12

IN THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA

GAUTENG DIVISION, PRETORIA

CASE NO: 38549/2022

(1) REPORTABLE: NO (2) OF INTEREST TO OTHER JUDGES: NO (3) REVISED: YES ___________________________ _______________________ DATE SIGNATURE

In the matter between:

SPAREPRO (PTY) LTD Applicant

and

THE NATIONAL REGULATOR FOR COMPULSORY First Respondent

SPECIFICATIONS

THE SOUTH AFRICAN NATIONAL ACCREDITATION Second Respondent

SYSTEM

G.U.D HOLDINGS (PTY) LTD Third Respondent

t/a ECE 90 BRAKE TESTING

___________________________________________________________________

JUDGMENT

___________________________________________________________________

NEUKIRCHER J:

1] This is in essence an application to review and set aside a Directive issued by the first respondent1 under s15(3) of the National Regulator for Compulsory Specifications Act 5 of 2002 (NRCS Act) in June 2022. The applicant (Sparepro) also seeks certain further relief flowing from the provisions of the NRCS Act.

THE PARTIES

2] Sparepro is an importer and distributor of aftermarket automotive components for passenger and light commercial vehicles in Sub-Saharan Africa.

3] The Regulator is established under the NRCS Act and its function is to “provide for the administration and maintenance of compulsory specifications in the interest of public safety and health or for the environmental protection; and to provide for the matters connected therewith”2

4] In terms of s5 of the NRCS Act, the object of the Regulator is inter alia, to administer, maintain and enforce compliance with compulsory specifications3 and it achieves this by, inter alia, entering into agreements with conformity assessment services providers to inspect, examine, test or analyse samples on its behalf. The NRCS must, by virtue of VC 8053 and its conformity assessment policy, only rely on evidence relating to conformity with compulsory specifications where that evidence is provided by a laboratory that:

a) is a member of an international or regional mutual acceptance scheme;

b) has been successfully assessed against the requirements of ISO/IEC 17025 by SANAS or an ILAC affiliated accreditation body; or

c) has been accredited to ISO/IEC 17025 by SANAS or an ILAC affiliated accreditation body.

5] The third respondent (GUD) is just such a service provider and was appointed by the Regulator in compliance with its obligations under section 5 of the NRCS Act. In fact, at a time the SABS was also accredited as was a laboratory known as ABTI.

6] It bears mentioning that GUD is Sparepro’s competitor in the automotive spare parts component market.

7] This application pertains specifically to brake pads and whether that part, sold by Sparepro, complies with SANS 20900: 20104. According to the parties, in order to test these parts, the company’s testing facility must be ISO77025: 2017 accredited.

8] According to GUD5, it tests its own “safeline” brake pads to ensure compliance with the SANS Standard and it also purchases brake pads of competitors sold in the South African market and tests those to ensure that they comply with SANS standard. Thus, pursuant to this policy of theirs, GUD purchased “from dealers” sets of the Kratex brake pads sold by Sparepro in early 2021, subjected them to testing at the GUD facility6 and “found them to be sub-standard”.

9] As a consequence, the Technical Director of GUD - Mr Avilan Reddy (Mr Reddy) - then lodged a complaint with the Regulator on 12 March 2021. The Regulator was then required to initiate a bidding process to appoint a service provider to conduct the necessary tests, and issued a request for quotations (RFQ) on 21 July 2021.

10] According to the Regulator, the only quotation received was from GUD. In fact, interestingly enough, Mr Reddy submitted the quote on behalf of GUD. But the Regulator’s argument is disingenuous7 as:

a) the RFQ was not sent to ABTI who was an accredited service provider at the time;

b) the service level agreement between the SABS and the NRCS had expired by July 2021 and had not yet been renewed and it was thus excluded from the bidding process;

c) the only other accredited company was GUD.

11] The Regulator argued that although the RFQ was not sent to ABTI in July 2021 it made no difference as ABTI’s accreditation lapsed in December 2021 anyway. But what that argument ignores is that when the RFQ was sent out in July 2021, and an award made soon after, ABTI was accredited and yet inexplicably excluded from the bid process.

