with the trial on the available dates, but objected to Professor Wainer giving evidence, because no expert notice had been delivered in respect of his evidence, nor had he attended any meeting of experts as required by the Gauteng Practice Manual. The order is challenged in this appeal.

[17] On 9 December 2013, shortly before the trial was due to recommence, having been set down for four weeks from 27 January 2014, the plaintiffs served a notice of intention to amend the particulars of claim to introduce additional financial material up to 2013 and the facts surrounding Jose’s resignation in 2013, together with an allegation amounting to a claim that he was constructively dismissed. The application to amend was opposed and then withdrawn on 16 January 2014, without a tender for costs. Leading counsel for the plaintiffs told the judge that they did not intend to adduce evidence outside the scope of the pleaded issues and that the evidence foreshadowed in the notice would be led ‘for corroborative and evidential’ reasons. The nature of these was not explained. He said in regard to the 2013 financial material that ‘we’re not complaining about 2013, we’re not extending the period of complaint’.

[18] In reality the evidence raised entirely new substantive issues that were not pleaded. Over the objections of the defendants’ counsel, Jose dealt with his treatment leading up to his resignation in 2013. The judge understood him to be claiming constructive dismissal and the heads of argument in this court contended that he was constructively dismissed. Professor Wainer dealt at length with the proper accounting treatment of maintenance spare parts. This was not referred to in the pleaded claim and only arose as a result of the revised expert report by Mr Geel produced in anticipation of the amendments to incorporate the 2013 material. In his earlier reports there was no reference to maintenance spare parts as a separate item. The defendants other than TCM were ordered to pay the costs of the plaintiffs’ application to amend on the attorney and client scale, including the costs of two counsel, even though the application was witdrawn. That order is also challenged in this appeal.

[19] When the trial commenced in January 2014 the respondents’ leading counsel delivered his opening address during the first two days and the applicants then applied for a separation of issues in terms of Rule 33(4). That consumed six days of hearing followed by a week’s adjournment during which the judge prepared a written judgment.8 The hearing of evidence commenced on 14 February 2014 with Mr Geel. A consolidated summary of his evidence had been delivered incorporating material up to 2013. Defendants’ counsel objected to the plaintiffs leading evidence in regard to events falling outside the times specified in the pleadings, being the matters raised in the withdrawn notice of amendment and derived from the consolidated report of Mr Geel. The objection was overruled and Mr Geel gave evidence for four days. The trial was then adjourned at the defendants’ request and cost.

[20] On 3 December 2014, during the adjournment, the defendants made an offer to purchase the plaintiffs’ shares for a price of R46 995 000 in the case of Luis and R7 097 000 in respect of Jose, supported by a valuation from TCM’s auditors, Grant Thornton. The offer was open for acceptance by either or both of Luis and Jose until 17 December 2014. On 5 December 2014 the plaintiffs’ attorneys wrote to the defendants’ attorney saying that the offer would be regarded as part of a genuine attempt at trying to resolve the matter, but that the deadline could not be met. The response was to extend it to 19 January 2015. The record contains no other response from the plaintiffs until a letter dated 12 February 2015, noting that the offer had lapsed, but indicating a willingness to engage in settlement negotiations. The defendants’ attorneys asked for a meeting, but nothing came of that.

[21] The hearing resumed on 5 May 2015. Notwithstanding that at the end of the previous hearing counsel had said that he had no further questions for Mr Geel, further evidence in chief was led from him dealing with facts about the performance of the company in 2014. These were derived from a fresh summary of Mr Geel’s evidence and a summary of Professor Wainer’s evidence. Leading counsel for the defendants noted an objection to this evidence being led but, given the previous ruling on the introduction of the 2013 evidence, merely so as to have it on record and without any expectation that the objection would be upheld.9 Mr Geel’s evidence in chief continued for a further day and a half. Thereafter his cross-examination commenced. It endured for eighteen days, with a good deal of time being lost due to interlocutory matters and discussions between counsel and the judge, primarily over the direction and duration of the cross-examination. Eventually on 1 June 2015, the judge directed that by midday the following day Mr Geel was to be ‘out of the witness box’. When midday came the following day there was a further debate about the duration of the cross-examination, but ultimately it concluded on 2 June 2015, subject to the reservation of a single issue.

[22] Luis’s evidence was led on four days thereafter. On 9 June 2015 the judge informed the parties that he had discussed the course of the case with the Judge President in the light of its length and the fact that he was due to retire from active service as a judge at the end of July 2016. An arrangement had been made for it to be set down for the whole of the first term of 2016. The Judge President had directed that:

‘Whether or not the matter is finalised at the end of the first term of 2016 the parties shall not be permitted to set down or enrol the matter for further hearing in this court. Judgment shall be delivered on the basis of the evidence which at that stage has been adduced. … The parties are directed to take all necessary steps in order to finalise the matter by not later than the last day of the first term of 2016.’

