CHAPTER 1: DEFINITIONS, INTERPRETATION AND OBJECTS OF THE ACT

Section 1: Definitions

Several concepts are defined in sec 1, including:

-

Abuse of vulnerability1

-

Body part

-

Carrier

-

Debt bondage

-

Electronic communications

-

Exploitation2

-

Forced Labour3

-

Forced marriage4

-

Immediate family member

-

Letter of recognition

-

Removal of body parts5

-

Servitude6

-

Sexual exploitation7

-

Slavery8

-

Trafficking in persons

-

Victim of trafficking (distinguish between child and adult victims)

Section 2: Interpretation of certain expressions

(1) “person has knowledge of a fact if…”

(2) “person ought reasonably to have known or suspected a fact if…”

(3) “any act includes an omission”

Section 3: Objects of Act

The key international TIP obligations (4P approach) to combat trafficking holistically includes:

-

Prosecution and punishment of human trafficking,

-

Protection and assistance provisions for victims of trafficking;

-

Prevention measures;

-

Partnership/cooperation measures.9

The objects of this Act seek to comply with these obligations in international agreements10 by providing for the

-

Prosecution of trafficking offences and for appropriate penalties,

(including effective enforcement measures);

-

Prevention of trafficking

-

Protection of and assistance/services to victims of trafficking;

-

co-ordinated combating of trafficking through co-ordinated implementation, application

and administration of the Act (including the drafting of the national policy framework).11

CHAPTER 2 OFFENCES, PENALTIES AND EXTRA-TERRITORIAL JURISDICTION

Section 4: Trafficking in persons

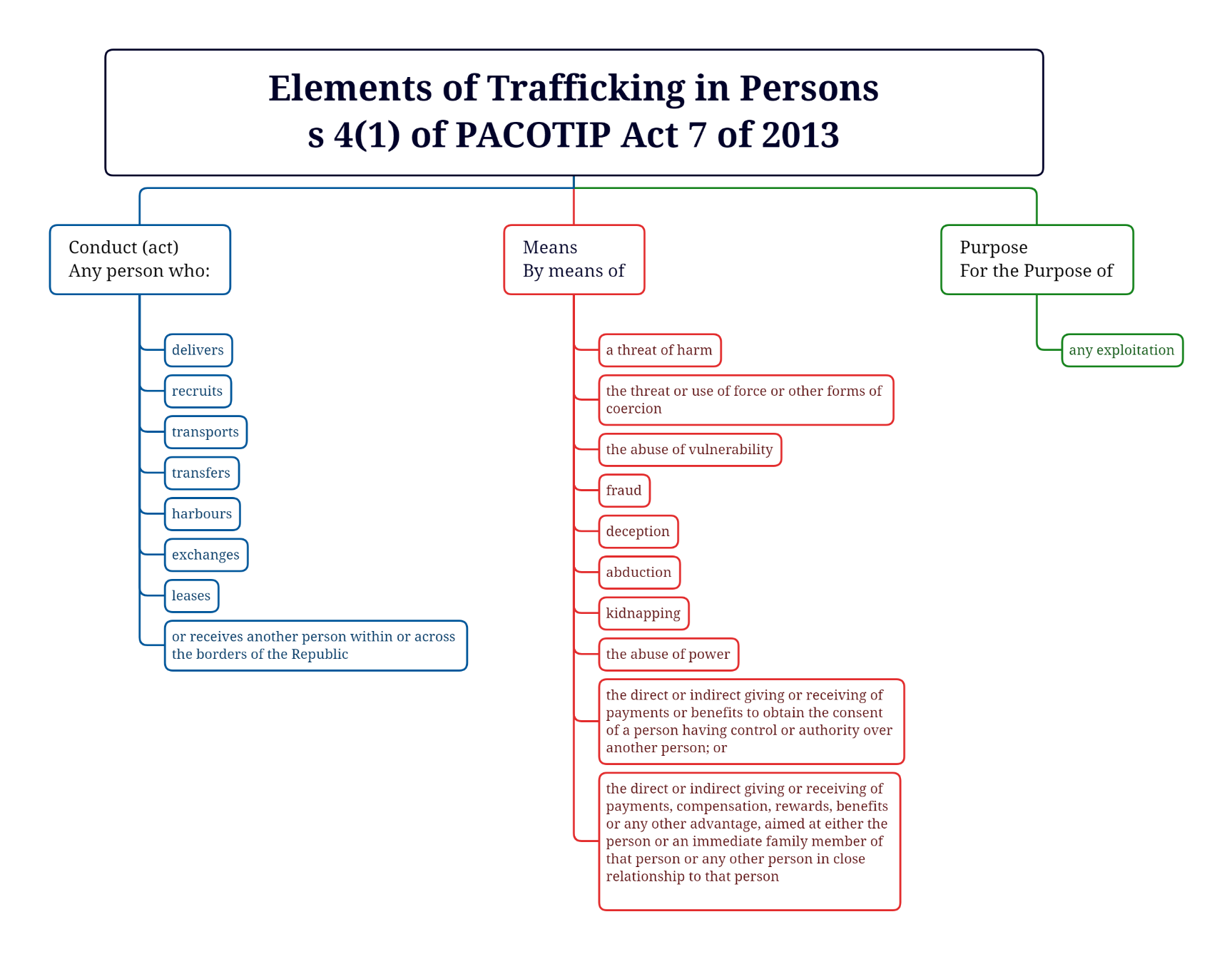

The PACOTIP Act criminalises all types of human trafficking, irrespective of the age or gender of the victim.12 In line with the standard for the first internationally agreed-upon definition of human trafficking,13 the definition of ‘trafficking in persons’ (TIP)14 in section 4(1) of the PACOTIP Act 7 of 2013 comprises three main components, namely the:

|

conduct (action) |

what is done? |

|

means |

how is it done? |

|

exploitative purpose |

why is it done? |

|

|

|

|

A conviction on TIP requires that the state proves beyond reasonable doubt the elements of the crime in terms of section 4(1) of the PACOTIP Act 7/2013, namely that the perpetrator

|

|

|

|

|

The PACOTIP ACT does not specifically prescribe the elements of child trafficking. 16 The Trafficking Protocol (article 3(c)) waives the means element of the human trafficking definition when a child is trafficked. Thus only the prohibited act and the exploitative purpose are required to constitute child trafficking in international law. 17 It is recommended that the PACOTIP Act be interpreted in line with the Protocol’s definition for child trafficking. 18 |

Conduct element

The PACOTIP Act prohibits 9 acts, but none of them is defined in the Act.19 Guidelines for the interpretation of some of the concepts in the Trafficking Protocol’s definition of ‘trafficking in persons’ are provided in the Legislative guide of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) of 2020.20

The term “recruit” refers in general to “the act of drawing a person into a process and can involve a multitude of methods, including orally, through advertisements, or online through the internet. In transnational cases, recruitment can involve activities in the country of origin, of transit or of destination, for example, involving legal or semi-legal private recruitment agencies.”21

‘Transportation’ (movement of the victim) is not a mandatory requirement.

‘Transportation’ (movement of the victim) is not a mandatory requirement.