12] On 13 April 2021, prior to the RFQ being sent out, the NRCS conducted an inspection at Sparepro’s Johannesburg premises and removed 5 sets of Kratex brake pad parts B1-548. On 30 August 2021, 31 August 2021 and 1 September 2021, the Regulator toured “and assessed” the ECE909 testing laboratory on the dates the B1-54 parts were tested, and witnessed the testing and thus they say that they “mitigated against potential concerns which could arise in relation to ECE 90’s position as both an accredited tester and an entity related to a competitor of Sparepro.”

13] Interestingly enough, it is common cause both on the papers and during argument, that at this time the Regulator had refused to disclose the identity of the complainant to Sparepro. The Regulator persisted with this position and provided only a redacted copy of the complaint in the Rule 53 record and in the response to Sparepro’s Rule 35(12) notice10. This is despite the fact that GUD disclosed the origin of the complaint as far back as 24 October 2022 ie some 7 months earlier. GUD also provided an unredacted copy of the complaint in their Rule 31(12) response on 1 June 2023. Given this, the position held by the Regulator is not acceptable.

14] This, of course, must be viewed in the context of the Regulator’s position on the one hand that everything was above-board and transparent, and Sparepro’s argument on the other hand, that the process was tainted by bias.

15] Thus, it was only in October 2022 that Sparepro became aware that GUD had lodged the complaint and that despite this, the Regulator appointed it to conduct the tests.

16] It is common cause that Sparepro’s parts failed these tests. The test report, dated 6 September 2021, was signed by the very same Mr Reddy.

17] On 7 September 2021, the applicant was informed of the outcome of the tests conducted on the B1-54 brake pads and asked for a re-test to be conducted. The Regulator consented subject to 3 conditions:

a) that a re-test would have to be at Sparepro’s expense;

b) the Regulator would have to be present; and

c) Sparepro could only use the samples in the Regulator’s possession for re-testing.

18] But the next Sparepro knew, and before a final agreement was reached, the Regulator issued a directive in terms of s15(1)11 of the NRCS Act these being Directive ADD 41220 (issued on 7 September 2021).