After this direction had been given Luis’s evidence continued for a further three days and the proceedings were then adjourned on 11 June 2015 to 25 January 2016.

[23] The trial resumed on that date, but the following five days were taken up with matters arising from an application by Luis under s 163 of the 2008 Act, aimed at compelling TCM to pay his costs of the litigation. TCM (but not the other defendants) opposed the s 163 application and, in the opposing affidavit, sought Boruchowitz J’s recusal from hearing that application, but not the trial. The grounds advanced were that in making the two earlier costs orders against the defendants other than TCM, he had expressed the view that TCM was an innocent and purely nominal party in the s 252 litigation and described the other four defendants as ‘wrongdoers’.10

[24] In December 2015 TCM had declared a dividend, but withheld Luis’s share because his by then divorced wife, Mrs Sharon de Sousa (now Mrs Oberem, the intervening applicant), claimed that one half of it be paid to her because a division of the joint estate formed part of the divorce order. TCM issued an interpleader summons and paid the money into its attorney’s trust account. This prompted Luis to add a further claim to his s 163 claim. This was to be paid the full amount of the dividend declared in December. When the trial resumed, a week was spent dealing with these matters including two days on the recusal application. On the morning that the parties were going to argue the s 163 application, an agreement was reached between Luis and Mrs Oberem, who had now applied to intervene in the trial, that the dividend could be paid and each would receive a portion of it. This resulted in the s 163 application not proceeding and the costs of the recusal application and the s 163 application were reserved. At the end of the trial the defendants, other than TCM, were ordered to pay the costs of both applications on the attorney and client scale, including the costs of two counsel. That order is also challenged in this appeal, in part on the grounds that only TCM was a party to those applications and not the other defendants. Andrea deposed to an affidavit confirming certain facts and specifically recorded that he otherwise abided the decision of the court on the merits. The other defendants did not oppose the application.

[25] When the matter resumed on 3 February 2016, Luis’s cross-examination started. It continued for nine days until 11 February 2016, when the judge made an order that:

‘Your cross-examination will cease tomorrow afternoon at 4 o’clock. You’re afforded another day to cross-examine Luis.’

The cross-examination ended the following day, although not without a protest being registered over its foreshortening. Luis was re-examined the following day and Jose then gave evidence. His evidence in chief took about a day and he was then cross-examined for about two days in all. When that was finished, plaintiffs’ counsel applied for, and after argument was granted, leave to recall Luis on certain stock sheets referred to in the cross-examination of Jose. That took the balance of that day and some of the following day.

[26] On 22 February 2016 Mr Geel’s cross-examination was resumed. He was re-examined on 24 February and then further cross-examined on 25 February 2016. Once he had completed his evidence Professor Wainer gave evidence and was cross-examined over three days before the plaintiffs’ evidence was concluded on 1 March 2016. The following day the defendants’ case was closed without calling any witnesses. Subsequently the parties addressed oral argument over five days and the judgment was delivered on 31 March 2017. Effectively the judge upheld every allegation made by the plaintiffs. His primary finding was that this was a small domestic company of the nature of a partnership and that the plaintiffs had been excluded from participation in its management in a manner that was unfairly prejudicial to them. In addition he held that there had been a failure to negotiate in good faith to enable the plaintiffs to exit the company and this failure on its own constituted further unfairly prejudicial conduct. He dealt with each of the other allegations in the particulars of claim and upheld all of them. His view was that these showed a lack of probity by Andrea in the conduct of the affairs of TCM that underlay the breakdown in relations between him and Luis and constituted a further ground of unfairly prejudicial conduct.

[27] In order to determine the appeals against certain costs orders as well as the fair trial issue it will be necessary to look in greater detail at some of the reasons for the protracted nature of the proceedings. An enormous amount of time was taken up by debates over interlocutory issues and procedural matters. At the outset, six days were devoted to arguing the application to separate the issues and the rest of the second week was spent in the preparation of a written judgment. Five days were spent over the s 163 application, the recusal and the related disputes. Time was repeatedly wasted over lengthy debates between the judge and counsel for the defendants, such as one that occurred on 23 February 2016. Mr Geel was about to be recalled to deal with one outstanding issue from his cross-examination and virtually a whole day was spent in debating whether he could deal in re-examination with some work he had done since his previous period in the witness box. The debate stretched over 118 pages of the record and took two-thirds of the day, while the re-examination took 143 pages and the further cross-examination it engendered 109 pages. That was a particularly flagrant example, but there were many others in the record. Throughout the trial the evidence was interspersed with regular exchanges between counsel and counsel, and the judge and counsel. These started with interruptions that became arguments and then wandered all over the terrain of the case without any apparent purpose. Time was taken up with repeated judicial warnings that the proceedings were becoming unduly protracted. The protests these engendered from leading counsel for the defendants – not counsel who appeared before us – further protracted the trial. None of this served to facilitate the smooth running of the case.