The ‘transportation’ (or transfer) of a victim, one of the 9 possible acts prohibited in section 4(1), is not mandatory to constitute the human trafficking offence.22 The prohibited acts are substitutes or alternatives to one another - proof of any one of them constitutes the required conduct element. Similar to article 3(a) of the Trafficking Protocol, these acts are therefore disjunctive. “It is not an essential requirement of trafficking in persons that the victim be physically moved.”23

The difference between ‘transportation’ and ‘transfer’:

“93. “Transportation” would cover the acts by a carrier by land, sea, or air by any means or

kind of transportation. Transportation may occur over short or long distances, within one

country or across national borders.

94. “Transfer”, too, can refer to transportation of a person but can also mean the handing over of effective control over a person to another. This is particularly important in certain cultural environments where control over individuals (mostly family members) may be transferred to other people.”24

“’Harbouring’ may be understood differently in different jurisdictions and may refer, for instance, to accommodating a person at the point of departure, transit, or destination, before or at the place of exploitation, or it may refer to steps taken to conceal a person’s whereabouts. 44 Harbouring can also be understood to mean holding a person.

“Receipt” of a person is the correlative of “transfer” and may refer to the arrival of the person, the meeting of a person at an agreed place, or the gaining of control over a person. It can also include receiving persons into employment or for the purposes of employment, including forced labour.45 Receipt can also apply to situations in which there was no preceding process, such as inter-generational bonded labour or where a working environment changes from acceptable to coercively exploitative.”25

Means element

The PACOTIP Act prohibits 10 possible means to accomplish the conduct element.26 “These means describe various ways in which perpetrators exercise control over or manipulate their victims.”27 Guidelines for the interpretation of some of the listed means are provided in the Legislative guide of the UNODC(2020).28

(a) a threat of harm;

(b) the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion;

Force is usually easily identified. The concepts ‘threats’ and ‘harm” are not defined in the PACITIP Act, but it is submitted that these concepts relate to physical, psychological, emotional or economic outcomes.29 The concept ‘coercion’ refers to unjustified demands such as extortion and is “an umbrella term that encompasses the use of physical or psychological pressure, force or threat thereof.”30

(c) the abuse of vulnerability;31

Traffickers often administer drugs to their victims to “form addiction and perpetually depend on

traffickers who provide the drugs. In the long term, drug dependency becomes an effective

means of control and perpetuation of exploitation of victims.”32

The PACOTIP Act defines the concept ‘abuse of vulnerability’ as any abuse that leads a person to believe that he or she has no reasonable alternative but to submit to exploitation. In short, abuse of a position of vulnerability occurs when the perpetrator intentionally takes advantage of a person’s personal, situational or circumstantial vulnerability. Therefore, two components must be proven, namely

-

the victim is in a position of vulnerability and

-

the perpetrator abuses this vulnerability.

Vulnerability is assessed by taking into consideration the following circumstances of the alleged victim:33

-

Personal vulnerability: e.g. age (youth or old age), gender, pregnancy, physical or mental disability, dependency cultivated through drug or other substance addiction,34 romantic or emotional attachment, bound by cultural or religious practices e.g juju oaths.

-

Situational vulnerability: e.g. irregular status: being irregularly in a foreign country in which he or she is socially, culturally or linguistically isolated.

-

Circumstantial vulnerability: e.g. unemployment, social, cultural or economic circumstances.

Such vulnerabilities may be pre-existing or created by the trafficker. Section 1 of the PACOTIP Act lists:

-

pre-existing vulnerabilities, such as a person being illegally in the country, pregnancy, (physical or mental35) disability, being a child36 and social or economic circumstances; as well as

-

vulnerability created by the perpetrator, such as addiction to depending-producing substances.37

(d) fraud;

(e) deception;

While fraud is a recognised common-law crime in South African law, deception is not. Although a perpetrator, who misleads another person by means of a lie, may not comply with all the elements of fraud,38 such deception still qualifies as a ‘means’ element in terms of the PACOTIP Act. “In the context of trafficking in persons, fraud and deception frequently involve misrepresentations as to the nature of the job for which victims of trafficking are recruited, the location of jobs, their end employer, living and working conditions, the legal status in destination countries, and the travel conditions, among other things. In many cases, fraud and deception are used in conjunction with threats, violence, or coercive practices.”39 Van der Watt40 reports that in S v Seleso the accused “deceived and lured the 16-year-old victim to South Africa from Lesotho with promises of furthering her education during October 2015. The accused sexually exploited the victim for monetary reward and kept the proceeds.”

(f) abduction;

(g) kidnapping;

In South African law abduction and kidnapping are recognised as independent, separate crimes.

While kidnapping is mainly a crime against freedom of movement, common-law abduction protects parents’ rights to exercise factual control over their unmarried minor children and to consent to such children’s marriage.41

(h) the abuse of power;

This means is often present in situations where the perpetrator has power over another person based on their relationship (e.g. parent and child, pastor and congregation members, employer and employee, principal/teacher and student, coach and sportsperson or prison guard and an inmate.42

(i) the direct or indirect giving or receiving of payments or benefits to obtain the consent of a person having control or authority over another person; or

(j) the direct or indirect giving or receiving of payments, compensation, rewards, benefits or any other advantage, aimed at either the person or an immediate family member of that person or any other person in close relationship to that person,

The means listed in section 4(1)(i) is similar to the Protocol in that it provides for the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to obtain the consent of certain persons. However, section 4(1)(j) broadens the scope of the means element by providing for the ‘giving or receiving of payments…or any other advantage’ without requiring it to be made to a specific person or for a specific purpose. Thus, it is submitted that the means listed in (j) are broad enough to incorporate (i) and that the latter is therefore redundant.43

Traffickers use reprisals against the victims' families and loved ones as one of the main methods to control their victims.44 Therefore, after listing the prohibited means, the PACOTIP Act provides that the threat, force, harm or any of the other means may be directed to the trafficked victim (or his/her property) or a third party, namely an immediate family member45 or a person in close relationship to the victim. “For example, a person may be “recruited” as a result of a threat of violence to their family member. The recruiter may also tell the victim they will disclose private information to the victim’s family or community if they fail to comply with their demand that they come with them. That is true, mutatis mutandis, of almost all the various means listed.”46

Traffickers use reprisals against the victims' families and loved ones as one of the main methods to control their victims.44 Therefore, after listing the prohibited means, the PACOTIP Act provides that the threat, force, harm or any of the other means may be directed to the trafficked victim (or his/her property) or a third party, namely an immediate family member45 or a person in close relationship to the victim. “For example, a person may be “recruited” as a result of a threat of violence to their family member. The recruiter may also tell the victim they will disclose private information to the victim’s family or community if they fail to comply with their demand that they come with them. That is true, mutatis mutandis, of almost all the various means listed.”46

Purpose element

The third integral element of trafficking in persons entails that the prohibited act is done for

the purpose of any form of exploitation.47 According to the UNODC48 the phrase “for the

purpose of” indicates that:

-

the required fault element is intention;49

-

the accused committed the prohibited act with the intention to exploit the victim himself or herself or while knowing (or foreseeing) that the victim will be exploited by another;

-

the accused need not be the person who exploits the victim;

-

the actual exploitation of the victim is not required - committing the prohibited act with an exploitative purpose suffices for a conviction on human trafficking.50

‘Exploitation’ is not defined in the PACOTIP Act.