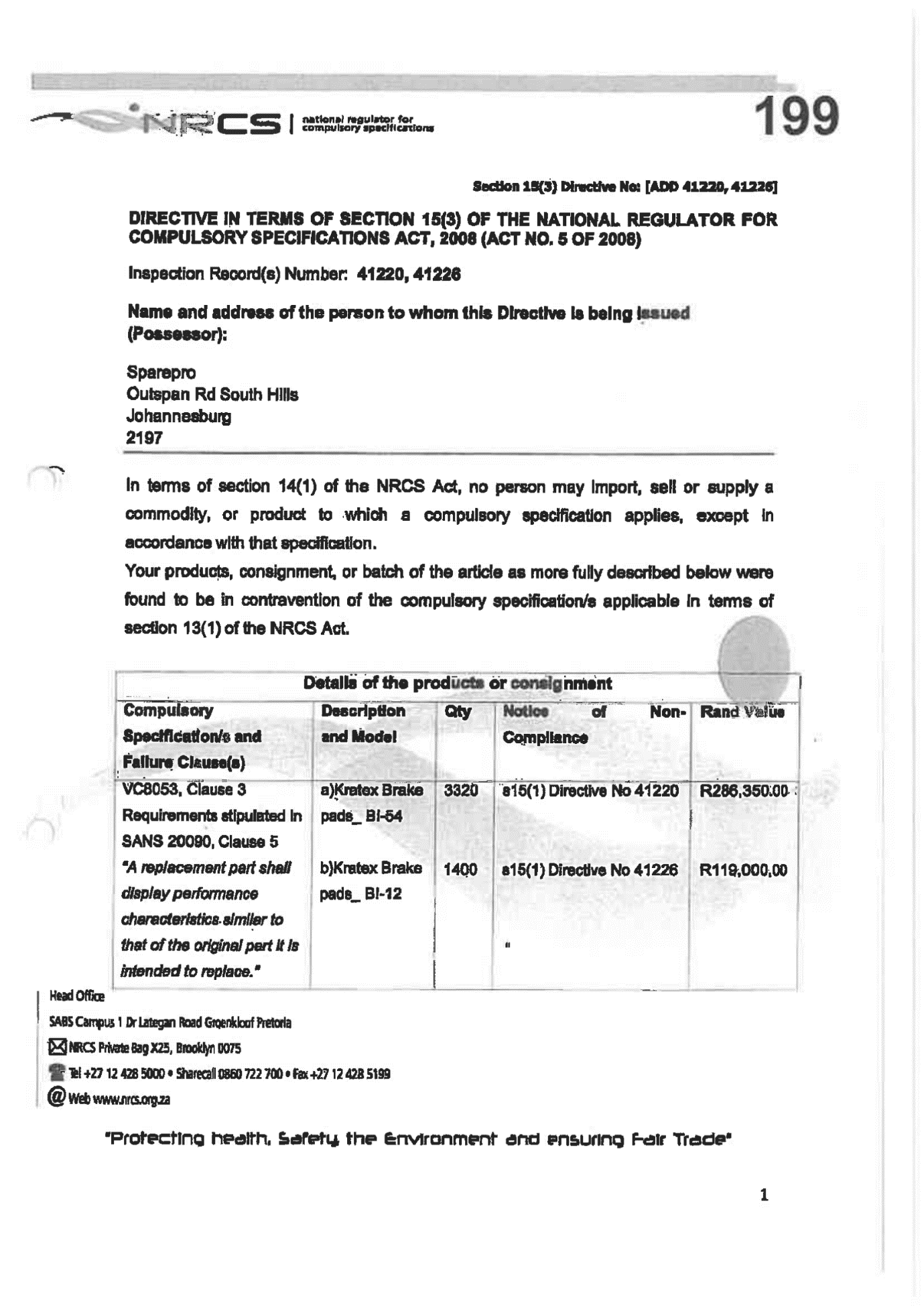

19] Directive No ADD 41220 indicates, inter alia, the following:

a) that the B1-54 brake pads had failed the hot and cold compressibility test and were therefore not in compliance with VC 805-3.

b) that Sparepro was to retain possession and control of its 3320 units of B1-54 brake pads12;

c) Sparepro was directed not to tamper with or dispose of any of the products until the directive was withdrawn by the NRCS in writing.

20] On 7 September 2021 the NRCS Inspectors also requested 5 samples of brake pads, the first being B1-12 (D3015) suitable for Toyota Hiace vehicles, and the second being B1-38 (D3295) suitable for VW Golf 4 vehicles, but refused to divulge the identity of the complainant. These brake pads were tested and the test report - dated 15 September 2021 - indicates that they too failed. These reports are also signed by Mr Reddy.

21] On 17 September 2021 a further s15(1) Directive No ADD 41226 was issued to Sparepro, the terms of which are identical to that of Directive No ADD 41220. This time, the 1400 units of the B1-12 brake pads are valued at R119 000-00.

22] Both Directives provide that Sparepro must provide the Regulator with a proposed corrective action plan in writing13 within 7 business days.

23] During all this, Sparepro and the Regulator were discussing the proposed re-testing of all the seized brake pads, which Sparepro informed the Regulator was necessary before it could submit any corrective action plan. On 12 October 2021, Sparepro was informed that official feedback would be given in regards to the re-testing, however on 22 October 2021 the Regulator again demanded a corrective plan vis-à-vis Directives 41220 and 41266. Between 9 and 18 November 2021 the Regulator issued s15(1) Directives to Sparepro’s customers as its stance was that Sparepro had failed to submit the required corrective action plan (my emphasis). However, these were not confined to the B1-54, B1-12 and B1-38 brake pads: they pertained to all Kratex brake pads sold by Sparepro.

24] Bearing in mind that Sparepro was, as yet, still in the dark about the identity of the complainant14, on 29 November 2021, Sparepro provided the Regulator with its corrective action plan which included a plan for the re-testing to be done locally by ECE 90 as there was no other local suitably accredited testing facility, but under certain conditions

“81. On 29 November 2021, Sparepro (via its then attorneys) furnished the National Regulator with its CAP ... The CAP included provision (under paragraph 17) for the re-testing of the allegedly non-compliant parts. Sparepro reluctantly accepted in this regard that re-testing could only be done locally by ECE 90, given SANAS' inability to recommend a suitable alternative accredited testing facility, though it was still concerned about the conflict of interest inherent in this.”

