IN THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEAL

OF SOUTH AFRICA

CASE NO: 113/03

In the matter between :

ROAD ACCIDENT FUND Appellant

and

DAVID VOGEL Respondent

___________________________________________________________________________

Coram: MARAIS JA, JONES et VAN HEERDEN AJJA

Heard: 23 February 2004

Delivered: 11 March 2004

Mobile ground power unit providing electric power to stationary aircraft at airports –

not a motor vehicle as defined in s 1 of Road Accident Fund Act 56 of 1996.

__________________________________________________________________________

J U D G M E N T

___________________________________________________________________________

MARAIS JA/

MARAIS JA:

[1] This appeal raises again the question whether a particular item is a motor vehicle as defined in s 1 of the Road Accident Fund Act 56 of 1996 (‘the Act’). The item is a mobile Hobart ground power unit (‘the unit’). After agreeing to consider separately in terms of Rule 33(4) certain issues, and after hearing evidence and argument, the Court a quo made orders declaring, first, that the unit is a motor vehicle in terms of s 1 of the Act, and secondly, that the collision in which it was involved was caused by the sole and exclusive negligence of one Botes. Leave to appeal against both orders was refused by the Court a quo (Daniels J) but leave to appeal against only the first of the declaratory orders was granted by this Court.

[2] Section 1 of the Act provides that –

‘“Motor vehicle” means any vehicle designed or adapted for propulsion or haulage on a road by means of fuel, gas or electricity, including a trailer, a caravan, an agricultural or any other implement designed or adapted to be drawn by such motor vehicle.’

[3] The interpretation to be given to this definition has been laid down in a number of cases heard by this Court. These propositions can be extracted from them. First, the road referred to in the definition is not just any kind of road however restricted public access, whether vehicular or on foot, may be, but a road which the public at large and other vehicles are entitled to use and do use; in general parlance, a public road.1

[4] Secondly, the mere fact that the item is capable of being driven on a public road is not per se sufficient to bring it within the definition.2

[5] The word ‘designed’ in its context means that the enquiry is what ‘the ordinary, everyday and general purpose for which the [item] in question was conceived and constructed and how the reasonable person would see its ordinary, and not some fanciful, use on a road’.3 The appropriate test is whether a general use on public roads is contemplated.4

[6] If, objectively regarded, the use of the item on a public road would be more than ordinarily difficult and inherently potentially hazardous to its operator and other users of the road, it cannot be said to be a motor vehicle within the meaning of the definition.5 (I infer that this is because it then cannot reasonably be said to have been designed for ordinary and general use on public roads.)

[7] I should add that I do not read the previous judgments of this court as laying down that unless the item in question can be characterised as in para [6] it must be regarded as satisfying the requirements of the definition of motor vehicle. I understand this characterisation to be merely one of many conceivable indications that an item was not designed for general use on public roads. The use of a particular item on a public road may not be inherently difficult or dangerous but it may still not qualify as a vehicle designed for the purposes set out in the definition of s 1 of the Act.

[8] That an item may have been designed primarily for a purpose not covered by the definition of motor vehicle in the Act does not necessarily disqualify it from being regarded as a motor vehicle as defined. If it was also designed to enable it to be used on public roads in the usual manner in which motor vehicles are used and if it can be so used without the attendant difficulties and hazards referred to in para [6], it would qualify as a motor vehicle as defined. In short, such latter use need not be the only or even the primary use for which it was designed.6

[9] I must, with respect, confess to being unconvinced about the soundness of the suggestion in this Court’s judgment in Chauke that the words ‘designed for’ have a less subjective connotation than the words ‘intended for’. The equating of the words ‘intended for’ with words such as ‘reasonably suitable for’ or ‘reasonably apt for’ by Salmon J in Daley and Others v Hargreaves7 seems to me, again with respect, to be unfounded when viewed purely as a matter of the correct use of language. ‘Intended for’, to my mind, plainly conveys the subjective intention of a human agency; ‘suitable for’ or ‘apt for’, on the other hand, is a purely objective criterion which has nothing to do with the subjective intention of the manufacturer of the article under consideration, save to the extent that it may provide evidence of that intention in cases in which it has not been clearly expressed. The statutory context in which words such as ‘intended for’ or ‘designed for’ are used may of course show that, unhappy or inappropriate though the legislature’s choice of words may have been, they must be taken to mean something different from what, divorced from their context, they would mean.

[10] Indeed, when Olivier JA ultimately formulated his own interpretation8 of what the word ‘designed’, in the context of the Act, conveyed, he posited both a subjective and an objective test. To say that the word ‘conveys the ordinary, everyday and general purpose for which the vehicle was conceived and constructed’ (my emphasis) is to postulate a subjective test. To add ‘and how the reasonable person would see its ordinary, and not some fanciful, use on a road’ postulates an objective test.