Preliminary issues

[28] The first issue is whether leave to appeal should be granted. If granted, the applicants raised two points in limine that it contended were dipositive of the appeal. The first was that the high court’s order did not include an order in terms of s 252(3) of the Act for the reduction of the share capital of the company in consequence of the order that the company buy the respondents’ shares. That was not a point in limine, but a possible flaw in the order granted by the high court and could only be properly considered at the end of the appeal. The second was that Mrs Oberem, should have been joined in the action after she divorced Luis on 26 October 2015. She had applied for leave to intervene in the trial, but her application had been dismissed and leave to appeal refused. Her further application to this court for leave to appeal was dealt with simultaneously with the application for leave to appeal in the present case. Orders referring each of them for oral argument were granted in similar terms on the same day, 7 September 2017. When Mrs Oberem’s application was heard a consent order was made in circumstances dealt with below. Nevertheless, on 20 October 2023, an application was delivered on her behalf for leave to intervene in this appeal if leave to appeal were to be granted. The second point in limine and the application to intervene in this appeal are intertwined and it is convenient to deal with them together.

Leave to appeal

[29] This case raised a number of points in regard to the proper approach to s 252 of the Act. While that section has now been repealed by the Companies Act 71 of 2008 (the 2008 Act), decisions on the earlier provision will be of assistance in relation to cases arising under s 163(1) of the new Act,11 which substantially re-enacts it.12 In addition the applicants have reasonable prospects of success if granted leave to appeal on the merits. Together those factors mean that leave to appeal must be granted.

[30] One further matter must be mentioned. The applicants raised a contention that they were denied a fair trial. Mr Green SC, who appeared before us on behalf of the applicants, but was not involved in the trial, raised the relevant points in appropriately moderate language by reference to passages in the record. For his part, Mr Subel SC, who appeared for the respondents at the trial and before us, said that ‘It was a thoroughly unpleasant trial.’ The record reveals some disconcerting exchanges between counsel and between leading counsel for the defendants and the judge. An application was made for the judge’s recusal in relation to an interlocutory application. The judgment is in parts couched in immoderate language when expressing displeasure with the manner in which the applicants’ defence to the claim was conducted. In refusing leave to appeal the judge recognised the serious nature of the allegations made in relation to his conduct during the trial, but characterised them as ‘nothing less than an abusive, derogatory, ad hominem attack on a presiding judge’. Regrettably, this conveyed that the judge was overly sensitive to the allegations and regarded them as a personal affront.13

[31] It is unfortunate that in the interests of justice the judge did not grant leave to appeal, so that an appeal court could express a view on the matters he described in these terms. He cited the following paragraph from the judgment of the Constitutional Court in Bernert v ABSA Bank:14

‘Apart from this the applicant has made serious allegations against judges of the Supreme Court of Appeal. These allegations concern the proper administration of justice. They strike at the very core of the judicial function, namely, to administer justice to all, impartially and without fear, favour or prejudice. Compliance with this requirement is fundamental to the judicial process and the proper administration of justice. This is so because it engenders public confidence in the judicial process, and public confidence in the judicial process is necessary for the preservation and maintenance of the rule of law. Bias in the judiciary undermines that confidence.’

[32] That is an important statement of principle, but the judge should have followed the guidance given in the following paragraph, which he did not quote, in regard to the desirability of such allegations being considered by a court that could investigate whether there was any substance in them. That paragraph reads:15

‘These are important constitutional issues that go beyond the interests of the parties to the dispute, for an independent and impartial judiciary is crucial to our constitutional democracy. It is, therefore, in the public interest that these issues be resolved. As these allegations are made against the Supreme Court of Appeal, there is no court that can investigate these issues other than this court. This court, as the ultimate guardian of the Constitution, has the duty to express the applicable law, in to enhance certainty among judicial officers, litigants and legal representatives, and, thereby, to contribute to public confidence in the administration of justice.’

In Bernert the Constitutional Court granted leave to appeal for those reasons without referring to the prospects of success, because the nature of the issues raised meant that it was in the interests of justice to do so. For the same reason leave to appeal should have been granted in this case in that this court could consider the complaint and address it to the extent necessary. Accordingly, leave to appeal will be granted.

Joinder and the application to intervene

[33] The circumstances in which Mrs Oberem applied to intervene in this appeal were set out earlier. The application was dealt with at the outset of the hearing and dismissed on the basis that reasons and appropriate costs orders would be given in this judgment. These are the reasons and they also dispose of the second point in limine.