Section 1 of the Act does not define the concept of ‘exploitation’, but states that exploitation “includes, but is not limited to “a non-exhaustive list of practices that constitutes exploitation.51 This formulation allows for the inclusion of other forms of existing exploitation,52 but also of future forms of exploitation.53 While this broad formulation of exploitation is meaningful, the exploitative purpose “can be difficult to establish and can manifest itself in different ways. Therefore, there is a need for flexibility in determining what constitutes exploitation. At the same time, clear parameters need to be established in order to uphold the principle of legality and to also ensure that criminal law responses to human trafficking are focussed on sufficiently serious behaviour.”54

Section 1 of the PACOTIP Act lists the following examples of ‘exploitation’:

(a) all forms of slavery or practices similar to slavery;

Case law:

A conviction on human trafficking for these forms of exploitation could not be traced yet in South African case law.

The Act’s definition of “slavery”, namely reducing a person by any means to a state of submitting to the control of another person as if that other person were the owner of that person, is similar but not identical to the definition in the Convention to Suppress the Slave Trade and Slavery of 1926.55

“Practices similar to slavery” is not defined in the Act nor international law. However, article 1 of the Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade, and Institutions and Practices Similar to Slavery lists four “institutions and practices similar to slavery”, namely:

-

Debt bondage:56 the condition arising from a pledge by a debtor of his personal services or those of a person under his control as security for a debt, if the value of those services as reasonably assessed is not applied towards the liquidation of the debt or the length and nature of those services are not respectively limited and defined;

-

Serfdom: the condition of a tenant who is by law, custom or agreement bound to live and labour on land belonging to another person and to render certain services to such other person, whether for reward or not, and is not free to change his [or her] status;

-

Servile forms of marriage, any practice whereby

-

A person, without the right to refuse, is given in marriage on payment of money or in-kind to her family; or

-

The spouse (or family) has the right to transfer the other spouse to another person for value received or otherwise; or

-

A person on the death of the other spouse is liable to be inherited by another person;

-

-

Any practice whereby a child under the age of 18 years is delivered by the natural parents, whether for reward, the exploitation of the child or the child’s labour.57

(b) sexual exploitation;

Case law:

Multiple convictions on sex trafficking of adult women and girl children have been reported in South African case law.58

While “sexual exploitation” is not defined in other international instruments,59 the Act’s definition is broad and based on the South African context, namely the commission of any sexual offence referred to in the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences and Related Matters) Amendment Act (SORMA Act) or any offence of a sexual nature in any other law ( e.g. Sexual Offences Act 23/1957, etc)

(c) servitude;

Case law:

A conviction on human trafficking for this form of exploitation could not be traced yet in South African case law.

“Servitude” is not defined in international law,60 but in section 1 the term is defined as “a condition in which the labour or services of a person are provided or obtained

-

through threats of harm to that person or another person, or

-

through any scheme, plan or pattern intended to cause the person to believe that, if the person does not perform the labour or services in question, that person or another person would suffer harm.”

(d) forced labour;

*Case law:

Convictions on adult labour trafficking could not be traced yet in South African case law.

The definition of ‘forced labour’ in section 1 contains three components:

-

Obtaining or maintaining labour or services of any person

-

without his/her consent61

-

through threats, use of force, intimidation, other coercion or physical restraint to that person or another person. 62

(e) child labour

*Case law:

Cases of trafficking for child labour have been reported in South African case law.63

The concept “child labour” is defined in section 1 of the Children’s Act 38 of 2005 and means work by a child which-

-

is exploitative, hazardous or otherwise inappropriate for a person of that age; and

-

places at risk the child's well-being, education, physical or mental health, or spiritual, moral, emotional or social development.

(f) the removal of body parts

*Case law:

A conviction on human trafficking for this form of exploitation could not be traced yet in South African case law.64

The inclusion of this form of exploitation covers scenarios where “a person is exploited for the purposes of obtaining profit in the ‘organ market’ and for the removal of organs and/or body parts for purposes of witchcraft and traditional medicine.”65 The removal of body parts is not inherently exploitative for it may be lawful depending on the circumstances and purpose (e.g. for legitimate medical reasons) of such removal.66 Therefore, the definition of “removal of body parts” in section 1 requires the removal or trade in any body part in contravention of any law. Examples of such unlawful removal may include “where victims are coerced into entering an arrangement to sell their organs. Alternatively, victims may be deceived about the benefit or compensation they will receive, or they may not be fully informed about the procedures and health consequences of organ removal. Another method involves luring the donor abroad under false promises, such as employment opportunities.”67 A “body part” is broadly defined in section 1 as any blood product, embryo, gamete, gonad, oocyte, zygote, organ or tissue as defined in the National Health Act 61 of 2003.

The definition of trafficking in persons for the removal of body parts must be distinguished from organ trafficking (trafficking in separated organs or body parts for profit). Organ trafficking is for example where an organ (or body part such as blood) is unlawfully taken from a laboratory or hospital and sold for profit.68 “Trafficking in organs and trafficking in persons for organ removal are different crimes, though frequently confused in public debate and among the legal and scientific communities. In the case of trafficking in organs (or body parts), the object of the crime is the organ (or body part), whereas, in the case of human trafficking for organ (or body part) removal, the object of the crime is the person. Trafficking in organs may have its origin in cases of human trafficking for organ removal, but organ trafficking will also frequently occur with no link to a case of human trafficking. The mixing up of these two phenomena could hinder efforts to combat both phenomena and provide comprehensive victim protection and assistance.”69

(g) the impregnation of a female person against her will for the purpose of selling her child when the child is born.

*Case law:

A conviction on human trafficking for this form of exploitation could not be traced yet in South African case law.

This form of exploitation is not defined in the PACOTIP Act. The argument that “fetus trafficking” should be recognised as a form of human trafficking70 and whether it may in certain circumstances overlap with this form of exploitation listed in (g) above, needs to be further explored and researched.

|

|

|

|

• trans-nationality or • the involvement of organised criminal groups in any of the trafficking offences. Therefore there can be liability for internal trafficking. 71 |

Section 4(2): Adoption and forced marriage for purposes of exploitation

*Case law:

A conviction on section 4(2) could not be traced yet in South African case law.

This section provides that a person who

(a) adopts (legally or illegally72) a child for the purpose of the exploitation of that child, or

(b) concludes a forced marriage with another person for the purpose of the exploitation of that person is guilty of “an offence”.73

Although the concept “forced marriage” is not defined in international law,74 the definition in section 1 clearly states that it is a marriage concluded without the consent of both parties to the marriage.

Interpretation challenges:

-

One interpretation is that a conviction of section 4(2) is a conviction on human trafficking.

-

However, the recommended interpretation is that section 4(2) creates two separate crimes that are not identical to human trafficking,75 but are associated therewith, because

-

two core elements of human trafficking, namely the prohibited conduct and the eans listed in section 4(1), are not required for the section 4(2) offences;

-

a person who contravenes section 4(2) is guilty of “an offence” and not of “ the offence of trafficking in persons”.

Sections 5 – 10: Offences associated with human trafficking

Several offences, besides the main offence of trafficking in persons, are usually committed during the trafficking process, including criminal activities to control victims by debt bondage or confiscation of travel documents, using the services of victims trafficked by others, facilitating trafficking and collusion between traffickers and carriers to transport victims. 76

Taken from: American Bar Association 2021:34

In the quest to combat trafficking efficiently the Act also criminalises conduct associated with human trafficking.