[11] The irreconcilability of the two concepts is, I think, more apparent than real. Various possibilities can arise. The manufacturer of the item under consideration may not have designed it to be used generally on ordinary public roads at all; yet it may, objectively regarded, be eminently suitable for that purpose. If so, it seems unlikely that parliament would not have wanted to provide the public with a remedy against the Road Accident Fund if it was negligently so used and caused injury. At the other end of the spectrum, and probably extremely unlikely to occur in practice, is an item which was designed by the manufacturer for general use on ordinary roads, but which an objective appraisal of its suitability for that purpose shows that the manufacturer has failed to achieve the result intended. If such a unit is negligently operated on a road and injures a third party, it seems equally unlikely that parliament would have wanted the third party to have recourse against the Road Accident Fund.

[12] The net result, so it seems to me, is that while the legislature has not entirely ignored the subjective intention of the designer, it is not per se conclusive and the item’s objective suitability for use in the manner contemplated by s 1 is to be the ultimate touchstone. Whatever reservations I may have about some of the reasoning of Olivier JA, they do not detract from the soundness of the test which he ultimately articulated.

[13] I turn to the application of these considerations to the unit. It is called by its manufacturer the Hobart Ground Power unit. According to the manufacturer’s promotional brochure it manufactures ‘welding systems, aircraft ground power equipment and industrial battery chargers’. Its Motor Generator Division is ‘the world’s largest producer of commercial aircraft ground power equipment, providing 80 to 90% of all commercial airline requirements’. In 1969 it ‘(a)nnounced first ground power equipment for servicing first of the jumbo jets, the Boeing 747’ and described it as ‘(a) ground power unit (which) supplies electricity to the plane while it is on the ground’.

[14] The parts catalogue issued by the manufacturer (Cummins) of the diesel engine which provides the means of propulsion of the unit lists in separate columns in the case of each component part the field of application of the engine. The columns are headed ‘automotive’, ‘off-highway’, ‘construction and industrial’ and ‘industrial power’. There are 35 pages which bear these column headings. An ‘x’ has been used to indicate what the field of application of the relevant parts listed on the page is. On 24 out of 35 pages an ‘x’ has been placed next to the heading ‘off-highway’. It was argued by counsel for the appellant that this was significant and showed that use on a highway was not intended. I shall return to that submission in due course.

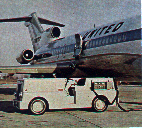

[15] Photographs of the unit in its original designed state9 show it to be a large and lengthy box-like metal structure on four pneumatic tyres. In virtually the middle of the left side of the structure provision is made to seat the operator of the unit in such a manner that he or she is seated on the left hand side of the structure facing forwards in the direction in which the unit would move if it were to travel anywhere. There is no enclosed cabin for the operator; he or she is exposed to the elements of nature.

[16] The unit is equipped with a four cylinder diesel engine and a three speed gear box with a reverse gear. It has a conventional rack and pinion steering mechanism and a conventional steering wheel, the shaft of which is almost vertical. There are left and right turning indicators at both the front and the back of the unit. There are also broad yellow and black striped chevrons which extend over the full width of the unit at both the front and back.

[17] Its lighting system comprises two headlights which may be dimmed or brightened, reflectors at the front, rear and sides of the unit, and brake lights. In its original designed state it had no windscreen but for use in South Africa a cab with a windscreen, side windows, and window wiper was fitted.10 It is not entirely clear whether this was done by the manufacturer at the purchaser’s request or by the purchaser itself after delivery of the unit. The top speed of the unit was between 40-60 kph. The operator’s view in the unit’s originally designed state was unobstructed. The addition of the cab resulted in minor impairment of the view on the right hand side of the unit.

[18] It has no speedometer and no safety belt. It has a hooter. Its turning arc is restricted but comparable to that of a motor vehicle of equivalent size. It is said to steer and handle like a Land Rover. It was not equipped with rear and side view mirrors in its original designed state but in South Africa the standard procedure was to have them fitted to the unit. As it happened, this particular unit no longer had its mirrors at the time of the incident giving rise to the litigation but nothing turns on that.

[19] There is no provision for the conveyance of passengers or anything else but it is fitted with a tow bar. Its ground clearance is 300mm which is comparable to that of a light delivery vehicle. It has no tendency to oversteer or understeer and its weight is evenly distributed.

[20] The location of the gear lever is unlike that which is ordinarily found in motor vehicles designed for general use on public roads. It is situated between the driver’s legs.