[34] For reasons that do not concern us it was thought preferable for Mrs Oberem’s application for leave to appeal to be heard before the application in the present case. It came before this court on 27 May 2019. Mrs Oberem and Luis, together with Jose and TCM, arrived at a settlement that was embodied in a consent order. The relevant provisions of that order read as follows:

‘1 A Liquidator is appointed for the determination of the liabilities and assets of the former joint estate, of the Applicant [Mrs de Sousa] and the 1st Respondent [Luis]. In so far as is necessary the appointed liquidator is authorised to discharge all liabilities, liquidate and distribute all of the assets of the joint estate including the 30% shareholding in the 3rd Respondent currently registered in the name of the 3rd Respondent …

2 …

3 Subject to and once all the liabilities of the joint estate have been discharged, the extent of which shall be determined by the liquidator, the Applicant shall be entitled to be registered as a member of the 3rd Respondent as to 15% of its issued share capital, or such portion thereof as may remain thereafter after the discharge of the liabilities as aforesaid.

4 The 1st Respondent shall remain registered as to 30% of the share capital of the 3rd Respondent, until such time as the rights of the Applicant and the 1st Respondent in relation to such shares are finalised.

5 – 10 …

11 Nothing in this order shall affect the costs involved in the trial action under case 50723/2010 or in the appeal pending before the SCA. It is specifically recorded that the Applicant [Mrs Oberem] makes no admission as to any liability of the joint estate and of herself with regard to any costs relating to the trial action and/or any further proceedings relating thereto.’

[35] Mrs Oberem explained in her affidavit in support of the present application for leave to intervene that she had been advised that should leave to appeal be granted this court’s order established her direct legal interest in the present appeal. She believed that there was a conflict between that order and the high court’s order in the trial and that in view of the order in her appeal ‘it is no longer possible for this Honourable Court to uphold the judgment of Mr Justice Boruchowitz in respect of the main matter to the extent of my 15%, or to reverse or vary that order insofar as it may pertain to my 15%’.

[36] It was by no means clear what was sought to be achieved by the intervention if leave to appeal were to be granted to the Applicants and the appeal proceeded on its merits. If leave were refused, the high court’s order would remain in place unamended and would encompass what Mrs Oberem referred to as ‘my 15%’. If leave was granted, either the appeal would succeed, in which event the high court’s order would be set aside, or it would fail, in which event it would remain in place unamended. Either way the aim of protecting her 15% would not be achieved, at least not by way of some adaptation or amendment of the high court’s order.

[37] A more fundamental difficulty lay with the submission that the effect of the earlier order was to give Mrs Oberem a direct legal interest in the subject matter of the suit. In SA Riding for the Disabled Association16 the Constitutional Court said:

‘It is now settled that an applicant for intervention must meet the direct and substantial interest test in order to succeed. What constitutes a direct and substantial interest is the legal interest in the subject-matter of the case which could be prejudicially affected by the order of the court. This means that the applicant must show that it has a right adversely affected or likely to be affected by the sought.’

[38] Did the earlier order give Mrs Oberem a direct and substantial interest in the subject matter of this case? She clearly had no interest in whether the treatment of her former husband had been unfairly prejudicial, unjust or inequitable to him in his capacity as a 30% shareholder of TCM, or whether the company’s affairs were being conducted in a manner that was unfairly prejudicial, unjust or inequitable to him or some part of the members of the company. Her claim was dependent upon half of the shares registered in her husband’s name being hers (‘my 15%). She contended that this 15% shareholding ‘no longer forms part of the order’ of the high court and ‘this needs to be recognised at the commencement of the hearing of the appeal’.

[39] Unfortunately that was the same misconception that had underpinned her application to intervene at the trial,17 save that it was now thought to have been fortified by the consent order. Once the divorce order was granted Mrs Oberem acquired a right to a division of the joint estate, because it was property jointly owned by Luis and herself. In the ordinary run of cases this is done by agreement between the parties but, if they cannot agree, the court will either order a division, or appoint a liquidator to effect a division,18 or possibly both. The liquidator proceeds under the actio communi dividendo.19 All that is required is an equality of division in the end result, not a division of every asset, although where an asset is easily divisible the liquidator will ordinarily allocate it in equal shares to the former spouses. It is always open to them to agree that any particular asset be divided between them in this way once the liquidation process arrives at the stage where assets can be distributed. That is what occurred as a result of the settlement and the consent order granted by this court. The parties accepted that, once the liquidator’s work was done, the 30% shareholding, or some part of it, would still exist and could be divided equally between Luis and Mrs Oberem. To that end the consent order made provision for the company and the other shareholders to consent to this arrangement. It made no mention of the present proceedings or what would occur in respect of these shares if the high court’s order or the appeal against it was upheld. The parties knew that would be decided in this application. Prior to the liquidation of the joint estate, the order did not entitle Mrs Oberem to advance claims in respect of any portion of the 30% shareholding registered in Luis’s name. Nor did it give her a direct and substantial interest in the outcome of these proceedings. The 30% shareholding was to remain registered in Luis’s name until the position in relation to those shares was finalised. Until that occurred her interest in the shares themselves was no more than a spes. It is inconceivable that, without any express reference to it, the consent order altered the high court’s order in this case in the material respect suggested by Mrs Oberem.