Section 5: Debt bondage

*Case law:

A conviction on section 4(2) could not be traced in South African case law.

Traffickers use multiple control methods to subjugate victims and thus ensure illegal profit from their victims. For example, perpetrators often coerce victims to enter into debt bondage, in terms of which they must pay off alleged debts through their labour. For this reason, the Act criminalises conduct that intentionally causes another person to enter into “debt bondage”,77 which is defined in section 1.78

Section 6: Possession, destruction, confiscation, concealment of or tampering

with documents

Iroanya79 posits that the confiscation “of travel documents of victims, especially of those who have travelled legally to trafficking destinations is further used to gain, maintain and perpetuate control over victims. The confiscation of victims’ travel documents also renders them illegal in transit or destination countries and as such vulnerable to exploitation. Their illegal status further prevents victims from accessing state protection”. The Act aims to combat this behaviour by criminalising the unlawful possession, destruction, confiscation, concealment or tampering with victims’ travel or certain other documentation.80

Section 7: Using services of victims of trafficking

Case law:

A conviction on this section is reported in South African case law.81

The Act further targets the demand for the services of trafficked persons by criminalising the conduct of:

-

end-users (clients) who create the market by intentionally using the services of trafficked persons;

-

those who supply the services of trafficked persons and intentionally benefits, financially or otherwise, from their services.82

Section 8: Conduct facilitating trafficking in persons

*Case law:

A conviction on this section has not been traced yet in South African case law.83

This broad offence is instituted to criminalise the conduct of several trafficking agents who play a part in the human trafficking process. The Act covers various criminal acts aimed at facilitating and promoting trafficking by advertising and distributing information in print or online,84 leasing or using buildings as well as financing, controlling or organising the commission of trafficking offences.85

Electronic communications service providers have no general obligation to monitor the data they transmit and store, but the Act requires that they must take reasonable steps to prevent the use of their service for hosting information that promotes trafficking.86 Service providers who detect such offenders must report their electronic communications identity numbers to the police, preserve any evidence for later prosecution and prevent further access to such electronic communications (internet address) by online customers. Service providers who fail to comply with these obligations are committing an offence.87

Section 9: Liability of carriers

*Case law:

A conviction on this section could not be traced yet in South African case law.

The Act targets the collusion between carriers and traffickers by providing that a “carrier”, which transports a passenger within or across the borders of South Africa, commits an offence if such carrier knows, or ought reasonably to know, that the passenger is a victim of trafficking.88 In addition, a carrier who knowingly transports a VoT in contravention of section 9(1), is liable to pay for the care, accommodation, transportation and repatriation or return of such VoT.89 In comparison to the term “commercial carrier” used in its counterpart in the Trafficking Protocol, the term ‘carrier” used in the Act is broader and includes both commercial and private carriers that provide transportation to promote human trafficking.90

Section 10: Involvement in offences under this Chapter

*Case law:

A conviction on this section of the PACOTIP Act could not be traced yet in South African case law.91

The Act criminalises conduct that constitutes the attempt to commit any offences created in the Act as well as the participation therein, and the incitement of others or the conspiring with others to commit such offences.92 The abovementioned criminalisation of the involvement in offences is largely a duplication since the provisions for the attempt, conspiracy and incitement in terms section 18 of the Riotous Assemblies Act 17 of 1956 apply to all statutory offences, including the PACOTIP Act.

Section 11: Liability of persons for offences under this Chapter

The lack of consent93 is not an express element of the definition of trafficking, but section 11 provides that it is no defence if

-

a trafficked child or a person having control over a child’s consents94 to the intended exploitation or the conduct element of any of the Chapter 2 offences, even if none of

the listed means was used by the perpetrator;95 or if the exploitation did not occur;96

-

a trafficked adult consents to the intended exploitation or the conduct element of any of the Chapter 2 offences, if any of the listed means were used by the perpetrator;97 or if the exploitation did not occur.

The Act further provides for the liability of an employer or principal for contravening sections 4 to 10.98

|

|

|

Section 12: Extra-territorial jurisdiction

“Human trafficking knows no boundaries and often transcends international borders. The successful combating of this crime, therefore, necessitates domestic legislation that empowers authorities to prosecute the offence even when it is committed in another country.”99 Therefore, the Act provides the courts with extra-territorial jurisdiction in certain circumstances where the crime was committed outside the borders of South Africa.100

“Persons that may be charged with such an offence include citizens or ordinary residents of the Republic, juristic persons or partnerships registered in the Republic, or other persons that have committed chapter 2 offences against a citizen or resident of the Republic. On conviction, the penalty is the same as is prescribed in chap 2 for that corresponding offence.”101

|

Group 4.3 covers sections 13 and 14 |

|

Section 13 Penalties Section 14 Factors to be considered in sentencing

Sections 13 and 14 on sentencing are covered by group 4.3.

14 Factors to be considered in sentencing If a person is convicted of any offence under this Chapter, the court that imposes the sentence must consider, but is not limited to, the following aggravating factors: (a) …; (b) …; (c) whether the convicted person caused the victim to become addicted to the use of a dependence-producing substance; 104 (d) …; (e) …; (f) …; (g) the physical and psychological effects the abuse had on the victim; 105 (h) whether the offence formed part of organised crime; 106 (i) whether the victim was a child; …107 (l) whether the victim had any physical disability, etc. 108 |

Group 4.3 covers sections 13 and 14

Section 13 Penalties

Section 14 Factors to be considered in sentencing

Sections 13 and 14 on sentencing are covered by group 4.3.

-

Relevant sources on this issue include:109

-

Relevant case law on section 14 includes: S v Obi 2020 JDR 0618 (GP) and other

cases 110

14 Factors to be considered in sentencing

If a person is convicted of any offence under this Chapter, the court that imposes the sentence must consider, but is not limited to, the following aggravating factors:

-

…;

-

…;

-

whether the convicted person caused the victim to become addicted to the use of a

dependence-producing substance;111

-

…;

-

…;

-

…;

-

the physical and psychological effects the abuse had on the victim;112

-

whether the offence formed part of organised crime;113

-

whether the victim was a child;114…

(l) whether the victim had any physical disability, etc.115

1 The concept is defined in the PACOTIP Act: s1.

*Application in case law: insert links to all the cases referred to in the text or footnotes into

the Case law column of Google drive workdocument

See the cases referred to in footnote 37 below.

Literature: insert links to all the literature referred to in the text/in footnotes into

column 3 (literature) of Google drive workdocument

UNODC. 2015. Issue paper – the concept of “exploitation” in the Trafficking in Persons Protocol.New York: United Nations.

2 The PACOTIP Act does not contain a definition of ‘exploitation’, but only provides list of some forms of exploitation – see discussion below (3.3.4 Legislative shortcomings and recommendations).

Literature

UNODC. 2015. Issue paper – The concept of ‘exploitation’ in the Trafficking in Persons Protocol. New York: United Nations.

3 Listed as a form of “exploitation” in PACOTIP Act: s 1.

4 See PACOTIP: s 4(2)(a).

Literature

UNODC. 2020. Issue paper – Interlinkages between Trafficking in Persons and Marriage. New York: United Nations.