25] As a result of the conflict of interest concerns, Sparepro’s conditions were, inter alia, that:

a) ECE 90 must advise Sparepro when the equipment that would be used for the re-tests was last calibrated and provide Sparepro with the equipment’s calibration;

b) in advance of the re-tests being conducted, the NRCS inspectors may attend Sparepro's warehouse and select new samples of part nos. Bl-54; Bl-12 and Bl-38 from any of Sparepro's warehouse stock, to be used for the re-tests (the samples). The samples must be securely sealed, and must only be opened when it is time for each of the respective re-tests;

c) representatives of Sparepro must accompany the samples with the NRCS inspectors to the ECE90 Brake Testing facility on the day that the tests were to be conducted;

d) the sealed samples must only be opened in the presence of both the NRCS Inspectors and Sparepro representatives at the time that each respective re-test is to be conducted;

e) both the NRCS inspectors and the Sparepro representatives must be present, at all times, when the re-testing is being conducted on each of the samples, and Sparepro must be allowed, at the testing facility, to inspect the samples and take pictures of each of the samples immediately after each re-test is complete;

f) the results of the re-tests must be compared to the previous test reports of ECE90 brake testing and in the event that the samples pass the re-tests, Sparepro will request that the Directives ADD41220 and ADD41226, and all other directives that were issued to Sparepro's customers, be forthwith withdrawn.

26] The Regulator was amenable to the conditions save that the tests would have to be conducted on the products in its possession. For reasons not relevant hereto, the next communication between it and Sparepro was in April 2022 and by that time Sparepro was represented by new attorneys of record who informed the Regulator that:

a) the NRCS should allow Sparepro's products to be tested by a different laboratory or service provider to ECE90 given ECE90's obvious conflict of interest, and that Sparepro was in the process of engaging with another testing facility in order for the brake pads to be tested at Sparepro's expense.

b) it was unlawful for the National Regulator to issue directives to customers which were unrelated to parts numbers Bl-12, Bl-38 and BI-54;

c) although Sparepro continued to dispute the test results from ECE90, given that there are no alternative service providers in South Africa to conduct the relevant tests, and in the light of the costs of conducting tests overseas, Sparepro was, on advice, considering whether to have the remaining batches of brake pad part numbers BI-12, Bl-38 and Bl-54 surrendered to the NRCS, as per note 3 of the Directives, which it is assumed would result in those Directives being withdrawn and;

d) in the meantime, the brake pads with the numbers BI-12, Bl-38 and Bl-54 were being kept at the warehouse of Sparepro stipulated in the relevant Directives, and would remain there, in the possession and under the control of Sparepro, until the directives are withdrawn.

27] By early June 2022, the parties had reached an impasse and the Regulator then issued its s15(3) Directive on 7 June 2022 and sent it to Sparepro on 8 June 2022. It states:

28] The Regulator states that the s15(3) Directive was the result of an informed decision after:

a) it had become aware of the fact that Sparepro had, in contravention of the s15(1) Directives, continued to sell Kratex brake pads;

b) at a subsequent inspection15 at Sparepro’s premises it discovered that the products had been moved in contravention of the s15(1) Directives;

c) Sparepro employees refused to co-operate with the Regulator’s Inspectors at an inspection conducted at its warehouse on 29 April 2022;

d) through its new attorney, Sparepro reneged on or repudiated the agreement reached during late 2021.

29] During 2021 Sparepro applied to the Regulator for the renewal of its letters of authority (LoA). The Regulator sent it an invoice on 31 January 2021 for the renewal fee which Sparepro then paid, but the Regulator refused to issue the new LoA ostensibly because of Sparepro’s non-compliance with its s15(3) Directive and its failure to file a corrective action plan.

THE REVIEW

30] The review grounds are based on the following:

a) that the s15(3) Directive was not authorised by the empowering provisions;

b) that it was procedurally unfair;

c) that it was vitiated by bias or a reasonable perception thereof.

THE SECTION 15(3) DIRECTIVE IS NOT AUTHORISED

31] The argument is grounded in the provisions of s15(1) and s15(3) of the NRCS Act itself. These must be read in conjunction with the provisions of Regulation 7 issued under s36 of the NRCS Act16. The relevant provisions are the following:

a) s15(1) states:

“If the Chief Executive Officer on reasonable grounds suspects that a commodity or product, or a consignment or batch of a commodity or product, does not conform to or has not been manufactured in accordance with a compulsory specification that applies to it, the Chief Executive Officer may issue a directive to ensure that any person who is in possession or control of the commodity or product, consignment or batch, keeps it in his or her possession or under his or her control at or on any premises specified in the directive, and does not tamper with or dispose of it, until the directive is withdrawn by the Chief Executive Officer in writing.”

b) S15(3) states:

“If the National Regulator finds that a commodity or product referred to in subsection (1) does not conform to the compulsory specification concerned, the National Regulator may

(a) take action to ensure the recall of a commodity or product;

(b) direct in writing that the importer of the consignment returns it to its country of origin; or

(c) direct in writing that the consignment or batch of the article concerned be confiscated, destroyed or dealt with in such other manner as the National Regulator may consider fit.”

c) Regulation 7 states:

7. (1)(a) A directive issued by the CEO in terms of section 15(1) of the Act, shall be withdrawn in writing by the CEO if no steps have been taken by the Board in terms of sections 15(3) or 34(4) of the Act within 120 days from the date of issue of the directive by the CEO.