[40] In the result the application to intervene was misconceived and Mrs Oberem lacked any direct and substantial interest in the litigation entitling her to be joined in the appeal if the application for leave were to be granted. As to costs, only the respondents sought an order for costs. In our view they were entitled to their costs, but only on the basis of one counsel and not on the basis of the costs being awarded on an attorney and client scale. That forms part of the order set out above.

The pleaded case

[41] In pleading the case, even though their situations were markedly different, no distinction was drawn between the position and complaints of Luis and those of Jose, save for a single paragraph dealing with the latter being sent to Namibia. Their cases overlap at some points but diverge at others. It is best therefore to separate the two.

Luis’s case

[42] The particulars of claim adopted a scattergun approach without clearly identifying the course of conduct of the company’s affairs of which complaint was made. Allegations were pleaded in the broadest possible terms with little particularity, such as the complaints about Luis being ‘criticised, belittled, humiliated and persecuted’, and descended to the trivial with an allegation that Andrea ‘unfairly and unjustly reduced the office and parking space available to’ Luis with a view to showing ‘public contempt’ for him and ‘denigrating his status as a founder member’ of the company. The friendship relationship on which the business had been established had plainly broken down, accompanied by a good deal of bitterness. The broad allegation was that Luis was entitled to the same standing and status in TCM as Andrea and the latter had set about a campaign to deprive him of that status and drive him out of the company.

[43] The extent to which the pleadings threw everything but the kitchen sink at Andrea is reflected in the reliance placed upon two events that, as a result of Luis’s opposition, did not occur. The first was a proposed amendment to the sale of shares agreement to reduce the price payable by Iqbal for the Trust’s shares. The second was a proposed loan to Iqbal to assist him to pay for the shares. Luis suggested that this might involve a contravention of s 38 of the Act. He refused to agree to the amendment and, irrespective of its lawfulness, the idea of a loan was dropped. The two paragraphs of the particulars of claim dealing with these matters commenced with the meaningless statements that Andrea ‘purported to compel the plaintiffs to conclude an amending agreement’ and ‘purported to procure that’ a contravention of s 38 would occur. Not only were they meaningless, but it is incomprehensible on what basis events that did not occur because of Luis’s opposition could constitute conduct by Andrea of the affairs of TCM in a manner that was unfairly prejudicial to Luis.

[44] Of more substance were allegations falling broadly into four categories. The most substantial related to Luis’s personal situation and encompassed his dismissal as an employee, his resulting exclusion from executive involvement in the day-to-day running of the business and the determination of bonuses and benefits in a manner that was said to be prejudicial to him and benefitted other executives and employees in return for their support of Andrea. It was alleged that Andrea had an ulterior motive of ‘humiliating, denigrating, and punishing’ the plaintiffs for not acceding to his demands. The second category related to allegedly favourable treatment of Iqbal directed at assisting him to pay for his shares by concluding retention agreements, making payments under those agreements and paying him enhanced bonuses and other benefits. The third category involved the accounting treatment of the Supplies Division, the alleged undervaluation of inventory and criticisms of the failure to control the operating expenses of the business, thereby diminishing the benefits flowing to shareholders and the value of the business. The fourth and last category related to the alleged failure in 2008 and 2009 to negotiate in good faith with Luis in order to enable him to dispose of his shares at fair value. Linked to that was a failure to furnish information and documents that would have enabled him to arrive at a fair value for his and Jose’s shares.

[45] I have endeavoured to place these disparate items in an appropriate order, although there was no discernible common thread binding them together. On that basis Luis’s case was the following:

(a) he had a legitimate expectation to daily involvement and engagement in the operations of the first defendant as a director and shareholder;

(b) more particularly he had a legitimate expectation to recognition and remuneration as (i) a founder member of TCM; (ii) a quasi-partner in the affairs of the business, which was a domestic company akin to a partnership; (iii) a participant in and contributor to the business of TCM of equal standing to Andrea; and to (iv) the due respect and regard of his fellow directors, shareholders and employees;

(c) since approximately 2007 these benefits had been denied to him;

(d) between 2007 and 2009 as a result of his unwillingness to agree to certain changes in the sale agreement under which Iqbal had acquired the shareholding in the company he placed in the Trust, he had been abused and treated in a demeaning manner; had his resignation as a director demanded; and had his bonuses reduced both in order to humiliate him and to use the funds to assist the Trust to pay for the shares and buy the personal loyalty of other recipients of bonuses;

(e) Andrea procured the conclusion of retention agreements with Iqbal that were a sham and benefited Iqbal and the Trust at the expense of the other shareholders;

(f) the disciplinary charges brought against him were spurious and in procuring them Andrea was driven by the ulterior motive of excluding him from the business;

(g) the disciplinary hearing was conducted in a manner that was unfair to him;