5 Listed as a form of “exploitation” in PACOTIP Act: s 1.

6 Listed as a form of “exploitation” in PACOTIP Act: s 1.

7 Listed as a form of “exploitation” in PACOTIP Act: s 1.

8 Listed as a form of “exploitation” in PACOTIP Act: s 1.

9 UNODC. 2020b:28.

10 See the discussion in Mollema 2014:246-260.

11 Section 37 of the PACOTIP Act pertains to the the fourth P (partnerships/cooperation) by providing for international cooperation; Mollema 2014:260.

12 For an overview on the current status of the investigation, prosecution and adjudication of trafficking cases see US Department of State 2021:509-510.

13 Trafficking Protocol (art 3) read with the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (UNTOC Convention). See also the “International counter-trafficking framework ” discussed above. (by group 2).

14 This concept (TIP) is used interchangeably with ‘human trafficking’ in the literature on the topic.

Literature

UNODC. 2018. Issue paper – The International Legal Definition of Trafficking in Persons: Consolidation of research findings and reflection on issues raised. New York: United Nations.

15 See the discussion in Kruger 2016:73-78.

16 See the discussion in Kruger 2020: 761-763

17UNODC 2020b:29. “…obligations in relation to trafficking in children also arise from several other inter national instruments: Article 35 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child mandates that States Parties ‘take all appropriate national, bilateral and multilateral measures to prevent the abduction of, the sale of or traffic in children for any purpose or in any form.’ Under article 1 of the Optional Protocol to the Convention of the Rights of the Child on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography ‘States Parties shall prohibit the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography” as defined in article 2 of the Optional Protocol.” – UNODC. 2020b:40-41.

18 See the discussion in 3.3.4 Legislative shortcomings and recommendations below. See also Kruger 2016:78; Kruger 2020:761-763; American Bar Association 2021:18.

19 See the discussion in Mollema 2014:248-249; Kruger 2016:74-76.

20 UNODC 2020b:29.

21 UNODC 2020b:29.

22 Although some hold a different view, the sound interpretation of article 3(a) of the TIP Protocol as well as of section 4(1) of PACOTIP Act holds that ‘transportation’ is not a mandatory requirement for TIP - see the discussion in Kruger 2010:302-308.

23 UNODC 2020b:29. This point has been further emphasised: “... it is not an essential requirement of trafficking in persons that the victim has been physically moved by the traffickers.124 Placing too much emphasis on movement will result in cases being undetected as in many cases, at the time of movement or transportation, it can be difficult to determine whether the crime of human trafficking has been made out. Neither the victims themselves, nor border officials, may know the ultimate purpose for which they are being moved. It is often only at the place of destination, where persons are subjected to exploitation in its various forms, that trafficking can be easily made out.” – UNODC 2020b:45.

24 UNODC 2020b:29.

25 UNODC 2020b:30.

26 Mollema 2014:149; Kruger 2016:76-77.

27 UNODC 2020b:30; see the discussion on the purpose and variety of control methods used by traffickers in Van der Watt & Kruger 2019:936-943; Van der Watt & Kruger 2017:74, 79-80.

28 UNODC 2020b 29.

29 UNODC 2020b:30.

*Case law

In several cases the court recognised the following harm was caused to victims:

a) physical: Add link to S v Alina Dos Santos 2018 1 SACR 20 (GP): threats and assaults

. Add link to summary of the case: “SAF9 S v Dos Santos Nyehita” by Vanja’s team

b) psychological: Add links to S v Pillay case no. CCD 39/2019 (KZND) 24 Sentenced: 2020-12-11 (SAFLii); S v Obi 2020 JDR 0618 (GP) 7 – see Van der Watt 2020:72 ADD link to summary by Vanja team: “SAF2 S v Obi Nyehita..

30 UNODC 2020b:30.

31 Application in case law: Add links to

S v Seleso (orphaned girl child (16 yrs) from Lesotho, illegally in SA) - see Van der Watt 2020:72.

S v Mabuza 2018 2 SACR 54 (GP) (Mozambican girl children; illegally in SA)

S v Matini (girl with disability - mentally challenged) - see Van der Watt 2020: 71-71.

S v Pillay Case no. CCD39/2019 Durban High Court, KZN Sentenced 2021-3-23: (girl child)

Literature:

UNODC. 2015. Issue paper – the concept of “exploitation” in the Trafficking in Persons Protocol.

New York: United Nations.

32 Kruger, 2010:153; S v Alina Dos Santos 2018 1 SACR 20 (GP); S v Ugochukwu Eke Case no. SS14/2016 GJ (High Court Gauteng South: Johannesburg).

; .

33 UNODC 2020b:31-32.

34 In S v Ugochukwu Eke Case no. SS14/2016 GJ (High Court Gauteng South: Johannesburg) the complainant was forced to use drugs - Van der Watt 2020:71; S v Dos Santos 2018 1 SACR 20 (GP): Mozambican girl children, illegally in SA, threats and assaults, social and economic circumstances, addiction of dependence-producing substance (forced to smoke dagga).

35 S v Matini (girl with mental disability) -see Van der Watt 2020: 71-71.

36 According to the UNODC 2020b:32 children are inherently vulnerable due to their age and relative level of maturity. In Ntonga v State 2013 4 All SA 372 (ECG) par 2 & 29 the youngest complainant V, who was promised that accused no 1 will buy her shoes, was only 11 years old. Accused no1 procured V for accused no 2’s sexual gratification and he raped her.See also UNODC 2019:68-69.

37 S v Dos Santos 2018 1 SACR 20 (GP).

38 See the discussion in Snyman, C.R. 2020. Snyman’s Criminal Law. 7th ed. Cape Town: LexisNexis: 461-469.

39 UNODC 2020b:31.

40 Van der Watt 2020:72.

41 See Snyman 2020:351-354; 417-420.

42 UNODC 2020b:33.

43 See the discussion in Mollema 2014:249; Kruger 2016:76-77.

44 American Bar Association 2021:23-24.

45 PACOTIP Act: s 1-‘spouse, civil partner or life partner and dependant family members of a victim of trafficking’; Kruger 2016;77.

46 UNODC 2019:27; UNODC 2020b:30.

47 PACOTIP Act: s 4(1). For a further discussion see UNODC 2015b: 21-39; 104-125; Mollema 250.

48 UNODC 2020b:34.

49 Kruger 2016:67.

50 Cross reference This is confirmed in the PACOTIP act: s 11(1) discussed below.

51 See the discussion in Kruger 2020:768-771; UNODC 2020b:42.

52 Such as forced begging, the exploitation of criminal activities, namely “the exploitation of a person to commit, inter alia, pick-pocketing, shoplifting, drug trafficking and other similar activities which are subject to penalties and imply financial gain” - UNODC 2020b:42.

53 See also UNODC 2020b:42.

54 UNODC 2020b:34. For a further discussion see UNODC 2015b: 21-39; 104-125; Kruger 2020:768-771. See also the discussion in 3.3.4 Legislative shortcomings and recommendations below.

55 See the discussion in UNODC 2020b:37. For a further discussion see UNODC 2015b: 21-39; 104-125.

56 Cross-reference: Note that “debt bondage” is also introduced as a separate crime associated with human trafficking in section 5 of the Act.

57 See the discussion in UNODC 2020b:37-38.

58 Case law:

S v Nahimana Allima Case no. RC92/13 (Regional Court Nongoma, KZN) Judgment 2014-6-24.