32] Thus, a s15(1) Directive rests on a suspicion “on reasonable grounds” that the product to which it relates does not comply with the specifications that apply to it.

33] From this point on, and in accordance with Regulation 7, the Regulator has 120 days within which to issue a s15(3) Directive. If it fails to act within this period, the s15(1) Directive “shall be17 withdrawn in writing by the CEO”. The reason for this is clear: a s15(1) Directive affects the business and standing of the entity or person – it relates to a recall of the product which has financial implications and insofar it is directed to a customer of that person/entity, it affects its business and business reputation in that industry. Thus, any compliance issue must be dealt with expeditiously.

34] It is common cause that the s15(1) Directives were issued on 7 September 202118 and 17 September 202119. Thus, in relation of Directive No ADD 41220, a s15(3) Directive had to be issued on or before 7 January 2022; and in relation of Directive No ADD 41226 on or before 17 January 2022. It is common cause too, that the s15(3) Directive was issued on 8 June 2022 ie 5 months after the 120 days period had passed.

35] Mr Ngcongo argued that this was permissible given the fact that the parties had been in discussion since September 2021 - but this argument ignores 2 facts:

a) that the NRCS Act and Regulations do not give the Regulator any discretion to extend the time period set out therein – in my view the reason is obvious: it is to minimise the prejudice caused to a party in Sparepro’s position and prevent compliance issues from being dragged out endlessly;

b) no correspondence was placed before the court demonstrating that the parties had agreed to hold over any s15(3) Directive pending the finalisation of their discussions.

36] Thus the Regulator acted ultra vires in issuing the s15(3) Directive.

37] Furthermore, s15(4) requires the NRCS to inform the Minister of Trade and Industry of the s15(3) Directive within 21 days – it failed to do so, and there is no indication on these papers that it complied with s15(4) at any stage, in fact the Regulator has conceded that it did not.

38] Neither party took issue with the fact that the decision to issue the s15(3) Directive constitutes an ‘administrative action’ in terms of the Promotion of Administrative Justice Act 3 of 2000 (PAJA) and thus is capable of review under PAJA.

39] Section 6(2)(b) of PAJA provides:

“(2) A court or tribunal has the power to judicially review an administrative action if -

…

(b) a mandatory and material procedure or condition prescribed by an empowering provision was not complied with.”

40] Given the Regulator’s failure to comply with the 120 day period prescribed in s15(1) as read with Regulation 7, and its failure to comply with s15(4), in my view the decision falls to be reviewed and set aside in terms of s6(2)(b) of PAJA.

41] But even if I am wrong on this aspect, the s15(3) Directive falls to be reviewed and set aside in terms of s6(2)(c) of PAJA which provides:

“(2) A court or tribunal has the power to judicially review an administrative action if –

…

(c) the action was procedurally unfair”

42] The unfairness arises from the fact that Sparepro firstly was not given any opportunity to make representations as to why the s15(3) Directive should follow the s15(1) Directives; and secondly, irrespective of this, they were never notified of the nature or purpose of the s15(3) Directive.

43] Insofar as Sparepro argued that it was never notified that a s15(3) Directive may follow the s15(1) Directive, this leg of the argument must fail: the s15(1) Directive itself provides for such a possibility.

44] However, that Sparepro was not given any opportunity to make representations before the s15(3) Directive was issued, is so. In fact, it would appear that the s15(3) Directive was the Regulator’s reaction to its failed inspection at Sparepro’s warehouse on 20 April 2022.

45] Given that by June 2022, when the s15(3) Directive was issued, the Regulator was 5 months late already there is no reason for it not to have complied with s3(2)(b) of PAJA20 and invited Sparepro to make comments or submissions. A failure to do so has seen such a decision declared invalid21.