(h) during 2008 and 2009 Andrea refused to engage in bona fide discussions or negotiations aimed at permitting Luis to dispose of his shares either to the other shareholders or to a third party at a fair value and refused to permit him the proper access to documents and information to which he was entitled as a shareholder and director, thereby preventing him from arriving at a fair assessment of the value of his shares and complying with the provisions of the shareholders’ agreement in regard to the disposal of his shares;

(i) in three respects, Andrea engaged in conduct in regard to the finances of TCM that operated to the detriment of other shareholders, namely that he:

(1) caused the business of the Supplies Division of TCM to be transferred at no value to another company, TCM Printing Solutions (Pty) Ltd, owned by the Trust as to 25.1% and his brothers Frank and Fabio as to the balance in equal shares of 37.45% each; alternatively procured that the business of the Supplies Division was conducted and accounted for as if it were an entity separate from TCM, with all income and profits accruing for the benefit of the Trust and Frank and Fabio; and

(2) during the period 2008 and 2009 Andrea procured an under-valuation of the inventory of TCM of approximately R11.2 million for the purpose of reducing the value of the Luis’s shares; and

(3) from 2007 Andrea has conducted the business of TCM in a manner such that the operating profit had been drastically reduced; the operating expenses had almost doubled and, although the gross profit of the business climbed from R153 878 415 in 2008 to R228 746 081 in 2012, a failure to control the expenses of the business, resulted in the benefits available for distribution as dividends not accruing as they should and the growth and well-being of TCM not being properly ensured and protected;

(j) Andrea had authorised and procured that the funds of TCM be used to conduct the defence of the application proceedings referred to earlier in para 9 of this judgment;

(k) In the result the relationship of trust and respect between Luis and Jose on the one hand and their co-shareholders on the other had broken down so that it was impossible for them to co-operate meaningfully as shareholders, directors and employees and jointly to conduct the business of TCM and best advance its objectives.

Jose’s case

[46] Jose’s claims in regard to unfair prejudice could not be the same as those of Luis. TCM was established by Andrea and Luis. Jose and Tony had joined it as junior employees with an offer of an indeterminate number of shares. They had carried on as employees without that offer being fulfilled until shortly before it became necessary to sell shares to Iqbal as part of the BEE deal. At times Luis described them as directors, although they were not formally appointed as such until 2004. However, they appear from an early stage to have worked with Andrea and Luis as part of an informal executive committee for the business. They discussed major decisions, but the final decisions were taken by Andrea and Luis. On that basis it was alleged that Jose had a legitimate expectation of daily involvement in the operations of TCM and recognition of his status as a shareholder and director of the company. He did not claim to have been a ’quasi-partner’ as Luis did, nor did he claim to have the other expectations described above in para 45 (b) above.

[47] The allegations in the particulars of claim that were specific to Jose were that:

‘During the period of approximately September 2008 to the present time, the second defendant has:

16.1 marginalised, sterilised, humiliated and denigrated the status of the second plaintiff;

16.2 rusticated him to the first defendant’s Namibian office without discussion and without his consent;

16.3 threatened to dismiss the second plaintiff should he not resign as a director of the first defendant;

16.4 deprived the second plaintiff of his erstwhile duties and status without proper cause;

16.5 generally conducted himself towards the second plaintiff with the ulterior motive of forcing the second plaintiff to leave the employ of the first defendant and to give up his directorship thereof and/or his shareholding therein.’

It is unclear whether ‘the present time’ referred to in the preamble was 2010 when the summons was issued, or 2012 when the particulars of claim were amended, but on the facts alleged it does not appear to matter. In paragraph 17 it was alleged that the second defendant had conducted himself and the business of TCM in a manner calculated to deny and frustrate the plaintiffs’ legitimate expectation of their daily involvement and engagement in the operations of TCM and the recognition of their status as shareholders and directors.

[48] There was an overlap with Luis’s allegations in regard to the endeavour to reduce the price payable by Iqbal. Jose also objected to the retention payments to Iqbal and he adopted the allegations summarised in paragraphs 45 (i) to (k) arising from Mr Geel’s analysis of the financial position of the company. Like Luis he alleged that there were no bona fide negotiations over their possible departure from the company and the disposal of their shares. Nor was any reasonable offer made to purchase the shares.

The relief sought

[49] An order under s 252 is directed at remedying the unfair prejudice that has been suffered. The unfair prejudice on which the plaintiffs relied was the following.

(a) Their primary case was that by virtue of the nature of TCM’s business they both had a legitimate expectation to daily involvement and engagement in the business, as well as recognition of their status as shareholders and directors. In Luis’s case he claimed to be entitled in addition to recognition as an equal participant and contributor to Andrea. Both claimed to have been denied these rights from 2007 to 2010, when the summons was issued. They said that their prejudice was compounded by their being locked-in, causing an inability to dispose of their shares and realise their value. They sought a ‘buyout’ order that either TCM, or alternatively Andrea, Tony and the Trust, should purchase their shares and take transfer of them against payment of the sum of R160 million, or such other amount as the court might determine. They tendered against payment in full to resign as directors and sign all documents necessary to transfer the shares to whoever purchased them.