S v Alina Dos Santos 2018 1 SACR 20 (GP)

S v Ugochukwu Eke Case no. SS14/2016 GJ (High Court Gauteng South: Johannesburg)

S v Fabiao Case no. 4SH/144/2016 (Regional Court Germiston) Judgment 2017-12-14.

S v Garhishe & Others Case no. RCW 74/17 (Regional Court Queenstown, EC)

S v Jezile 2016 2 SA 62 (WCC) ADD link to summary by Vanja team: “SAF3

S v Jezile Nyehita”

S v Knoetze & Another Case no. SCR 41/14 (Regional Court Stutterheim, EC)

S v Mabuza 2018 2 SACR 54 (GP) ADD link to summary by Vanja team: “SAF8

S v Mabuza Nyehita”

S v Matini & Another Case no. RC 123/2013 (Regional Court Uitenhage, EC) Judgement 2017-10-27

Ntonga v S 2013 4 All SA 372 (ECG)

S v Edozile Obi & Others 2020 JDR 0618 (GP) 1

S v Veeran Palan & Another Case no. RCD 13/14 Port Shepstone Reional Court (KZN) Judgment 2015-6-12; see also UNODC 2019:68.

S v Gordon Kelvin Raman Pillay Case no. CCD39/2019 Durban High Court, KZN

Sentenced 2021-3-23 SAFlii

S v Seleso & Another Case no. SS45/2018 (High Court Gauteng: Johannesburg) sentenced 2019

S v Zweni & Others Case no. 41/362/2012 (Regional Court Durban, KZN)

S v Onyekachi Eze Okechukwu Case no: 14/546/13 Pretoria Regional Court (child and adult victims).Van der Watt 2020:71 reports on the latter case: “In July 2019, the Pretoria Regional Court sentenced 39-year-old Nigerian national Onyekachi Eze Okechukwu to two life terms and an additional 39 years of imprisonment for the sex trafficking of two women in State vs Onyekachi Eze Okechukwu.12 Both women were rescued from a residential brothel in Pretoria in May 2013 (ANA Reporter, 2019). One of the victims had been a child when she was initially abducted from school by a Nigerian male – not arraigned in this trial – and kept at an unknown location where she was forced to smoke drugs. The sexual exploitation and abuse suffered by the victims were multi-layered. In studying the court records and transcripts in preparation for his testimony in the case, the author found that a much larger and loosely connected network of more than 20 Nigerian traffickers was involved and that the victims were moved between multiple addresses, were acquainted with multiple other potential trafficking victims and were ‘sold’ between multiple traffickers. One victim testified that the accused was “a small fish in a big pond” and highlighted that “there is more bigger Nigerians than him”. Both victims in the case had had experiences where members of the SAPS handed them back over to their exploiters after they had disclosed their abuse. This resulted in one victim, who at the time was 15 years of age, being forced to witness the physical dismemberment of her friend and the murder of two others, whilst the other victim stated that she lost “all faith and hope in their [police’s] ability to help her”. In his judgment, Magistrate Pravesh Singh stated that: “the entire evidence in this case unmasked the sordid and sleazy world of drug abuse, prostitution and exploitation.”

“Aldina Dos Santos, a 28-year-old Mozambican national, was sentenced to life imprisonment in April 2011 for the sex trafficking of three Mozambican children in State vs Aldina Dos Santos.7 The minor victims were exploited in a three-bedroom residential brothel in Moreleta Park, Pretoria. The victims were forced to smoke cannabis and have sexual intercourse with several sex-buying men daily. A photographer visited the brothel and took photographs of the victims scantily dressed and in the nude. The victims were informed that these photographs would be used to advertise them on the internet. The accused showed the victims pornographic videos and demonstrated to them by performing sexual intercourse on her boyfriend. In his dismissal of the appeal by the accused against life imprisonment, Judge Jacobs found that the complainants were “under constant threat, lived in fear, and were subjected to treatment that can only be described as inhumane”. The conviction on child trafficking in the magistrate court was confirmed on appeal in the High Court. In the case of State vs Nahimana Allima8, the 15-year-old victim was abducted in May 2012 on her way to a library in Ulundi by the accused, a 33-year-old female Burundi national, and two male accomplices. The victim was subsequently reported as missing by her family. The accused sexually exploited the child and gained financially from the victim’s rape and exploitation by multiple male sex buyers. The victim was located in Durban during September 2012, after which the accused was arrested. The accused was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment on 26 June 2014…In State vs Ugochukwu Eke10, a 15-year-old girl child was drugged and sexually exploited by a Nigerian trafficker. The victim was forced to take drugs and was exploited by as many as six sex-buying men per night during her ordeal in 2015. Judge Mabesele was quoted as asking “how many children’s lives has he ruined? Initially there were four girls who were found in that house, where have the three disappeared to?” (ANA Reporters, 2017a). Furthermore, Judge Mabesele was also quoted as stating that what “happened to her [victim] was cruel, inhumane and degrading” (ANA Reporters, 2017 2017.Ugochukwu Eke was sentenced to 20 years’ imprisonment by the Johannesburg High Court.” – Van der Watt 2020:71.

59 See the discussion in UNODC 2020b:34-35. For a further discussion see UNODC 2015b:21-39; 104-125.

60 “Servitude, a term that is also used in article 8 paragraph 2 of the International Covenant for Civil and Political Rights,81 generally includes egregious exploitation of one person over another that is in the nature of slavery but does not reach the very high threshold of slavery” - UNODC 2020b:37.

61 This component refers to “the free and informed consent of a worker to enter into an employment relationship and to the freedom to leave the employment at any time UNODC 2020b:36.

62 This definition of ‘forced labour’ is related to the definition of “forced or compulsory labour” in of the ILO Convention concerning Forced or Compulsory Labour of 1930 (article 2: par 1) to mean “all work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty, and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily” – see the discussion in UNODC 2020b:35-37. For a further discussion see UNODC 2015b:21-39; 104-125.

“129. The extraction of work or services “under the menace of any penalty” refers to a wide range of penalties used to compel someone to perform work or service, including penal sanctions and various forms of coercion such as physical violence, psychological threats or the non-payment of wages. The “penalty” may also consist of a loss of rights or privileges (such as a promotion, transfer, or access to new employment) or the threat of de portation - UNODC 2020b:36.

63 Case law

S v Judite Augusta Nyamtunbo Case number SH 45/18 Badplaas/Carolina, Mpumalanga

Sentence 18-7-2019.

S vs Nancy Eze Light Case no. GSH(2) 05/16 Goodwood Regional Court, Western Cape

Sentenced 2018-10-30

64 Literature:

UNODC. 2015a. Assessment toolkit - Trafficking in persons for the purpose of organ removal.New York: United Nations. See also Allain 2011:117-122: This article discusses a South African case of the illegal removal and transplanting for profit of kidneys in the case of S v Netcare Kwa-Zulu (Pty) Limited Agreement in Terms of Section 105A(1) of Act 51 of 1977, Netcare Kwa-Zulu (Proprietary) Limited and the State, Commercial Crime Court, Regional Court of Kwa-Zulu Natal, Durban, Case No. 41/1804/2010 sentenced on 11 November 2010. Although the facts of the case are in line with trafficking for the removal of organs/body parts, the offence was committed before the enforcement of the PACOTIP Act 7 of 2013 and thus the conviction was not on trafficking for the removal of body parts but in terms of other legislation.