46] Thus, I agree that the s15(3) Directive was procedurally unfair.

47] The last ground pertained to the issue of bias and this relates to the direct hand GUD had in the events leading up to the issue of the s15(3) Directive. The uncontroverted facts are that:

a) GUD initiated both complaints;

b) the complaints led to the Regulator sending out a RFQ;

c) in essence the Regulator sent out the quote to only one of the two accredited laboratories at the time: ABTI was not sent the RFQ - this was conceded during argument;

d) the only response to the RFQ was from GUD and not just from GUD, but from the very same person who had initiated the complaints - Mr Reddy;

e) the results of the tests conducted by GUD were then signed off by the very same Mr Reddy;

f) on the strength of these the Regulator then issued the two s15(1) Directives.

48] The test for bias, formulated in President of the Republic of South Africa v South African Rugby Football Union22, is whether a reasonable, objective and informed person would on the facts reasonably comprehend that the decision maker would not bring an impartial mind to bear on the adjudication of the case. It stands to reason that no-one can be the judge in his or her own matter23.

49] Section 6(2)(a)(iii) of PAJA provides:

“(2) A court or tribunal has the power to judicially review an administrative action if—

(a) the administrator who took it—

…

(iii) was biased or reasonably suspected of bias”

50] Thus, an administrative action tainted with bias will be reviewed and set aside24.

51] In this matter GUD is simply an extension of the Regulator: one cannot lose sight of the fact that the tests conducted by GUD were not preparatory in nature but instead formed part of the adjudicative function of the Regulator and were instrumental in the Regulator’s decision-making process. It is clear that in this entire chain of events, GUD became the judge and jury and the Regulator the executioner and thus on this ground too, the review must succeed and the s15(3) Directive set aside.

RE THE S15(1) DIRECTIVES

52] Sparepro seeks in its Amended Notice of Motion the following relief:

“Directing that the Chief Executive Officer of the First Respondent (“NRCS”) withdraw Directive No. ADD 41220, issued in terms of section 15(1) of the National Regulator for Compulsory Specifications, Act 5 of 2008 (the “NRCS Act”) on 7 September 2021, and Directive No. ADD 41226, issued under section 15(1) of the NRCS Act on 17 September 2021 (the “section 15(1) Directives”), in terms of regulation 7(1)(a) of the Regulation promulgated in terms of the NRCS Act”.

53] The relief is based on the fact that both s15(1) Directives have reached the maximum period of validity and the s15(3) Directive was not issued within the 120-day period set out in Regulation 7. Therefore, they must be withdrawn and insofar as the CEO has failed to comply with s15(1), this court is empowered to issue the sought declarator.

AD LETTER OF AUTHORITY

54] The Regulator argued that the LoA was not issued because of Sparepro’s failure to comply with the s15(1) Directives and because Sparepro had failed to address its concerns.

55] However, Sparepro’s LoA expired in January 2022 and it filed for renewal prior to that. By this time the relevant time period provided for in Regulation 7 had expired and the CEO was obliged to withdraw the s15(1) Directives. Furthermore, the Regulator had provided Sparepro with an invoice, which it then paid. All of this being so, there was no basis upon which the Regulator could refuse to issue the LoA.

56] In any event, the Regulator conceded in argument that should I set aside the s15(3) Directive, there would be no basis upon which this relief could be refused.

THE RETURN OF SEIZED GOODS

57] Prayer 7 of the Amended Notice of Motion reads:

“Directing the NRCS to return to the applicant the Kratex brake pads seized and confiscated from the applicant’s clients’ premises;”

Given that this is a consequence of the withdrawal of the s15(1) Directives, this relief would follow.

FURTHER RELIEF

58] The parties were ad item that the only relevant relief was that contained in Prayers 1, (excluding A and 1B), 2, 6 and 7. The remainder of the relief in the Amended Notice of Motion was not persisted with.

COSTS

59] The matter is of importance to both parties. The Regulator argued that the guidelines established in this matter were of importance to establish the proper and efficient way it would regulate its duties going forward. The matter is also relatively complex and the papers voluminous. Both parties were represented by 2 counsel who each sought costs on Scale C. I agree that the scale is commensurate with all these factors.

ORDER

60] The order is the following:

1) The Section 15(3) Directive No. [ADD 41220, 41226] (the “Section 15(3) Directive”), issued by the First Respondent (the “NRCS”) by email on 8 June 2022 is reviewed and set aside.