(b) The secondary case was that, even if they had no such legitimate expectations, Luis’s dismissal and the treatment Jose received before his resignation on 27 March 2013, were prejudicial to their position as shareholders and resulted in their exclusion from the daily involvement and engagement in the business and the recognition as shareholders and directors that they would otherwise have enjoyed. Like their primary case, the prejudice was compounded by their being locked-in.

(c) The third source of unfair prejudice was simply that they were locked in and, in and of itself, this constituted unfair prejudice to them as shareholders.

(d) Their final ground of unfair prejudice was that they had lost faith and confidence in the management of the business by Andrea and the other directors as a result of the latter conducting the affairs of the business in a manner lacking in probity, so that it was no longer possible for Luis and Jose to co-operate meaningfully with them in the conduct of the company’s business. They did not allege dishonesty or a general lack of probity in conducting the affairs of the company, but a lack of probity in relation to conduct directly affecting them. They attributed this to an intention to force them out of the company and compel them to sell their shares at less than their true worth. This unfair prejudice was closely linked to their being locked-in.

[50] Luis and Jose alleged in para 21 of the particulars of claim that the fair value of their shares was R160 million, alternatively an amount to be determined by the court. Mr Geel had determined that figure. Prior to the commencement of the hearing in 2014, the parties agreed that the issues to be decided would be as set out in the particulars of claim ‘save for paragraph 21 thereof, read together with paragraph 15 of the plea (“the remaining issues”) which relates to the quantum of the claim’. The precise effect of that separation of issues, like much else in the case, gave rise to an argument before us arising from the fact that the judgment ed TCM, rather than the other shareholders, to purchase the shares on the basis of a valuation to be done. That will be dealt with later in the judgment.

The evidence

Luis and Andrea

[51] It is a persistent judicial complaint that cases brought by minority shareholders claiming to have been unfairly prejudiced by the manner in which the affairs of the company have been conducted, come to resemble matrimonial suits and disputes over the dissolutions of partnership. The parties take the opportunity to unearth every grievance and canvas every disagreement, however minor, that might conceivably have led to the breakdown in their relationship. They pore over every actual or perceived fault or slight and blame one another for everything that went wrong.20 They frequently attribute to the other party improper motives directed at causing them harm. That occurred in the present case. Luis said that Andrea engaged in ‘a concerted and orchestrated plot to remove me from the business’. He accused Andrea and Iqbal of acting in concert in an attempt ‘to completely alienate me from the business’. According to him Andrea was acting mala fide and was motivated by ulterior motive and malice. Why he would have done this to an old friend and business partner was never explained. In his mind the incident that triggered the breakdown in the relationship occurred in November 2007 when Andrea asked for and received, over his strenuous opposition, an increase in his remuneration that meant that for the first time he earned more than Luis. He viewed this as a fundamental breach of an informal agreement they had concluded in about 1987 that they would always be on the same footing as far as remuneration and status was concerned.

[52] The rupture in regard to Andrea’s remuneration was followed two weeks later by Andrea attempting to persuade his fellow shareholders to reduce the price payable by Iqbal for the shares. Luis refused to accept that this was a genuine attempt to assist someone who had brought considerable benefits to the business, but needed assistance in meeting his obligations to pay the purchase price of the shares he had purchased. Instead he treated it as symptomatic of Andrea trying to secure the support of the other directors and senior executives to exclude him from the business. The final straw, after which the relationship between the two men came to resemble a form of internecine guerrilla warfare, was a dispute at the end of November and the beginning of December over Andrea’s attempt to sever the relationship between TCM and its Supplies Division by creating a new company in which the only shareholders would be his brothers Frank and Fabio with Iqbal as a BEE shareholder. This appears to have confirmed Luis’s belief that Andrea was actively working to bring about a situation where he was isolated as a director and would be excluded from the company. His resentment over what he perceived to be a humiliating downgrade in status was obvious and the source of many of the problems between the two of them.

[53] Luis attributed every disagreement between himself and Andrea from 2007 to a conspiracy to remove him from the company arising from ulterior motives and malice on the part of Andrea. Everyone who agreed with Andrea over the issues giving rise to disputes was tarred with the same brush of being part of a conspiracy, or having had their co-operation bought with generous bonuses and the like. Hard evidence of such conspiracies and ulterior motives was lacking. The company was thriving and growing to the benefit of all. Between 2004 and 2008 its value increased fourfold according to Luis’ evidence before the CCMA. Between 2008 and 2012, the date of the amended particulars of claim, its sales increased from R318 million to nearly R775 million. Its gross profit increased from R96 million to nearly R229 million. Its headcount grew from 396 to 534. Between June 2008 and July 2012 it paid out dividends of R81 million to its five shareholders, at a stage when dividends were not subject to income tax in the hands of the recipient. Insofar as relevant, that trend continued in the years after 2012. It is obvious that the business was thriving under Andrea’s leadership, notwithstanding Luis’s resistance. Prior to 2005 the company had not declared dividends. The new policy was adopted in the light of clause 4.3 of the sale of shares agreement, which provided that all dividends received by Iqbal would be used to discharge the purchase price of the shares. Luis was a major beneficiary of the new policy of paying substantial dividends.