Case law: Allain discusses the case of S v Netcare Kwa-Zulu (Pty) Limited Agreement in Terms of Section 105A(1) of Act 51 of 1977, Netcare Kwa-Zulu (Proprietary) Limited and the State, Commercial Crime Court, Regional Court of Kwa-Zulu Natal, Durban, Case No. 41/1804/2010 sentenced on 11 November 2010.

Background:

The PACOTIP Act 7 of 2013 was not in force yet and thus the Netcare hospital was convicted of other offences. Allain (2011:117) reports as fololows: “In November 2010, under the authority of the South African National Director of Public Prosecution, Netcare Kwa-Zulu (Pty) Limited entered into an agreement whereby it pleaded guilty to 102 counts related to charges stemming from having allowed its ‘employees and facilities to be used to conduct illegal kidney transplant operations’.2 Charged along with this private company which was, in fact, the St Augustine’s Hospital, located in Durban, South Africa, were the parent company, Netcare, its CEO, Richard Friedland, and eight others: four transplant doctors, a nephrologist, two transplant administrative coordinators, and a translator. The admission of guilt relates to 109 illegal kidney transplant operations which took place between June 2001 and November 2003 within a scheme whereby Israeli citizens in need of kidney transplants would be brought to South Africa for transplants performed at St Augustine’s Hospital.”

65 UNGIFT 2008:12.

66 UNODC 2020b:38. For a further discussion see UNODC 2015a:21-39; 104-125.

67 UNODC 2020b:38.

68 UNODC 2015a:17; UNODC 2020b:38. The trafficking in mere body parts is addressed through conventions such as 2014 Council of Europe Convention against Trafficking in Human Organs. INTERPOL 2021:7 states: “The Declaration of Istanbul on Organ Trafficking and Transplant Tourism states that organ trafficking consists of the act of buying and selling human organs, including any of the following activities9: (a) Removing organs from living or deceased donors without valid consent or authorisation or in exchange for financial gain or comparable advantage to the donor and/or a third person…”

69 UNODC 2015a:17. For a further discussion see UNODC 2015a:17-23; INTERPOL 2021:7.

70 Ha Le Thuy, Hoang Thi Hai Yen and Nguyen Quang Bao. 2021. Fetus trafficking in Viet Nam – The new criminal method of human trafficking. International Journal of Criminology and Sociology 10:1594-1603.

71 This is in compliance with the Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (UNTOC Convention): art 34.2; see also Kruger 2016:66; American Bar Association 2021:19.

72 See the discussion in UNODC 2020b:43 – “ The phrase “illegal adoptions” can be used to describe a situation where a child is sold to another person or where they are provided to another person with a view to the child being exploited. Such circumstances can fall within the meaning of exploitation in the Trafficking in Persons Protocol. It can also mean an adoption that is not done in accordance with applicable national laws; such cases will not necessa rily amount to exploitation. An Interpretative Note to article 3 subparagraph (a) explains that: “[w]here illegal adoption amounts to a practice similar to slavery as defined in article 1 paragraph (d) of the Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade, and Institutions and Practices Similar to Slavery it will also fall within the scope of the Protocol.”117 While the Supplementary Convention does not use the term “illegal adoption”, it considers “[a]ny institution or practice whereby a child or young person under the age of 18 years is delivered by either or both of his natural parents or by his guardian to another person, whether for reward or with a view to the exploitation of the child or young person or of his labour” to be a “practice similar to slavery”.

73 Kruger 2016:69.

74 UNODC 2020c:3-94; UNODC 2020b:42.

75 See the discussion in UNODC 2020b:42. “Some States Parties have opted to expressly include forced or servile marriage as a distinct element in their ant-trafficking laws and some have created separate offences targeting this conduct.”

76 Mollema 2014:251-254.

77 UNODC 2019:28. “The term ‘practices similar to slavery’ encompasses debt bondage, sale of children for exploitation, serfdom and servile forms of marriage, which have all been defined in international law. Definitions of these forms of exploitation are applicable to their use in the Trafficking in Persons Protocol. “ UNODC 2015b:8.

“Debt bondage: defined in the Supplementary Slavery Convention as: “the status or condition arising from a pledge by a debtor of his personal services or those of a person under his control as security for a debt, if the value of those services as reasonably assessed is not applied towards the liquidation of the debt or the length and nature of those services are not respectively limited and defined” (Article 1(a)). Unlike forced labour, the international legal definition makes no reference to the concept of voluntariness. It would appear, therefore, that international law does not envisage the possibility of an individual being able to consent to debt bondage. Debt bondage is said to be included within the prohibition on servitude contained in the ICCPR” UNODC 2015b:34. See also the discussion in UNODC 2015b:76..

78 'debt bondage' means the involuntary status or condition that arises from a pledge by a person of-

-

his or her personal services; or

-

the personal services of another person under his or her control, as security for a debt owed, or claimed to be owed, including any debt incurred or claimed to be incurred after the pledge is given, by that person if the-

(i) debt owed or claimed to be owed, as reasonably assessed, is manifestly excessive;

(ii) length and nature of those services are not respectively limited and defined; or

(iii) value of those services as reasonably assessed is not applied towards the liquidation of the debt or purported debt.

79 Iroanya 2014:106.

80 Kruger 2016: 70.

81 S v Obi 2020 JDR 0618 (GP):1. Van der Watt 2020:72 emphasised: “In State vs Edozile Obi & Others13, one adult female and two girl children between the ages of 13 and 14 were lured into a residential brothel in Springs, held hostage, forced to use drugs, raped and used as sex slaves. The girls were paid for their prostitution with drugs and hardly received food. The author conducted a pre-trial interview with the adult victim, who explained how she had been recruited at Club 26 in Springs, before being lured to the residence of the accused. She explained how she had tried to escape on multiple occasions and how SAPS officials frequented the brothel to receive payment from accused 1 and exploited the victims at the premises. Two of the victims had pictures of them in a half-naked state taken by one of the accused persons, after which the photographs were used to advertise the victims on a prominent adult entertainment website. Multiple sex-buying males responded to the online advertisements and sexually exploited the victims at the residential brothel. One of the victims was also caused to watch pornography by one of the accused persons, after which she was raped in the presence of another victim. Residents in the area reported that “the brothel was one of three on the busy street, which was also populated by law firms, mechanics, upholsterers, a day-care centre and an estate agency” (Springs brothel owner gets multiple life terms for human trafficking, 2019). Accused 1, a Nigerian national, was convicted and sentenced on 18 September 2019. He received 6 life sentences and an additional 129 years. His co-accused both received suspended sentences.”

Although other convictions on section 7 could not be traced in case law, several trafficking cases referred to “clients” that was part of the trafficking ring but these clients were not prosecuted and convicted. In December 2019, the Queenstown Regional Court in the Eastern Cape sentenced five accused for human trafficking and sexual exploitation after they abducted a 12-year-old girl in Whittlesea and used her as a sex slave for approximately a month in State vs Garhishe and others.14 Harun Mohammed, 38 years old, paid R100 to the four co-accused women, who, in turn, offered the 12-year-old girl to him for sexual exploitation. The sentences of Garhishe, Klaas, Kaziwa and Tom do not run concurrently and each will serve 24 years' direct imprisonment. Harun Mohammed was sentenced to life imprisonment for rape (Maphanga, 2019).” - Van der Watt 2020:72.