2) The Chief Executive Officer of the First Respondent (“NRCS”) is directed to withdraw Directive No. ADD 41220, issued in terms of section 15(1) of the National Regulator for Compulsory Specifications, Act 5 of 2008 (the “NRCS Act”) on 7 September 2021, as well as Directive No. ADD 41226, issued under section 15(1) of the NRCS Act on 17 September 2021 (the “section 15(1) Directives”), in terms of regulation 7(1)(a) of the Regulation promulgated in terms of the NRCS Act.

3) The NRCS’s refusal to issue the applicant with letters of authority (“LOAs”) is reviewed and set aside and the NRCS is directed to issue the Applicant with the relevant Letter of Authority.

4) The NRCS is directed to return to the applicant the Kratex brake pads seized and confiscated from the applicant’s clients’ premises.

5) The first respondent is ordered to pay the applicant’s costs, including the costs of the 2 counsel of which one is Senior Counsel, on scale C.

___________________________

NEUKIRCHER J

JUDGE OF THE HIGH COURT

GAUTENG DIVISION, PRETORIA

Delivered: This judgment was prepared and authored by the Judge whose name is reflected and is handed down electronically by circulation to the parties/their legal representatives by email and by uploading it to the electronic file of this matter on CaseLines. The date for hand-down is deemed to be 4 June 2024

For the Applicant : Adv P Farlam SC with Adv V Mabuza

Instructed by : Edward Nathan Sonnenbergs Inc

For the First Respondent : Adv P Ngcongo with Adv J Mthembu

Instructed by : GMI Attorneys

For the Second Respondent : No appearance

and Third Respondent

Matter heard on : 7 May 2024

Judgment date : 4 June 2024

1 The National Regulator for Compulsory Specifications (the Regulator).

2 NRCS Act – preamble.

3 Section 5(1)(b) and (d)

4 “the SANS Standard”

5 Which filed an explanatory affidavit but does not oppose this application.

6 The ECE90 testing laboratory

7 As not only was GUD’s quote submitted to the Regulator by Mr Reddy, but GUD’s appointment letter was received by Mr Reddy,

8 These had formed the subject matter of the complaint.

9 Which is the division within which GUD Holdings conducts the tests

10 Which is dated 22 May 2023

11 “15 (1) If the Chief Executive Officer on reasonable grounds suspects that a commodity or product, or a consignment or batch of a commodity or product, does not conform to or has not been manufactured in accordance with a compulsory specification that applies to it, the Chief Executive Officer may issue a directive to ensure that any person who is in possession or control of the commodity or product, consignment or batch, keeps it in his or her possession or under his or her control at or on any premises specified in the directive, and does not tamper with or dispose of it, until the directive is withdrawn by the Chief Executive Officer in writing.”

12 Valued at R286 350-00

13 For the correction of the production in order to bring them in line with the relative compulsory specification.

14 Although it suspected that it was GUD

15 What it terms an “intelligence gathering exercise”

16 GG No 33615 of 15 October 2010

17 My emphasis

18 Directive No 41220

19 Directive 41226

20 “3(2)(b) In order to give effect to the right to procedurally fair administrative action, an administrator, subject to subsection (4), must give a person referred to in subsection (1) -

(i) adequate notice of the nature and purpose of the proposed administrative action;

(ii) a reasonable opportunity to make representations;

(iii) a clear statement of the administrative action;

(iv) adequate notice of any right of review or internal appeal, where applicable; and

(v) adequate notice of the right to request reasons in terms of section 5.”

21 Mamabolo v Rustenburg Regional Local Council 2001 (1) SA 135 (SCA) at par [20]; Fidelity ADT (Pty) Ltd v Mongwe NO and Others (45583/2019) [2022] ZAGPPHC 605 (8 August 2022)

22 1999 (4) SA 147 (CC) at para [148]

23 Nemo iudex in sua causa; Basson v Associated Portfolio Solutions (Pty) Ltd and Others (16224/2017) [2018] ZAWCHC 184 (14 December 2018)

24 Tshwane City v Link Africa (Pty) Ltd and Others 2015 (6) SA 440 (CC) at para [45]

Cited documents 4

Judgment 2

Legislation 2

| 1. | Promotion of Administrative Justice Act, 2000 | 2250 citations |

| 2. | National Regulator for Compulsory Specifications Act, 2008 | 170 citations |