[54] Beyond their increasingly divergent perspectives on their roles and relative positions in the company, no obvious reason emerged for the deterioration of the relationship between the two former friends. Every indication was that before 2004 and the introduction of Iqbal as a BEE shareholder the business was run very informally with Andrea in the CEO role taking responsibility for overall management and building up the company together with sales and marketing, and Luis in charge of the technical side of the business, logistics, procurement, inventory, some accounting record-keeping and administration. There was no evidence of there being any need to resolve issues, as each man took responsibility for his own area of work. Any problems were minor and resolved through informal meetings. After 2004, and especially after the conclusion of the shareholders agreement in 2005, Andrea took his role as CEO very seriously. He saw the loss of the Standard Bank contract and the need to address BEE issues as a wake-up call that the company needed to change and he set about addressing this. He identified Iqbal as the person who could address the BEE issue and make a contribution to the company and he appears to have conducted the negotiations with him with little input from anyone else. Luis did not ask for Iqbal’s CV or interview him.

[55] Luis repeatedly suggested that Andrea had persuaded him to go along with the BEE transaction and the shareholders agreement on the basis that nothing would change. This is difficult to believe and is contradicted by the existence and terms of the shareholders agreement. The very act of drawing up a shareholders agreement proclaimed that things would change and what had been an informal way of doing business would become more formal. Email exchanges and Luis’s evidence conveyed that he thought that Andrea had become over-infatuated with his role as CEO, wanted his own way in everything and resented any attempt to stand in his path. In other words he had grown too big for his boots. The shift in perceptions was well illustrated by the emails exchanged between them in November 2007 over Andrea’s suggestion that there be an adjustment to his own remuneration package.

[56] The exchange started with an email from Andrea to the directors saying that he had long thought that his package as CEO and Chairman was not consistent with his role and the performance of the company and suggesting an adjustment. Luis responded that afternoon saying that he could not approve of the recommendation and that he would send a note to the shareholders only. The note was in an email sent at the same time in which he said that directors’ increases, especially an increase for the CEO, should be approved only by the shareholders, He said that TCM’s net profits after tax were lower than the previous year although turnover was up by 20% and gross profit by 22%. He added:

‘4 On paper I believe that My Shareholding is worth less today than it was a year ago. Again I speak from what I can recall.

5 As a CEO he has not achieved the number one goal. That is to create fair value in the Shares held by Shareholders.’

Luis added that one cannot compare the package of the CEO of a private company, especially if the CEO is a major shareholder, with that of a public company, as the risks were different. However, he said he respected Andrea’s ability as a businessman and his ability to maximise profits and most aspects of his vision for the group. Accordingly he said he would accept an increase of 5% to bring his total increase for the year up to approximately 18%.

[57] The tone of the email, the criticism directed at him and the grudging offer of an insignificant increase, angered Andrea. He responded as follows:

‘Hi Luis,

I find your views mostly irrelevant and emotional. Your personal (non appreciative) views are very evident and consistent with your general conduct and behaviour.

For the record this is not an “increase” its an “adjustment” long overdue (many years ago), often recommended by other shareholder/directors, yet always opposed by you, maybe thinking and acting as a joint CEO? I remind you, you are not a Joint CEO or a 50/50 partner in a small business (as once was, a long time ago). Accepting, acknowledging this may resolve the continual non-productive baggage you keep raising.

I need not (further) justify the and my CEO role, responsibility, value, performance or shareholder returns over the last 20 year … most evident in the last 3 years.’

Andrea went on to say that the directors represented the shareholders and were accordingly able to contribute and vote on the matter he had raised. He claimed that the amount of the adjustment was not material to him as he was not seeking wealth through his salary, presumably in contrast to seeking wealth from his shareholding. He said he was willing to embrace any CEO better suited to the job than he and suggested that Luis nominate one. The issue carried on over the next couple of days with the exchanges becoming increasingly sarcastic on both sides. It included further criticism by Luis of the company’s performance and Andrea’s response that he had addressed these issues ‘enough”.

[58] The one point of substance that emerged from these exchanges was that Luis was hoping for the company to list on the JSE to enable the shareholders to realise the true potential of their shares. Andrea recognised that Luis was looking for an ‘exit strategy/plan’ and asked that there should be no more JSE meetings. He suggested that Luis should see whether he could get an offer for the company without its key people and told him that he was ‘a fine one judging the CEO performance’. An article about earnings for CEO’s and executive directors was attached, and he added sarcastically:

Now ask yourself how come “you” earn the same as the CEO … maybe its because you have the same size office?’