82 Mollema 2014:253; Kruger 2016:70.

83 Although a conviction on section 8 could not be traced in case law, several trafficking cases referred to the use of advertisements to facilitate or promote trafficking. In State vs Edozile Obi & Others, two of the victims “had pictures of them in a half-naked state taken by one of the accused persons, after which the photographs were used to advertise the victims on a prominent adult entertainment website. Multiple sex-buying males responded to the online advertisements and sexually exploited the victims at the residential brothel.” - Van der Watt 2020:72. In S v Seleso Gauteng South (Johannesburg) High Court case no: SS45/2018 (GJ) the accused “deceived and lured the 16-year-old victim to South Africa from Lesotho with promises of furthering her education during October 2015. The accused sexually exploited the victim for monetary reward and kept the proceeds. The victim was registered on Streamatemodels.com, a website found on the internet that facilitates the viewing of persons that perform various sex acts upon payment by clients. Both accused persons forced the victim to perform sex acts for the paying customers” -.Van der Watt 2020:72-73. In State vs Aldina Dos Santos the minor victims were “forced to smoke cannabis and have sexual intercourse with several sex-buying men daily. A photographer visited the brothel and took photographs of the victims scantily dressed and in the nude. The victims were informed that these photographs would be used to advertise them on the internet.” -Van der Watt 2020:71.

84 For example to facilitate human trafficking activities including child-sex tourism and webcam sex shows; Iroanya 2014:109.

85 Mollema 2014:53; Kruger 2016:71; UNODC 2019:28.

86 UNODC 2019:29.

87 Mollema 2014:253.

88 UNODC 2019:29.

89 Cross-reference to section 30(1)(c): court order for payment of compensation to the state’s Criminal Assets Recovery Account.

90 Kruger 2016:68-69.

91 However a conviction was secured under the SORMA Act in S v Samantha Haether Wiedermeyer & others Case no. 14/255/2015 Gauteng Regional Court Pretoria Sentenced 2018-8-27 for contravening section 71 (1) 2 (b) of SORMA Act 32 of 2007 (Involvement in Trafficking in persons for sexual purposes).

92 See the discussion in Kruger 2016:67-68; Mollema 2014:253; UNODC 2020b:45.

93 Literature

UNODC. 2014. Issue paper – The role of ‘consent’ in the Trafficking in Persons Protocol. New York: United Nations.

94 Iroanya 2014:109.

95 Kruger 2016:78-80.

96 Case law:

S v Fabiao Case no. 4SH/144/2016 (Regional Court Germiston) Judgment 2017-12-14. Arrangement made to force Zimbabwean girl (12 yrs) to marry accused, but arrested before marriage

97 Kruger 2016:78-80.

98 Section 11(2)-(4).

99 Kruger 2017:258.

100 See the discussion by Iroanya 2014:111.

101 Kruger 2017:258; see also Mollema 2014:254.

102 Kruger 2020: 64-767; Kruger 2016:80-82; Van der Watt 2020: 71-73; Iroanya R O. 2014. Human trafficking with specific reference to South African and Mozambican countertraffickinglegislation. Acta Criminologica 27(2):102-115; Mollema N & Terblance SS. 2017. The effectiveness of sentencing as a measure to combat human trafficking. South African Journal on Criminal Justice, 30:198-223.

103 S v Obi 2020 JDR 0618 (GP): 4-7. ADD link to summary by Vanja team: “SAF2 S v Obi Nyehita

104 S v Dos Santos 2018 1 SACR 20 (GP) 27; S v Obi 2020 JDR 0618 (GP).

105 S v Pillay case no. CCD 39/2019 (KZND) 24 Sentenced: 2020-12-11 (SAFLii); S v Obi 2020 JDR 0618 (GP).

106 S v Dos Santos 2018 1 SACR 20 (GP) 27.

ADD link to summary by Vanja team: “SAF9 S v Dos Santos Nyehita”

107 S v Obi 2020 JDR 0618 (GP).

108 S v Matini & Another Case no. RC 123/2013 (Regional Court Uitenhage, EC) Judgement 2017-10-27; Van der Watt 2020:71-72 reports: “In October 2017 Nombuyiselo Matini and Nolubabalo Mboya were convicted in State vs Matini and another11 for a wide range of offences, including racketeering, keeping a brothel, the trafficking of four adult and two mentally disabled victims for sexual exploitation, the commercial sexual exploitation of a child, living off the earnings of prostitution and the sexual exploitation of mentally disabled victims. “The case dates back to July 2012 when two mentally challenged girls were abducted from Kwanobhule area and taken to Fairview Race Course, where they were held captive” (Life sentence for human trafficker, 2018). The victims, who came from impoverished communities, had been reported missing at KwaNobhule police station by their parents. The victims were trafficked and forced into prostitution at a brothel, which had been in operation since 2006 in Fairview, Port Elizabeth. In February 2018, Matini received six life sentences and 36 years and Mboya received a suspended sentence and correctional supervision (Koen, 2019; African News Agency, 2017).”

109 Kruger 2020: 64-767; Kruger 2016:80-82; Van der Watt 2020: 71-73; Iroanya R O. 2014. Human trafficking with specific reference to South African and Mozambican countertraffickinglegislation. Acta Criminologica 27(2):102-115; Mollema N & Terblance SS. 2017. The effectiveness of sentencing as a measure to combat human trafficking. South African Journal on Criminal Justice, 30:198-223.

110 S v Obi 2020 JDR 0618 (GP): 4-7. ADD link to summary by Vanja team: “SAF2 S v Obi Nyehita

111 S v Dos Santos 2018 1 SACR 20 (GP) 27; S v Obi 2020 JDR 0618 (GP).

112 S v Pillay case no. CCD 39/2019 (KZND) 24 Sentenced: 2020-12-11 (SAFLii); S v Obi 2020 JDR 0618 (GP).

113 S v Dos Santos 2018 1 SACR 20 (GP) 27.

ADD link to summary by Vanja team: “SAF9 S v Dos Santos Nyehita”

114 S v Obi 2020 JDR 0618 (GP).

115 S v Matini & Another Case no. RC 123/2013 (Regional Court Uitenhage, EC) Judgement 2017-10-27; Van der Watt 2020:71-72 reports: “In October 2017 Nombuyiselo Matini and Nolubabalo Mboya were convicted in State vs Matini and another11 for a wide range of offences, including racketeering, keeping a brothel, the trafficking of four adult and two mentally disabled victims for sexual exploitation, the commercial sexual exploitation of a child, living off the earnings of prostitution and the sexual exploitation of mentally disabled victims. “The case dates back to July 2012 when two mentally challenged girls were abducted from Kwanobhule area and taken to Fairview Race Course, where they were held captive” (Life sentence for human trafficker, 2018). The victims, who came from impoverished communities, had been reported missing at KwaNobhule police station by their parents. The victims were trafficked and forced into prostitution at a brothel, which had been in operation since 2006 in Fairview, Port Elizabeth. In February 2018, Matini received six life sentences and 36 years and Mboya received a suspended sentence and correctional supervision (Koen, 2019; African News Agency, 2017).”