[21] The Court a quo concluded that the primary function or purpose for which the unit was designed was to supply power to stationary aircraft at airports. Indeed, the learned judge aptly described it as ‘a mobile power plant’. Although he did not say so in terms, it appears that he considered general use on a road of the kind envisaged in the definition to have been either an integral component of the primary design objective or at least a secondary design objective in the sense contemplated in the previous decisions of this Court. In my view, he erred.

[22] The basic approach of the Court a quo was that the unit had to be capable of self-propulsion if it was to serve its principal purpose. Moreover, it would have to be capable of being driven along the roads customarily to be found on airport aprons with relative safety to its operator and to other users of the roads. Daniels J concluded that the unit was ‘as a probability’ so designed. It is not clear whether he also thought it to have been designed to be capable of being driven on public roads other than the roads to be found at airports in similar safety.

[23] The argument that the ‘off-highway’ designations in the parts catalogue referred to in para [14] above show that the unit was not designed for use on a highway is, to my mind, unsound. First, this is not the designation of the manufacturer of the unit; it is that of the manufacturer of the diesel engine which powers the unit and relates solely to the engine and its parts. Secondly, there is no reason to believe that the designations are intended to tell a purchaser of the engine or spare part what it may not be used for; they are intended to convey the manifold uses to which the engine and its parts may be put. Automotive is one of them.

[24] It seems to me to be abundantly clear that this unit was not designed by its manufacturer for propulsion or haulage on a road of the kind envisaged by the definition in s 1 of the Act. Its ungainly proportions and appearance; the absence of provision for conveying anything other than its operator and (if it can be regarded as conveyance, which I doubt) the power unit which is an integral part of it; the absence of a speedometer, windscreen, mirrors, safety belt, or protection against the elements for the operator; the inconvenient and unconventional location of its gear lever; the low speeds of which it is capable and, above all, its sole raison d’etre, namely, the provision of electrical power to stationary aircraft at airports, make it impossible to conclude that it was designed for general use on public roads other than those which would be encountered within the operational area of airports.

[25] The existence of some features which are common to motor vehicles properly so called takes the matter no further. They were obviously required if the unit was to fulfil its function as a mobile power plant and be able to traverse terrain upon which people, aircraft, equipment and vehicles would be encountered. It does not follow that they were provided to enable the unit to be used on public roads other than the roads to be found within the operational area of airports.

[26] The additions to the unit which were made or commissioned by its owner cannot alter the fact that the maker of the unit did not design it for propulsion or haulage on a road of the kind contemplated by the definition. Nor can it be said to have been ‘adapted’ for that purpose. Those additions were obviously to protect the operator from the elements. As soon as a cab was fitted the partial impediments to rearward visibility which it would create rendered it desirable that side view mirrors be fitted. These limited adaptations to the original design of the unit can hardly be regarded as sufficient to convert a unit which was not designed for the purposes set forth in the definition in s 1 into one which, by virtue of the adaptation, is thenceforth to be regarded as having been successfully adapted for such purposes.

[27] The fact that this unit was in fact driven on a few occasions from one airport to another along public roads proves no more than that it was possible to use its automotive power to travel relatively long distances but such use of the unit was not, in my opinion, ‘the ordinary, everyday and general purpose for which the [unit] was conceived and constructed’ [or adapted], or a use which the reasonable person would see as ‘ordinary and not fanciful’.

[28] Not only is this a case in which the manufacturer did not subjectively design the unit for the purposes set forth in s 1; it is a case where, even if it had purported to do so, the application of the objective test of whether the unit, objectively regarded, was reasonably suitable for such purposes would have caused it to fail in its attempt.

[29] In the event of the appeal succeeding, counsel for the appellant asked for the costs of two counsel. There is, in my opinion, not sufficient justification for such an order. The principles applicable to a determination of the issue have been settled in previous decisions of this Court. The factual enquiry involved was neither lengthy nor complex.

[30] The appeal is upheld with costs. The order of the Court a quo dismissing the special plea is set aside and substituted by an order upholding the special plea and dismissing the plaintiff’s claim with costs.

_____________________

R M MARAIS

JUDGE OF APPEAL

JONES AJA )

VAN HEERDEN AJA ) CONCUR

“A”

“B”

1Chauke v Santam Ltd 1997 (1) SA 178 (A) at 181F-G.

2Matsiba v Santam Versekeringsmaatskappy Bpk 1997 (4) SA 832 (SCA) at 834H; Chauke at 182J - 183A.

3Chauke at 183B-C.

4Chauke at 184B.

5Chauke at 183C.

6Mutual and Federal Insurance Co Ltd v Day 2001 (3) SA 775 (SCA) para [14].

7 [1961] All ER 552 (QB).

8Chauke at 183B.

9A photograph marked “A” is annexed to this judgment.

10A photograph marked “B” is annexed to this judgment.